To help readers with the fundamentals of Marxism, and to reply to the biggest myths surrounding Marxist ideas, we provide here a series of answers to the most frequently asked questions about socialism, communism, and revolution.

The aim is to arm ourselves with the arguments needed to confidently defend Marxist ideas when discussing with others – and, in turn, to help equip ourselves with the necessary tools in the fight for revolutionary change.

The following key articles also outline the fundamental ideas of Marxism.

Frequently asked questions

Click on the links below to skip straight to the questions you’re interested in finding answers to.

Socialism sounds great – but what about human nature? Aren’t people inherently greedy and selfish?

Hasn’t socialism been tried and failed?

Why do we need a revolution? Can’t we just reform our way to socialism?

Isn’t capitalism more efficient than a planned economy?

Without the profit motive, wouldn’t innovation just grind to a halt?

Are Marxists in favour of violence?

Is democracy compatible with socialism?

Is it possible to have a revolution when all the mainstream media is against us?

Do we need a revolutionary party?

Is it possible to have socialism without destroying the planet?

Was the 1917 October Revolution a “coup”?

Wouldn’t everyone be lazy if we’re “all paid the same”?

Do Marxists want to ban religion?

Socialism sounds great – but what about human nature? Aren’t people inherently greedy and selfish?

Many people seem prepared to accept that capitalism is unable to solve problems such as unemployment, homelessness, hunger and war. Many would agree in theory that, if the vast resources of the world were used rationally in order to meet human needs rather than for the profits of a few billionaires, everybody on the planet could be guaranteed a decent standard of living.

Yet in order to maintain a system in which eight individuals control as much wealth as half the world’s population combined, we’re told by the ruling class that the current state of affairs is natural, since it is in humanity’s “nature” to be greedy and selfish. Any attempt to implement a more egalitarian system, we are lectured, is therefore doomed to failure – so don’t even think about it!

On the surface, this can appear convincing, particularly given the failures of Stalinism in the 20th Century. But what really is our “human nature”? The further you look back in history, the more difficult it becomes to talk about a universal set of values that applies to all humans at all times.

For example, is it in our “nature” to keep other humans as slaves? The ruling classes in ancient Rome and Greece would have argued so but clearly this is not the case.

In fact, anatomically modern humans have existed for about 200,000 years with signs of hominid life going back as far as 6 -7 million years at least. The use of tools dates from as long ago as three million years. For the vast bulk of our history, we lived in primitive communist tribes, where there was no rich or poor, no exploiting and exploited class, no money, no police or prisons.The tools and assets of a tribe belonged to every member in common. As the productivity of labour was so low, it was impossible for anyone to live by exploiting the surplus labour of others. People put the tribe before themselves.

Class societies, i.e. systems based on the exploitation of the majority by a minority, have only existed for the last 6 – 12,000 years, since the development of agricultural farming rather than simple horticulture. The first clear evidence of a fully formed class-structured society appeared only about 5,500 years ago with the Sumerian civilisation and the start of the Bronze age.

It is within these societies that a handful of people – the class of exploiters – are forced by their position as rulers to act selfishly and greedily. If they did not act ruthlessly and in their own interest, they would cease to enjoy their positions of power, as more ruthless individuals would challenge and out-compete them.

Therefore under capitalism, it is the outlook of the ruling class – which is necessarily selfish and greedy – which we are now told is applicable to all humans everywhere and for all times – i.e. as part of our inherent “nature”.

However this is obviously not true, as evidenced by the millions of acts of solidarity and kindness seen each and every day across the world, from firefighters risking their lives to save others, to ordinary people giving up their time and money to help strangers in need.

What is certainty not “natural” is for nearly all the means of production (including resources, industry and knowledge) to be privately owned and controlled by a tiny minority of the population. By setting industry free from the constraints of production for profit, we could easily produce enough so that everyone could take freely what they need and much more!

In a society of superabundance, the idea of accumulating more than you could use would become an absurdity, just as in an office with a well-stocked stationery cupboard, nobody stockpiles their own supplies of paper and pens. As Marx explained, it is material conditions that ultimately determine consciousness, not the other way around.

To those who agree with a socialist programme but think that “human nature” would hold us back, ask yourself – is it in your nature to want to ruthlessly exploit others? If not, then why everyone else?

Hasn’t socialism been tried and failed?

Einstein famously remarked, “insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”. So why, if socialism has been tried before and seemingly failed we are told, are Marxists still fighting for socialism? To answer this, it is important to understand what took place with the Soviet Union, and other countries calling themselves “socialist”.

Einstein famously remarked, “insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”. So why, if socialism has been tried before and seemingly failed we are told, are Marxists still fighting for socialism? To answer this, it is important to understand what took place with the Soviet Union, and other countries calling themselves “socialist”.

In 1917, the working class in Russia took power as the result of a mass revolutionary movement. The economy was taken out of the hands of the capitalists and landlords and society was run through the democratic control of the workers and poor peasants through workers councils (aka. “soviets”). Such measures represented the beginnings of a transition from capitalism towards socialism.

However, Lenin, Trotsky and the Bolsheviks never thought it would be possible to “build socialism in one country” but saw the Russian Revolution as the beginning of the World Revolution. As capitalism is a world system, socialism must be a world system.

This was soon confirmed in practice, when revolutions or revolutionary situations developed all across Europe, including in Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, France, Spain, and even Britain.

The failure of the working class to take power in these countries was not through lack of determination on their part. It was due to the lack of a revolutionary party, which would have been able to harness all the energy of the masses towards the conquest of power.

Hence the revolution in Russia was left isolated. Instead of being able to link up the vast resources of Russia, with the advanced industry of Europe, the Russian economy was left shattered after years of war.

As Marxists, we understand the ability to create a society free from the horrors of poverty, unemployment, hunger, and so on, is ultimately determined by the level of the productive forces (industry, agriculture, science, and technique), as well as their ownership and control.

Marx himself remarked: “A development of the productive forces is the absolutely necessary practical premise [of socialism], because without it want is generalised, and with want the struggle for necessities begins again, and that means that all the old crap must revive.”

The Russia of the early 1920s, after years of war, suffered catastrophic industrial and agricultural collapse. Want was indeed generalised. It was in this context, with millions of workers killed or exhausted by years of struggle, that participation in the soviets dried up and a layer of privileged bureaucrats began to usurp control.

Even by 1920, the number of state officials and bureaucrats numbered nearly 6 million. Most of these came from the privileged layers of the old Tsarist regime and it was this layer that Stalin came to power to represent.

Hence the totalitarian dictatorship, which was necessary to maintain the rule of the bureaucrats and destroy all links with the genuine traditions of the October revolution. As well as exterminating the Old Bolsheviks, all forms of workers’ democracy were crushed.

Without the democratic participation of the working class in planning and running society, the Soviet economy became suffocated by bureaucratic mismanagement and waste.

With the Soviet economy stagnating, a layer of the bureaucracy moved in the 1990s to restore capitalism (with themselves now as billionaires), as Trotsky predicted decades earlier in The Revolution Betrayed. Despite the horrors of the Stalinist regime, which genuine Marxists never supported, the restoration of capitalism was a disaster for the working class.

