Trotsky warned in 1940 that the attempt to solve the ‘Jewish problem’ in Europe through the dispossession of the Palestinians would be a “bloody trap”. These words ring true to this very day. But the real history of Israel-Palestine has been buried under mountains of falsification.

In this article, Francesco Merli explains the shady dealings and machinations of the imperialist nations that paved the way for the partitioning of historic Palestine. This episode in history attests to the short-sightedness of the ruling class, who opened up a Pandora’s box of violence and degradation that has plagued the land ever since.

This article is Part I of a two-part series, the second of which will deal with events following the partition of Palestine. The series is part of a set of articles produced for our new pamphlet, ‘Israel-Palestine: a Revolutionary Way Forward‘. These are abridged versions of longer articles which will be published on the In Defence of Marxism website in future months.

Read the introduction to this article series here.

Over the past one-hundred years, the Middle East has been the chessboard for many decisive games between the imperialist powers. The reason for the relevance of the region, considered of relatively secondary importance until the end of the 19th century, is well known: beneath the lands of the Middle East lie the planet’s main oil reserves. Palestine, for a number of geo-political and historical reasons, has increasingly become the focus of Middle Eastern tensions.

The long drawn-out process of decomposition of the Ottoman Empire suddenly accelerated with the ‘Young Turk’ Revolution of July 1908, but was completed only after the Empire’s defeat in the First World War.

Already, the Empire had lost control over part of its European provinces in the course of the 19th century. Over that period Britain and France had also seized control over large parts of North Africa. France took over Algeria in 1830 and occupied Tunisia in 1881. Britain invaded Egypt and Sudan in 1882. Even a secondary power such as Italy took a slice of the Empire by occupying Libya in 1911.

The government of the Young Turks entered the War alongside the Central Powers, Germany and Austria-Hungary. Long before the end of the War Britain and France had already reached an understanding on how to share among themselves the spoils of the Empire.

Accustomed to dominating vast colonial empires, the British and French agreed on creating a series of states artificially separated by borders arbitrarily drawn with a ruler on geographical maps. The deal was sealed by the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement (with the consent of Russia and Italy) in January 1916.

The deal was denounced and published by the Bolsheviks in November 1917, immediately after the Revolution, to the dismay of the imperialists. However, after the War, the partition happened along the lines agreed upon by Sykes and Picot. France took control over Syria and Lebanon. Britain was recognised a mandate over Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), Palestine and a protectorate over the puppet monarchy of Transjordan (now Jordan).

The British imperialists had cynically raised the hopes of the Arab nationalists for an Arab homeland. A negotiation along these lines was established by Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner to Egypt, in his correspondence to Hussein bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca, in exchange for Arab support in the War. The Arab insurgence against the Ottomans played a key role in the demise of the Ottoman Empire.

However, the British imperialists had no intention of honouring their promises and were more interested in expanding their own sphere of influence. The rise of Arab national consciousness represented a strategic threat to their imperialist interests.

The Jewish question and Zionism

The history of Jewish immigration to Palestine is closely woven with the rise of the Zionist movement at the end of the 19th century. Until then, the indigenous Jewish population living in Palestine amounted to a few thousand people, mostly concentrated in the urban areas.

A turning point came with the wave of pogroms unleashed in the Russian empire by the secret police against the Jewish minority, held responsible for the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881.

Angry mobs whipped up by hired provocateurs stormed Jewish neighbourhoods, looting them and assaulting the population. Hundreds of thousands of Jews were driven out of Russia and the Ukraine to escape the terror campaign of killings, beatings, rapes, lynchings and the destruction of their livelihood and properties.

More waves of pogroms followed in 1903-6, and an even bigger one in 1917 and 1921, unleashed by the White armies during the civil war against the Bolshevik revolution.

At the end of the 19th century another episode sent enormous shockwaves. In 1894-95 Alfred Dreyfus, a French Jewish officer, was wrongfully convicted for treason. His trial unleashed a wave of anti-Semitism in France.

