Tomorrow, March 8, is International Working Women’s Day, and to mark this

important event we are publishing this article which has been translated from

the original Italian version. It was first published in issue Number 5 of ‘In

difesa del marxismo’, the theoretical magazine of the Italian Marxist journal

FalceMartello. Although originally written for an Italian audience we believe it

is of interest to labour movement activists and youth around the world.

“The woman free from the man,

Both free from Capital”

Camilla Ravera

in L’Ordine Nuovo, 1921

In 1808, in his Theory of four movements, Fourier explained that

"social progress is measured by the progress of the woman towards

freedom". Later, Marx and Engels analysed the development of human society

in detail, not only from the economic viewpoint but also culturally and in the

relationship between the sexes.

Marxism analysed the origin of women’s oppression and laid the theoretical

basis for overcoming it. In particular Engels, in The Origins of the Family,

Private Property and the State (1884), starting from the scientific and

anthropological knowledge of that time, showed the dynamic nature of social

structures and how these structures are linked to the level of development of

the productive forces.

"The increase of production in all branches – cattle-raising,

agriculture, domestic handicrafts – gave human labour-power the capacity to

produce a larger product than was necessary for its maintenance. (…) As to how

and when the herds passed out of the common possession of the tribe or the gens

into the ownership of individual heads of families, we know nothing at present.

But in the main it must have occurred during this stage. With the herds and the

other new riches, a revolution came over the family. To procure the necessities

of life had always been the business of the man; he produced and owned the means

of doing so. The herds were the new means of producing these necessities; the

taming of the animals in the first instance and their later tending were the

man’s work. To him, therefore, belonged the cattle, and to him the commodities

and the slaves received in exchange for cattle. All the surplus which the

acquisition of the necessities of life now yielded fell to the man; the woman

shared in its enjoyment, but had no part in its ownership. The

"savage" warrior and hunter had been content to take second place in

the house, after the woman; the "gentler" shepherd, in the arrogance

of his wealth, pushed himself forward into the first place and the woman down

into the second. And she could not complain. (…)

"The man now being actually supreme in the house, the last barrier to

his absolute supremacy had fallen. This autocracy was confirmed and perpetuated

by the overthrow of mother-right, the introduction of father-right, and the

gradual transition of the pairing marriage into monogamy. But this tore a breach

in the old gentile order; the single family became a power, and its rise was a

menace to the gens.(1) (Fredrick Engels, Origins of the Family, Private

Property, and the State, Chapter IX: Barbarism and Civilization.)

Since these ancient origins, women have been looked on as inferior beings. A

contemporary of Marx in Italy, the abbot Rosmini, inspired the upbringing of

many “young ladies” from good families and appealed to nature to emphasise

their age-old subjection to men:

"It is for the husband, according to the convenience of nature, to be

lord and master; it is for the woman, and so it should be, to be almost an

appendage, a complement to the husband, entirely consecrated to him and

dominated by his name”(2).

These theories may cause some amusement and sound out of date, but they

formed the basis for family law in Italy right up until 1975, when it was

finally reformed after very hard struggles.

While struggles and debates have arisen around this question in many moments

in history, the rise of capitalism marked a decisive transition which radically

changed the relations between individuals.

Liberation outside the walls of the home

As Engels explains, the oppression of the woman within the household was the

result of change outside it. To the degree in which the labour of the man,

linked to herding and agriculture, began to produce the wealth of those

societies by producing a surplus over and above family needs, which was

"sold", domestic labour ceased to be the fundamental wealth. It was of

a private nature, could not be exchanged for other goods on the market and thus

lost its value. The labour of the man, whose products were exchanged for gain,

became productive, while that of the woman, whose product was not for sale,

became unproductive. This change outside the family marked an overturning of the

balance of forces within it. To quote Engels again:

"We can already see from this that to emancipate woman and make her the

equal of the man is and remains an impossibility so long as the woman is shut

out from social productive labor and restricted to private domestic labor. The

emancipation of woman will only be possible when woman can take part in

production on a large, social scale, and domestic work no longer claims anything

but an insignificant amount of her time. And only now has that become possible

through modern large-scale industry, which does not merely permit of the

employment of female labor over a wide range, but positively demands it, while

it also tends towards ending private domestic labor by changing it more and more

into a public industry."(3) (Fredrick Engels, Origins of the Family,

Private Property, and the State, Chapter IX: Barbarism and Civilization.)

The development of the capitalist mode of production actually had important

repercussions on all women, from those of the upper classes to proletarian

women. It was precisely the processes explained by Engels which pushed bourgeois

women, and even some from the nobility, to demand more rights, and, as we shall

attempt to clarify here by describing some of the struggles at the turn of the

19th-20th centuries, to shake up consciousness and the social system.

