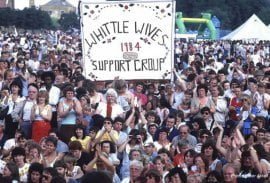

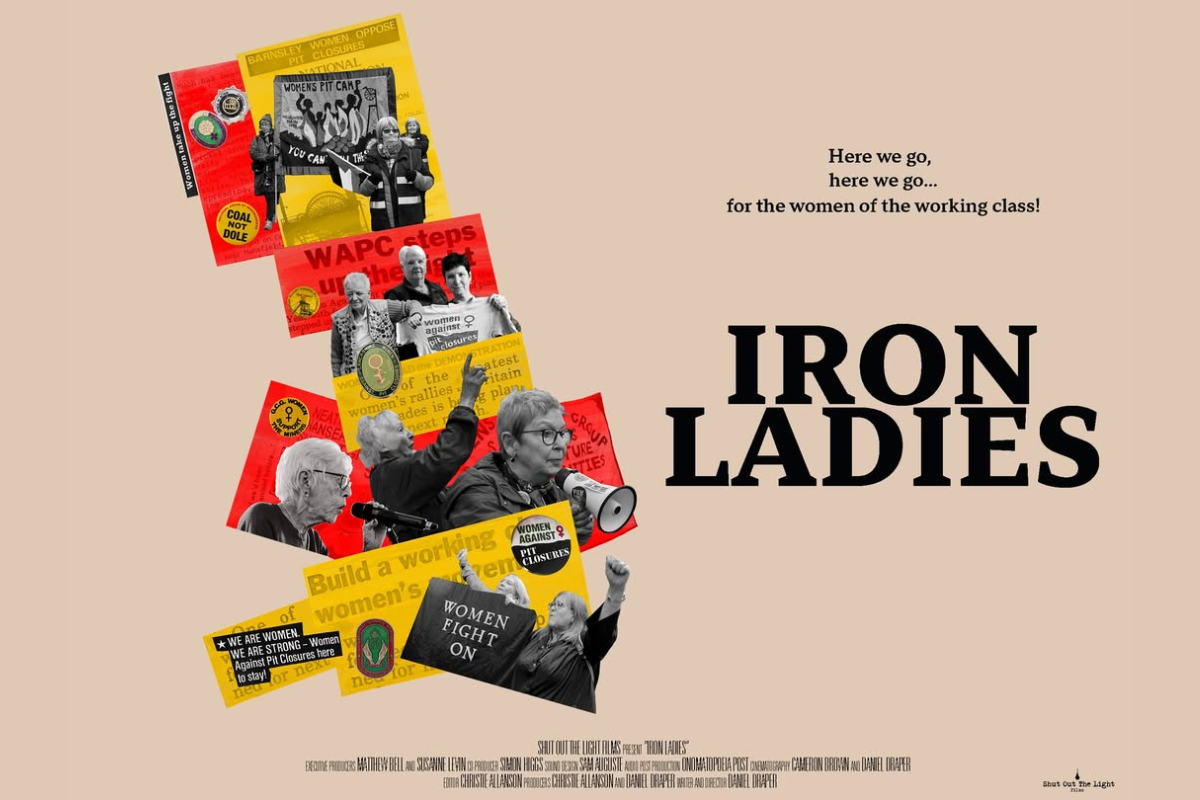

In advance of the Durham Miners’ Gala, taking place this weekend, we publish here two short pieces in which those involved in the Great Miners’ Strike of 1984/85 discuss their memories of the struggle. In the first, Paul Winter recalls the Battle of Orgreave. In the second, Sharon Gaunt and David Martin discuss their experience of growing up in a mining community during the strike.

In advance of the Durham Miners’ Gala, taking place this weekend, we publish here two short pieces in which those involved in the Great Miners’ Strike of 1984/85 discuss their memories of the struggle. In the first, Paul Winter recalls the Battle of Orgreave. In the second, Sharon Gaunt and David Martin discuss their experience of growing up in a mining community during the strike.

Orgreave: just one day

Paul Winter

June 18th 1984 was a most different and bizarre day and it’s taken a lot of years to realise just how significant it was both in terms of political history and my whole life in general. I was arrested a few days before what became known as the Battle of Orgreave as I travelled on the A1 near Blythe in Nottinghamshire.

I spent a day in Mansfield police custody and was put before a specially set up court the same day. The NUM solicitor had instructed me to plead guilty to a charge of obstruction and I was fined £75 (which the union paid). I was told at this point I could now only picket my own place of work and left in no uncertain terms I would be in serious trouble if arrested again.

To ensure the charge stuck a false statement was made of things I said in the car prior to my arrest. In truth I was a young lad just turned 20 and actually sat in the back and said nothing. All the others in the car were older than me. Orgreave was unusual in that we knew where we were going days before instead of the cloak and dagger of the sealed envelope which had been the norm in the weeks prior.

