More than a century after the formation of the Labour Party, the

party still remains rooted in the organised working class. Despite

everything, the results of the recent general election confirm the

ingrained support for Labour throughout the working class areas of

Britain.

“The Labour Party gives one third of the votes in its electoral

college to members of its affiliated organisations. The most important

of these brother institutions are the trade unions. A century later, the

party born out of the Labour Organising [Representation] Committee is

still structured as the political arm of the labour movement… The

unions’ power is now a problem.” (Editorial, Financial Times,

14/6/10)

Photo by skuds.Today,

however, the party is dominated by the careerists of New Labour, the

attorneys of capitalism within the workers’ movement. The Blairites are

the new breed of bourgeois infiltrators, creatures of the boom years.

The domination of this trend has resulted in the disillusionment of

millions of Labour’s working class supporters. They were responsible for

the defeat of the Labour government. While many prominent Blairites

jumped ship with golden handshakes and promises of lucrative jobs with

big business, a significant number remained behind to ensure that the

Labour Party is kept in “safe” hands.

For those who want to change society, especially young people, the

thought of joining the Labour Party in the past period has been

distinctly unappealing, to say the least. Workers and youth were

completely repelled and alienated by New Labour’s pro-capitalist

policies, the support for imperialist wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the

corruption scandals, the introduction of tuition fees, and the general

feeling of disappointment. One glance at the Blairite leadership was

enough to place a massive question mark over the party as a vehicle for

socialist change. The leadership, in the phrase of Lord Mandelson, were

completely relaxed about people becoming filthy rich. How could such a

party, so dominated by the right-wing carpet-baggers, ever serve to

change society?

This view is held by many sincere people on the left. However, for

the strategists of capital in the ‘Financial Times’, this is

not at all sure. The right wing control over the party was due to

certain objective conditions. These conditions, mainly an emptying out

of the workers’ organisations and an ebb in the class struggle, were

largely determined by a prolonged boom, which has now come to an end. We

have entered a period of capitalist crisis and austerity, carried

through by a Tory-Lib Dem coalition government. Labour finds itself in

opposition at a time when increasing struggle and social turmoil will be

on the order of the day.

Despite the understandable repulsion towards the right-wing leaders,

it would be a grave mistake to write off the workers’ organisations

because of them. This would be like throwing out the baby with the

bathwater.

Marxism takes the long view of history. We are not mesmerised by this

or that aspect, but seek to uncover the underlying contradictions in

the situation which will sooner or later break to the surface. This is

the whole essence of dialectics, which sees things not as static

entities, but as contradictory processes. The whole history of the

labour movement reflects the ebb and flow of the class struggle. In the

past period, we have been affected by a prolonged ebb. The period we are

entering will be fundamentally different.

Formation of Labour

Ever since the formation of the Labour Party in 1900, there has been

controversy on the left over whether or not to participate in the party.

To develop a correct understanding of this question, it is important to

look at the experience of the past. Our task is to learn from history

in order to avoid unnecessary mistakes. History, after all, is littered

with the wreckage of small sectarian groups who attempted to mould the

workers’ movement into its preconceived plans and failed.

To have a correct approach we need to understand the contribution of

the great Marxists. Both Marx and Engels explained that the task of the

emancipation of the working class was the task of the working class

itself. If the Marxists were going to influence the workers’ movement,

they should not set up their own sectarian barriers, but participate in

the real movement and go through the experience shoulder to shoulder

with the workers. Marx and Engels outlined this clear approach long ago

in the Communist Manifesto.

“The Communists do not form a separate party opposed to other working

class parties.“They have no interests separate and apart from those of the

proletariat as a whole.“They do not set up any sectarian principles of their own, by which

to shape and mould the proletarian movement.“The Communists are distinguished from the other working class

parties by this only: 1. In the national struggles of the proletarians

of the different countries, they point out and bring to the front the

common interests of the entire proletariat, independently of all

nationalities. 2. In the various stages of development which the

struggle of the working class against the bourgeoisie has to pass

through, they always and everywhere represent the interests of the

movement as a whole.” (Marx and Engels – Selected Works, vol.1,

pp.119-120)

Independent party of labour

Marx and Engels welcomed the steps taken by the working class to

break from the old capitalist parties and establish their own

independent party of labour. Every real advance for the labour movement,

explained Marx, was more important than a dozen correct programmes.

In Britain, the Marxists in the Social Democratic Federation (formed

in 1881) correctly helped found the Labour Party, along with the trade

unions, the Independent Labour Party and the Fabians. Despite the fact

that the Labour Party was ideologically weak, it was a real step

forward. Its task was seen as simply representing the interests of the

working class in Parliament. However, the failure of the SDF to secure a

resolution committing the Labour Party to socialism and “the common

ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange”

resulted in them walking out within the first year. It was an impatient

childish protest that simply strengthened the hold of the right wing

over the Labour Party.

While the SDF (later called the British Socialist Party) “withered on

the vine” in isolation, the Labour Party grew in size and influence.

The demise of the SDF was the fruit of their sectarianism. Today, they

exist as a historical fossil in the form of the Socialist Party of Great

Britain, as ineffective and sectarian as they were 100 years ago.