The task facing the working class today is to fight for genuine socialism not the crude distortion of the Stalinist regimes. It is Stalinism which ultimately failed not socialism.

For Marxists, workers’ democracy is the lifeblood of a socialist state. Most important of all is to understand that socialism in one country is not possible. That is why we are internationalists, that is why we fight for socialism not just here in Britain but throughout the world. This is the socialism we are fighting for – one which will sweep away the real failure of modern times: capitalism.

Why do we need a revolution? Can’t we just reform our way to socialism?

On the surface, this idea sounds appealing. Rather than the storms and stress of a revolution, wouldn’t it be much easier simply to win a majority in parliament and enact progressive reforms so that, slowly over time, we could transform capitalism into socialism?

It is true that in the past, the working class has won significant reforms in this way. The welfare state, the NHS, health and safety at work, the 8 hour day – all of these were won through struggle within the existing system. Is it not therefore strange to pose reform and revolution against each other, as if you can only have one or the other?

Genuine Marxists have never rejected the fight for reforms under capitalism. We do not say “let’s just wait until a revolution, when all our problems will be solved.” We will fight vigorously for any genuinely progressive reform that benefits the working class.

Marx pointed out that it is in the struggle for reforms under capitalism that the working class comes to realise its own strength. It is through such battles that workers develop their own class-consciousness, as well as organisations for the struggle – trade unions and political parties.

It is also through these struggles that workers come to learn first hand the limits of reforms under capitalism. This is particularly true in periods of crisis such as today.

In the past, under pressure from below, the ruling class would be prepared to grant certain reforms albeit always under pressure from the working class. Particularly when the economy was advancing, they could afford to make concessions, in order to keep the peace.

In fact the most significant reforms were conceded from the top, precisely to avert a revolution from below. Hence, for a time, the European ruling classes reconciled themselves to “welfare states”, which were also made possible by the massive expansion of the economy during the post-war boom.

The problem is that concessions won off the capitalists one day, will be taken back by them the next. This is particularly the case during a crisis, when in order to restore profitability, the capitalists will try to claw back from the working class the gains of the past. Rather than spend money on reforms, counter-reforms are then the order of the day.

Since the crisis of the 1970s, we have seen many of the progressive reforms of the post war period come under attack. The nationalised industries have been privatised, Pensions and pay attacked, council homes have been sold off and the NHS is in a severe crisis. All so the rich can continue to get richer at our expense.

These attacks can be reversed but, in a period of worldwide crisis, this would require breaking with capitalism. It is the requirements of the market (i.e. the interests of the bankers and billionaires) that dictate to governments; not the other way round, as the leaders of SYRIZA in Greece have painfully found out.

As Marxists, we understand that problems such as poverty, unemployment, crises and war are inevitable products of the system of capitalism. No amount of taxing the rich or borrowing money will change this. What is required is to take control of the key levers of the economy and plan their use democratically in order to meet people’s needs as part of a socialist plan of production under workers control and management.

To imagine that a socialist government could do this gradually – nationalise this industry one year, that bank the next year and so on, is to ignore the entire history of the class struggle. It is like imagining you could win a game of chess where only your own pieces can move. In reality, the other side attacks back, ferociously if necessary. No ruling class has ever given up its power and privileges without a fight.

So this is why we need a revolution – i.e. a mass movement of people across the world – to finally take power and control out of the hands of a tiny minority of capitalists and thereby secure deep and lasting reforms that will transform the globe.

Isn’t capitalism more efficient than a planned economy?

According to the apologists of capitalism, there’s nothing more efficient than the “free market.” But when it comes to providing for society’s needs, things like food or housing for example, the market economy is clearly and severely lacking.

According to the apologists of capitalism, there’s nothing more efficient than the “free market.” But when it comes to providing for society’s needs, things like food or housing for example, the market economy is clearly and severely lacking.

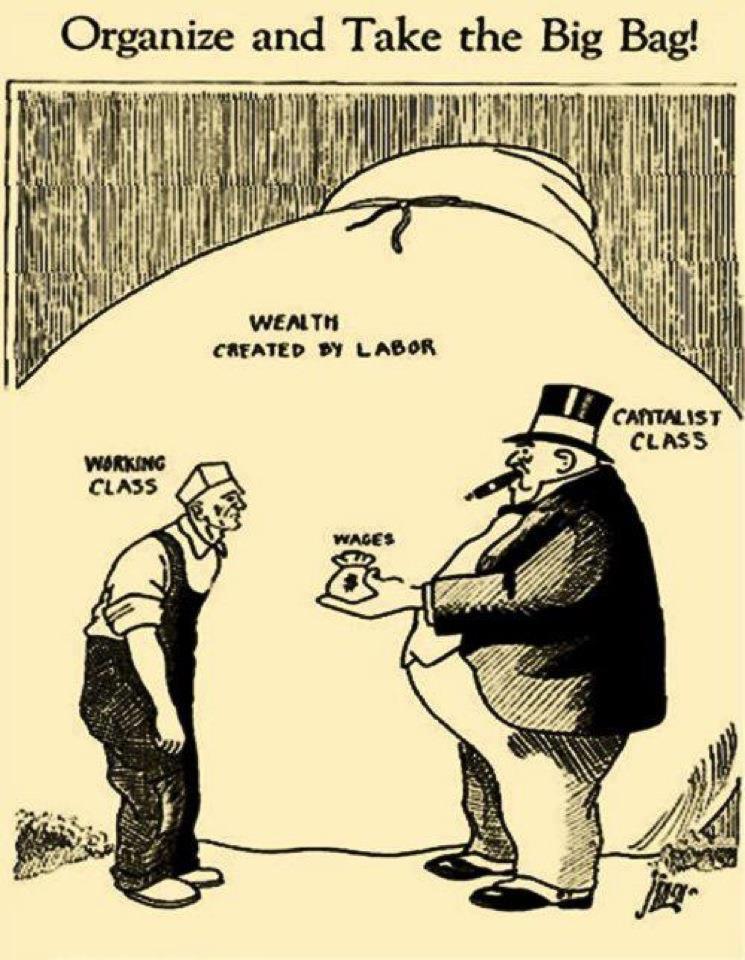

The one and only reason capitalists invest in production is to realise a profit. The social needs of society do not figure at all in their calculations. All that bothers them is how to most efficiently squeeze as much unpaid labour out of the working class in order to maximise their returns.

The inefficiency of capitalism is most starkly revealed through the chronic unemployment that is now a permanent feature of the “labour market.” According to the ILO, global unemployment now stands at over 200 million and is still rising. This is a colossal waste of humanity’s potential.

Under a socialist planned economy, everybody’s productive talents could be utilised to the full and the burden of necessary work shared between all. Under capitalism, much of the work that could be done by machinery is still done by humans, as it is more profitable to employ low-wage workers than invest in more efficient technology. Under socialism we would unleash the potential of machinery to its full, raising productivity and allowing us to reduce the working week to a few hours.