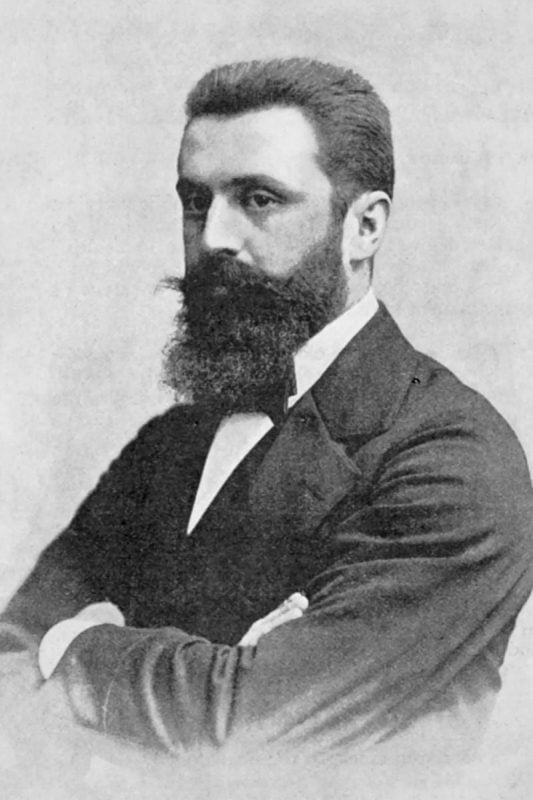

The “Dreyfus affair” played an important role in the conversion to Zionism of a cosmopolitan Jewish bourgeois intellectual, Theodor Herzl (1860-1904). In fact, Herzl wrote The Jewish State, what would become the political manifesto of Zionism, in the aftermath of the trial.

Herzl became the main organiser and theoretician of the Zionist movement, and developed it as an international force. He devised the tactics of organising mass emigration of Jews from Europe to Palestine.

He also came to the conclusion that the growth of anti-Semitic tendencies in Europe was to be regarded as a potential help for the Zionist project, a means of putting pressure on what he regarded as secular Jewish inertia.

Hence, the Zionist political project was based on the effort to lobby European heads of state and ministers (often fervently anti-Semitic) in the attempt to persuade them that the emigration of Jews to Palestine represented a golden opportunity to rid themselves of the Jewish problem, as well as the fact that a Jewish state in Palestine could be useful to the great powers as an “outpost of European civilisation against Asian barbarism”.

From the very beginning the Zionist project had to rely on the patronage of one of the main imperialist powers as a guarantee for its success.

Herzl publicly reassured the Ottoman authorities that Jewish immigration would only materially benefit the Empire, in order to ensure the necessary compliance of the Ottoman authorities. However, in private he recognised that there could be no Jewish state without the expropriation and expulsion of the Palestinians.

“We must expropriate gently. […] We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it any employment in our country. […] Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.” Herzl noted in his diary in 1895 (quoted in B. Morris, Righteous Victims).

The realisation of the Zionist reactionary utopia converted Palestine into a battleground and would cost the Palestinians (but also the Jewish settlers) unspeakable suffering. Its reactionary consequences last to the present day.

The Zionist movement at the beginning of the 20th century, however, still represented only a tiny minority, confined to a small circle of Jewish bourgeois and petty-bourgeois intellectuals and patrons.

The development of Arab national consciousness

A constant cause of concern for the Zionist leadership was that Arab workers would organise against their exploitation. Another fear was that the development of an Arab national consciousness would unify the Arabs in resisting Zionist colonisation.

Arab national consciousness started developing in the 1880s. The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 raised hopes of emancipation for all the peoples across the Ottoman empire.

The rapid turn of the new regime towards Turkish nationalism accelerated the mass process of precipitation of national consciousness among all the peoples of the Empire, particularly among the Arabs, who shared a territory spanning from the modern Iraq to Morocco, a common language and tradition.

In Palestine such a process became even sharper due to the growing hostility towards the consequences of Jewish immigration. Every land acquisition by the settlers entailed the automatic expulsion of the Palestinian farmers, often unaware that the official absentee owners of the land had sold it to the newcomers, enticed by the rising price of the land.

According to the historian Benny Morris, the average land price jumped from 5.3 Palestinian pounds per dunam in 1929 to 23.3 in 1935. The price of land in 1944 amounted to 50 times that of 1910.

