Following the bizarre Napoleon (2023), British director Ridley Scott has produced a film that is sure to captivate those who spend their time pondering the Roman Empire.

At first glance, this may seem like little more than a modern redux of Gladiator; a cynical, calculated attempt to recapture the critical acclaim of his earlier success. After all, Scott’s original foray into the Colosseum earned him five Oscars, including Best Picture.

With a soundtrack that feels heavily ‘inspired’ by Hans Zimmer’s work, and a narrative echoing many familiar beats, the film revisits the era following the end of the Pax Romana – though heavily fictionalised.

At the same time, there are solid reasons for this rehash.

The plot continues the political intrigue of the original, making it a fitting sequel. It retains the scheming, drama, and epic battles that made Gladiator so beloved. And while some action scenes stretch the limits of plausibility, a blend of CGI and practical effects breathes life into Scott’s more ambitious and eccentric visions.

Warning: This review contains spoilers

‘A kingdom of iron and rust’

The first film focuses on the power struggle between Emperor Commodus, the narcissistic son of Marcus Aurelius with gladiatorial ambitions, and Maximus, a revered general and the former emperor’s chosen successor, who becomes a hunted man and a slave.

Their conflict culminates in a fight to the death in the Roman Colosseum – marking the end of both men’s lives, and the beginning of decades of turmoil.

Historically, this was a period of instability, with five emperors rising and falling in just five years, ushering in the tumultuous Severan dynasty. Rome, in the words of one scholar, was transformed “from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust”.

Through a twist of fate, we learn that Maximus had a secret son, Lucius, born from an affair with Marcus Aurelius’ daughter.

Fast forward twenty years, and we meet Lucius (played by Paul Mescal), now living under the alias Hanno and defending Numidia – “the last free city in North Africa” – from invasion by the Roman army.

This attack, led by General Marcus Acacius (Pedro Pascal), results in the death of Hanno’s wife, Arishat, during the battle.

Arishat’s death ostensibly becomes the catalyst for Hanno’s rage against the Empire; a rage that propels him toward gladiatorial success – the only path to freedom for slaves.

This mirrors the events of the first film, in a clear homage.

While the story rhymes with the original, however, this sequel falls short in execution.

Having witnessed his father’s death at the hands of his uncle, and now enduring the loss of his wife, one might expect Lucius’ fury to carry greater emotional weight. But the film, despite Mescal’s commendable performance, falters in establishing the depth of his relationship with Arishat or his connection to his adoptive homeland.

Her death occurs so early in the story that it feels rushed and underdeveloped. Furthermore, the revelation of Lucius as Maximus’ son is not immediately evident, making his motivations feel hollow.

This stands in stark contrast to the first Gladiator, where Maximus Decimus Meridius, weary from years of military campaigns, longs to return to his family in Spain. His devastating loss – the murder of his wife and son at the hands of the Praetorian Guard – hits with unparalleled emotional resonance, firmly grounding his quest for vengeance.

Bread and circuses

After being captured during the battle and enslaved, alongside numerous other prisoners of war, Lucius’ journey to Rome is marked by a series of harrowing events.

Among them is a brutal encounter in the arena with vicious killer baboons, which he survives through sheer skill and determination.

Ultimately, he is trafficked to Rome by Macrinus, a former slave turned cynical political manipulator, who harbours deep resentment toward the Senate, and who attempts to use Lucius as an “instrument” in his schemes.

Denzel Washington’s delightfully sinister portrayal of Macrinus and Fred Hechinger’s turn as the tyrannical Emperor Caracalla are standout performances in the film.

Under the rule of Caracalla and his brother Geta, Rome has descended into chaos. The city’s streets are lined with starving, disease-ridden masses begging for scraps of bread.

Despite his celebrated military status, Rome’s most decorated general has grown disillusioned and longs to retire. He is particularly outraged by the emperors’ plans for further conquests in Persia and India, exclaiming: “The people of Rome need feeding!”

While the Roman masses are initially dazzled by the elaborate spectacles in the Colosseum, including grand recreations of epic naval battles, the excitement quickly fades.

The proletariat – the landless freemen of the Empire – grow restless, as the twin emperors’ extravagant distractions fail to mask Rome’s deepening crisis.