Compared to a rationally planned economy, capitalism is enormously wasteful. It is estimated that we produce enough food to feed the world’s population several times over. Yet millions of tonnes of food are destroyed every year, in order to keep market prices (and thus profits) high. At the same time, over 5 million people starve to death each year, as they cannot afford to buy food. From the standpoint of society’s needs, vast sums of money are wasted on totally unproductive expenditure each year. In 2016 alone, nearly $500bn was spent globally on advertising and $1.69tn on military expenditure!

The idea of planning production is not alien to the capitalists, so long as profit wins. In fact, within every capitalist company there is a high degree of planning. Take, for example, a car manufacturer such as Ford. They do not leave it to the “market” to decide where and when each component will arrive at the plant, when and how many workers will be at their shifts and where the finished cars will be distributed. These things are planned well in advance on a global scale, using computers, in order to reduce production costs and maximise efficiency.

However, when it comes to planning production as a whole, the capitalists recoil. This is as the only genuine way to plan the economy rationally for all our needs would involve the working class taking over the commanding heights of the economy and placing them under democratic control – i.e. out of the hands of the capitalists.

The fact that planning is more efficient than the market was recognised during WW2, when in Britain a large degree of planning was introduced by the state into the economy in order to produce enough munitions to fight the conflict and to sustain the home front economy with very limited resources.

The rise of the USSR from a backward, semi-feudal country to become, within decades, the world’s second superpower, is testament to the benefits of planning. However, due to the bureaucratic nature of planning under Stalinism, the economy eventually seized up under the weight of corruption and mismanagement.

Marxists do not envisage the implementation of a socialist plan of production in a top down bureaucratic fashion but instead involving the widest layers of society in determining what resources we have, how they can be most effectively used to meet our needs in harmony with the environment.

The fact that 8 billionaires control as much wealth as the poorest half of humanity combined shows the real meaning of capitalist “efficiency.” Under socialism, with workers’ control and management, we would be able to utilise all of our resources – human, material and scientific – and combine them efficiently so as to maximise our well-being and live life to the full.

Why is it that Marxists talk of the World Revolution? Isn’t that going a bit far? Shouldn’t we just focus on getting socialism in Britain instead?

Genuine Marxists have always been internationalists. Marx and Engels famously wrote in the Communist Manifesto “the working men have no country”, and “working men of all countries, unite!”

Genuine Marxists have always been internationalists. Marx and Engels famously wrote in the Communist Manifesto “the working men have no country”, and “working men of all countries, unite!”

To put these ideas into practice, Marxists built up a series of revolutionary international organisations, starting with the International Workingmen’s Association, founded by Marx and Engels, and later the powerful Communist International, founded by Lenin and Trotsky. In these organisations, national “parties” were regarded only as sections of a single world revolutionary organisation.

This was not due to any utopian ideas, or sentimentality. The necessity for a worldwide revolution arises from the development of capitalism itself as a worldwide system.

In the early years of capitalism, the development of nation states were a progressive factor in taking society forward. In contrast to the isolated city-states and principalities found under feudalism – each with their own laws, customs, measures, and taxes – larger states were developed which unified nations into single markets and political systems.

This was necessary for capitalism to take off, since the markets of small cities and regions were insufficient for large-scale industry.

At a certain point however, even the expanded markets developed by nation states proved insufficient to keep up with the growth of the productive forces of one country. The entire world was thus colonised by the imperial powers, resulting in the development of a world market.

The nation state, from being a progressive factor that encouraged growth, turned into its opposite: a regressive fetter on the development of humanity, which requires the fullest and freest use of the resources of the whole world, unconstrained by borders and competition for resources.

Today, no single country can escape the crushing dominance of the world market, which functions as an interconnected whole. Hence the attempts to overcome this through trade blocs such as the EU, and various other treaties. However, as the crisis in Europe demonstrates, even these giant trade agreements are unable to shield their members from the effects of the crisis of capitalism, as one government after another faces unrest and bankruptcy.

So-called free competition under capitalism tends towards monopoly, as the stronger companies swallow up the weak. This tendency has resulted in the emergence of truly global corporations, the budgets of which far surpass those of many nation states.

The flip side of these giant companies is that they present the workers of different countries with a common enemy. “Workers have no country” has never been truer. For example, the miners employed by global commodities giant Glencore in South America, Africa, and Asia have far more in common with each other, than they do with their respective national ruling classes. Workers in all countries share a common class interest in changing society.

The development of the world market and global companies also means that the crisis of capitalism is globalised. The only answer for the ruling class of each country is to “restore profitability” by attacking their workers’ wages, terms and conditions, and public services – i.e. a global “race to the bottom.”

This global austerity is producing a global backlash. Revolutionary developments are taking place in one country after another. Furthermore, a successful socialist revolution in one country would have a powerful effect on all others – all history shows that revolutions rarely stop at national borders.

For socialism to truly set free the potential of humanity, it must be more productive and more efficient than capitalism, which is based on exploiting the resources of the whole world. Rather than these resources being plundered by a handful of super-rich capitalists, they can only be rationally developed for the benefit of all by the working class coming to power in all countries, voluntarily united in a Worldwide Federation of Socialist States. This is why we are internationalists.

Forward to the World Revolution – we have a world to win!

Without the profit motive, wouldn’t innovation just grind to a halt?

We’re often told that socialism is a nice idea in principle but would inevitably fail as, without the drive for profit, all innovation would grind to a halt.

We’re often told that socialism is a nice idea in principle but would inevitably fail as, without the drive for profit, all innovation would grind to a halt.

Whilst it’s true that the past 300 years or so have seen some of the most significant technological breakthroughs in human history, it is incorrect to see personal enrichment as the only driver of innovation.

Our hominid ancestors developed the earliest stone tools approximately 2.6 million years ago. Between then and the earliest believed development of class societies about 8-10,000 years ago, our predecessors discovered how to use fire, construct shelters, weave clothing, create musical instruments, paint walls, spin ropes, fire pottery, and much more.

Throughout human prehistory, all property was held in common by all members of the tribe or clan. There was no money, no rich or poor, no exploited and exploiters. The survival of the group relied on all members pooling their skills and work through cooperation. Labour saving innovations would collectively raise or maintain the living standards of the entire tribe.

This began to change with the development of agricultural techniques and with it the possibility of a small parasitic class living off the surplus labour of others.

It is true that competition between ruling classes, for example between different ancient empires, gave added impetus to develop technology. Generally, those with the most efficient economies, particularly when it came to war, would conquer those who were less developed.

This competitive drive reached its fullest form when the early bourgeoisie threw off feudal domination and paved the way for capitalism.

Competition between capitalists forced them to invest a part of their profits in new labour saving technology. Those that were ahead of the game could produce commodities more cheaply and thereby drive their competitors out of business. As such, the early period of capitalism saw the productivity of labour develop to a far greater extent than previously.

Today however, mainstream economists are left scratching their heads at what they call the “productivity puzzle”: why has global productivity flatlined and even declined since 2008? Does this mean innovation has ground to a halt?