The class struggle and the struggle against patriarchal society

However, the capitalist mode of production marked an irreconcilable break

between the interests of the exploited and the exploiters. The capitalist system

pushes the individual to find a role in social production. Thus not only did

bourgeois women come out of their "gilded prisons" to demand a seat in

Parliament or a place in male professions, but also millions of peasant women

and housewives were thrust by want into large-scale production: the factory, the

mill, the mine, the office and the call center have become the place of a

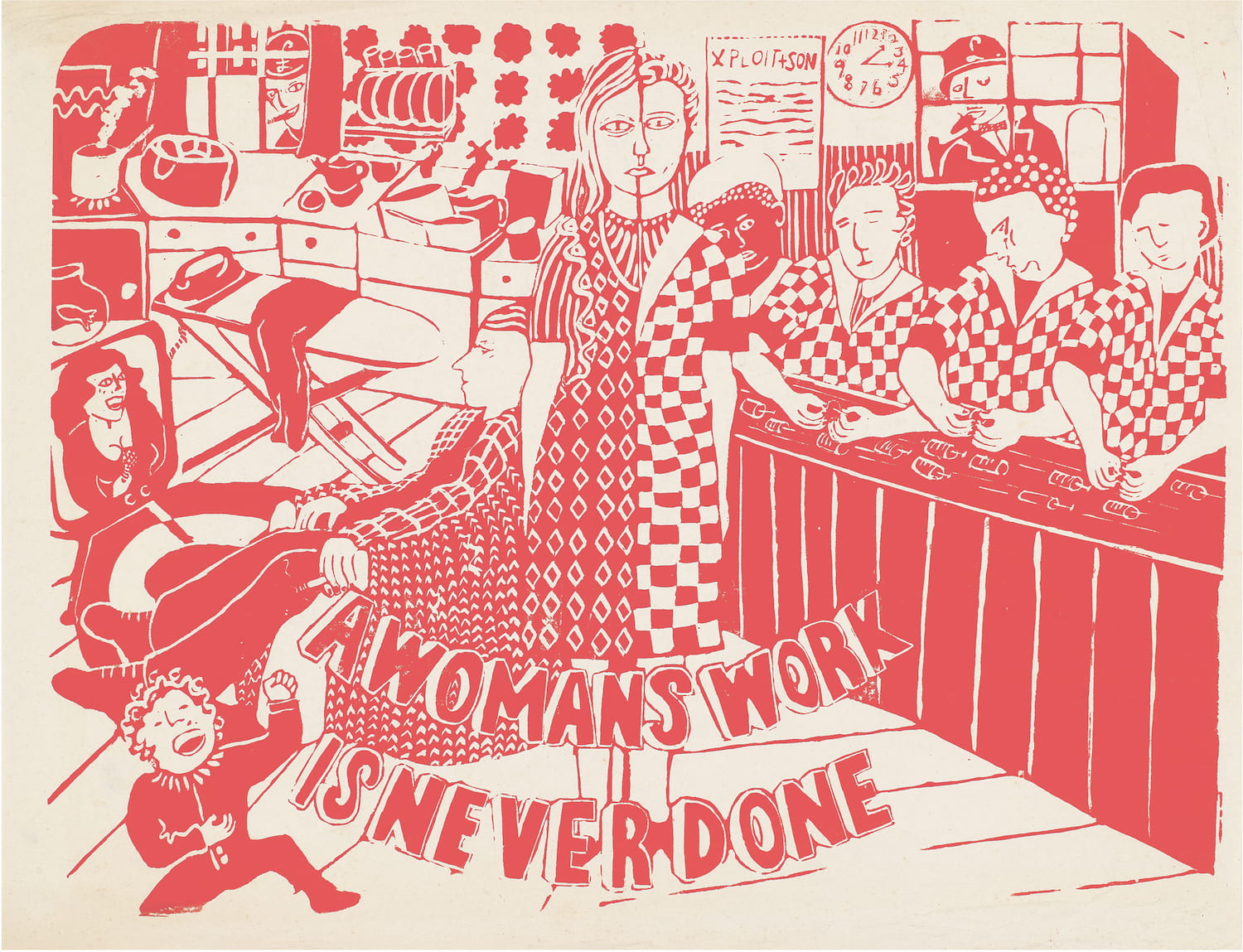

further form of oppression: class oppression. This second burden, however,

brings them out of the solitude of the four walls, gives them the chance to find

other female and male comrades in the fight against their exploited position,

become protagonists in their own lives, break their subjection to men and strike

a blow against patriarchal society. The whole experience of women workers’

struggles teaches just this: the struggle in the workplace is always accompanied

by a crisis in the family, with men looking suspiciously on the new female

protagonism while women, gaining confidence in their abilities, no longer put up

with abuse and ridicule by fathers, husbands and brothers.

Entry into the world of labour, the earning of a wage and, ultimately, the

class conflict, do not automatically lead to the liberation of the woman, but

communists who set themselves this aim must understand the connection between

these two aspects; it is the class conflict that most clearly reveals to women

in general the reactionary nature of the family as a place where individuals,

and especially women and children, suffer oppression. Communists must take

advantage of this objective condition to put forward a different idea of how

human beings can live together, based on the socialisation of economic

resources, of household tasks, of the care and upbringing of children. But above

all they must make it clear that the cause of the tensions and violence that are

part of daily family life lies in the private nature of the responsibilities

that capitalism necessarily unloads onto the shoulders of the family and of

women in particular. So breaking women’s oppression, breaking down this

private character, means making the struggle for women’s liberation part of the

struggle against capitalism. Taking up the women’s question is not just an

extra, but a decisive issue which brings the struggle against capitalism onto

more advanced ground. Communists do not fight this system only because it forces

three quarters of the world into the most inhuman poverty, but also because it

is a brake on the development of culture, science and human resources, and from

a simple brake it is transforming itself more and more into a system leading to

barbarism in human relationships even in the advanced capitalist countries. Thus

the battle is also an ideological one.

The nature of feminism

Up to now we have avoided using the term feminism in relation to the struggle

of the women’s movement and we believe that a few clarifications are needed

concerning this term.

It was Fourier who first spoke of feminism, giving the term a positive value

as it meant the struggle of women against their oppression. However,

historically the term has been taken over basically by movements with a

bourgeois or petty bourgeois leadership, often coming into conflict with the

labour movement and its organisations.

