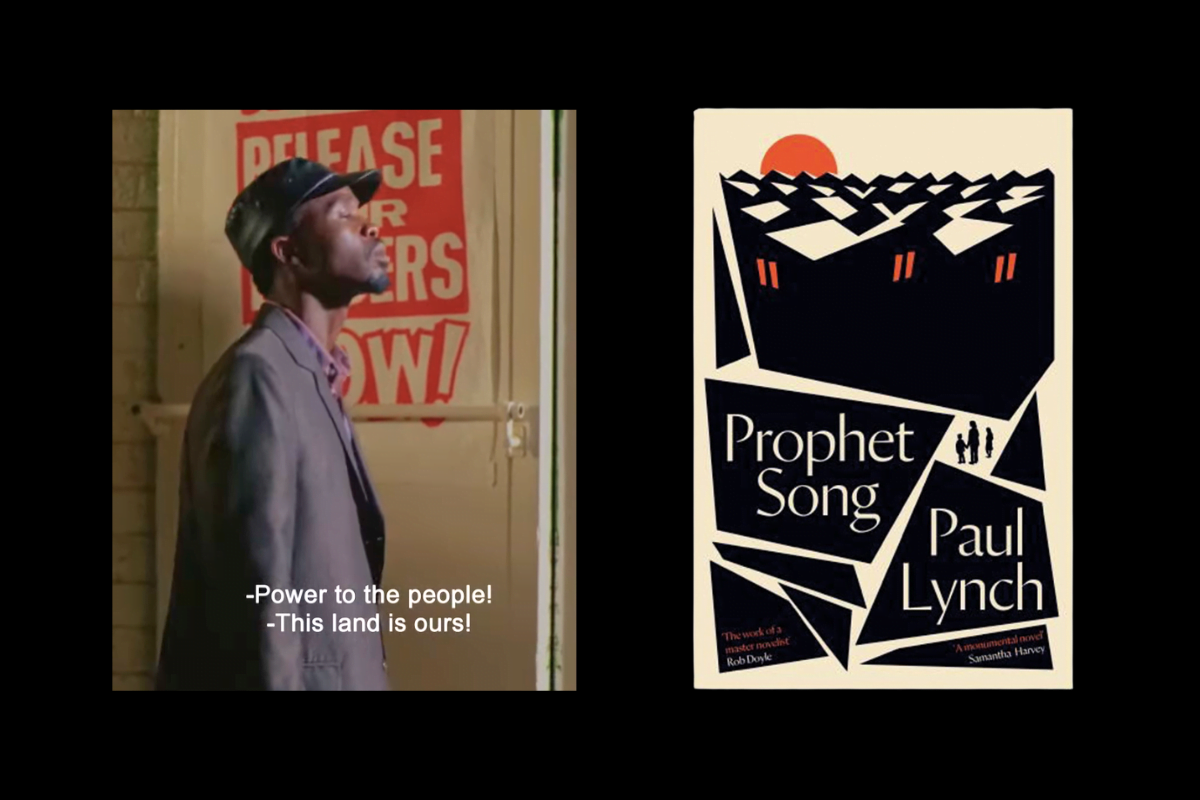

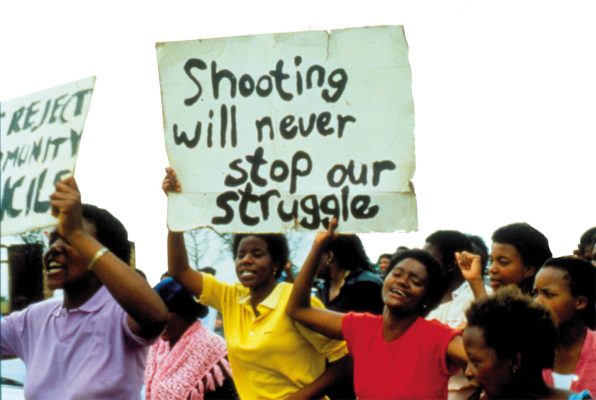

Mapantsula: A gripping portrayal of the anti-Apartheid struggle

Originally released in 1988, Mapantsula recently made a triumphant return to UK cinemas to mark the 30th anniversary of South Africa’s first democratic elections.

Mapantsula made waves wherever it screened, finding fertile ground in an international climate that was turning against Apartheid.

Writer and actor Thomas Magotlane’s audacious journey to bring the film to London, outsmarting South African censors with fake scripts, is a story in itself.

At the heart of Mapantsula is Panic (played by Magotlane): a small-time crook, whose bleak worldview undergoes a seismic shift through a series of gripping events.

The film masterfully explores how the class struggle serves to transform consciousness.

The movie’s portrayal of the relentless oppression suffered by black communities is gut-wrenchingly authentic. It exposes the Apartheid state’s ruthless tactics of intimidation, abduction, and even murder against those who dared to resist.

Mapantsula is a testament to the indomitable spirit of the oppressed black masses. Particularly powerful are the jail scenes, where UDF (United Democratic Front) comrades-in-arms chant in solidarity whilst on hunger strike.

Both a narrative and a product of the fight against Apartheid, Mapantsula is a must-see for anyone seeking to understand this pivotal chapter in history.