For Marxists, the problem is not a lack of innovation but primarily an inability for capitalists to profitably utilise new labour saving technologies. Why invest in expanding production, when the world market is already saturated as a result of the crisis of overproduction?

And with the lowering of wages and increasing “flexibility” of labour since the crisis, why invest in expensive labour saving machines, when it is cheaper, i.e. more profitable, to employ workers on poverty wages?

Hence, rather than driving innovation forward, production for profit now holds it back. Most workers know very well how they could improve the efficiency of production at their workplace. However, they keep these ideas to themselves, as to implement them would result in unemployment for some and intensified workloads for the rest. It is the bosses and shareholders who would receive the benefits.

Under socialism, everyone would be incentivised to fully utilise the most efficient labour saving technology, as everyone would then benefit from shorter working hours. Rather than creating mass unemployment, as under capitalism, with a planned economy we could harmoniously share out all the necessary work amongst everyone, with no loss of pay.

It is not true that private enrichment is the only factor that encourages people to innovate. In fact, most innovators under capitalism work either in university research labs, or in the Research and Development departments of large companies. Their discoveries rarely make themselves rich; instead the profits go to the shareholders of the companies that fund their work.

Far from grinding to a halt, under socialism innovation and science would truly be set free to allow humanity to reach its full potential. With the lowering of the working week, access to education for all, and democratic control over production, innovation would no longer be the preserve of a privileged layer for the benefit of a few, but would be opened up to all, for the benefit of all.

Are Marxists in favour of violence?

Contrary to the popular view of Marxists as bloodthirsty revolutionaries, the reality is that Marxists are in favour of a peaceful revolution to overthrow capitalism. Only psychopaths would actively favour a violent revolution, should a peaceful path be possible.

Contrary to the popular view of Marxists as bloodthirsty revolutionaries, the reality is that Marxists are in favour of a peaceful revolution to overthrow capitalism. Only psychopaths would actively favour a violent revolution, should a peaceful path be possible.

The problem is that history teaches us that no ruling class has ever given up its power and privileges without a fight. Does that mean the working class should simply just accept being exploited and renounce the struggle for socialism?

No, Marxists are not pacifists. We do not agree that simply because the ruling class – a tiny minority – is prepared to use violent methods to maintain its grip on society, we should give up the fight for a better world.

How then do we minimise the violent resistance of a ruling class who refuses to leave the scene of history? Paradoxically, not by renouncing violent methods but by preparing our class to defend itself by meeting any resistance head on, with force if need be.

Imagine if in a battle, an army of 10,000 unarmed soldiers faced a group of ten enemies, each equipped with a machine gun. A massacre would ensue. But if the 10,000 were all similarly armed, they would likely force the 10 enemies to surrender without even a single shot being fired.

History is full of such examples. For instance, Salvador Allende in Chile imagined that by signing a pact with the army to “respect the constitution”, the capitalist class (armed to the teeth) would peacefully submit to the will of the (unarmed) working class.

The Chilean masses however were not so naive; over one million workers protested in front of the presidential palace in 1973 to demand arms to defend their revolution. With their calls tragically unheeded, General Pinochet launched a military coup only days later, violently imposing a dictatorship in which tens of thousands were brutally rounded up, tortured, and killed, whilst millions more suffered at the hands of the regime.

In contrast, the 1917 October revolution in Petrograd was an almost bloodless affair. This was due to the meticulous preparation of the Bolsheviks in politically winning over the Petrograd garrison and in creating a workers militia to defend the working class from armed counter-revolutionary gangs.

The taking of power was described as more like a police operation, whereby in a highly organised way, groups of soldiers and Red Guards took over the centres of power and brought them under the democratic control of the soviets.

Despite a few small attempts to violently overthrow the Bolshevik government, the former ruling class of Russia became extremely demoralised, because they came up against a movement of millions prepared to sacrifice all in their fight to change society.

It was only with the intervention of outside imperialist forces – terrified of the revolution spreading to their own countries – that the real bloodbath of the civil war began. Supplying the counter-revolution with 21 foreign armies of intervention, as well as finance, arms, and advice, they attempted to drown the revolution in a sea of blood, in defence of their own profits.

We can see then the disgusting hypocrisy of the ruling class when lecturing Marxists against violence – it is precisely against their violence that we will need to defend ourselves!

Such pacifist moralising from the capitalists is particularly disgusting, coming from a class that sent tens of millions of workers to their deaths in two world wars, for the purpose of re-carving up the globe according to their own financial interests.

We must emphasise however, that it is entirely possible for the working class to take power peacefully, provided we are prepared to defend ourselves from any violent backlash of the capitalists. Unlike Russia in 1917, the working class in most countries today is the overwhelming majority of society. The ruling class – in crisis everywhere – will find very few supporters prepared to fight for restoring their obscene privileges.

With the implementation of socialism on a world scale, we will finally do away with this brutal system that sees a tiny minority violently defend its right to exploit and oppress the overwhelming majority of the world.

Is democracy compatible with socialism?

It is often argued that socialism and democracy are somehow “incompatible”, usually by quoting the historic examples of Stalinist Russia and the so-called “socialist” states modelled on its image. However, far from being incompatible, genuine Marxists have always argued that real democracy is essential for socialism to work and flourish.

It is often argued that socialism and democracy are somehow “incompatible”, usually by quoting the historic examples of Stalinist Russia and the so-called “socialist” states modelled on its image. However, far from being incompatible, genuine Marxists have always argued that real democracy is essential for socialism to work and flourish.

Under the “invisible hand” of the market, the laws of capitalism function without any overall control or plan. However under socialism, production must be consciously planned to benefit all. It is not possible for an army of bureaucrats sitting in offices to harmoniously plan production to meet the needs of billions of people across the world. Instead the widest layers of the population must be involved in the task of administering society, in order to realise their full potential.

In order for production to be planned well under socialism, it is vital that the working class has democratic control over the economy. Where this control is absent, it can lead to all sorts of bureaucratic waste and mismanagement, as was evidenced by production within the USSR. For example, in order to meet production targets (and therefore receive their bonuses), bureaucratic managers would often find ways to meet the targets on paper, whilst in practice producing wasteful or defective goods.

One case of this was that of a factory ordered to produce a “million shoes”. The manager ordered one million left-foot shoes to be produced, so satisfying the target on paper! Such examples could be multiplied at will in the Stalinist regimes.

This situation could only prevail because the workers themselves were excluded from having control over production and politics. A regime that demands blind subservience to privileged bureaucrats, leads to demoralisation and apathy amongst the masses. In a climate where all criticism is excluded, the potential innovation and dynamism of the working class is suffocated.

It is only under genuine socialism, with the working class in power, that real democracy for the millions is even possible.

Capitalist “democracy” means that the vast majority of the working classes are excluded from democratic participation in society in a thousand ways. Not least is the fact that millions are forced to spend the bulk of their working life stuck for long hours in a factory or an office, and are often too exhausted to be then involved in political activity.

