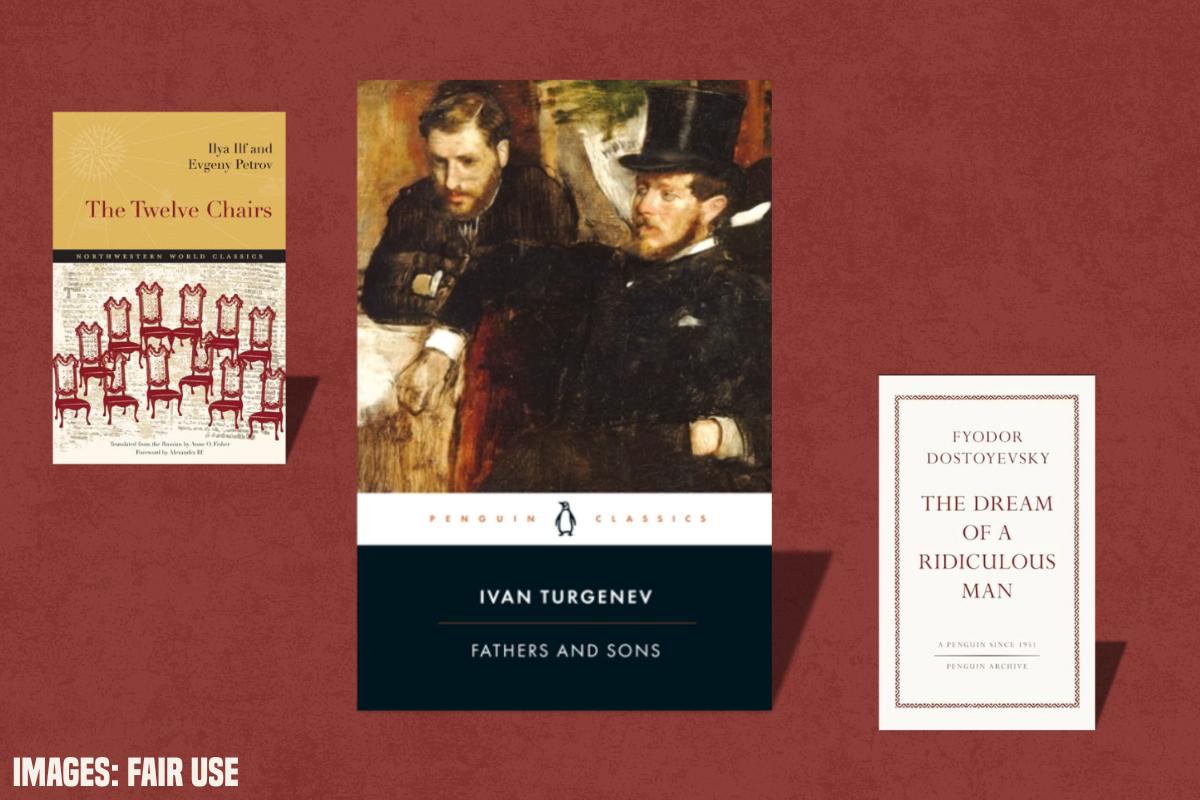

Turgenev’s ‘Fathers and Sons’ – The old versus the new

Mark Anthony, Kingston

Fathers and Sons, released in 1861 but set in 1859, is seen by critics as Ivan Turgenev’s best novel – and for good reason.

Turgenev’s works show his own liberal political beliefs clearly, but this does not hold them back from containing an honest reflection of the developing class struggle in Russia. Like a mirror, Fathers and Sons paints a truthful reflection of mid-18th century Russian society.

Old versus new

The novel’s title draws upon its core theme: the relationship between the new versus the old, told through the framework of the family.

The story follows two young revolutionary students, Arkady and Bazarov, as they try to settle back into their lives at home after being away from university.

In stark contrast to their children’s drive for a new kind of society, their families represent two sides of the old ways of life: Arkady’s father Nikolai and his uncle Pavel represent the old upper class within Russia, and Bazarov’s parents the outlooks of the Russian peasants.

It is through these characters’ relationships – and the gradual demonstration of the depth of their diverging philosophies – the death throes of the old feudal society and the birth pangs of a new society are put under the microscope.

Social change

In this period, Russia was seeing rapid social changes as capitalism emerged, transforming the consciousness of both the middle and lower classes.

This was reflected in new ideas within the lecture halls of Russian universities: science, materialist philosophy, western European sociology – and, a few decades later, Marxism itself.

Whereas in western Europe, these ideas were largely the stock-in-trade of liberalism, in Russia – which was suffering under the heavy weight of an oppressive tsarist regime – these ideas were adopted by the young intelligentsia, who were brimming with rebellion.

Bazarov and Arkady bring these radical ideas home with them. This sceptical outlook – dubbed ‘nihilism’ in Russia – questioned everything, and held nothing as sacred.