The feminist movement, particularly after the Second World War, produced

ideas and analyses which were unquestionably valid, and in some cases adopted

revolutionary Marxist ideas. However, the fact remains that overall it remained

a prisoner of a reductionist view of the women’s question, which saw it as a

central battle with all women being lumped together regardless of their social

background and separately from all other struggles (wages, social conditions,

etc.).

While it is true that the denial of rights affects women of different social

classes, there is an enormous gap between the conditions of women, according to

the class they belong to, and this distance is inevitably reproduced in the aims

they set themselves.

First of all there is the question of property. Bourgeois women have to look

after their own and their family’s and acquaintances’ property. Proletarian

women, with their class demands, together with their demands as women, are a

constant threat to bourgeois property, which is challenged not only by the

programme of the labour movement (which may be more or less advanced) but

particularly by the methods of struggle (strikes, occupations, etc.) and the

mass character of these struggles.

Secondly there is the problem of the goals of the struggle. Historically the

feminist movement has had many different expressions which we will analyse later

in this text. Here we will try to summarise these objectives: the central theme

for bourgeois women in the feminist movement is the cultural battle. At the

beginning of the 20th century this was expressed in the extension of democratic

rights, such as the right to vote, the right to study and access to the

"male" professions (lawyers, doctors etc.), but it later found its

demands in female protagonism and against a Catholic culture which saw the woman

as the "angel of the hearth" (divorce, abortion rights). This cultural

battle was often accompanied by a strong verbal radicalism and also by

"exemplary" actions aimed at showing the revolutionary and universal

character of those demands. Basically, however, although democratic rights for

women are universal, in other words they involve everyone, posing the cultural

struggle separately from the economic system gives this battle a partial

character. It may have striking effects but does not undermine the system. Hence

the eternal debate as to whether we should demand women’s emancipation or

liberation. The most moderate sections of the movement naturally limited

themselves to demanding a few adjustments to women’s conditions, campaigning for

a more or less slow emancipation process. Other sections, which were more

radical but often more confused, demanded a genuine liberation, but did not

understand that to achieve this they had to go beyond the narrow limits of

feminism and take part in a broad struggle against capitalism, putting forward a

more radical, revolutionary programme within the workers’ movement.

Working women and patriarchal ideology

On the other hand, for women workers, their oppression within the home is

interwoven with social conditions. For women workers this is represented by the

suffocation of housework and child-minding. Unlike bourgeois women they cannot

unload these chores onto wage labour (baby-sitters, maids, etc). Over the last

few decades in the advanced countries there has been a certain involvement of

men in looking after the children and in housework, but the ultimate

responsibility continues to rest on the shoulders of the woman. In the poorer

layers and the working class this responsibility is even greater, as capitalist

society has no interest in socializing it. This situation changes the role of

the woman, and particularly the woman worker, in society; time is dedicated to

the house, the children, running the house in general at the expense of study,

union activity, politics, improvement of working conditions etc. However, while

working class women, unlike bourgeois women, are also oppressed by their

menfolk, they are forced to take a more tortuous and laborious path to free

themselves. The men of their social class do not have a nice, well-paid

profession for them to envy or compete for. Although men workers on average are

better paid than women workers, it is still wage labour. What remains is a

couple and family life which is unsustainable from a human and economic

viewpoint, and inevitably goes into crisis. And here too we see the greatest

difficulties affecting women workers; for them the prospect of divorce means

having to face life as a single person, probably with children (who in 98% of

cases go to the mother), on a starvation wage and with an extra rent to pay.

Capitalism imposes on the women the double burden of work outside and inside the

home. When this burden is unbearable no solution is offered except more

loneliness and a disrupted social life. About half of households in Italy are no

longer of the traditional type (father, mother, child/children); in most cases

they are women desperately looking for a way to emancipation from family

oppression, but while they may escape from their obligations towards a husband,

they cannot escape the women’s role that capitalism in any case thrusts upon

them. The care of the children remains, discrimination in the workplace remains,

economic need remains and even increases, as does the need for human solidarity,

but here the division of roles by sex is once more reproduced.

Women workers, unlike middle class women, can react to this loneliness of

oppression suffered in private by taking up a role in struggles in their

workplace. The class struggle is a collective struggle and demonstrates the

power of women workers, increasing their confidence in their abilities and

helping to make broad layers of the female working class aware of their

oppressed condition as women in society, showing how collective action can

combat the oppression of women too.

In order for this to be expressed in a conscious struggle for their own

liberation, a revolutionary analysis and programme are needed. But the reformist

organizations of the labour movement have gone from a sometimes openly hostile

attitude (consider the Italian socialists who opposed the vote for women) to

posing the problem in an exclusively economic manner (equal pay, conditions,

hours etc.), without taking up the revolutionary implications of the struggle

against women’s oppression and even claiming that the problem was something

concerning exclusively middle class women.

Subsequently, in the absence of an independent class analysis, the reformist

leaders capitulated completely to feminist conceptions, adopting the ideas and

demands of the most moderate sections. To this it should be added that the

feminist movement has always looked on women workers as “second-class sisters”,

partly because they were less open to its arguments and partly because they were

looked on as practically irretrievable victims of male domination of the workers’

organizations. This attitude of self-sufficiency is shown by the almost complete

absence of writings about the struggles of working class women, compared with a

far greater number of publications about the strictly feminist movement, not to

mention the deafening silence surrounding women’s conquests in the Soviet

Union thanks to the October Revolution.

