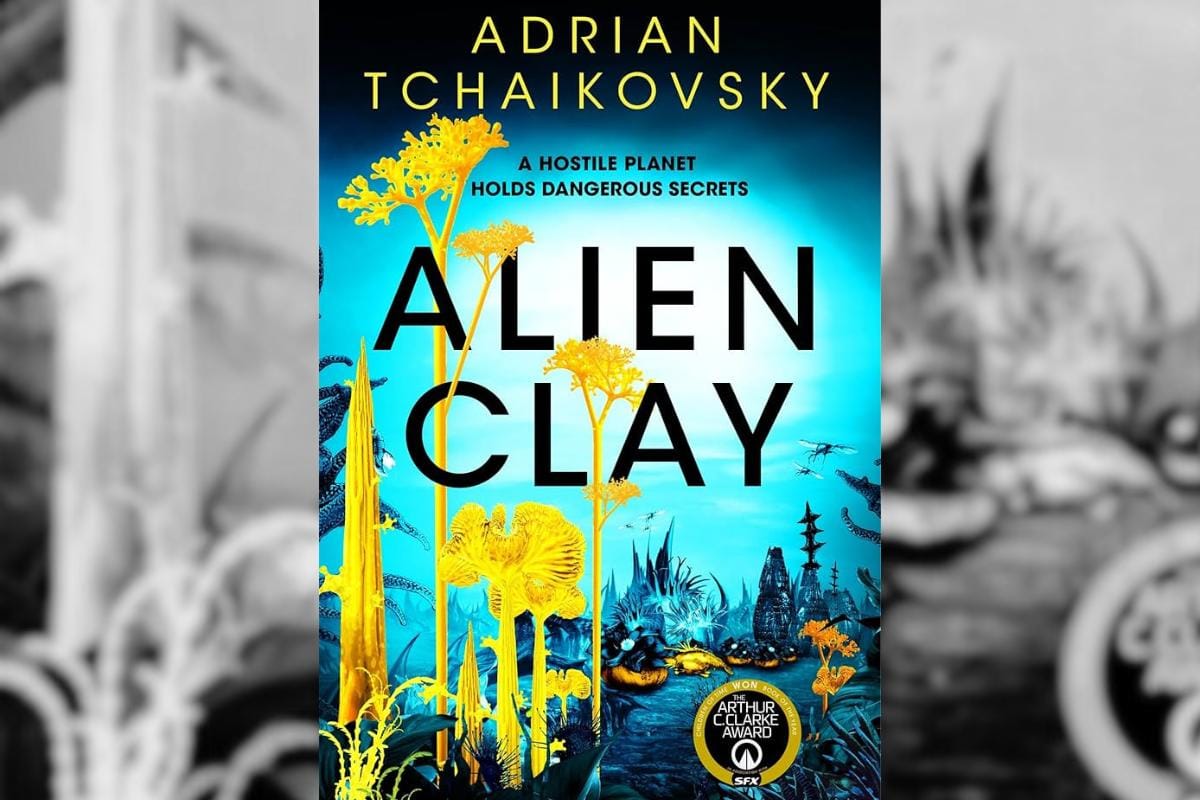

Adrian Tchaikovsky’s recent novel Alien Clay is an excellent read, set in a grim future where humanity is governed by the authoritarian Mandate.

Whilst on the surface it appears to be just another sci-fi, Alien Clay goes much deeper – exploring how science interacts with society, and ultimately how society must be revolutionised in order for science to advance.

Arton Daghdev, an ecologist, has been banished to a labour camp on the planet Kiln for political “unorthodoxy” and revolutionary activity. Here, he is tasked with battling against its inhospitable environment in service of the Mandate’s scientific research – or so we are led to believe.

On Kiln, Daghdev quickly realises how even his understanding of a species is inadequate, faced with animals that are kaleidoscopes of disparate yet cooperating parts.

Imagine that your hands could wander off when they want to find a new body, and you have an idea of Kilnish biology! What is required to understand Kilnish life is nothing short of a paradigm shift.

But scientific discovery has been long stifled by the Mandate’s strict adherence to Earth’s scientific rules.

To solve the mysteries of Kiln, Daghdev realises he needs to think beyond these ‘common sense’ assumptions and examine how Kiln’s species really interact in all their complexity.

Yet the Mandate is not interested in genuinely understanding Kilnish life, but in perpetuating its own power.

As such, any scientific discovery becomes twisted to prove existing Mandate-approved logic, rather than to understand this planet on its own terms. This pantomime is reminiscent of academic gaffs from recent history, namely the “dinosauroid” of palaeontological infamy.

This strangling of science by class society is visible today, with stagnation, faltering innovation, and rising mysticism. As in the novel, today’s politicians are not interested in advancing human knowledge, but clinging to power amidst their decaying regimes.

At first, Daghdev believes that the pursuit of knowledge alone can set humanity free from the Mandate. However, as Trotsky said, “No ruling class has ever voluntarily and peacefully abdicated.”

The dawning realisation of this amongst Daghdev and his fellow prisoners; the tasks that follow; and the subsequent repression at the hands of the state are all captured viscerally in Alien Clay.

Tchaikovsky brilliantly shows this as not just a struggle for basic needs, but a battle for the future of human progress.

We don’t have some of the benefits of the prisoners in Alien Clay in this same struggle; no alien biotechnology for us! But we do have in our hands the levers that cause buses to run, factories to produce, and electricity to flow.

With this, we can also fight to liberate mankind from the stranglehold of government bureaucrats and CEOs, and set it free to plot new paths into the frontiers of science and culture.