The settlers did not speak Arabic, nor were they familiar with local culture and traditions, and in many cases did not care to learn them, violating long established customs, common lands, pastures, and above all, access to water. It wasn’t long before the Palestinians felt a growing sense of looming threat from the continuous influx of settlers.

The Balfour Declaration

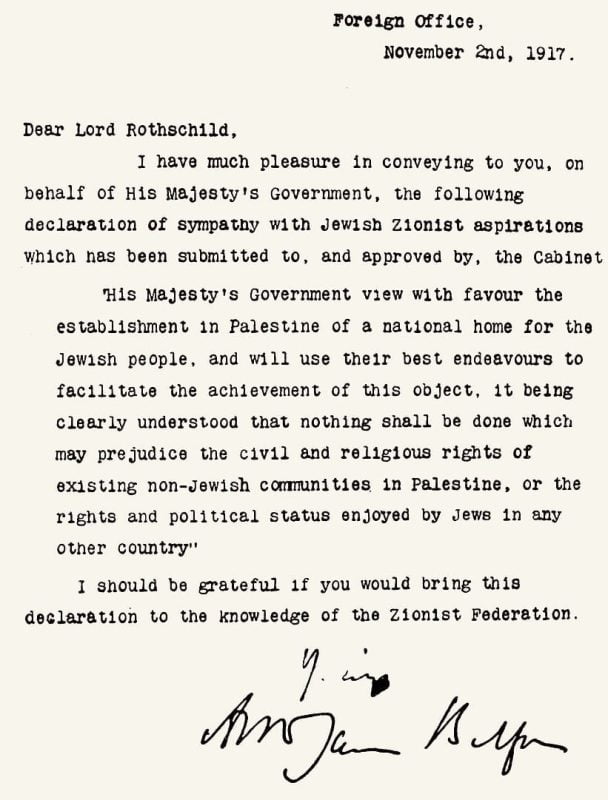

The strategists of British imperialism became interested. They understood that the Zionist project could become a useful tool to pursue Britain’s plans for the Middle East after the demise of the Ottoman Empire.

On 2nd November 1917, this shift was summed up in the letter addressed on behalf of the British government by Lord Balfour to Lord Rothschild and the Zionist Federation. The declaration states:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the right and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

The subordinate clause clearly showed that even at the time, the British imperialists had an evident understanding of the implications of their endorsement. On a capitalist basis, the so-called “solution” to the age-old oppression of the Jews, necessarily led to the deflagration of the “Palestinian question”.

In 1923, a right-wing Zionist, Vladimir Jabotinsky, wrote his political manifesto, The Iron Wall. He recognised the importance of the Balfour declaration, and argued that the Palestinians had to be forced into submission with an “iron wall of Jewish bayonets” and, he added, “British bayonets”. In his view, the viability of the Zionist project relied on the active support and patronage of British imperialism.

Such support became a reality after the collapse of the Ottoman empire and the establishment of the British mandate over Palestine.

Under British rule, the Zionists were allowed to develop the institutions of a semi-state: the Jewish Agency as an embryonic government; the Jewish National Fund as a way to channel finances and buy land, and most importantly, a Jewish Militia – the Haganah.

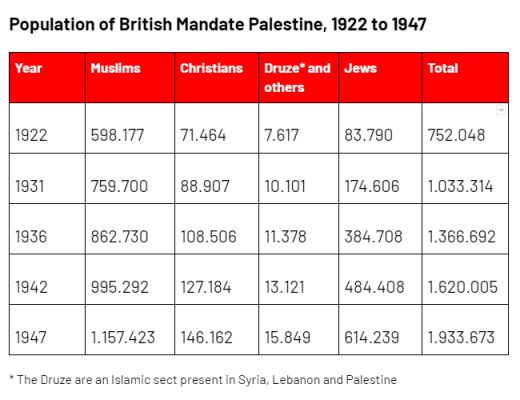

However, at the outbreak of the First World War, there were still no more than 60,000 Jews in Palestine, while the land purchased up to 1908 corresponded to only 1.5 percent of the available land. In the 1920s – as a result of the British Mandate over Palestine – the flow of new settlers accelerated.

