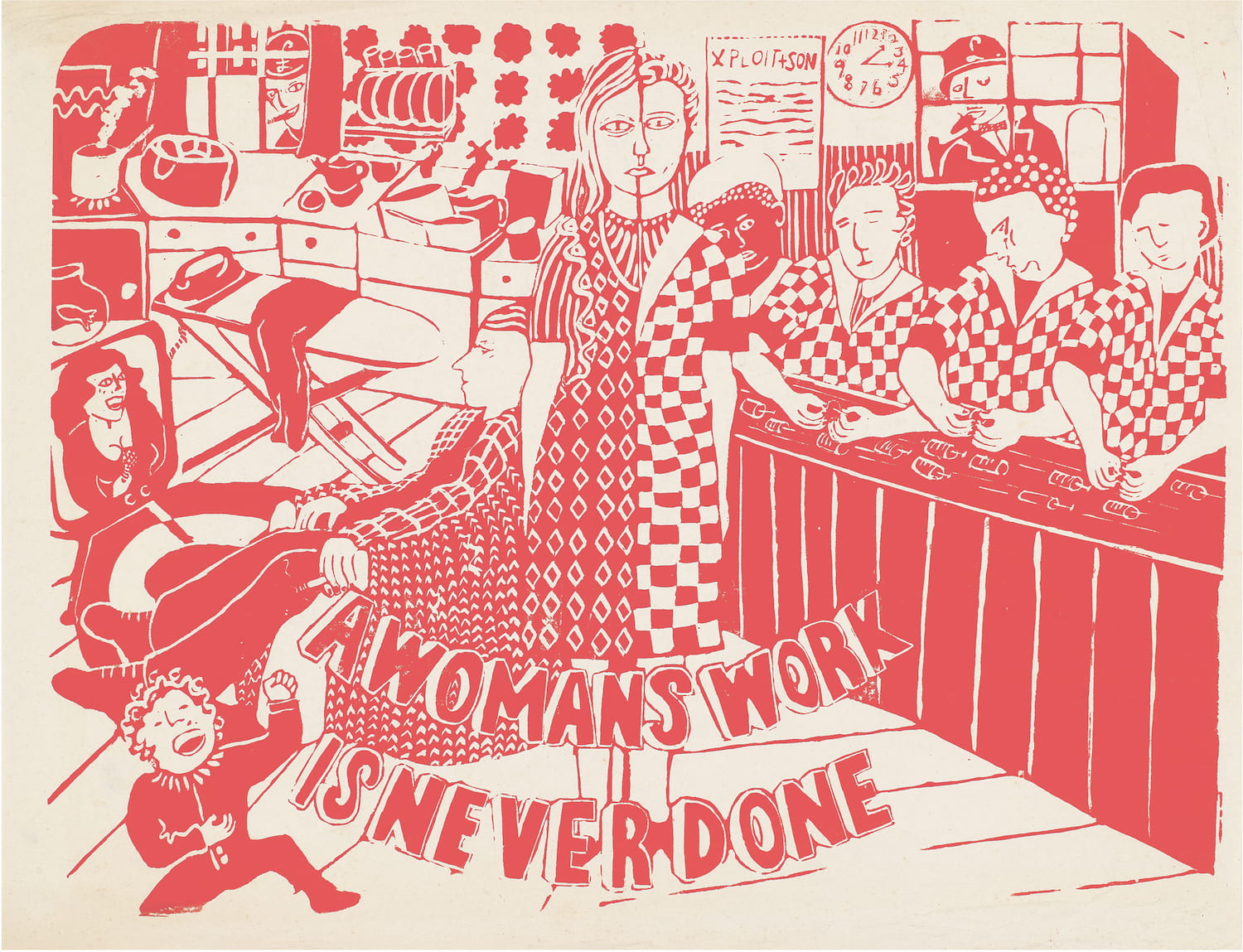

In an article pondering the value of International Women’s day, The Guardian (6.3.95) showed that in 1993 women made up 49.5% of the workforce, but that still “the average female worker earns nearly 40% less than the average male worker.” Choosing to ignore this statistic and focusing instead on social attitudes, it concluded that by the new millennium we should be able to celebrate an “Equality between the Sexes Day”!