As Arkady boldly declares to his aristocratic uncle, “a nihilist is a man who does not bow down before any authority, who does not take any principle on faith, whatever reverence that principle may be enshrined in.”

Nihilism was adopted by many students with fervor. Their desire to rebel against the system eventually developed into the Narodnik movement, which at times adopted conspiratorial methods to try and ignite revolution amongst the peasants, using acts of individual terrorism.

From the same process of intellectual ferment in the youth emerged the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, and later the Bolsheviks.

Nihilism

It was in fact Fathers and Sons which first popularised the term nihilism as a name for this group of philosophical ideas – the popularity of which would later result in the banning of the book within Russia and the author’s exile.

The radicalism of this philosophy captured a mood among the students, as Turgenev shows so brilliantly. In the book, Arkady states:

“[W]e saw that our leading men, our so-called advanced people and reformers, are worthless; that we busy ourselves with rubbish, talk nonsense about art, about unconscious creation, parliamentarism, trial by jury, and the devil knows what – when the real question is daily bread.”

Far from all the hopelessness and passivity associated with nihilism today, this speech drips with a desire for change!

Bazarov and Arkady act as personifications of an uncompromisingly sceptical and rationalist philosophy, which aimed to tear down all that was irrational and obsolete in Tsarist Russia.

They don’t want mere reforms, or the changing of who is in charge. They wish for a rebirth of a new society from the ashes of the old:

“I shall be quite ready to agree with [reforms alone],” [Bazarov] added, getting up, “when you can show me a single institution in our present mode of life, in the family or in society, which does not call for complete and ruthless destruction.”

This desperate desire to set the whole of the existing society ablaze is reflective of the fact that this determined, self-sacrificing layer of isolated young radicals were tragically born too soon to see the arrival of the social class that could carry out such a revolution: the industrial proletariat.

It would take the further development of capitalism, and the efforts of Social Democrats like Plekhanov and later Lenin, to make clear that the way out of the impasse of Russian society was socialist revolution.

Radical ideas

Just like other radical novels of the period, the political ripples Fathers and Sons had were immense. Alongside further popularising nihilist ideas itself, the novel bred Chernyshevsky’s 1863 classic What Is To Be Done? which was written in direct response to Turgenev.

Bazarov was also often referred to as the ‘first Bolshevik’, despite Turgenev’s own politics – in fact, one Bolshevik was so influenced by this novel that he started to call himself Comrade Bazarov!

And although we understand now nihilism cannot provide the way forward for society, it undeniably played a progressive role in Russia: by asserting the questioning of everything, it laid the intellectual groundwork for Marxism to take root.

These were the ideas that transformed Russian society just 56 years after the publication of Fathers and Sons in the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution – the greatest event in all human history.

This novel serves to not only enrich the reader’s understanding of Russia from a historical perspective, but also to understand the development of radical ideas within Russia. In this sense Fathers and Sons is a must read for all comrades!

‘Fathers and Sons’ is available from all booksellers.

Dostoyevsky’s ‘The Dream of a Ridiculous Man’

Joe Attard and Mia Foley Doyle

Since communists are often dismissed as ridiculous utopians, we may feel some kinship with the titular protagonist of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s 1877 short story, The Dream of a Ridiculous Man.

Set in 19th-century St. Petersburg, the titular Ridiculous Man sees no point to the world around him and has vowed to end his life, with the promise of death’s relief giving him license to treat others with contempt.

On the day of his planned suicide, the Man dreams he is spirited away to something resembling a Greek island on another planet. For these innocent and happy islanders all is owned in kind, children are raised collectively, and meanness and greed are foreign concepts.

The Man is finally at peace, but like the serpent in Eden, he brings corruption to paradise.

He unwittingly infects the islanders with deception and self-interest – planting the seeds of what Dostoyevsky’s would call ‘sin’, and Marxists will recognise as class society. The islanders forget their simple ways and love for one another as they begin to covet property, divide into hostile tribes, ravage the islands’ resources, and so on.

Despite this tragedy, upon waking the Man finds purpose in sharing what he has come to understand: that the cruelty of society as it stands is not something innate to humanity, but instead foisted upon us.

He decides to live, blessed with hope for mankind’s future – and cursed to suffer ridicule for this same hope.

The Ridiculous Man calmly accepts this bleak life of scorn and hopeless struggle thanks to his renewed faith in the essential goodness of mankind; a common theme for Dostoyevsky.

Despite his belief no one will listen to his preaching, the hope contained in the Man’s personal journey is no doubt what readers continue to connect with almost 150 years after the story’s publication.

For our part, communists do have faith in the ability of working people to bring an end to the capitalist system. But this will not be by reverting to a simpler way of life, or by enlightened individuals calling for a more loving society.

This will be achieved by ending exploitation through socialist revolution – and utilising our collective knowledge of the world to create a paradise on earth above and beyond anything the Ridiculous Man could dream.

‘The Dream of a Ridiculous Man’ is available to read online here, or from all booksellers.

