Socialist Appeal are proud to publicise a new podcast series by Alan Woods on the English Revolution of the 17th century. Subscribe to Marxist Voice to listen to weekly installments of Alan discussing these dramatic and revolutionary events.

In this series, entitled The English Revolution: the world turned upside down, Alan provides an in-depth examination of the dynamics of the revolution, drawing out the vital lessons for socialists today.

Tune in to Marxist Voice each week, every Friday, as Alan provides a Marxist analysis of this important chapter in British history; this colossal event that dealt an irreparable blow to feudal absolutism and paved the way for modern democracy as we know it.

See below for episode two of the series, where Alan’s explains the important role of religion and the Reformation in the Revolution.

And if this series sparks an interest in Britain’s radical past, please head over to our publishing house Wellred Books, and grab yourself a copy of Socialist Appeal’s new pamphlet on Britain’s Forgotten Revolutionary History, which is available now digitally.

To supplement this new podcast series, we are also republishing articles from our archive on the subject of the English Revolution. First up, below, is an article by Socialist Appeal editor Rob Sewell, who looks at the events covered by the first few episodes of Alan’s series, leading up to the outbreak of the Civil War in 1642.

“The war was begun in our streets before the King or Parliament had any armies.” – Richard Baxter

The British bourgeoisie and its apologists have always tried to bury their revolutionary past. They continually promote the false idea that ‘gradualism’ has always been the true British tradition.

Revolutions were always affairs of the continent, but have no relevance here. Histories and documentaries are produced in an attempt to hide the real significance of the English Civil War of 1642-49 – the bourgeois revolution that destroyed the old feudal order in England and laid the basis for the development of modern capitalism.

The Civil War was in fact a class war which destroyed the despotism of Charles I and the feudal classes that stood behind him. It was a great social revolution on the lines of the French Revolution of 1789-93.

While bourgeois historians describe the deep-seated social revolution of the 1640s as an unfortunate incident, namely the ‘Great Rebellion’, they christen the shuffling of crowns in 1688 as the ‘Glorious Revolution’, which was hardly glorious or a revolution.

The present ‘men of property’ attempt to erase from memory the revolutionary role of their ancestors, a revolutionary class, which by means of civil war beheaded a monarch, abolished the House of Lords, and declared a revolutionary Republic – so out of character with the British ‘tradition’ as presented in our school books.

As Leon Trotsky explained, the French bourgeoisie, having falsified their revolution, adopted it and, changing it into small coinage, put it into daily circulation. In Britain, meanwhile: “The British bourgeoisie has erased the very memory of the seventeenth-century revolution by dissolving its past in ‘gradualness’.”

Nevertheless, Trotsky explained that it was important for advanced workers and youth to re-discover the English revolution. In this epic drama the British working class can find great precedents for future revolutionary deeds. “This is equally a national tradition,” notes Trotsky, “and a thoroughly legitimate one that is wholly in place in the arsenal of the working class.”

Reformation

England in 1640 was on the verge of a social revolution. The old feudal order had exhausted its historic role. But, as Marxism explains, no ruling class voluntarily gives up its privileged position without a struggle. This was no exception.

England in 1640 was on the verge of a social revolution. The old feudal order had exhausted its historic role. But, as Marxism explains, no ruling class voluntarily gives up its privileged position without a struggle. This was no exception.

For some time the capitalist mode of production was encroaching steadily on the old feudal relationships and its static “‘natural’ economy. The new forces of capitalism were steadily breaking through. The new economic forces over the previous century had served to put the last nails in the old order.

The widespread inflation, largely brought about by currency debasement and the robbery of gold and silver from the Americas, served to undermine feudal society. In England, between 1510 and 1558, food prices had trebled. Textile prices rose by 150%.

Money relations replaced duties in kind, as land was turned by enterprising gentry into profitable investments, producing food and wool for an expanding market. Merchants became very rich, while the wealth of the old aristocracy, dependent on fixed incomes, declined in real terms. The old static order, based on feudal tradition, custom and social rank, was on its last legs, holding on like grim death.