Wade Tucker, Liverpool

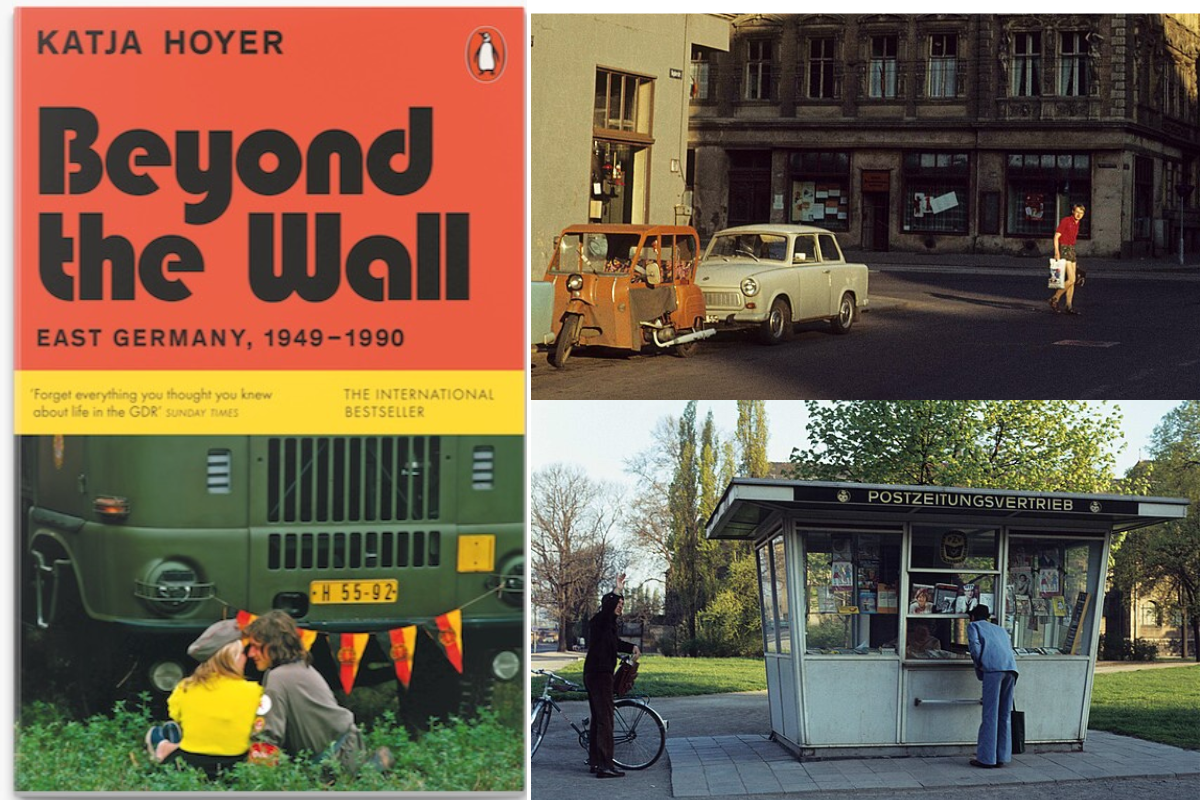

Prophet Song: A dystopian novel that resonates today

The ‘golden age’ of dystopian fiction was thought to have long-since passed.

Stalinist and Cold War-era classics like 1984 and Fahrenheit 451 resonated with a set of readers who had few illusions in free speech and dreaded a nuclear end to the world.

But as the crisis of capitalism once again threatens us with war, economic collapse, and climate catastrophe, we are seeing a revival of this genre.

This is happening both through adaptations of books like The Hunger Games and Handmaid’s Tale, and with a new generation of novelists who understand that dystopian fiction is not restricted to sci-fi or fantasy.

Prophet Song – Paul Lynch’s bestselling novel and the deserving winner of 2023’s Booker Prize – marks a continuation of this process.

The book follows Eilish, whose trade-unionist husband disappears whilst organising a demonstration against the newly-elected National Alliance party.

The novel is intentionally close to home. Written entirely in the present tense, short sentences, wandering metaphors, and the protagonist’s confused internal dialogue thrust the reader into a slow-burn panic attack of a plotline, which leaves us anxious and lacking closure.

At first she tries to go through the courts, then international human-rights organisations, fruitlessly trying to retrieve her husband and keep the rest of her family together.

Eilish spirals as she witnesses Ireland descending slowly into a police-state, and civil war, while neighbours turn against her and the state does everything it can to punish her family.

The novel doesn’t try to give a complete political explanation of the rise of the National Alliance. It lets readers fill in the gaps between Eilish’s often contradictory impressions. But through this it reveals plenty.

When all the rights that Eilish thinks are inalienable – the right to a solicitor, a fair trial, freedom of assembly, freedom of speech, the right to strike, are taken away – it is proven exactly how much of a thin veneer these were in the first place.

All the old platitudes, repeated throughout the book, become empty words. Even as Eilish continues to recite these to her daughters (“first there are stern warnings, and then there are sanctions, and when the sanctions don’t bite they bring everyone around the table”), she cannot meet their eyes.

Prophet Song is peppered with unflinching references to reality. Protestors are taken to an arena by state forces and don’t return; school-age boys are arrested and their bodies found, beaten and tortured, weeks later.

Lynch was directly inspired by the Syrian civil war. But its bestseller status must at least partially have come from the way it resonates with the destruction in Gaza.

It is refreshing to see dystopian fiction which for once does not try to cloak itself in semi-fantastical elements.

Laurie O’Connel, London