Tensions rise as the people’s anger begins to boil over. Discontent also brews among the ruling class, meanwhile, with figures like General Acacius and Lucilla conspiring to overthrow Caracalla and Geta. However, the execution of the widely beloved Acacius only further inflames public outrage, sparking widespread unrest.

As power slips from their grasp, the twin emperors find themselves besieged by the enraged masses, who encircle the palace in a final act of rebellion.

This political degeneration and collapse are epitomised by the interpersonal conflict between Caracalla and Geta. Their escalating bloodlust, both in the Colosseum and beyond, mirrors the Empire’s own decline.

Caracalla’s descent into madness – culminating in his absurd decision to appoint his pet monkey as first consul – serves as a grotesque reflection of Rome’s unravelling.

‘Dream of Rome’

Through a reunion with his mother, Lucilla, Lucius learns of his destiny: to realise the “Dream of Rome”.

This vision entails a Rome where the people are free from tyranny; where liberty is restored, and power is held by the Senate rather than by emperors.

Seizing the leadership vacuum left by the deranged emperors and the ineffectual Senate, Macrinus plans to consolidate power through brute force – a depiction that aligns closely with historical political struggles in the Roman Empire.

Lucius, however, believes this represents only one element in the equation. He resolves to fulfil Marcus Aurelius’ dream of restoring the Senate’s authority and ending imperial rule – aiming to unite a coalition of Rome’s diverse social classes to achieve this goal.

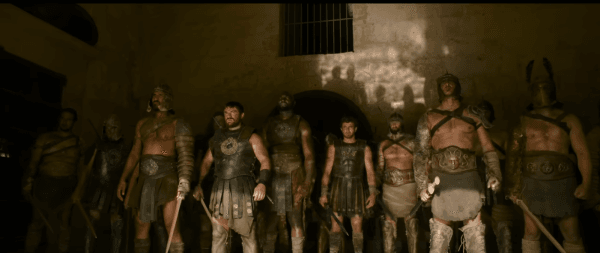

The film’s final act begins with Lucius delivering an impassioned speech to the enslaved gladiators of the Colosseum. He implores them to fight not just for survival in the arena, but for a higher ideal: freedom from bondage and the creation of a better future.

This call to action ignites their determination to resist the imperial forces.

Despite an initial surge of support, Lucius is forced to seek alliances beyond the arena, appealing to the military cliques of the Roman army and the Praetorian Guard to unite in pursuit of the “Dream of Rome”.

Unlike the first Gladiator film, the sequel’s ending leans toward optimism. The narrative suggests that true reward is not found in resignation or awaiting death, but in the ongoing struggle for a better future.

While Ridley Scott refrains from drawing overt parallels to today, the film effectively portrays a broader theme: that crisis-ridden systems – whether ancient or modern – inevitably face crises at the top, political opportunists (good or bad), and popular uprisings.

Bonaparte, not Spartacus

The sequel takes great pains to echo the mantra of the original film: “What we do in life echoes in eternity.”

Under the right conditions, it is true, certain individuals and historical figures – representing the aspirations and interests of certain classes – can bring about sweeping social change.

Historically, however, despite the desires of some influential figures, the Republic was not restored. Instead, this period was followed by a period of anarchy known as the ‘Crisis of the Third Century’.

The downfall of the Roman Empire, a system designed to protect the property and privileges of the great slave-owning class, could only have been achieved through a united revolution of the oppressed classes. Their failure to mount such a challenge ensured the Empire’s protracted decline.

By contrast, Lucius, despite his noble ideals and early reliance on a coalition of slaves and popular uprisings within the city, ultimately derives his power from the military, the landowners, and the status quo.

His role, in this respect, is less analogous to that of Spartacus, a revolutionary fighting for the oppressed, and more akin to historical figures like Bonaparte or Caesar.

This dynamic mirrors imperial history. It was people like Diocletian who ended the Crisis of the Third Century, by rising through the military and earning the confidence of the troops. By doing so, he stabilised the Empire and ushered in a period of relative peace – albeit one that merely delayed its eventual demise.

But what the film does draw out is the need to rise above the fight for survival; to embrace ideas which allow us to truly live, and to free ourselves from oppression and tyranny; and to base ourselves on the class that can make such a society a reality.

For those seeking a ‘medium-brow’ film with a balance of action and dialogue, this sequel delivers plenty to enjoy. However, viewers should temper their expectations – it is a solid and engaging film, but not a masterpiece.