The Reformation, begun by Henry VIII’s break with Rome to solve his matrimonial problems, not only turned England into an independent protestant country free from Papal interference, but led to the widespread sale of expropriated church lands.

This had the whole-hearted support of the rising bourgeoisie, which benefited greatly from this protestant reformation. At this time, the bourgeoisie and townspeople were loyal supporters of the Crown and strong central government. The ever-feuding aristocracy, as witnessed by the Wars of the Roses, was a menace to trade and money-making.

The first Tudor monarch, Henry VII, tried to solve this by systematically murdering all those who had any claim to the throne! The Tudor monarchs, especially Henry VIII and Elisabeth I, made England safe for trade, both internally and externally.

The Catholic Mary Stuart was beheaded in 1587, removing the figure-head of plots and Catholic restoration. Finally, the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 allowed English goods to be traded freely and commerce to develop.

The defeat of Spain, the strongest power in Europe, leader of the Papacy’s counter-reformation, provided a colossal boost to England’s national standing. The new task was to break the colonial monopoly that Spain had established in the West.

Rising bourgeoisie

The development of wealthy merchants, grown rich on trade, piracy, plunder and the slave trade, went hand in hand with the rise of capitalist farmers keen to enclose common land and rack up rents. Stable relations were breaking down as copyholders, which had a degree of security, were turned into leaseholders. A sharp differentiation took place in the peasantry.

The new well-to-do gentry began to take over local government as Justices of the Peace and a number made their way into Parliament, a body made up overwhelmingly of landowners elected by landowners.

These capitalist gentry were concentrated largely in the South and the South East, near the market of London and in the ports. For the rising bourgeoisie, Protestantism and English patriotism were closely bound together.

By the time of Elizabeth’s death and the coming of James I and Charles I, the situation had fundamentally changed. The old ruling classes had become increasingly parasitic, desperate to hang on to their declining wealth, privileges and social position. These parasites (‘Drones’ as they were called) looked to the Crown and Court for support and wealth, which in turn defended the old order.

The rising bourgeoisie, on the other hand, was chafing under the impediments imposed by the ancien regime, which led to a whole series of clashes in the House of Commons. While the threats from internal and external enemies had been resolved, the bourgeoisie now demanded policies that were to their liking. The social relations and legal framework on which the old order was based would have to be removed if capitalism was to develop.

Role of religion

At this time, religion played a very important role, interwoven with politics, economics and social issues. In fact, everything was seen in religious terms.

At this time, religion played a very important role, interwoven with politics, economics and social issues. In fact, everything was seen in religious terms.

On an international level, Protestantism accompanied the rise of capitalism and suited the ideological outlook of the rising bourgeoisie. The international Catholic Church was a bulwark of Feudalism and the Old Order.

The teachings of Luther and Calvin broke down the old ideology. Its stress on individual conscience, individual success, thrift, hard work – as explained by Tawney in Religion and the Rise of Capitalism – contributed to the development of a capitalist outlook.

The Reformation in England had far reaching consequences, especially the spread of Protestantism, but with the sale of Church lands and monasteries, it also created a vested interest in the new religion.

Protestantism was the philosophy of the prosperous God-fearing Englishman, the backbone of the rising bourgeoisie. He was one of the Lord’s chosen people, the elect. Not unimportantly, Protestantism was also a cheaper religion than Catholicism, with its numerous wasteful Saints’ days and religious ceremonies and artifices.

The Reformation even called into question the whole hierarchical principle, with Puritans wanting it to be carried further with the abolition of bishops, the mainstay of Royal power.

Every man, woman and child was a member of the protestant Church of England, which played a decisive role in peoples’ lives. They had to attend parish church services every Sunday or face punishment by Church courts, which also ruled over morality, failure to pay tithes to the clergy, as well as working on saint days. The parish was the real social unit.

As there were no newspapers, radio or TV, the pulpit was a most powerful instrument used for government announcements. Books were all censored by Bishops and education was an ecclesiastical monopoly.

“People are governed by the pulpit more than the sword in time of peace,” said Charles I. “Religion it is that keeps the subject in obedience,” agreed Sir John Eliot. Thus a struggle for power would also assume a struggle for control of the church.

