The speculative craze around NFTs has reached feverish proportions recently.

Whilst NFTs can be used for anything digital, the vast majority of sales have involved digital art. As a consequence, we are subject to the absurd spectacle of mostly trivial and shallow ‘artworks’ being traded and sold for obscene amounts of money.

An ever-increasing amount of celebrities and corporations are rushing to get in on the world of unregulated financial speculation in the art market. Recent NFT enthusiasts include former footballer John Terry, and even established multi-millionaire artists such as Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons.

What we are witnessing is not in fact the future of art, as some are eager to tell us, but the logical conclusion of the capitalist art market – part of the commodification of art and culture, where anything and everything can be sold for a profit.

NFTs represent a cynical attempt to profit from art that contains little-to-no genuine artistic merit; and which, in some cases, does not even require human labour to produce and reproduce.

Tokens, certificates, and ledgers

NFTs are not the assets or art themselves, but a unique digital ‘non-fungible token’ that is stored on the ‘blockchain’.

The blockchain is a piece of digital technology that publicly records transactions in such a way that they cannot be forged. This same technology lies behind cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin.

When one buys an NFT, therefore, one is really buying an entry onto a global ledger, which indelibly records that this specific token was purchased by yourself.

These tokens, then, are intended to provide the buyer with a digital certificate of ownership of the asset – although the NFT does not confer control over the asset in any way.

Capitalist contradictions

The digital world is characterised by superabundance. After all, images, sound files, and other information can effectively be copied millions of times for free.

This abundance flies in the face of attempts to commodify digital goods, standing in contradiction to capitalist property relations.

Given that they are infinitely replicable at almost no cost, the socially necessary (average) labour time required to produce digital goods en masse will tend towards zero. According to the law of value, as Marx explained, this means that the value of such goods will approach zero.

A proliferation of information – under market forces and free competition, with no real physical restrictions on supply – would therefore tend to push prices down to zero. Information, in other words, “wants to be free”.

As a result, capitalists have spent years trying to find a way to force the digital economy into the straightjacket of private property.

Before the invention of NFTs, no one would think to claim that they own this particular image file on this particular hard drive, since it could be perfectly copied at will, ad infinitum.

Such a situation represents an advance of the productive forces to the point where private property in any digital information is redundant and meaningless. In principle, everyone with a computer or smartphone can access the same information as everyone else.

In essence, therefore, NFTs are an attempt to introduce artificial scarcity – and thus private property – into the digital world. As such, they represent the fetter of capitalism holding back the productive forces, and societal progress more broadly.

Investor assets

The prospect of opening up the vast field of digital artwork to private ownership, and thus to the capitalist market, is enabling NFTs to trade for astronomical prices.

Capitalists have long-recognised the potential profits from investing in art. For example, in 2017, Saudi Prince Badr bin Abdullah paid $450 million for Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, making this the most expensive painting ever sold – despite its highly disputed authenticity.

Gullible buyers of assets with NFT attachments are hoping that these digital tokens are valuable in their own right. Furthermore, they hope that these will appreciate in value over time, due to their unique one-off nature, much in the same way that one-of-a-kind Picasso or Monet artworks now sell for tens – or even hundreds – of millions of dollars.

Except, in the case of NFTs, the object of value is the token itself; the artwork is in fact secondary!

Unique vs abundant

As NFTs are bought and sold with cryptocurrency, the hope is also that the artworks will appreciate in value alongside the cryptocurrency market – a highly unstable and volatile market in its own right, as recent events have demonstrated.

Again, the problem is that in the case of digital artworks, there is nothing stopping the instantaneous copying and distribution that can take place with the click of a mouse. A jpeg file, video file, or any form of digital file is ultimately just data. And identical copies of these can be made instantaneously by anyone with a computer and access to the internet.

The existence of an NFT that supposedly offers a claim to the ‘original’ does not change this fact.

This is the fundamental difference between a physical work of art, which is indeed unique and irreplicable, and digital art, which is not.