Instead of having real control over our lives, we are (to paraphrase Marx) offered the opportunity to vote every five or so years for a member, usually of the ruling class, to mis-represent us in parliament. Even then, Parliament remains a screen, hiding where the real decisions affecting us are taken – in the boardrooms of the banks and big businesses.

On the basis of capitalism, it is the ruling class who dictate to parliament, not the other way around, as evidenced recently by the experience of the SYRIZA government in Greece.

Workers’ democracy under socialism, i.e. democracy for the millions, would be far more democratic than anything available under capitalism. Workers in every workplace and neighbourhood could elect delegates to workers councils which, unlike Parliament, would have the authority to actually implement their own decisions. All representatives would be democratically elected; crucially however they must also be held to account and subject to the right of recall.

A socialist planned economy would allow for the rapid reduction in the working week. To discourage careerism, all elected representatives should be paid no more than an average pay of a worker and should not hold office for more than a certain period to permit maximum involvement in running society.

Ultimately it is capitalism that is incompatible with genuine democracy. When workers elect governments that threaten the profits of the ruling class, the most “democratic” capitalists have not hesitated to install military dictatorships, such as in Latin America and the Middle East. Only with workers’ democracy, on the basis of socialism, will politics be transformed from the democracy of the few, to the democracy of the many.

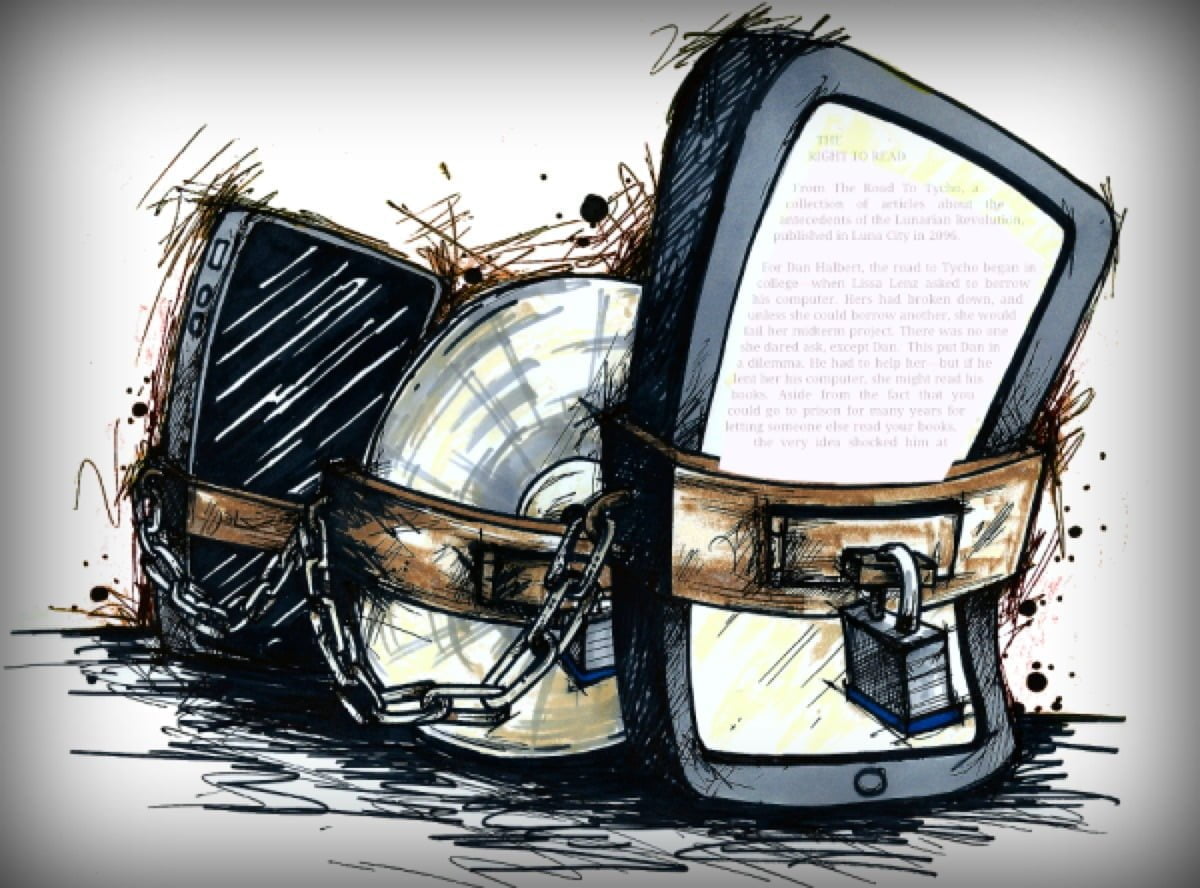

Is it possible to have a revolution when all the mainstream media is against us?

We often hear that although a socialist revolution would be great, it wouldn’t be possible “since all the mainstream media is against us”.

We often hear that although a socialist revolution would be great, it wouldn’t be possible “since all the mainstream media is against us”.