Feminism and the workers’ movement

Having said this, we must seek a correct relationship between feminism and

the labour movement and between the conflict between the sexes and the class

struggle. While the women’s question must be taken up by communists, as

explained above, we must oppose a partial approach which places the cultural

battle at the centre of our campaigns, independently of class origin. This

approach causes a lowering of the consciousness with which women approach their

condition, where women can see only a description of their oppression

without being offered the means to overcome it.

As we have explained, women’s oppression did not originate with capitalism,

but the existence of capitalism represents the decisive obstacle to overcoming

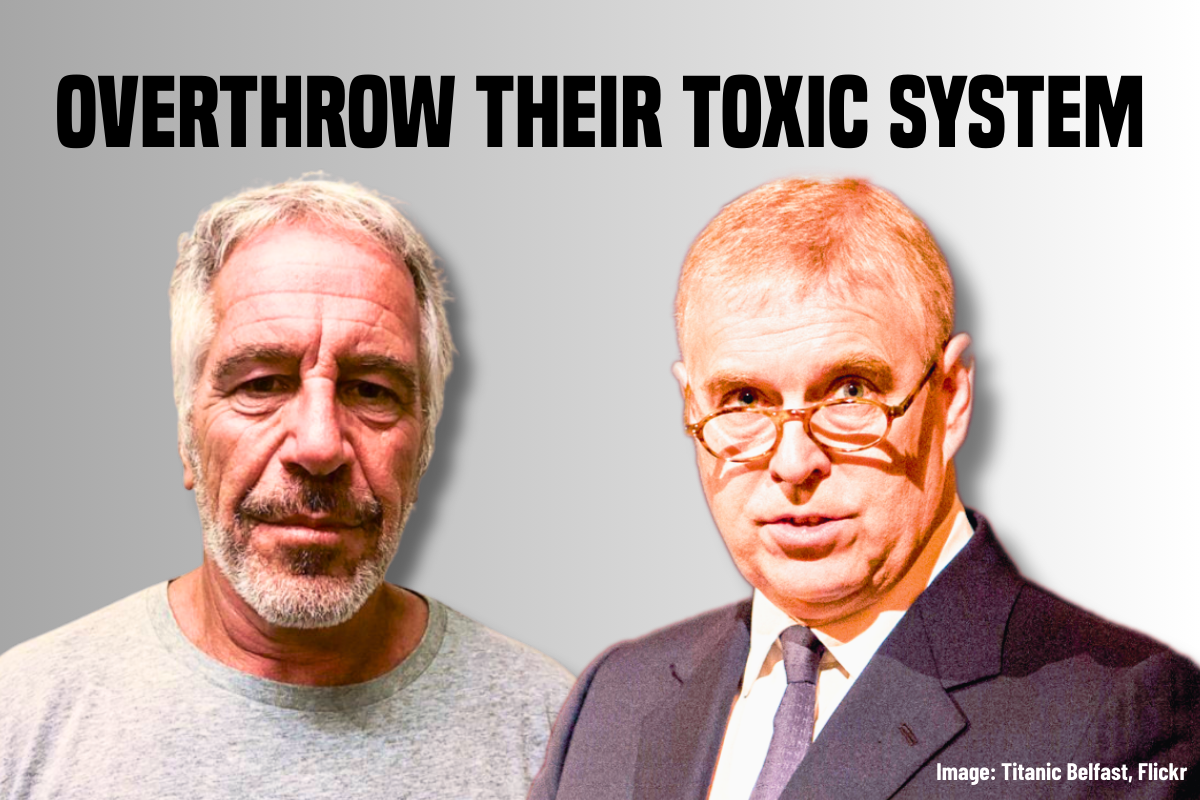

it. This system is obliged to base its rule on the oppression of the working

class and so has to encourage all possible divisions within it. The patriarchal

ideology is fundamental to guarantee a wide layer of female labour where it can

impose inferior wages and conditions, and who can enter and leave the labour

market as needed, acting as a constant downward pressure on the wages and

conditions of the whole working class. In exactly the same way, racism is used

to divide the working class on race lines. Thus, although capitalism thrusts

women into social production, along with immigrants from the more backward areas

of the world, it must at the same time promote the idea that a woman’s duty is

to stay at home to look after her children and family.

Thus capitalism, along with its church ideologues, has become the fundamental

instigator of women’s oppression. For anyone dealing with the women’s

question, it is an inescapable task to expose this link, showing how the

patriarchal culture is used and promoted by capitalism to maintain its rule. Any

struggle that does not take this into account is not only doomed to defeat, but

will be incapable of orienting women workers and those middle class women who do

not just want to adjust their conditions but aspire to genuine liberation.

Finally we must deal with the reasons why the class struggle has a central

place in comparison with the struggle between the sexes. Firstly, from what we

have said so far, it is clear that liberating the woman, or at least creating a

basis for her liberation, means first of all liberating the economic resources

to enable the socialization of housework and child-minding, chores which tie

women to their responsibilities and to their role as women in society. Freeing

these resources means coming into conflict with private ownership of the means

of production, with the ruling class. It means posing the need for a

revolutionary process towards socialism, with the taking of power by the working

class; the nationalisation of the multinationals and of the commanding heights

of the economy with the planning of these resources under the control of the

masses who are exploited today. Only in such a context, in a socialist society,

could they be used for the benefit of the masses themselves.

The central position of the working class in this process is determined by

its role in social production, by the fact that the workers, as a class of wage

labourers, enable capitalism to function and exist, even though they may not be

aware of this power in normal times. Their involvement is therefore decisive so

that their strength can become a conscious force, able to challenge the

established order.