Lost files

Furthermore the soundness of the entire NFT system has been called into question several times before.

NFTs rely on traditional URLs and hyperlinks to direct the purchaser to the artwork itself. And these hyperlinks can die for many different reasons, including if the gateway operator goes bust.

There are already examples of NFTs that have temporarily been linked to files which won’t load.

A physical artwork can be kept in one’s house – or for wealthy investors, in one’s bank vault. But buyers of NFTs have to hope that the digital artwork continues to be hosted online, remaining available somewhere on the internet.

It is possible that in a few years, many NFT buyers will be holders of tokens that link to dead or lost files. In that case, will they still be able to sell an NFT which refers to a non-existent artwork? Or even to an artwork no one has seen or can verify ever existed?

This is akin to attempting to sell a painting that you had lost 20 years ago!

‘Crooks and swindlers’

The motivation behind the buying and selling of NFTs has nothing to do with the quality of the art involved. This much is clear from even a cursory glance at the type of ‘artwork’ available for sale at auctions and on the internet.

The vast majority of it is childish, crass, disgusting, and says nothing meaningful at all. The artist David Hockney described them as “silly little things” for “crooks and swindlers”.

It is of course true that some degree of technical ability is needed to produce these artworks. But that is entirely beside the point.

They are in essence commodities – designed and produced purely for profit-making and speculation.

In fact, the main takeaway from an NFT transaction is the sale and purchase of it. The ownership of the art is what’s important, not whether it is appreciated or not. The intention for the sellers was never to produce any meaningful or skillful artwork.

Market irrationality

Many artists are in fact turning to NFT sales not to enhance the artistic value of what they are producing, but simply as another source of revenue.

DJ Steve Aoki has in fact boasted that he’s made more money from selling NFTs than from 10 years of music industry advances.

The most expensive NFT ever sold was Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days, which was sold by Christie’s for $69 million in March 2021.

This artwork is a collage of 5000 individual digital artworks that Beeple had produced over the course of as many days. The piece has been roundly lambasted by critics, and not just for its obscene price tag. Jason Farago in The Times described it as a “violent erasure of human values”, reliant on “puerile amusements.”

The final sale price of Beeple’s work makes it more expensive than several paintings by Picasso and Monet. Does this mean that Beeple is in fact a superior artist? Or that clever art investors see Beeple’s work as more valuable, both in a financial and a creative sense?

Hardly. It is nothing more than a reflection of the irrationality of the art market and of capitalism as a whole.

Taking off

It does not matter that NFTs have no inherent value in themselves, or that the art connected to NFTs is bad. They have nevertheless taken the art market by storm, since, for the time being at least, they provide a way to monetise and sell digital art.

Even established art galleries that deal in digital art have struggled in the past to attract investment in digital-only work. Attempts were made at issuing paper certificates and USB drives as vessels for these works, but little progress was made.

But now, due to the speculative fever associated with cryptocurrencies, NFTs, and digital art have taken off.

Speculative bubbles

Karl Marx explained that capitalism is an economic system in which commodity production and exchange dominates and becomes generalised.

This means that the vast majority of productive activity in capitalist society is no longer for personal consumption or need, but takes the form of commodities – goods and services produced for exchange and profit.

Under capitalism, Marx explained, society develops a ‘commodity fetish’, meaning that quite literally anything can and will be sold – including things with no inherent value. The explosion of NFTs are a perfect example of this.

Looking to make an easy, short-term profit, speculating capitalists attempt to avoid the hard effort and grubby activity of real production. Instead, they hope to invest in something that will appreciate in value simply through supply and demand; by ‘buying cheap and selling dear’.

Ever since the inception of capitalism, there has been a tendency to fulfil this need by investing in crazes – and particularly in things that are unique or unreproducible.

After all, to make money from your money, you do not want to invest in something that can be reproduced at will. You must instead find something that everyone agrees is a one-off; a ‘must have’ item.

For that reason, art has often played this role, regardless of its artistic quality. What matters is that the artwork is famous; much sought after for being an original piece or a rare find.