In 1929, the overall balance of Jewish emigration since 1880 was as follows: out of about 4 million Jews who emigrated in that period from Central and Eastern Europe, only 120,000 went to Palestine (some of these only temporarily), compared to 2.9 million to the United States, 210,000 to Britain, 180,000 to Argentina, 125,000 to Canada. The settler Jewish population in Palestine was growing, having reached 150,000 in 1929, and rising to over 400,000 by 1936.

The increasing frictions between Palestinians and settlers culminated with the Jaffa riots of May 1921, with dozens of people killed on both sides.

In August 1929, an uprising of the Palestinians against the British occupation turned bloody, with a series of attacks launched against Jewish communities. One of these attacks hit the small Palestinian Jewish community of Hebron (about 600 people), a community dating back to the 16th century.

As a result of the attack, 66 Jews were killed, in spite of the attempt by many Palestinians to protect those fleeing by hosting them in their homes. The Jewish community in Hebron was wiped out. The Haganah repelled other attacks. However, tragically, the death toll of the “bloody days” of August 1929 was 133 Jews and 116 Palestinians.

This gave a decisive impulse to the consolidation of the Jewish militia, the Haganah, increasingly in collaboration with the British occupier.

The formation of the Palestinian Communist Party

During the 1920s and 1930s, opportunities did arise for the building of a revolutionary alternative, based on the working class, which could have avoided the outbreak of a civil war in which Jewish and Arab workers would have everything to lose.

In the early 1920s, the presence of the British colonial administration fostered a certain degree of industrial development of the coastal strip, helping to create an economic sector where Jewish and Palestinian workers worked side by side. This development had an impact on the predominantly rural Palestinian economy and led to intense immigration from the countryside to the coastal cities.

Around the colonial administration arose the railways, the telephone company, the post office and telegraph, ports and shipyards, civil administrations to which were added the local administrations of the cities with a mixed population, and also in the private sector some large companies with foreign capital employed Jewish and Palestinian labour. For example, the Nesher cement factory, the terminal of the Iraqi Oil Company and the refinery in Haifa, and the rapidly expanding building industry.

Between the 1922 and 1931 census, the Palestinian Arab population had grown by 40% and in cities like Jaffa and Haifa by 63% and 87% respectively. The newcomers swelled the ranks of the proletariat in every sector, quickly fuelling a remarkable surge of trade union struggles. Immigration from the countryside was joined by immigration from neighbouring countries, especially Egypt.

The lack of Jewish workforce to replace Arab labour very often led to importing cheap Jewish labourers into Palestine from Yemen or the Maghreb. They constituted a section of the Jewish working class that was particularly exploited and distant from the majority of the Zionists of European origin, who mostly spoke Yiddish and occupied all the leading positions in the Zionist institutions.

It was in this period that the growing divide between Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews (descendants of the diaspora of Spanish Jews who settled in the Ottoman empire) arose, which still characterises Israeli society today.

The Sephardim expressed themselves in Ladino, a dialect derived from Spanish. They were often able to speak or understand Arabic and occupied a social rung slightly above the mass of the Arab proletariat. Under these conditions, class consciousness quickly arose among this layer, who instinctively felt closer to the Arabs than to the big Jewish tycoons like Rothschild and company.

The Zionist “socialist” parties, however, bitterly opposed any demand to open the Jewish workers’ unions to the Arab workers.

The differences ranged from David Ben-Gurion’s Hadut Haavoda, who were in favour of the unionisation of the Arabs but in separate organisations of “equal dignity” (under Zionist leadership), and that of Hayyim Arlosoff’s Hapoel Hatzair, who defended the exclusively Jewish character of the trade union organisation in order to promote an increasing division of labour between a Jewish labour aristocracy with the most skilled and best paid jobs and a mass of unorganised Arab manual labourers.

A third position was expressed by another party of the Zionist left, the Po’aley Tziyon. This party shifted to semi-revolutionary positions by seeking membership of the Communist International (CI) in 1924, though not fully renouncing Zionism. The CI refused to accept a party that was not completely freed from Zionism. This led to a split and the founding of the Palestinian Communist Party (PCP). The new party was immediately expelled from the Zionist trade union Histadrut.