This central position has recently been disputed in the left, by those who

argue that there are other equally important conflicts, such as precisely the

conflict between the sexes, or over the environment. Here we are not questioning

the importance of these issues. What we are stressing is what is the central

contradiction round which all the other contradictions turn.

The women’s question, like the environment, cannot be solved independently

from the abolition of capitalism, a system which is now incapable of

guaranteeing a harmonious development for women and for humankind in general. In

addition it is not possible to conduct a cultural battle without posing the central

question of breaking the motor force of this culture and overthrowing the ruling

class which expresses its interests through that culture.

Thus it falls on the shoulders of the working class, which has the potential,

as explained above, and the responsibility to carry out these tasks which the

capitalist system cannot guarantee, starting now also an ideological campaign,

first of all among women workers themselves and then, once power has been

conquered, implementing our proposals for liberation.

The brief notes which follow are of a mainly historical nature and aim to

illustrate the ideas set out above. As we have already stated, we are interested

in pointing out both the validity and the limitations of the middle class

movements internationally, among the most important of which was the British

suffragettes movement, but for reasons of space we will be concentrating on the

Italian experience.

The bourgeois ‘revolutionary’ women

As early as the 1700s, in both America and Europe, discussion circles on

equality of the sexes grew up, but they were of an extremely moderate nature,

with education as the central issue. Even in Italy, noblewomen debated as to the

usefulness of study and its superiority to fine clothes.

The French revolution was the first time that these restricted circles were

flooded out by the masses, by the common people, who saw the revolutionary

process as their chance to put an end to their poverty and bring about equality

between the sexes. Olympia de Gouges, a bourgeois Ironist, took up these

aspirations and in 1791 presented her Declaration of the rights of women and

of women citizens. Here, however, we see clearly what Marxism later analyzed,

i.e. the superiority of class interests over gender interests. When the

revolutionary process entered a critical stage, with reaction organizing to

strangle the revolution, de Gouges did not understand that, in order to defend

the rights she claimed to be fighting for, it was necessary to defeat the

supporters of the monarchy, otherwise the masses in revolt would be betrayed and

defeated. In 1793 she opposed the execution of the king and Robspierre’s

policy of terror and for this reason was herself guillotined.

However, the struggles which took on a mass character were to come later and

had a clear political content: the right to vote.

A women’s movement developed in the USA, starting with the war between

North and South for the abolition of slavery. The women were not allowed to sign

the abolitionist declaration of the Northern states and for this reason they

founded a women’s antislavery society in 1830. This society began a campaign

which drew a parallel between black people’s and women’s conditions and

began a long series of public debates (which were practically forbidden to women

at that time) with publications demanding the right to vote, the right to

dispose of property and earnings, custody of children in case of divorce and a

better education for women. In 1850, when the first national conference for

women’s rights was held, out of a million workers about a quarter were women.

Although this meant there was a significant proportion of women among the

proletariat, the interest of the women’s associations was focused, apart from

the question of the vote, on the protection of their rights in a bourgeois class

context.

The British suffragettes

The movement which most aroused consciousness through its radical methods of

struggle was that of the British suffragettes, who demanded universal suffrage.

The Labour Party, right from its birth in 1900, had demanded the right to vote

for women. Women activists in the trade unions and the Independent Labour Party

campaigned for women workers to have the vote. In 1903 the Women’s Political

and Social Movement was founded by Emmeline Pankhurst. This association declared

the methods of rallies and petitions to be out of date and began a campaign of

boycotting liberal candidates and of symbolic actions. The suffragettes

disrupted liberal rallies, chained themselves to lamp-posts and intervened at

all political events with placards demanding the right to vote. The government

adopted the methods of harsh repression. There were mass arrests and many women

were condemned to hard labour. In prison they staged hunger, thirst and sleep

strikes; and to prevent them from dying the government ordered force-feeding.

The Labour Party, which supported the movement, denounced the torture in prison,

but the government did not change strategy. In November 1909 two suffragettes

were killed by the police in a demonstration. This led to an increasing spiral

of violence and feminists reacted by setting fire to buildings and railway

carriages, and shop windows and letter boxes were destroyed. The prisons were

filled with women who promptly began hunger strikes. The police, to avoid

torturing them, would release them to rearrest them shortly afterwards,

beginning the famous “cat and mouse” strategy. In 1913 the police raided the

feminists’ premises, suppressed their paper and dissolved their organization.

The same year, in a fit of despair over the blind alley the movement had

entered, a suffragette, Emily Davidson, threw herself in front of the horses

during a race attended by the king and queen, and was trampled to death.

The First World War broke out soon afterwards and many leaders of the

feminist movement embraced patriotic propaganda. Emmeline Pankhurst was released

from prison and the government put her in charge of organizing women to replace

men at work who had been called up.

The suffragette movement was made up of mainly young women from the

middle-class, rebelling against the hypocrisy of society, which required them to

be just good wives at the service of their good husbands. Undoubtedly, however,

they earned sympathy and support among the working class for their

self-sacrifice and perseverance, particularly in the first years. Subsequently,

as the strategy of outrageous actions began to run out of steam, a split opened

up in the movement. One section, led by Emmeline Pankhurst’s daughter Sylvia,

entered into contact with the women of the labour movement in the East End of

London and understood that, in order to really defend women, the vote was just a

means for extending the more general struggle against the oppression of women

and against capitalism. Sylvia was one of the founders of the British Communist

Party.