In fact, an artwork can become famous precisely because it is bad or controversial. Such a piece – so long as one can definitively point to the original – is perfect for speculative investment, since everyone will know that you own the original of this (in)famous artwork.

In this respect, there is nothing new about NFTs as a form of speculation in the art market. What marks NFTs out is simply the fact that they have been designed to artificially generate this desired scarcity, where it should not apply.

The millions of pounds being spent by investors on NFTs – and the atrocious artworks attached to them – are therefore another symptom of the degeneracy of the capitalist system.

Faced with deep economic crisis and uncertainty, the capitalists are turning away from investing in real production, and are instead inflating one speculative bubble after another: be it stocks and shares, the property market, or any other get-rich-quick scheme that is in vogue.

Cryptocurrencies and NFTs are only the latest example of this insanity and anarchy.

Degeneration of art

NFTs might be the latest craze in the speculative and profit-driven art market. But the conditions for these recent developments have been prepared for decades. For a long time now, mainstream art has been degenerating into triviality, becoming subordinated to money-making and the market.

The British artist Damien Hirst has become one of the world’s richest living artists by embracing the market, and effectively operating as a business.

Bursting onto the scene in the 1990s, Hirst’s works were simple-minded, designed to shock and disgust more than anything else. He even bragged about not producing the majority of his own work.

His most famous pieces include The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (a shark preserved in formaldehyde) and The Golden Calf (a calf preserved in formaldehyde).

For many, Hirst’s artwork is a prime example of the commercialisation of art, as rich investors flock to buy the latest monstrous creation that he adds his signature to.

In a scathing assessment of Hirst’s work, Australian art critic Robert Hughes said the following:

“This skill at manipulation is his real success as an artist. He has manoeuvred himself into the sweet spot where wannabe collectors, no matter how dumb (indeed, the dumber the better), feel somehow ignorable without a Hirst or two.”

The gap between Hirst’s skill and talent as an artist, on one side, and his financial success, on the other, is vast. However, Hirst’s lack of talent is irrelevant when it comes to the demands of the art market under capitalism.

One can make the exact same assessment of the world of digital art and NFTs. In fact, Beeple – who is currently the most successful (and wealthiest) digital artist to make use of NFTs – makes this very point himself.

Beeple had already gathered a following of over two million people on Instagram when the NFT buzz began to take hold in around October 2020. He then thought, in his own words: “I’m more popular than all of these people; and if they’re making this much then I would probably make a fucking shitload of money.”

Winckleman (Beeple’s real name) has stated that he sees his buyers “as investors more than collectors”. This viewpoint is not uncommon for the art market – although it is certainly not common to publicly declare it.

In fact, Beeple has very openly questioned the real value of his art, comparing it to the type of work available on the established art market: “If you look at fine art, most people would say the same thing – who paid for this?”

In a market where a Banksy print (appropriately named ‘Morons’) can be partially burnt and then re-sold as an NFT for £274,000, it is hard to argue with this sentiment.

Beeple himself has been producing digital artwork for over ten years – well before the NFT trend started. From this perspective, then, one can hardly blame him for jumping on the bandwagon and successfully convincing rich capitalists to invest vast sums of money in his work.

Beeple might be the latest trailblazer. But he stands in a long tradition of commercial artists – quacks and charlatans – who prioritise profit above all else.

In many ways, the explosion in demand for NFTs and digital art was only the next logical step for an art market that, like Oscar Wilde’s cynic, understands ‘the price of everything and the value of nothing’.

Art and revolution

Great art is one of the crowning achievements of human civilization. It should be common property, freely accessible for all to enjoy.