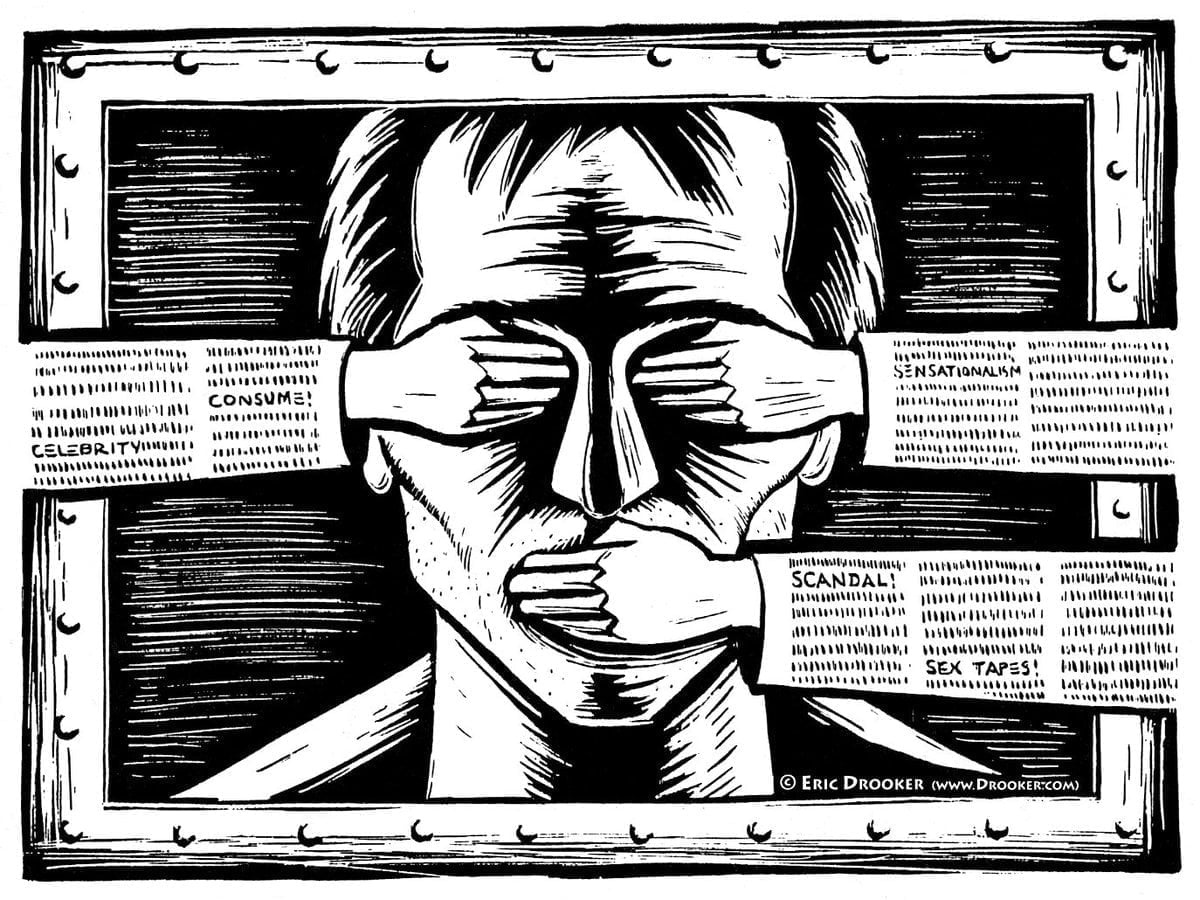

It is true that the media helps to shape public opinion. In fact, along with schools, universities and religion, it is one of the chief tools the ruling class use to impose on us those conceptions of society which they wish the masses to accept.

In Britain, two billionaires – Rupert Murdoch and Lord Rothermere – together control over 50% of all national papers sold. Including online media, just five companies control 80% of the UK market. That’s just Britain! In the USA, six companies, owned by 15 billionaires, dominate the entire media.

With a handful of billionaires owning the vast majority of the world’s media, it is no wonder that the editors and journalists they employ are those that will faithfully toe the line and further their owners’ interests.

This can be seen in Britain, where newspapers accounting for 80% of the share of the national print media supported the Tories in the recent (and indeed most) elections. The historical exception to this was their support for Tony Blair’s “New Labour” governments, since the Blairites clearly stood for the interests of big business.

What about those papers supposedly on the left such as the Guardian and the Mirror? They may well take aim against the Tories but, when it comes to capitalism as a whole, they are reliable defenders of the system. Take, for example, their outrageous reporting of the Bolivarian Revolution in Venezuela, or the non-stop vitriol directed towards Jeremy Corbyn.

The only difference with the BBC is its supposed ‘impartiality”. Of course, in reality it is by no means impartial when it comes to the class struggle. Take the BBC’s treatment of the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike, when footage was edited to give support to the police against the miners. When the BBC was established, the ruling class debated whether to incorporate it fully into the state. In the end, it was decided to give it the veneer of impartiality and independence, so all the better to deceive people when it really matters.

Despite all this concentration of the media in the hands of the ruling class, we should by no means despair as to the prospects of socialism and revolution. The capitalists can say whatever they like in the media but when it no longer corresponds with people’s life experiences, they’re no longer listened to. The ruling class can inform us what a wonderful system capitalism is but when there is mass unemployment, poverty wages and a housing crisis, their propaganda starts to fall on deaf ears.

This can be seen with the media’s treatment of Corbyn. During the June election and before, all the mainstream media joined in a non-stop chorus of abuse against Corbyn, coordinated by the establishment. They threw everything they had against him, from attacking his personal style tastes, to allegations of terrorist sympathies.

Although these attacks had a certain effect on some layers, by and large they failed to achieve their aims. It was clear to many that the billionaire press were attacking him, as the programme he stood for challenged their profits. Rather than dirtying Corbyn’s name, the media dirtied themselves in the eyes of millions, who could clearly see what side of the class struggle they were on.

Such a process reaches its fullest expression during revolutionary periods, when the class struggle reaches its peak. Take, for example, the military coup in Venezuela against Hugo Chavez in 2002, which in large part was organised and backed by the capitalist media. Their control of the airwaves did not prevent millions coming out onto the streets to defend their revolution and defeat the coup.

Similarly during the Russian Revolution in 1917 when, before October, the capitalists sent trainloads of their newspapers (distributed for free) to troops at the front lines. The troops simply burnt these papers by the bundle, yet would rush to get the revolutionary press, which was eagerly read by millions.

We must develop our own press to counter the lies of the likes of Rupert Murdoch and his class. We have confidence though that once the working class moves into action to change society, no amount of capitalist propaganda will hold us back.

Do we need a revolutionary party?

Many agree on the need for a revolution to set humanity free from the horrors of capitalism. However, not everyone agrees on what is necessary for such a revolution to be successful.

Many agree on the need for a revolution to set humanity free from the horrors of capitalism. However, not everyone agrees on what is necessary for such a revolution to be successful.

According to most anarchists, not only is a revolutionary party unnecessary but it is positively harmful. They see capitalism just collapsing following an outburst of revolutionary energy from the masses, or a general strike. A classless and stateless society will then proceed to be spontaneously formed.

Marxists agree that mass revolutionary movements will take place with or without a revolutionary party to lead them. It is the inability of capitalism to take society forward which leads to an accumulation of anger and frustration below the surface. Eventually, even the smallest spark can be sufficient to bring this anger out in a mass movement.

Occupying town squares, or even calling a general strike, is not sufficient however to overthrow capitalism. Such a movement, in effect a struggle with arms folded, means that the ruling class can simply wait it out, until the workers become exhausted.

In order to see the revolution through to success, it is necessary for the working class to take power out of the hands of the capitalists and construct a new form of state. This will not happen “spontaneously” but requires conscious planning, organisation and, leadership.

The working class is not one uniform bloc. Certain layers draw revolutionary conclusions at different speeds. Within it are more advanced, class conscious layers, as well as more backward layers still under the influence of the ruling class.

In every outbreak of class struggle, whether in a strike or a revolution, the more advanced layers in every workplace or movement end up playing a leading role. In this sense they are the “vanguard” of the working class, fighting on the front lines and drawing other layers behind them.

In a revolution, this vanguard can act as a powerful lever in leading the working class to victory, provided it is organised in a party armed with the correct ideas to change society.

After all, a revolutionary party is first and foremost a programme, containing the concrete steps necessary to change the world. It will adopt certain methods or tactics of struggle to realise this programme. The apparatus of the party is only the vehicle to put these ideas into practice.

This programme does not fall from the sky but develops out of the class struggle against capitalism. A revolutionary party, by generalising the collective experience of the labour movement, is able to draw the various demands together (such as ending unemployment, and raising wages) and define the concrete tasks necessary for their realisation, such as taking over the commanding heights of the economy and planning production for need.

Such a party, if it has deep roots in the working class, can act as a catalyst in the development of a revolutionary consciousness amongst the masses. However, its most vital function becomes clear only when the question of power is posed directly, which arises in every revolutionary situation.

