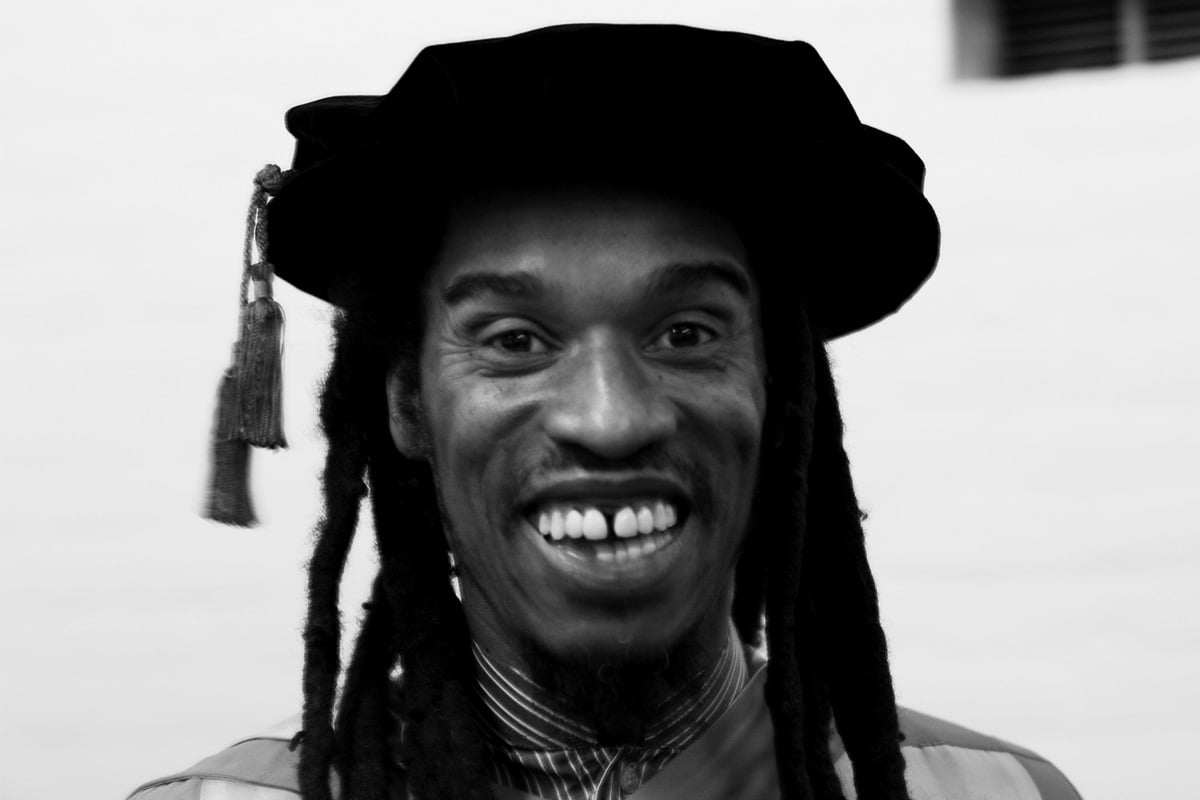

Benjamin Zephaniah, an outstanding figure in British poetry, died yesterday, 7 December. Over the years, his profound, lively, and deeply personal verses resonated with millions, in Britain and around the world.

His work was in the first place political, aimed towards raising consciousness amongst the oppressed and exploited. For Zephaniah, the purpose of art was not to win awards or climb the ranks of the literati, but to lay bare the truth of society for all to see and understand.

He was unapologetically opposed to racism and oppression in all its forms. And he advocated unity across racial and national lines against the system that torments all the poor and oppressed. As he explained: “The oppressors know how to unite; the oppressed must unite.”

As a result of this bold stance, the press subjected him to a campaign of vilification. But he never buckled to these pressures. And despite the plaudits he later received, Zephaniah remained true to his principles, notably rejecting the offer of an honour from the Queen.

Social ferment

Zephaniah was born in Birmingham to Caribbean parents during a period of deep social instability.

Due to a dearth of jobs, as well as constant police harassment, many young black people were pushed into petty crime to make ends meet. On top of this, the racist, far-right National Front was carrying out attacks against minorities, with the complicity of the authorities.