Workers’ struggles and class unity

The PCP defended a position in favour of united trade unions, without discrimination along national or religious lines. By pursuing this political line, the PCP was able to take advantage of the growing militancy and the demand for unity arising from the workers’ experience. Such instinct towards unity, however, was opposed and hindered by both the Zionist leadership and the Arab nationalists.

The PCP grew roots among both the Arab and the Jewish working class. The party published two newspapers in two languages. Despite having its main base of support among the Arab workers, the PCP won 8% of the vote in the elections for the Yishuv (the Jewish Council), over 10% if one considers the vote in the cities.

One episode – limited but significant – showed the potential for the development of class unity during a strike. Two-hundred Jewish workers at the Nesher cement factory in Haifa were joined in a strike by 80 Egyptian co-workers, putting forward their own demands, with the latter having reduced rights and being paid half as much.

After a two-month-long strike, the boss conceded some of the Jewish workers’ demands. The deal was voted down by them, 170 to 30 (defying their own union’s position) and they vowed to continue the strike until the demands of their Egyptian comrades were fully met.

The danger that such an example could become contagious prompted the Histadrut leadership to put pressure on the British colonial administration, which clamped down by deporting all 80 Egyptian workers.

A propensity for workers’ unity in the struggle emerged several times in the decade 1925-35. We should mention the bakers’ strike, the struggles of the Haifa port workers and the railway workers, the strike of the public transport and taxi drivers in 1931. In 1935 we see the important struggle of the workers of the Iraqi Oil Company and the Haifa refinery.

During those years, the PCP organised trade unions independently from the Histadrut and gained important bases of support in many areas among the majority of Arab workers, and many Jewish workers. Their successes forced the Zionists to change tactics and promote Arab trade unions federated with the Zionist ones, to counter the influence of the Communists.

The enormous potential represented by the growth of the PCP, however, was wasted by the consequences of the Stalinist degeneration of the USSR. The Soviet bureaucracy under Stalin converted the Communist International into a mere tool to pursue its diplomatic interests. This meant abandoning the correct revolutionary policy of class unity, by pandering towards Arab nationalism during the Great Palestinian Revolt of 1936-39, resulting in the loss of most of the PCP support among Jewish workers.

During the Second World War the PCP suffered an even bigger blow by Moscow’s u-turn in favour of war collaboration with British imperialism, which undermined the party’s base among the Palestinian working class, before receiving a death blow in 1948 by the USSR’s decision to support the formation of Israel.

The reactionary role of the Palestinian elite

Among the Palestinians, the emerging nationalist camp was hegemonized by the elite families, which had supplied municipal officials, judges, police officers, religious officials, and civil servants to the Ottoman administration and later to the British colonial authority. They emerged as the Palestinians’ national leadership. A vast gulf, however, separated the elite from the largely poor and illiterate masses.

The struggle for supremacy between the Husayni and the Nashashibi clans, in the mid-1930s, led to the formation of two rival Arab nationalist parties. The Nashashibi-led National Defence Party was countered by the more extremely nationalist Palestine Arab Party. However, the Husayni and the Nashashibi’s allegiance to Arab nationalism did not prevent both from populating the long list of those who had secretly sold land to the Zionists.

The Palestine Arab Party radicalised its positions along anti-Semitic lines. Many Arab nationalists (including the future Egyptian president Anwar Sadat) openly sympathised with fascism and Nazism. Amin al-Husayni’s words of support for Hitler in a speech to the German Consul in Jerusalem are emblematic: “the Muslims inside and outside Palestine welcome the new regime of Germany and hope for the extension of the fascist anti-democratic, governmental system to other countries.”

Armed Arab nationalist groups developed. The “Black Hand”, led by Sheikh Izz al-Din al-Qassam, carried out sparse attacks against Jewish settlers since 1931. Al-Qassam was killed by British forces in an ambush on 21st November 1935, thus becoming a rallying figure for Arab nationalism.

The pace of Jewish immigration had further increased in the course of the 1930s. Between 1931 and 1934, a prolonged drought hit Palestine. In 1932, agricultural production plummeted by between 30 and 75 percent, depending on the crops and areas affected. This impoverished Palestinian villages and caused overcrowding in the slums around Jaffa and Haifa.