“No Bishop, no King, no nobility”, stated James I. The three stood or fell together. “The dependency of the Church upon the Crown,” explained Charles, “is the chiefest support of regal authority.” Religion played a vital rallying cry for the contending classes.

Debts and decline

Throughout this period, the income of the Crown, as with the aristocracy as a whole, was declining in face of inflationary pressures. Debts were building up. Meanwhile, the ‘country’ and those classes represented in Parliament were getting richer.

Throughout this period, the income of the Crown, as with the aristocracy as a whole, was declining in face of inflationary pressures. Debts were building up. Meanwhile, the ‘country’ and those classes represented in Parliament were getting richer.

The only way out for James I and Charles I was to raise further taxation on trade and by reviving and levying greater feudal impositions. This included increasing fines, selling monopolies, peerages and ranks, but none of which provided adequate income.

A series of conflicts blew up between King and Commons over these issues. When Charles I demanded money for new wars, Parliament refused and was dissolved. He resorted to forced loans and imprisoned those who refused to pay. In 1628 martial law was imposed.

All these grievances and more were brought together in the Petition of Right in 1628. But this led to further clashes. Finally, the Speaker of the Commons was held down in his chair while the House passed three resolutions, ending with anyone laying taxes without parliamentary consent would be regarded as “a capital enemy to the kingdom and commonwealth”.

Parliament was dismissed, and the King embarked on eleven years of personal government. In these years, Charles managed to alienate all those propertied classes that had previously supported him.

The King had to rely more and more on the church in this period, the nearest thing to an independent bureaucracy.

Archbishop Laud, in essence Charles’ Prime Minister, attempted to boost the declining authority of the church by attempting to turn back the clock, which simply alienated large sections of the propertied classes. Bishops as royal nominees were seen as yes-men of the court, sympathetic to royal absolutism and the enemies of Parliament. They were regarded as appeasers to Catholicism and the Papacy, which reinforced the passionate popular hatred of bishops.

All kinds of expedients were tried to raise finance independent of Parliament from fines for enclosures to fines for refusing knighthoods. However, the most important was levying Ship Money, a tax on ports for defence, which was unilaterally extended throughout the country. Those who refused to pay were jailed.

“What shall freemen differ from the ancient bondsmen and villeins of England if their estates be subject to arbitrary taxes?” stated Sir Simonds D’Ewes.

This led to widespread resistance. By 1638, sixty-one per cent of the tax was unpaid. The government could not balance its books and the City of London refused a loan. The situation was brought to ahead when the Calvinist Scottish Army invaded England and Charles had little money to pay the troops levied to oppose them, while the army proved unwilling to fight.

Long Parliament

Charles’ personal government was collapsing around his ears. Even a section of the old ruling class – the aristocracy and gentry – came out against him. Men like Hyde and Falkland, who were no Puritans and fought for King in the Civil War, sided with the majority in denouncing royal absolutism.

Charles’ personal government was collapsing around his ears. Even a section of the old ruling class – the aristocracy and gentry – came out against him. Men like Hyde and Falkland, who were no Puritans and fought for King in the Civil War, sided with the majority in denouncing royal absolutism.

In other words there was a deep split in the ruling class. Such a split is the first premise of all revolutions. The old order had lost the support of its social reserves. As with the beginning of the French Revolution, there was a “revolt of the nobility”, which served to open the floodgates and attracted to it all those who felt the regime was a threat to “religion, liberty and property”.

For financial reasons, Charles was forced to recall Parliament. After three weeks, Parliament was again dissolved. But within six months Charles was again forced to summon Parliament.