The struggle of women workers in Italy

The vigour of the movement in Britain was not reflected equally in all the

other countries. In particular the Italian bourgeoisie was too weak and backward

to be able to be influenced by feminist propaganda. As late as 1908 the first

national conference on the women’s question saw the participation of all the

political parties, in the presence of the queen, and was inspired by so-called

“interclassism”. The introduction reads as follows: “Our feminism does not

call to struggle, but on the contrary works for the union of the classes, which

is one of is dearest aspirations”. The inspiration of the participants was so

feeble that they “forgot” to include the issue of the vote for women in the

agenda.

In fact, in Italy the women’s question was not first raised by bourgeois

circles, but by the workers’ movement, which showed the vitality of a new

social class seeking a way out of its own poverty and that of the entire

society.

At the end of the 19th century there were a million and a half women textile

workers, as well as 300,000 peasant women in cottage industries, spinning linen

and hemp. In the textile industry men accounted for only 10% of the workforce.

Other industries with a high percentage of women workers were tobacco and match

production. The first forms of organization of women workers arose in the

textile industry. In 1889 the “Society of sisters of labour” was founded,

which led a large number of strikes to improve wages and reduce the working day

to ten hours. At the trades councils the first women’s sections were formed.

The first, in Milan, was founded in 1890-91 by three socialists: Linda Malnati,

Giuditta Brambilla and Carlotta Clerici. They had to work in very difficult

conditions; poverty and widespread illiteracy were aggravated by the enormous

possibility of blackmail by the bosses and the scorn women were subjected to by

their own menfolk, as witnessed by some letters published by the socialist daily

Avanti. Here are some extracts from one of them:

“Starting with our brothers, who are mainly members (of the union – Ed),

they would not tolerate our showing such a wish, so you can imagine what it’s

like with our parents and, why not, even with our sons. It’s no good, we women

are not supposed to think about certain things, if we do not intend to give up

the joys of the family. Better to be slaves, as we are called, of propriety,

than slaves of ridicule. There is little to be gained and much to be lost.”(4)

However, the dramatic conditions in which women worked forced some of these

“slaves of propriety” to take up militant struggles and join the labour

organizations. From 1880 to 1890 in Italy a wave of struggles gave rise to the

first workers’ associations and organizations: leagues, friendly societies,

unions, trades councils, with the founding of the Socialist Party in 1892. The

movement was very active particularly in the countryside with a high female

participation. The first strike of the women rice-workers took place at

Molinella in 1883, with the demand for a small wage increase. Three years later

came the turn of the rice-weeders at Medicina, with similar demands. At

Monselice the strike was bloodily repressed, with three women killed and 11

others seriously wounded. In the lower Po valley the mobilizations forced the

bosses of the rice fields to resort to organized scabbing. Other women were

brought in from Ferrara and Romagna to replace the strikers, but the struggle

was so militant that also the scab labourers joined the strike and the boss was

forced to retreat. Following this struggle, 42 women workers were tried on the

charges of “attacking the freedom to work and resistance and outrage against

public officials”.

The outstanding courage of these women, who in collective struggle had

succeeded in gaining confidence in their ability and their real power, could not

fail to make itself felt within the household. The ridicule for taking an

interest in union questions and “men’s things” had to give way to respect

and an emancipation in the way of thinking of their equally exploited fathers,

husbands and brothers. The most important sign of this change is to be seen in

the setting up of women’s labour organizations, although skepticism among men

workers remained and many of their organizations were closed to women.

And here we see how the oppression of the woman worker by the men of the same

class is of a different nature from oppression within the bourgeois class. Abbot

Rosmini’s and the ruling class’s prejudices against women were due to the

will to perpetuate bourgeois rule over women and the working class; the

prejudices of men workers and peasants, which are often expressed very brutally,

are based on the ignorance in which the ruling class must intentionally keep

those it dominates. The prejudices of the bourgeois cannot be overcome because

they are the cultural condition of their rule, while the prejudices of the

exploited, though deeply rooted, come into contradiction with their need for

social emancipation and can be overcome by collective action. The working class

has a common interest in freeing itself from the yoke of capitalism: in the

class struggle it comes to understand its strength and to overcome the cultural

poverty in which the bourgeois wants to bind it.

The role of the Socialist Party

So the class struggle is central. The new-born Socialist Party (PSI), whose

principal woman leader was Anna Kuliscioff, focused its attention precisely on

this question. In Kuliscioff’s appeal for the 1897 elections, we read:

“This is the first time that we women too have felt the need to rouse

ourselves. The days are gone when women attended only to the family and lived

outside the struggles which shake modern society. The machine, large industry,

the big store, the general transformation of the social economy, have torn us

away from the family hearth and thrown us into the whirlwind of capitalist

production. In this way the centre of gravity of our interests is necessarily

shifted from family life to social life. (…)

But what is worse is that the woman is exploited and martyred far more than

the so-called stronger sex. The boss looks after his interests, trying to make

us work as much as possible while paying us as little as possible, and as he

meets with no resistance he thinks up a new trick every day. (…)

The latest strikes by the spinners and weavers at Bergamo and Cremona have

laid bare all the shame of our bourgeois civilization. Near Bergamo, where

11,000 out of 17,000 spinners and weavers are women or girls, the working day in

some factories lasts from 4 in the morning to 8 in the evening and the women

workers are paid on average 43 cents (of a lira – Trans.) a day, if they are not

married. The married women get only 40 cents because the boss wants to guarantee

himself against delays due to stoppages caused by pregnancy, childbirth and

illness. And I have not mentioned our comrades who are left in the fields, the

rice women, whose blood is sucked, as well as by overwork, by the leeches that

cling to their flesh, and is infected by malaria, which throws them yellow and

swollen into the dens that serve as sleeping places. No, for the women workers

this is not life any more, but a slow martyrdom!”(5)

This impassioned appeal was part of the central battle of the party, for a

law protecting female and child labour. Such a law was passed in 1902, as a

result of hard class struggles, though in a considerably diluted form compared

with the socialist proposal. However, the Socialst Party was involved in a

heated debate over the women’s question. So long as it limited itself to

demanding greater protection for those jobs which were clearly inhuman,

everybody was in agreement, but when it came to making a deeper analysis large

cracks opened up. The first battle was against economism, i.e. the tendency of

the majority of socialist leaders, including Kuliscioff, to argue that once

women had secured economic emancipation, thereby eliminating their economic

dependence on men, the problem of their oppression would be solved.