After a short prison sentence for burglary, Zephaniah moved to London, in his words, “to escape the unemployment, the ‘thug life’, and the West Midlands Police Force”. However, the situation he faced in London wasn’t much better.

In the late ‘70s, unemployment – particularly amongst young people – was beginning to soar. By the 1980s, Thatcher was declaring war on the trade unions and deindustrialising the country.

This wreaked havoc on working-class communities, galvanising the labour movement and fuelling anti-establishment sentiment. Immense ferment was boiling over, and society was polarising sharply.

Art as activism

This hatred towards the establishment found an expression in cultural and artistic spheres. Zephaniah and others, such as Linton Kwesi Johnson, gave another dimension to this movement through innovative and compelling dub poetry – rhythmic performance poetry based on Jamaican dub music.

Through his poems, Zephaniah was able to concentrate his life experiences dealing with poverty, racism, and his Rastafarian lifestyle into ordinary and engaging language that could be grasped by anyone who cared to read or listen.

Although he used a simple vocabulary set, he was not naive or amateur as a poet. His artistic depth was well understood in critical circles. His writings were not a stream of consciousness, but were carefully considered. He did not try to water down the content of his ideas. Rather, he wrote serious poetry, packing complex thoughts, feelings, and ideas into simple stanzas that could be grasped by anyone.

Zephaniah saw his art in the first place as activism. His poems aimed to raise consciousness and unite people together against their common oppressors.

In contrast to the typical intellectual, who more often than not operates in a world divorced from ordinary people, Zephaniah’s view of art was active and social.

Not only would he regularly perform his poetry live, but he would also have conversations with those who came to his gigs, discussing ideas with them. Many of his poems were borne out of such interactions.

He wanted to gain an all-sided view of society, in order to understand the common thread that unites people, with the goal of changing the world.

United struggle

When you first read his poetry, the most striking thing is his Rastafarian style – an important feature of his work. By strictly being himself, without pretensions or superfluities, Zephaniah emphasised that the author behind the stanzas is a real individual. He was a black, Rastapharian man, and he had no desire to hide this.

In stark contrast to the postmodern ideas that were already circulating in intellectual milieus around this time, Zephaniah did not limit his art solely to his own individuality.

Rather, he broke down the wall between “you” and “I”. The point he hammers home in his writings is that “I” am not very different from “you”. My thoughts, feelings, and ideas are a product of the same society that you also live in.

We may experience different things, in different ways, but you and I are not separated by an impenetrable barrier. I may be a black man, and you a white man, or whatever you happen to be, but we are part of the same society with the same struggle – and we need to unite together in this.

His outlook is aptly summarised by an eight-line poem, U.N. (United Neighbours):

“Me is a simple Jamaican man / From Jamaica in de Caribbean / Me look like an African / Because Africa is me Motherlan.

Me neighbour is a European / Born an bred in Engerlan / An we juss cannot understan / Why nations cannot live as wan.”

It is our ruling classes who are warring with one another, he is saying, and who goad us to war amongst ourselves.

The title of the poem, United Neighbours, is the logical conclusion: “Let’s unite and do something about it.”

This active, unifying outlook runs throughout Zephaniah’s body of work.

Racism and violence

Although he regularly makes reference to his experience as a black man, it is abundantly clear from his work that he was not a Black Nationalist.

In his poem, The Race Industry, he attacks those cynical careerists (“coconuts”: brown on the outside, white on the inside) who use the black colour of their skin to climb the social ladder and profit from the same system that forces the majority of black people into destitution:

“We despairing, they careering. / […] / They will do anything for the Mayor / […] / In suits they dither in fear of anarchy. / They take our sufferings and earn a salary. / […] / Without Black suffering they’d have no jobs. / Without our dead they’d have no office. / Without our tears they’d have no drink. / If they stopped sucking we could get justice. / The coconuts are getting paid. / Men, women and Brixton are being betrayed.”

While he wanted an end to racial violence, advocating peace, he understood that pacifism was a trap. His poem, Self Defence, highlights this. This should echo with us today, in the wake of events such as the recent far-right riots in Dublin:

“We only want peace but / Here comes de beast / Ignoring de truths and de facts, / Attacking de weak out on de streets / And we nar tolerate dat, / Self defence is no offence and / We can’t wait fe no one else.”