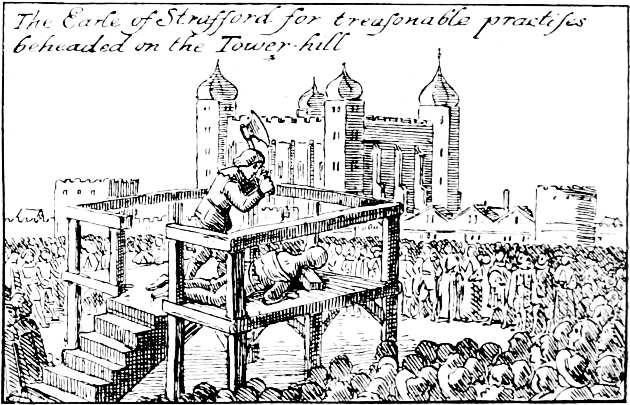

When the Long Parliament finally met, no compromise could be reached. In an unprecedented fashion, the Commons immediately impeached the King’s ministers, the Earl of Strafford and Archbishop Laud, accusing them of treason and sending them for trial before the Lords. Other ministers fled the country.

Stafford was beheaded for treason on Tower Hill in May 1641. A crowd of some 200,000 attended the popular execution. Laud was imprisoned in the Tower and executed in 1645. The prerogative courts of Star Chamber, Council of the North and Wales as well as the High Commission were abolished. Taxation without parliamentary consent was declared illegal and the Long Parliament declared indissoluble except by its own consent.

Nevertheless, few members of the Long Parliament at this time were republicans or dreamed of doing more than limiting the powers of the King. Both parties attempted to manoeuvre one another into a false position. They could see no further than the next step. Yet what was achieved was the destruction of the main pillars of the old state apparatus. The English Revolution had begun. There was no turning back.

Masses enter the scene

While in the French Revolution, the nobility quickly rallied to the Crown after the Third Estate put forward revolutionary demands, in England the House of Commons split and carried their opposition to the point of civil war.

While in the French Revolution, the nobility quickly rallied to the Crown after the Third Estate put forward revolutionary demands, in England the House of Commons split and carried their opposition to the point of civil war.

Religion was used as a rallying cry. But “religion was not the thing at first contested for,” noted Cromwell. There was a real popular hostility to the old regime. The economic and political turmoil of the previous twenty years had taken its toll.

In an unprecedented fashion, huge London crowds marched on the Commons to demonstrate their support, often with menaces, further widening the divisions. The government’s whole repressive machinery and its censorship collapsed like a tower of cards.

Religious sectaries emerged from underground; an outpouring of pamphleteering began; there were riots over enclosures and against papists.

Rumors of a Catholic plot in the Army at York to march on the capital produced panic in London, which had become the centre of revolutionary ferment and discussion. All those who had a grievance now flocked to Parliament to seek redress.

At this time there was no Royalist Party, but events would serve to crystalise one. Every gesture to gain the support of the lower orders outside Parliament led to the loss of some support from the gentry alarmed at the “many-headed monster”.

As a sign of things to come, in August 1641, the Commons were divided for the first time over the Root and Branch Bill to abolish bishops and reorganize the Church under the control of Parliament.

This was at a time of heightened public excitement. Matters came to a head with the outbreak of rebellion in Ireland in October, eager to break free from the grip imposed by Stafford. Who was to command the army? The parliamentary leaders knew he would as soon as use the army against them as the rebellious Irish.

The bourgeois leaders around John Pym who used the opportunity to bring before the Commons the Grand Remonstrance, a comprehensive list of claims against Charles’ autocratic government.

Having got it passed, they pushed through another vote for it to be printed. This unprecedented step constituted a direct appeal to the people outside parliament. Such a reckless and dangerous move by the ruling political elite served to split Parliament and the country into two camps.

Such a move resulted from a desperate situation. Everything was on a knife edge. Lives were at stake. Swords were drawn in the Commons. The Remonstrance only carried by eleven votes. Charles I had made it clear that he would seek revenge at the earliest opportunity.

Within a space of weeks, on 4 January 1642, Charles staged a botched coup and attempted to arrest the key parliamentary leaders. But they had fled to the safety of the City of London.

On 10th January, Charles fled to York to drum up support in his defence and the defence of the Old Order. After several months of propaganda by both sides, war finally broke out in August 1642.

Within the next seven years, Charles would be defeated and beheaded, and the Monarchy abolished. The English Revolution – a decisive turning point in history – had well and truly begun.