A similar blithe disregard for economic reality and concentration on appearances characterises the very organisations which should be fighting for equality. It’s clearly embarrassing for the “modernizers” when TV coverage of conferences exposes the overwhelming male domination of the labour movement. Unfortunately, rather than adopting a fighting programme which would attract low paid women to join, Proportionality has meant that both the Labour Party and the unions have gone down the road of “quotas”, or reserved seats, to increase the visibility of women in their ranks.

UNISON, the public services union, has perhaps gone furthest in its attempts to manipulate the presence of women in its structures. It has introduced a new concept in its structures and rulebook – proportionality. This is the “representation of women and men in fair proportion to the relevant number of female and male members comprising the electorate.”

No-one could disagree with the aim of getting more women to come forward and act as stewards and branch officers. And no-one could disagree with UNISON’s Code of Good Branch Practice which outlines organisational means of improving participation, assisting with childcare and carers support, etc. But nowhere in all the literature stressing the need to encourage women, does the union put forward the kind of programme that most of its women members would really think important: – a serious fight against low pay NOW, not at some eternally receding point in the future:

– a minimum wage.

– free, quality childcare for all who need it.

– a nationally co-ordinated campaign of industrial action against cuts and privatisation of public services.

Proportionality pays lip service to the advancement of women in one public service union. The reality for its members is in stark contrast. “Women workers suffer most as councils tender out services”, ran a recent Guardian headline, quoting an Equal Opportunities Commission report currently being edited. This shows a 21% drop in council manual jobs since Compulsory Competitive Tendering was forced through in 1988, a figure which “masks the effect on women because 97% of the jobs are done by them… In catering and cleaning 11,300 women’s jobs had gone compared to 591 men’s.”

And apart from the job losses, “women workers have lost pay, employment and pension protection.”The report concludes that amongst other causes “CCT has clearly accelerated job losses and has been the main cause of cuts in pay and conditions of service.”

Where was, or is, the fight against compulsory tendering? The Labour leadership have been largely silent. NUPE, and now UNISON leave branches to fight alone as best they can. And whether jobs or conditions are saved at all depends randomly on a determined branch or regional official taking up the issue, generally through a legal battle on transfer of undertakings.

Women are not only the main victims in the workplace, they suffer a double blow as the main consumers of public services for elderly relations, under 5s or school age children, etc. as these are relentlessly cut back. The figures in the EOC report undermine the thinking behind UNISON’s equal opportunities policies.

Clearly, proportionality is not working in the interests of women members but acts as a career route for a tiny minority within the union. It offers the union’s women members nothing in their fight against CCT and cuts. It is used by the union leadership as a “radical” cover for its lack of activity over government attacks on public spending which disproportionately affect women employees.

Combined with UNISON’s other innovative concept “fair representation” for manual and non-manual workers, race, sexuality and disability, as well as reserved seats have become a recipe for divide and rule.

Reserving seats for one group can upset another. Reserving them for all denies the members the right to choose their representatives on the basis of ability, commitment and ideas. Quotas may mean incompetent or self-serving members get on a branch committee and be impossible to dislodge through election. Part and parcel of this has been the introduction of so-called “weighting”. Is a male manual worker worth more than a female white-collar worker? Is a black man worth more than a white woman? Who can adjudicate on such issues? And what have they got to do with a trade union’s primary duty to fight for the terms, conditions and jobs of all its members?

Proportionality has meant that the energy of a branch can be dissipated in internal wrangling as different groups vie for positions. The fight against management can become less important than the fight against each other. No wonder the union officials appreciate the value of reserved seats! There is no shortcut to equality and no alternative to the hard work of seriously addressing the issues which most affect women in order to get them to participate actively in the labour movement. For most women, there will almost always be something more pressing to do than attend a meeting – the dinner to cook, the children to see to – unless it directly touches their experience and promises a serious, concrete effort to improve their conditions. And not until the mass of women become involved will women activists develop in greater numbers. Reserved seats, presented by “modernizers” as the solution to the under-representation of women, are in reality a harmful diversion from the true route to equality. And this is inseparable from the fight to transform society.

Socialist Appeal, April 1995