‘The Twelve Chairs’: A masterpiece of Soviet satire

Callie McIntyre, Sheffield

“You’re a rather nasty man,” retorted Bender.”You’re too fond of money.”

“And I suppose you aren’t?” squeaked Matveyevich in a flute-like voice.

“No, I’m not.”

“Then why do you want sixty thousand?”

“On principle!”

Say to a friend, “I’m reading a novel from the USSR,” and watch their expression turn carefully polite. A nod. A smile. But behind the eyes: “My God. It’s worse than we thought!”

By the following week, expect a flurry of messages – “how are you doing these days?”, “we simply must get lunch together!”, and perhaps a few “You know, therapy has been really working for me lately. Have you ever considered…?”

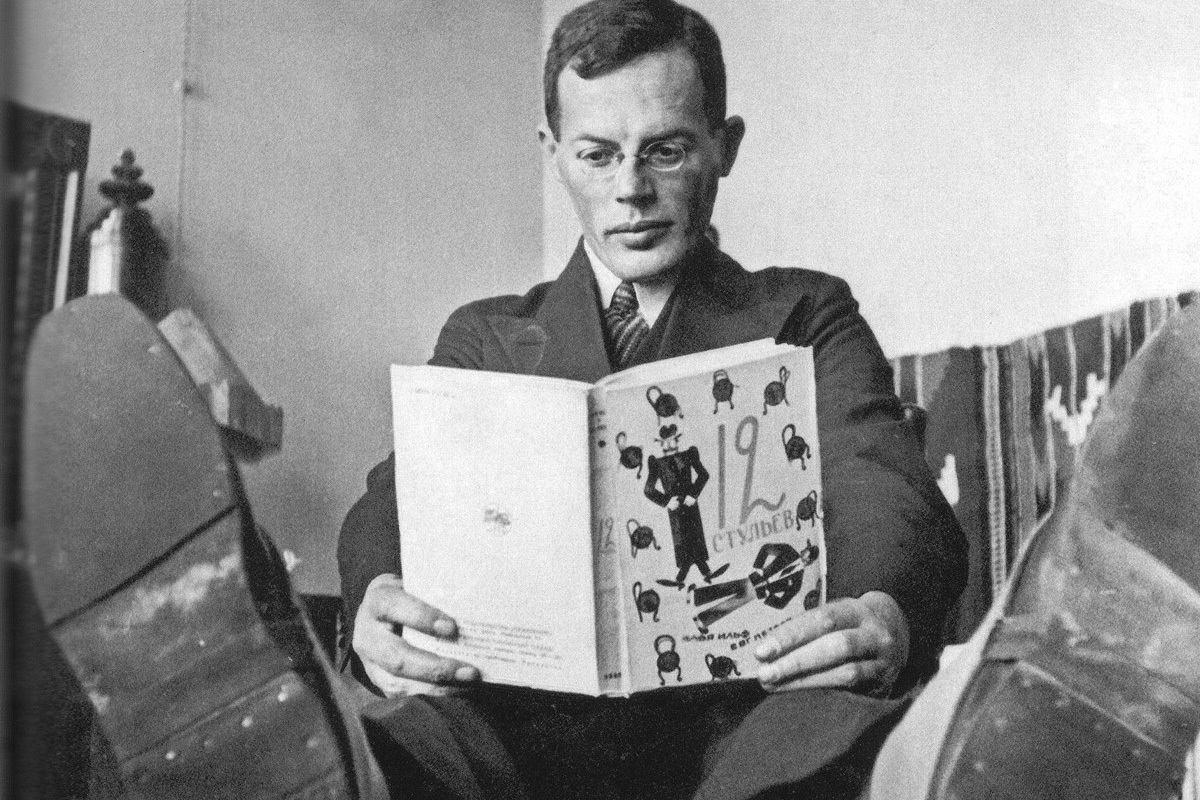

Enough! Believe it or not, life behind the so-called ‘iron-curtain’ was not unending grey monotony; love, laughter, squabbling, and even lively grumbling could all be found. If you want proof of that, look no further than the 1928 satirical masterpiece, The Twelve Chairs.

The novel’s authors, Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov, had moved from Odessa to Moscow in 1923 to work as journalists.

Their specialty was being “readers to the letters” – a traditional means by which the complaints of everyday life were voiced. From the off they had their hands full. This was a period of rising class differentiation that came with the 1921 New Economic Policy.

It was from handling these letters that the idea for a novel emerged: a con artist, a former nobleman, and a priest, all chasing after a cache of jewels hidden in a set of chairs that went missing and were scattered across the country after their appropriation by the Soviet government years before.

The result is the distillation of the working class’ anger and frustration at all the selfish, venal elements of class society. But here, these elements are not allowed a quiet existence. Instead Ilf and Petrov drag out all the landlords, the shopkeepers, the politicians, and reveal them for the clowns they really are.

It is this expression of class anger that makes the novel timeless. But what makes it worth reading most of all is simple: it is funny as hell!

‘The Twelve Chairs’ is available from all booksellers.