A financial crisis also hit Palestine, caused by the repercussions of the Abyssinian situation, which led to the bankruptcy of many companies. The combination of these factors exacerbated the position of the Palestinian masses.

The Great Palestinian Revolt of 1936-39

The clashes of 1921 and 1929, although violent and bloody, had only directly affected a small layer of the Arab and Jewish population.

In April 1936, however, the Palestinian revolt spread on a mass basis from the cities, where “National Committees” were spontaneously formed on the initiative of radicalised youth, the shababs. The traditional leaders were reluctant to clash head-on with the British authorities. It was not until 25th April that the Arab Higher Committee was formed to lead the revolt under the leadership of the Husayni.

The Revolt was characterised by a six-month-long Arab general strike and a permanent semi-insurrectionary struggle and armed guerrilla in the countryside (from mid-May to mid-October).

The different scale of this revolt was noted by Ben-Gurion himself, who wrote that the Arabs were “fighting against dispossession… The Arab is fighting a war that cannot be ignored. He goes out on strike, he is killed, he makes great sacrifices.” He also stated on May 19, 1936: [the Arabs] “see… exactly the opposite of what we see. It doesn’t matter whether or not their view is correct… They see immigration on a giant scale… they see the Jews fortifying themselves economically… They see the best lands passing into our hands. They see England identify with Zionism.”

The Zionists (the Histadrut trade union at the forefront) pursued an aggressive strike-breaking policy aimed at replacing Palestinian with Jewish labourers on a company-by-company basis.

In 1937, the secretary of the trade union federation in Jaffa, explained the Zionists’ position thus: “The Histadrut’s fundamental aim is ‘the conquest of labor.’… No matter how many Arabs are unemployed, they have no right to take any job which a possible immigrant might occupy. No Arab has the right to work in Jewish undertakings. If Arabs can be displaced in other work, too… that is good.” (Quoted in Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, p. 122.)

For months, the British authorities had no other alternative than waiting for the strength of the insurrection to wane. It was only on 7th September that martial law was proclaimed and a curfew imposed. 20,000 soldiers were shipped in from Britain and Egypt, aided by 2,700 additional Jewish policemen. A counter-insurgency operation began, which prompted the Arab leaders to call off the strike by 10th October, hoping it would lead to a negotiated way out.

The British government convened a Royal Commission led by Lord Peel, to carry out an inquiry and determine the terms for a settlement of the Palestinian-Zionist conflict. The 404-page-long Peel Report, published on 7th July 1937, recommended the partition of Palestine: 20 percent of the territory to the Jewish Authority; Jerusalem and a corridor to Jaffa under British administration, as well as the coastal cities with a mixed population; the rest would be joining Transjordan and form a single Arab state. Corollary to the proposal was the forced transfer of 225,000 Palestinians and 1,250 Jews.

The Zionist leaders Weizmann and Ben-Gurion regarded the Peel Report as a stepping stone to further expansion. Weizmann commented: “The Jews would be fools not to accept it, even if [the land they were allocated] were the size of a tablecloth.” The report was therefore accepted by the Zionists, while it was rejected by the Arab Higher Committee.

Second phase of the Revolt

In September 1937 the Revolt resumed with vigour, but the Arab Higher Committee was torn apart by a violent feud that arose from the Husayni’s attempt to assassinate the leader of the opposing clan, in July 1937. “Streams of blood are now dividing the two factions,” noted Elias Sasson, a senior official of the Jewish Agency, in April 1939.

The insurrection continued in a spiral of clashes and repression. The Arab Higher Committee was outlawed and 200 of its leaders were arrested, many of them hanged, while others flew.

The “Peel Report” spurred the Jewish right-wing revisionist party (those demanding a revision of the British Mandate) to launch a terrorist campaign against ordinary Palestinians. Multiple bomb attacks by the Irgun Zwai Leumi hit Palestinian civilians at bus stations and markets, killing and maiming hundreds.

The Palestinian armed groups acted without a centralised command. Many of them, without perspectives, unfortunately turned into criminal gangs who plundered the Palestinian peasants, quickly alienating their support. This situation decisively undermined the prospects of the Revolt.