He placed no illusions in the sham of parliamentary processes, as shown in his three-part Acts of Parliament. And in The War Process, he shows the UN in its true colours – as a bankrupt talking shop:

“My Rwandan friend said, ‘At least they have ceasefires in Bosnia.’ My Bosnian friend said, / ‘What is a ceasefire, / By the way?’

Outspoken and vilified

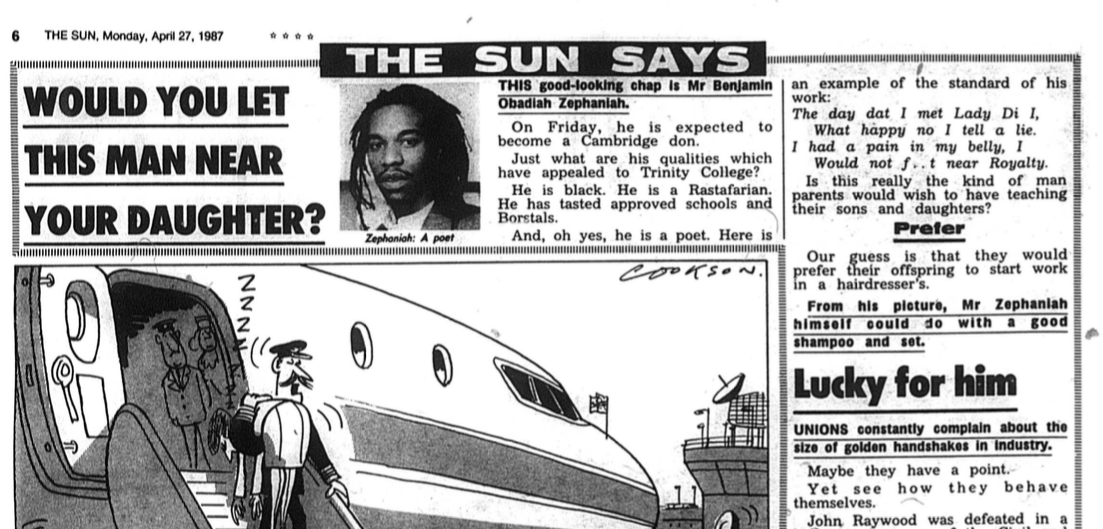

While becoming very popular amongst ordinary people, he was initially vilified by the establishment for his outspokenness and for the rawness of his style.

The Sun, for example, published a hit piece on him with the headline: “Would you let this man near your daughter?” With his dreadlocks on display, they ran the caption: “From his picture, Mr Zephaniah himself could do with a good shampoo and set.”

Instead of toeing the line, ‘cleaning up’, and becoming a more ‘respectable’ poet, Zephaniah pointed the finger back at this racist, sexist, right-wing rag. In his poem, The SUN, he writes:

“Black people rob / Women should cook / And every poet is a crook, / I am told – so I don’t need to look, / It’s easy in The SUN.”

And he adds: “But aren’t newspapers all the same?”

Zephaniah highlights how all the big newspapers carry out the same function: to serve up the poisonous propaganda of the ruling class. And some, unlike The Sun, do this more subtly than others.

It is the system that breeds and needs racism – a system run and enforced by our common class enemy, regardless of skin colour.

And Zephaniah, in this respect, called for our solidarity to be based on our position in society, not our racial identity.

Telling the truth

In obituaries in the mainstream press, journalists and editors have emphasised Zephaniah’s ‘safer’ and more ‘respectable’ material. As Lenin once explained:

“It has always been the case in history that after the death of revolutionary leaders who were popular among the oppressed classes, their enemies have attempted to appropriate their names so as to deceive the oppressed classes.”

This is not only true of certain popular revolutionary leaders, but also of those great artists with undeniable genius who are able to forge a genuine connection with the poor and the oppressed.

Zephaniah’s art, of course, had many sides to it. Like every real living person, he did not fit a one-dimensional typecast. But running though his entire corpus is an unflinchingly truthful presentation of capitalist society: rotten to the core, running off the division and exploitation of the vast majority.

His aim was to tell the truth about the world, in all its aspects. He did not make art to win poetry awards, but to expose the sick society that we live in, and to galvanise people into action. As he wrote in his four-line poem, Art:

“Poems are read my love / Sad songs are blue / Love songs are sweet my love / And all great art is true.”