Anna Maria Mozzoni in particular, a bourgeois woman from Milan, who had begun

her activity precisely against the bourgeois hypocrisy that denied any autonomy

to women, attempted a more elaborate approach, calling for a battle also on the

cultural plane. Although Mozzoni had joined the PSI right from it foundation

because she saw the liberation of the working class as the central question, she

never succeeded in posing the women’s question in a revolutionary light and,

while she rightly attacked economism, she did not transform her correct

intuitions into a political proposal. So overall the Socialist Party was unable

to pass from a correct propaganda to a revolutionary political programme and

often delegated its concrete interventions to the workers’ leagues and the

unions, which had an even more moderate programme.

As for the issue of the right to vote for women, the failure to understand

the question comes out even more clearly. Although there was never a formal

position against women’s suffrage, interest was to say the least luke-warm, so

that in 1910, at the height of the campaign for women’s suffrage, with

Giolitti (bourgeois politician – Trans.) declaring that giving political rights

to so many millions of women would be a leap in the dark, Filippo Turati, the

party leader, maintained that the “still sluggish political consciousness”

of the mass of women would not bring great benefits and would in fact strengthen

the conservative parties. Although there may have been some truth in this

observation at the time, it was certainly no stimulus to a campaign to awaken

that “sluggish consciousness”. Thus the PSI’s vote in parliament in favour

of women’s suffrage was more of a correct but abstract petition of principle

than a real commitment to carrying through this struggle.

The October Revolution and the Communist Party

A decisive contribution to clarifying the situation and bringing more

advanced positions to the fore came from the international debate in the labour

movement. Clara Zetkin’s articles on the women’s question began to circulate

in Italy too and the breaking out of the First World War precipitated the

contradictions in the PSI. Propaganda in defence of the workers gave way to a

total capitulation to the one’s own national bourgeoisie. Nearly all the

parties of the Second International voted in favour of war credits, opening the

way to the massacre of those same millions of workers it claimed to champion. In

1914 Lenin stood out against this patriotic orgy, denouncing the cowardice of

the Socialist parties and called for the launching of a new international which

set itself the goal of socialist revolution – its supporters were to break with

those Socialist leaders who had betrayed the proletarian cause. The October 1917

revolution gave momentum to the new international and to the advancement of the

debate in the socialist parties, which were forced to take up a position on this

world-shaking event. In 1920-21, splits in the Socialist parties led to the

formation of the Communist parties and the Third International, which proposed

to conquer world power, thus spreading the Soviet system throughout the world

and in particular in Europe, which was in revolutionary ferment.

We cannot here go into those great events and into the effects they had on

the situation in Italy. However, it must be stressed that they had an enormous

effect on the debate on the women’s question in Italy. For the first time the

Communist perspective of women’s liberation gained sufficient momentum to form

a leadership able to carry forward this battle.

In the PSI an opposition crystallised, which was to form the Communist party.

In particular the men and women around the paper Ordine Nuovo in Turin

consciously set themslves the aim of applying the Soviet experience to the

situation in Italy and found themselves in the leadership of the occupation of

the factories in Turin, and of a revolutionary movement on a national scale in

1919-20, known as the biennio rosso (two red years). [See The Occupation

of th Factories 1920 – The Lost Revolution]

This was the climate that tempered the women communist leaders who wrote the

finest and richest pages of the labour movement on the question of the

liberation of women. The leading woman of Ordine Nuovo was Camilla

Ravera, and the slogan which summed up the programme of the group was: “The

woman freed from the man, both freed from capital”. They intervened in workers’

struggles, no longer with the paternalistic attitude of helping the poor and

exploited, but campaigning to bring workers into the leadership of the

struggles, training worker activists and winning workers over to the cause of

communism. It was with this perspective that the intervention among the workers

developed and Gramsci, editor of Ordine Nuovo, made Camilla Ravera

responsible for editing a weekly column dedicated to the women’s question, the

Tribuna delle donne (Women’s tribune).

This space carried articles by Zetkin, Kollontai, Rosa Luxemburg and the main

Soviet leaders, with reports on the situation in the Soviet Union and on the

development of the struggle for women’s liberation in the course of the

revolution. As well as all this there was agitational material for work among

women workers, which had a solid theoretical basis, so that in every article

women’s oppression was highlighted and seen in the right perspective.

Ravera insisted on all the aspects, even the most private side of everyday

life, where the bourgeois ideology was rooted in the working class and even “among

the comrades themselves”. She denounced the squalor of life for the housewife,

the inhuman fatigue to which the women workers were subjected in the home and

the factory, and the brutal physical and moral poverty of most families,

alongside which “all the bourgeois phraseology about freedom, love, the

family, the relationship between parents and offspring, becomes all the more

sickening”.