If led by resolute leaders who inspire confidence in workers and who are able to clearly define the concrete tasks involved to take the struggle to the next stage, such a party, through organising the vanguard, can draw behind it the vast majority of the class towards the conquest of power.

Such an organisation acts like a piston box around steam. By concentrating all the energy of the masses to the point of attack, it becomes a powerful force for changing society. Without this however, the energy becomes dissipated, like steam in the air.

We only have to look to the experience of the Tunisian or Egyptian revolutions to see this analogy borne out in practice. Millions took to the streets seeking change but, without a party with a clear programme of how to achieve that change, that energy became dissipated, leaving capitalism intact.

Revolutionary movements are being prepared in all countries by the crisis of capitalism. Therefore to ensure their success, it is vital that we work to build an international revolutionary organisation, with sections in all countries, which will be able to play this leading role when the time comes.

Is it possible to have socialism without destroying the planet?

We often hear that socialism sounds great in principle, yet in practice it would destroy the planet. The reasoning being that under socialism, we would need to massively increase industrial production in order to produce enough of everything for people to take things freely. This expansion is assumed to come at such enormous environmental cost that even the future of life on Earth could be at risk.

We often hear that socialism sounds great in principle, yet in practice it would destroy the planet. The reasoning being that under socialism, we would need to massively increase industrial production in order to produce enough of everything for people to take things freely. This expansion is assumed to come at such enormous environmental cost that even the future of life on Earth could be at risk.

It is true that under capitalism,our planet is facing an environmental catastrophe. Consider the pollution of water supplies (widespread in the USA due to fracking), the destruction of rainforests, the toxic fouling of the atmosphere and the pollution of the oceans. This is on top of the rise in greenhouse gas emissions.

Although the ruling class attempts to put the blame for these problems at the foot of individual “consumers”, the reality is that these are inevitable features of a system that only produces for profit.

The costs to the environment do not feature on the capitalists’ accounts. Their only concern is to make money. If they increase their costs, for example by installing filters on their chimneys, they will lose out to other capitalists who are not so environmentally inclined. Competition on the market thus forces the capitalists to produce in the cheapest way possible, without regard for the environment.

But what about regulations? Can’t governments step in to make sure the planet is protected? It is true that governments around the world have passed all sorts of environmental legislation, often as a form of protectionism against imports. Nevertheless, the capitalists find thousands of ways to evade these rules, such as the recent “emissions scandal” at Volkswagen, where special software was installed in cars to allow them to cheat their pollution inspections.

Ultimately, we cannot expect capitalist governments to solve the environmental crisis. Every government is in competition with each other to create the most “business friendly” setup for capitalists, i.e. reduce any kind of obligations that would impact on profitability. Even if global agreements such as the Paris climate accord can be signed on paper, governments can just as soon tear them up again (as Trump has now done) in order to put the interests of their own capitalists first.

So what about socialism? Rather than leaving production to the “invisible hand” of the market, we could consciously plan production so as to be in harmony with the environment.

A recent study found that just 100 companies worldwide were responsible for 71% of all greenhouse gas emissions between 1988 and 2017. If these companies (and others) were run democratically for need and not profit, imagine the impact we could have on limiting climate change.

The technology already exists to power industry cleanly and sustainably. However under capitalism, the trillions already invested in fossil fuels, and the fact that their use is more profitable, limits the uptake of renewables.

It is estimated that by covering an area of the Sahara equivalent to the size of Wales with solar panels, the entire energy needs of Europe could be met. However under capitalism, European governments are not too keen to give control over their power supply to governments in Algeria, Libya, or Egypt. With a worldwide socialist federation, based on the cooperation of the working class worldwide, such barriers would no longer exist.

Economic growth does not necessarily have to come at the cost of the planet. Goods could be designed to last, instead of fail, and production organised so as to eliminate wastage. With the plentiful resources of the Earth, it is entirely possible to build enough homes for everybody to live well, and much much more. We already produce 2 or 3 times enough food to feed everybody, yet millions starve. Thus the problem is political, not technical.

It is true that socialism in itself is not inherently “green”. However it is only by taking control over the key levers of the economy on a world basis, and removing profit from the equation, that humanity would have the possibility of seriously addressing green issues. Unless we do, it is capitalism that in fact threatens to destroy our planet.

Was the 1917 October Revolution a “coup”?

Over 100 years after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, we are still constantly treated to endless propaganda to the effect that it was all simply a coup d’état, carried out by a small band of conspirators.

Over 100 years after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, we are still constantly treated to endless propaganda to the effect that it was all simply a coup d’état, carried out by a small band of conspirators.

The logic of these attacks is to portray Lenin and Trotsky as power hungry maniacs, who ruthlessly imposed their will over an unwilling population. We are led to believe that, had they not done so, a flourishing “democracy” would have developed in Russia, avoiding the horrors of the civil war.

A revolution is not a one-act drama but a process that unfolds over months or years. Far from being the result of efforts by small bands of conspirators, a revolution ultimately breaks out on a mass scale due to the inability of the ruling class to develop the productive forces of society, i.e. to take humanity forward.

This was proven on a world scale in 1914 with the outbreak of the war, but the crisis was particularly acute in Russia. By early 1917, the troops were freezing and exhausted on the front lines, workers were going hungry in the cities and peasants were being squeezed by their landlords.

The crisis reached breaking point in February of that year, when the masses overthrew the the Tsar. Yet the new so-called Provisional Government, headed by capitalists and landlords, was unable to offer “peace, bread, and land” to the masses who brought it to power.

Alongside the Provisional Government, the workers, peasants and troops set up their own “soviets” (i.e. councils) to represent their revolutionary interests.

However in the first stages of the revolution, the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs) dominated the soviets and used their influence to support the provisional government of the ruling class. Hence the regime stumbled from one crisis to another, as it continued the imperialist war and gave no relief to the masses.

With Lenin’s return to Russia in April, he argued that since the Bolsheviks were in a minority, their task was not to seize power themselves, but to “patiently explain” the need to transfer all power to the soviets. On 5 May 1917 he wrote:

“Anybody who says ‘take the power’ should not have to think long to realise that an attempt to do so without as yet having the backing of the majority of the people would be adventurism”.

Over the summer months, the enthusiasm of the masses for change met with continual resistance from the Menshevik and SR leaders, who refused to take power. Thus their support in the soviets collapsed, as wider and wider layers went over to the Bolsheviks.

By October, the Bolsheviks had won a majority in the Petrograd and Moscow soviets, as well as numerous others. With the peasants rising up in the countryside, the time was ripe to prepare for an insurrection.

To superficial observers, the revolution appeared as a “coup”, due to the relatively small number of people involved in the insurrection, i.e. the taking over of key government and strategic institutions.

As Trotsky noted in his History of the Russian Revolution:

“The tranquillity of the October streets, the absence of crowds and battles, gave the enemy a pretext to talk of the conspiracy of an insignificant minority, of the adventure of a handful of Bolsheviks….”

