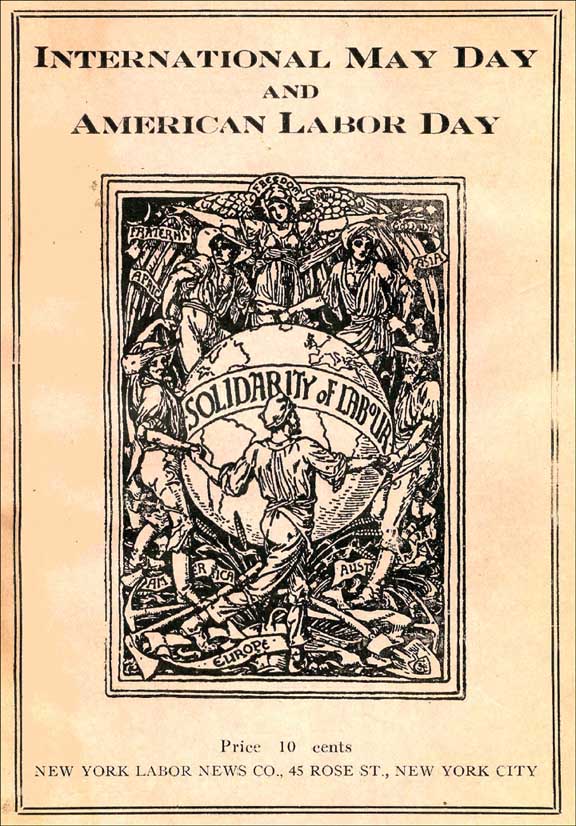

The celebration of May Day as a working class demonstration evolved from the

struggle for the eight-hour day in the 1880s in the USA. The heart of the movement was

in Chicago.

Workers there had been agitating for an 8-hour day for months and, on the eve

of May 1st, 50,000 were already on strike. 30,000 more swelled their ranks the

next day, bringing most of Chicago

manufacturing to a standstill.

On May 3rd police fired into a crowd of strikers at a factory in Haymarket,

killing four and wounding many. A bomb was thrown at the police in retaliation,

killing one officer. Workers were arrested, and four anarchists were hanged.

There was little or no evidence of these men’s involvement with the bomb, and

the rulings of the court became known as a gross miscarriage of justice.

In Paris in

1889 the founding congress of the Second International declared May 1st an

international working class holiday in commemoration of the Haymarket Martyrs

and the red flag became the symbol of the blood of working class martyrs in

their battle for workers’ rights.

Now once again the crisis of capitalism is forcing workers on the world to

move against their oppressors. Once more the tradition of May Day, of

international solidarity, is to the fore.

Last year May Day was celebrated by workers from Finland

to New Zealand, from Athens to Minneapolis.

Both Israeli and Palestinian workers celebrate International Workers’ Day. Where

workers have not won the right to assemble and demonstrate and organise freely,

then May Day is the focus for workers in their struggle for emancipation. In Iran, for

instance, the government banned all independent May Day events across the

country last year. They even prevented workers to hold a picnic in a park

before May Day. For about 1,000 workers and their families, government sent

over 1,000 security forces to shut down the park. This shows what the tradition

of May Day means to workers, and why the bosses fear it.

We have seen the first factory occupations in the UK for nearly thirty years as a

wave of redundancies rocks the British working class.

Where did the idea come

from? It is part of the shared experience of the world’s working class. Des

Heemskerk, leader of the temporary occupation of the Visteon occupation in Basildon and a Socialist Appeal supporter, explains: "The whole question of the occupation

was inspired by the occupation of Waterford Crystal in the South of Ireland.

The idea of occupation spread to Belfast and

from there to Enfield and to Basildon,

where we have had a partial success."

The occupations have beenan inspiration to all workers. The whole idea of occupation came from tactics used by the labour movement in France and also in the USA.

General Motors at Flint, Michigan was occupied in the 1930s. There

were sit-down protests to establish trade unions at Flint. Workers draw inspiration from other

movements.

This could be repeated on a

large scale. The lessons have been carried from Waterford

to Belfast and then to Enfield

and Basildon. The tradition of occupation has

started in Britain

and will be firmly established.

We learn from each others’

experiences, in victories and defeats. Marxism is nothing but the memory of the

working class. As the Communist manifesto points out, ‘The Communists,

therefore, are on the one hand, practically, the most advanced and resolute

section of the working-class parties of every country, that section which

pushes forward all others; on the other hand, theoretically, they have over the

great mass of the proletariat the advantage of clearly understanding the line

of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian

movement’; It is only when Marxism has won control of the labour movement that

the struggles of the working class all over the world will be crowned with the

victory of world socialism.

Workers of the world, unite!