Their theoretical clarity enabled the women comrades of Ordine Nuovo

to take up an advanced position on maternity too. They denounced the hypocrisy

about the joys of motherhood and declared that for women workers child-bearing

was a misfortune. So long as society did not recognise the social value of

child-bearing and did not take responsibility for its tasks, women should have

the right to accept or refuse it. Thus the right to abortion was put forward for

the first time. Following the Stalinist degeneration this courageous position

was no longer taken up by the Communist Party in the postwar period and it was

not taken up again until the development of the feminist movement at the end of

the 1960s.

In Tribuna delle donne, the emphasis was placed on the emancipation of

women as a lever for the emancipation of men. When demobilised soldiers

campaigned against women’s employment, Ravera did not miss the opportunity to

intervene and denounce patriarchal culture, which saw the man as the

unquestioned head of the family, and the commercialization of marriage and the

relationship of the couple, which forced individuals into a brutal economic

relationship for mutual support.

And she denounced the slavery of capital in the poverty of private life:

“As a slave of capital, the man, corrupted by his own slavery, tries to

gain revenge by subjugating the woman, exploiting her and tormenting her.

Extenuated by work with no joy or purpose, the man seeks oblivion in alcohol, in

drunkenness; the woman, guardian of the hearth, is always the victim of this. It

is the woman who prepares the cannon fodder, the flesh to be exploited, the

flesh for pleasure. The woman will not become free until the man is free”.(7)

The Communist Party, of Gramsci and Bordiga, which was formed from the split

at the Livorno (Leghorn) conference of the PSI in 1921, was preparing on this

basis to develop work among women, while at the same time remaining fully aware

of the difficulties involved in this kind of work. The young Communist party had

1200 branches nationally and 96 women’s commissions, responsible for work

among women workers. Female membership totalled 400 and from 1922 they had a

paper, La Compagna, which sold 15,000 copies.(8)

Defeat and fascism

Fascism suffocated this whole experience at birth. By 1921 the Fascist Party

had grown from just over 300 branches to more than 1000. Attacks by fascist

bands in the first four months of 1921 left 102 dead. In six months 59 workers’

clubs, 119 trades council premises and 141 Communist and Socialist branches were

burnt or ravaged. The organizations of the labour movement were reduced to a

shadow and then forced underground, while working class living conditions

worsened from day to day.

By 1927 women’s wages were half of men’s wages, which had already been

seriously reduced. In an engineering factory producing precision machinery, male

wages ranged from a maximum of 4 lira a day to a minimum of 2.50, while women

were paid 1.50. In the countryside, male labourers earned 9 lira a day, while

women did not get more than 5 lira.

A campaign was launched by the regime about the fertility of women, whose

role was to stay at home and have children. In 1927 women were banned from

teaching in certain university faculties and in high schools, and this was then

extended to some subjects in technical schools and junior high schools; finally

fees were doubled for female students. Fascism inherited the preceding legal

code from 1865, where the man was considered to be the undisputed head of the

family, taking all decisions regarding his wife and children and imposing his

wishes even after separation and death through his will. The woman, as an

eternal minor, had to swear absolute fidelity, adultery being punished by two

years’ imprisonment, while of course the man was free to betray her as he

wished. To this reactionary legislation fascism added a further law, article 587

regarding crimes of honour, whereby any man who killed his wife, daughter or

sister “to defend the honour of the family” had a right to a one-third

reduction of the sentence. This law, together with the law considering rape as a

crime only against morality and not against the person, was not abolished until

the 1980s.

Between 1921 and 1926 the percentage of women working outside the home fell

from 32,5% to 24%, although in some industries low wages and the absence of

qualifications were an incentive to employ women, whatever fascist ideology

might think. From 1936 there was actually an increase in the number of women

workers employed, which, according to the census taken that year, brought the

number of women workers to 5,247,000. In the Second World War female employment

grew further as women replaced men sent to the front; also their role grew in

society and subsequently in the struggle against fascism.

The war years were extremely hard, with hunger and poverty putting the

Italian working class to the test and undermining social stability. In Turin,

workers were doing 10-11 hours a day. 40,000 out of 150,000 workers were women,

air-raids had destroyed or damaged 25,000 homes and tens of thousands of workers

were evacuated to the countryside. There was a similar situation in all towns.

Food and firewood were rationed. Black market prices soared; in 1943 butter rose

from 27 to 160 lira per kg, rice from 2.50 to 25 lira and flour from 1.80 to 12

lira. With rationing coupons a worker in Biella in January 1943 could obtain

1000 calories of food and, as most of the food was kept for the children, it is

clear that the masses were starving. Even the bosses called for an increase in

the food distributed by coupon, because production was falling with working men

and women always sick. A Turin woman worker tells us:

“I was always hungry, also because we always left the little that there

was to the children. But I always came to work, even when I felt ill. Because of

my weakness I had irregular periods; I would miss them one month and then maybe

they would come every two weeks. I was lucky because I never had pains, but one

woman at work couldn’t stand up when she had her periods. Go on, stay at home

on those days, we said. But she was terrified of losing her job. She was alone,

with a child and no husband”.(9)

Meanwhile, as news began to come though of military defeats at the front, the

weakness of the regime was more and more apparent. Women workers with husbands

in Russia were considered as widows. No one doubted reports that Italian soldiers

did not have sufficient protection from the Russian winter and that during the

retreat the Germans had requisitioned the trucks, leaving the Italians to

retreat on foot. Those who did not make it remained behind and froze to death.

In January 1943 a letter from a woman worker was published in a fascist trade

union newspaper: “I do the same heavy job as the male worker I replaced. But

he earned 40 lira a day, while I get only 23 lira. Can you explain the reason?”

The paper gave no trace of a reply.

10 October 2002.

See Part two.