My own Branch suggested I didn’t go due to my earlier arrest so I went with a different Branch which was actually nearer to the estate where I lived.

We arrived very early and unlike before were actually shown where to park then escorted to a large field. At this stage the sheer numbers of police was the major significant difference along with the fact we saw them unloading riot shields which I had never seen before. When the push and shove came I hung well back as I did not want to be recognised by the now long thick wall of police who were banging “Zulu” like on the shields.

The noise was immense and for a few seconds I was stunned by the sheer weight of numbers running back towards me. It was then I realised they were running from horses, what seemed like dozens of horses! As I turned and ran I realised there was no holds barred here. They were wild and manic lashing out at anyone regardless of whether they stood or ran. I saw men dazed and bewildered covered in blood but what struck me was seeing a man in his 50s, hands over his head cowering, and he had pi**ed himself with fear. Not Normandy 1944 but Rotherham 1984!

I got home (not with the same people I went with) shocked and missing a trainer and my tee shirt, which had been tucked in my belt as it was so hot. My Mother’s first words were “What on earth were you playing at!” She had seen the reversed BBC footage with miners throwing stuff first with the baton charge after. I explained what happened many times in the years after but the trick had worked. I kept away from any picket line for months until the strike was broken at my own pit.

I’ve still not been back to Orgreave since and the day seems almost surreal. I actually stroked a horse a few months ago as it pulled a wedding carriage where I work. That might seem odd but I’ve given them a wide berth since 84. They’re actually quite nice when not controlled by a monster!

When our Dad went to jail

John Dunn interviews Sharon Gaunt and David Martin

I have written before about Brian Martin, sadly now deceased, a good friend of mine, socialist, fellow miner and local councillor who was fitted up and framed during the Great Strike after an altercation between strikers and scabs in Chesterfield. Brian was six miles away at the time, helping strikers with their housing benefit. He was jailed shortly after the end of the strike.

In this, the 30th anniversary of that momentous struggle, I spoke to his children, Sharon Gaunt and David Martin about what it was like to be kids growing up during the strike and especially what it was like having their dad jailed for simply fighting for the right to work.

SHARON: I have no bad memories at all of the strike, although the aftermath was difficult. We were never short of friends and the whole community was pulling together. I had started work at a local engineering firm when dad was jailed and everyone in the office was so supportive. The day after he was sentenced they were hugging me and asking if I was alright. I only got one negative comment and that was from the wife of a scab.

DAVID: I was 13 when he was jailed. Seeing him in prison with his head shaved and in prison denim was hard to take. I was bullied at school by scabs kids, they would sometimes follow me singing the Queen song – I want to break free, but I was proud of him.

SHARON: I’m so very proud of dad and everything he stood for and I’m glad I was part of it. If he was here today he’d do the same again. I don’t know if there will ever be anything like it again.

DAVID: Some of my best memories are from during the strike. I would come home from school and go out logging with him in the evenings, then we would take the logs to pensioners who had no other way of heating their homes. We got a food parcel every Tuesday from the strike centre at the Miners Welfare and went for our meals to the soup kitchen in the Social Centre. It’s things like that that have shaped me.

SHARON: I wish he could have seen the disclosures when Thatcher’s cabinet papers proved that everything the NUM said and fought for was true. He would have been so proud, he had passion and taught me never to back down. I’ve not got politically active like David, but I have all those beliefs, all from my dad.

DAVID: Living through those hard times has made me think about others. I now do advice work, trying to help.

SHARON: It was scary at first when he was jailed, we got hate mail from scabs but we soon found out we were never on our own. The phone was ringing all the time from people asking if we were alright and if we needed anything. We would get up some mornings and people had left bags of food outside our door.

DAVID: When the judge sentenced him, he called my dad a coward. He was never a coward. A coward is a scab. Two days after being sent down we got a letter from the National Coal Board. It was his dismissal letter.

SHARON: When dad was eventually released there was a party for him and a fellow striker who was jailed with him, that evening, in the Miners Welfare. He was very tired but insisted on going. The place was full, they gave him a hero’s welcome. He was a hero.

DAVID: For years after, when I was old enough to drink I would go out and blokes would say “Put your money away, you’re Brian Martin’s son” and buy me a drink!

All that has made me who I am. Everything I do I think of dad. He didn’t say much but his actions spoke louder than words.

SHARON: We’ll always be proud, it was an incredible time that I’ll never forget.

DAVID: Yes incredible, such support from food parcels to strikers kids trips out and visits to French trade unionists families. Such memories.

JOHN DUNN: You are right to be proud of your dad, he was an incredible man, a giant. A true unsung hero.