The Revolt continued until May 1939, involving at its peak, in the autumn of 1938, about 20,000 Palestinian fighters. On the eve of the Second World War, what had been the most serious and protracted Arab revolt against British occupation ended with a death toll of many thousands and a de facto defeat.

The Second World War and the Holocaust

The defeat of the Revolt sanctioned a sharp turn in British imperialism’s policy. The British feared a new outbreak of Arab revolt when forces had to be made available for other fronts. Moreover, British imperialism did not want to antagonise the Arab bourgeoisie, in an attempt to prevent their collaboration with the Nazis.

The White Paper drafted by the colonial administration (published on 17th May 1939) introduced for the first time a cap on Jewish immigration (a maximum limit of 75,000 over the following five years) and severe restrictions on the purchase of land by Jews. It also set the prospect within ten years of the creation of an independent state governed according to the majority principle.

This change of course did not gain British imperialism more Arab support. However it did undermine Britain’s close relationship with the Zionist leadership. The British u-turn (at the very moment when fears of the Nazi anti-Semitic policy were rising) was experienced as a betrayal by the Zionists.

The British authorities had helped the Haganah’s transition towards “aggressive defence” against the Palestinians. In May 1938, the Haganah set up “field companies” to apply counterinsurgency tactics in the countryside. One month later, Special Night Squads were created, with the task of terrorising during the night Arab neighbourhoods and villages that were supporting the Revolt.

These same tactics would be used on a much higher scale a decade later by the Zionists, to ensure Palestinians fled their villages and homes in terror, in the run-up to the establishment of Israel.

At the beginning of 1939, three secret units known as Pe’luot meyuchadot (“special operations”) were created with the task of carrying out reprisals against Arab villages and guerrilla units, but also of carrying out attacks on British installations and eliminating informers. These units were put under the direct command of David Ben-Gurion.

The first reports of mass deportations of Jews by the Nazis began to filter through, along with the Jewish European refugees, producing a huge psychological impact on the Jewish population of the diaspora (especially in the US) who found intolerable the odious restrictions imposed by the British authorities on immigration.

The attitude of the Zionist leadership towards the Nazi threat, however, was characterised by cynicism. In December 1938, a month after the Nazi pogrom later known as Kristallnacht, Ben-Gurion stated: “If I knew it was possible to save all the [Jewish] children of Germany by their transfer to England and only half of them by transferring them to Eretz-Yisrael, I would choose the latter—because we are faced not only with the accounting of these children but also with the historical accounting of the Jewish People.”

In December 1942, he again commented: “The catastrophe of European Jewry is not, in a direct manner, my business…” (Quoted in Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, p. 162).

The Zionist leadership used the desperation of the Jews fleeing Europe to strengthen international support for Zionism and blatantly defy the blockade on immigration imposed by the British authorities, who were determined to clamp down on illegal immigration at all costs.

Part of the Zionist right-wing, however, rejected any collaboration with the British. In November 1944, the Lohamei Herut Israel (LEHI), “Fighters for the Freedom of Israel” (also known as the Stern gang) assassinated in Cairo the British minister resident in the Middle East, Lord Moyne.

A series of boats filled with refugees were set up in open defiance of the British prohibition, provoking a tug-of-war with the Mandate authorities who had decided to block all attempts and deport thousands of refugees to concentration camps on Mauritius and Cyprus. The refugees were pawns, trapped in a cynical power game which led to multiple tragedies.

In November 1940, the Haganah blew up the Patria, a ship anchored in Haifa loaded with 1,700 immigrants awaiting deportation to Mauritius, causing 252 deaths. Another ship, the Struma, with 769 refugees on board, sank on 25th February 1942 in the Black Sea after the British authorities had vetoed their transfer (all-but one were killed).

Very few Jewish refugees escaped to Palestine during the War, while the Nazis were exterminating six million Jews in Europe, along with millions of Slavs, Roma, communists and anti-fascists of different nationality, religion and political orientation.

To be continued in Part II: From the Nakba to the Intifada and the Oslo Accords

Pre-order your copy of ‘Israel-Palestine: A Revolutionary Way Forward’ from wellredbooks.co.uk.