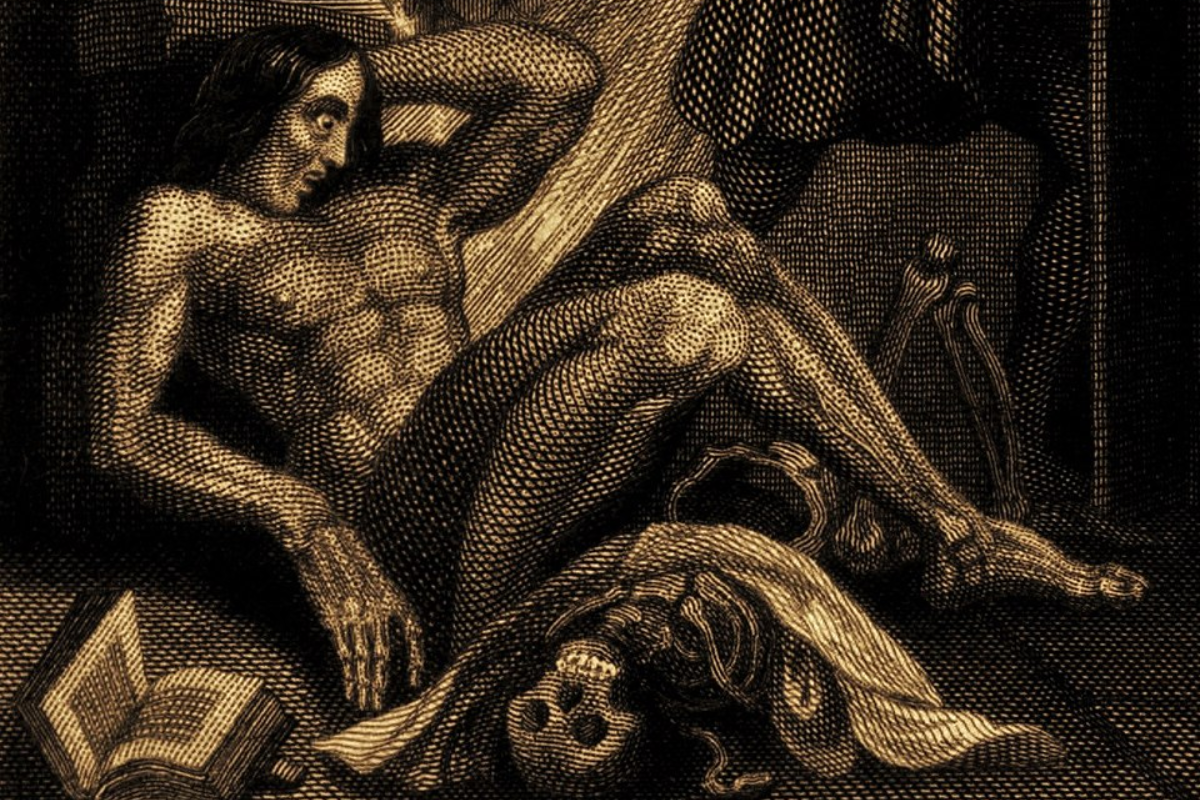

But the forces of the capitalist system have twisted and corrupted art, turning it into a vapid and soulless commodity, flogged to the highest bidder.

Art has become alien and repulsive to ordinary people, who look on amazed as vulgar, gullible, wealthy investors buy up dead animals in vats of formaldehyde and bored ape NFTs – all in the desperate hope that someone else will eventually pay even more money for them.

In order for art to be freed from the economic forces that have debased and enslaved it, turning it into a speculative commodity, society must be freed from the domination of capitalism itself.

Only when all of humanity has control over its own existence – under a socialist system of collective ownership – will art be able to escape the shackles of private property and the market.

Only then will men and women across the world finally have the means to fulfil their full creative potential, which is currently stifled by the drudgery and toil of capitalist exploitation and wage slavery.

Only under these conditions will we be able to celebrate true art and human creativity, consigning the likes of Hirst, Beeple, and the art market to the history books and museums.

Only through revolution and the fundamental transformation of society will we collectively reach artistic heights only previously achieved by individual geniuses.

It is therefore the duty of all art to fight against the system which is hostile to it: the capitalist system.

In the words of Leon Trotsky and André Breton: “The independence of art – for the revolution. The revolution – for the complete liberation of art!”