“But in reality the Bolsheviks could reduce the struggle for power at the last moment to a “conspiracy,” not because they were a small minority, but for the opposite reason – because they had behind them in the workers’ districts and the barracks an overwhelming majority, consolidated, organised, disciplined.”

Had the Bolsheviks not enjoyed this mass support, they would not have held onto power for days, let alone years.

Ultimately, most of the preparation for the taking of power had been carried out months in advance – by the patient explanation of the Bolsheviks in winning over a majority of the workers and troops. Support for the Provisional Government had collapsed; almost nobody was prepared to fight to defend it.

Had the Bolsheviks not seized the moment to take the revolution forward, the result would not have been a “flourishing democracy” but a Russian variant of fascism, as the ruling class would have taken the offensive against the revolutionary workers and peasants.

Wouldn’t everyone be lazy if we’re “all paid the same”?

It’s often argued that socialism couldn’t work as, if everyone is “paid the same”, there would be no incentive to “work hard”.

It’s often argued that socialism couldn’t work as, if everyone is “paid the same”, there would be no incentive to “work hard”.

This argument is wrong on many levels. Firstly, it assumes that those who are paid the most under capitalism work the “hardest”. In fact the wealth of the super-rich is not “earned” from their work but through their ownership of the productive forces. This allows them to appropriate the unpaid labour of billions of working class people around the world.

Many of these billionaires do no productive work at all but pay others to manage their companies and finances. An Oxfam study into the wealth of the world’s billionaires, found that one third was inherited, whilst 43% can be linked to corruption.

Whilst these parasites “work hard” on their super yachts, billions are forced to work 50 or 60 hours or more a week, doing backbreaking labour in return for poverty wages.

Such “hard work” is not encouraged by the fact that different layers of the working class receive higher wages. It results from the necessity to accept any job, in order to be able to put food on the table, pay the rent and bills. The alternative is to join the ranks of the unemployed, which for many means hunger and homelessness.

Secondly, the argument that under socialism “we will all be paid the same” is false.

Our ultimate aim is a communist society, where everybody can take freely according to their needs. However Marxists are not utopians, we do not expect that this will be possible overnight upon the working class taking power. It will require a transitional period (usually referred to as “socialism”), during which some of the features of capitalism will be unavoidable.

As Marx noted:

“What we have to deal with here is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but, on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society; which is thus in every respect, economically, morally, and intellectually, still stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges.”

By taking over the commanding heights of the economy and planning production according to need, it will be possible to make a number of rapid improvements to the majority of people’s lives. For instance, it would be feasible to quickly end unemployment, by reducing the working week, with no loss of pay.

In the same way that access to healthcare in Britain is socialised through the NHS, it would also be possible to provide other goods and services such as energy, internet, transport, and food for free. This is since we produce, or could produce more than enough of these things to go around. This would have the same effect as a massive wage increase for the vast bulk of society.

Yet so long as scarcity exists, certain items would still require distribution through money, i.e. wage payment would still be necessary. It is utopian to think that in the early period following a socialist revolution, everybody would accept being paid the same given their different needs, responsibilities and workloads, or allow those who don’t work but could, to take from society’s wealth.

However, unlike under capitalism, where in many companies the ratio between the lowest and highest paid is astronomical (FTSE 100 company bosses “earn” on average 386 times more than the living wage), under socialism we would significantly reduce this disparity. In the early years of the USSR, the ratio between the highest and lowest paid was officially 1:4, and even this was considered high.

With workers’ control, a massive shortening of the working week, along with the abolition of the divide between mental and manual labour, our conceptions of “work” would be transformed. From a tiring burden, necessary to pay the bills whilst making some billionaire richer, it would become a source of enrichment, or “life’s prime want”.

With the development of the productive forces to such a point where we could easily produce enough of everything for people to take freely, the desire to be “paid” more than others would become meaningless, as money itself would become unnecessary. Far from universal laziness, humanity could finally achieve its full potential.

Do Marxists want to ban religion?

Although Marxism is a resolutely atheist philosophy, genuine Marxists have never wanted to “ban religion”. On the contrary – Marxists have always defended people’s right to practise whatever religion they want. This is a basic democratic right.

Although Marxism is a resolutely atheist philosophy, genuine Marxists have never wanted to “ban religion”. On the contrary – Marxists have always defended people’s right to practise whatever religion they want. This is a basic democratic right.

This misconception comes from the attempts by Stalinist bureaucracies to forcibly suppress the practise of religion. Knowing that you cannot ban ideas, such moves were instead part of the bureaucracy’s attempts to clamp down on any democratic freedoms that could have allowed challenges to their rule.

It is true though that Marxists argue that religion should be completely separated from the state – this is also a democratic principle. Religions and religious institutions should not enjoy any special privileges or power, financial or otherwise, or be allowed to run schools and public services, etc.

Marxists stand for the maximum unity of the working class in the struggle against capitalism. Religious divisions – or indeed any divisions, whether of sex, race, nationality, etc. – only serve to divide us. We welcome any honest class fighters into our ranks, regardless of their religious background.

This does not mean however that we make concessions to religious ideas in our movement’s guiding philosophy or programme. We are not trying to push through a few minor reforms to the system, but to completely overthrow it.

We therefore require clear ideas and tactics, which must be based on a scientific study of the class struggle. Any mysticism or superstitions can only harm our task.

We must point out that in any religion there are always two “churches”, whose interests are mutually opposed. There are those at the top of the church, a minority, connected by a thousand threads to the ruling class. Whilst benefitting from the status quo themselves, they utilise religion to preach passivity, so as to dampen the class struggle. If right-wing thugs attack you: “turn the other cheek”. To your boss who exploits you: “show love and forgiveness”.

On the other side is the overwhelming mass of believers, who see in their religion a path to a better world (even if only after death). To them we say: be wary of any religious leader trying to hold you back from the class struggle. Rely only on your own strength – the strength of the organised working class!

Marxism is a scientific philosophy. We have no need for recourse to the supernatural in order to understand the world and change it. However, we have nothing in common with the “New Atheists” such as Richard Dawkins, who think that religious views will simply be overcome through “rational argument” and propaganda.

Marxists instead recognise that religion has a material base within society. It satisfies a powerful social need. When billions of people face an extremely bleak life in this world, with mass poverty, insecurity, and alienation, the promise of a paradise after death is very appealing.

It is for this reason that Marx wrote:

“Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.”

Any real struggle against the mystical ideas of religion must therefore be waged against the conditions that give rise to those ideas in the first place. This means a resolute struggle to overthrow the capitalist system, which is the source of the oppression and suffering faced by billions.

Under capitalism, it appears that supernatural forces control us. Millions are made unemployed, seemingly by the “invisible hand” of the market. Millions more are killed by war, disease, and poverty. With no control over our lives, it is inevitable that many will find a spiritual explanation for these things in the hands of a god.

With democratic control by the working class over the economy, we can put an end to these horrors of class society. When everyone has real control over their own lives, there will no longer be a need to seek recourse in mystical ideas. If we can create a paradise in this world, there will be no need to console ourselves with the promise of a heaven in the afterlife. Religion would not be banned under socialism; it would wither away.