Marxism in their hands was reduced to a sterile dogma.

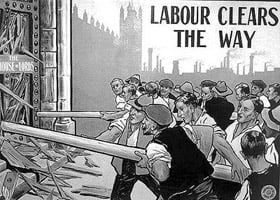

1909 election poster.If

they were genuine Marxists, they would have stayed and patiently put

forward their views. As was later shown, under the hammer blow of

events, the rank and file workers in the Labour Party adopted a new

socialist Constitution in 1918, containing the famous Clause Four, “To

secure for the workers by hand or by brain, the full fruits of their

industry based upon the common ownership of the means of production,

distribution and exchange…” On the basis of patient work, the SDF

could have built up a large influence within the Labour Party. They

chose instead to abandon the struggle. It was the mighty events of the

Russian Revolution of 1917 that changed the outlook of the British

workers and convinced them of their socialist aims.

Even prior to the adoption of Clause Four, the Labour Party had

affiliated to the Second (Socialist) International in 1908. The

affiliation was accepted by the International Bureau on a proposal of

Karl Kautsky, the then leading Marxist theoretician, and supported by

Lenin. In the debate, Lenin viewed the British Labour Party not as party

based on socialism and class struggle but as representing “the first

step on the part of the really proletarian organisations of

Britain towards a conscious class policy and towards a socialist

workers’ party.” (Lenin on Britain, p.97) Although the party was still

tied largely to the coat-tails of the Liberals, Lenin was convinced that

this would change following this “first step” on the basis of

experience and the powerful class instincts of the British trade unions.

In August 1914 the leaders of the Second International came out in

support of the imperialist world war. This betrayal of international

socialism came as a devastating blow. In Britain, the Labour leaders

entered the war-time coalition government. The horrors and chauvinism of

the War was however cut across by revolution in Russia. The October

Revolution changed the course of history, provoking revolutionary

situations everywhere and serving to bring the War to an end.

Unfortunately these revolutionary opportunities – in Germany, Hungary,

and elsewhere – were derailed by the old Social Democratic leaders. In

Germany, the Social Democrats even conspired to murder the Communist

leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

The Second International was dead. In order to fight for the

socialist revolution, Lenin called for a new Third International to be

created and the establishment of new mass Communist Parties. Given the

political ferment at the time, mass Communist Parties were created in

Germany, France, Italy, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Norway. As you

might expect, they were not born out of small sects, but arose from the

traditional mass organisations of the workers. For example, in France at

the Tours Congress in December 1920, the majority of the Socialist

Party voted to change its name to Communist Party and affiliate to the

Third International. This was similar in Germany where the Independent

Social Democracy (USPD) came over lock, stock and barrel to the new

International. In Italy the Communist Party emerged from a mass split –

one third of the membership in the Socialist Party in 1921 after the

treacherous role of the reformist leaders in the 1920 factory occupation

movement. The Social Democratic parties in many countries, either

through mass splits or as whole parties, passed over to the Communist

International.

One of the key exceptions was in Britain. The British Communist Party

did not emerge from the Labour Party. There was no split or mass

desertion. The CP was formed out of a small conglomeration of groups and

individuals, numbering only a few thousand, many of them with a very

sectarian outlook, a left-over from the days of the SDF.

The same problem of sectarianism, but on a much larger scale, had

appeared in most of the leaderships of the new Communist parties, which

were young and inexperienced. They lacked the theoretical grounding and

experience of the leaders of the Russian party. They therefore made

mistakes, some serious, mainly of an ultra-left character in the first

period.

The weak situation of the British CP was debated at the Second

Congress of the Third International in the summer of 1920. On the agenda

was a proposal that the British party apply for affiliation to the

Labour Party. Lenin gave support to this idea in order for the

Communists to get close to and hopefully influence the rank and file of

the Labour Party. This position, however, was opposed by many of the

ultra-lefts in the British CP, such as Willie Gallacher and Sylvia

Pankhurst.

Left-wing Communism

Lenin wrote a book against their arguments entitled Left-wing

Communism, an Infantile Disorder. These ultra-left moods,

reflecting impatience and inexperience, were widespread among sections

of the Communist International. The usual manifestations were a

rejection of parliamentary work, a refusal to work in reformist trade

unions, and a sectarian attitude to the mass reformist parties.

Lenin and Trotsky combated these ideas by advocating the United Front

with other workers’ organisations as a means of creating a bridge to

the mass of Social Democratic workers who were still a majority in most

countries. This meant links with the Labour Party in the case of Britain

The split to form separate Communist Parties was not about sectarian

principles or an act of salvation, but of winning the mass away from

national chauvinism. The point now was to influence the Social

Democratic workers who remained behind in the direction of socialist

revolution. As we see in the case of Britain, Lenin went much further in

this idea, given the numerical weakness of the British Communists,

advocating that the CP should try to affiliate to the Labour Party.

Willie Galacher, leader of

the Clyde Workers’ Committee.Left-Wing Communism was

written as an answer to the ultra-lefts, whose arguments re-appear at

every stage in the propaganda of the sects – even today. Lenin explained

that it was a crime to split away the advanced workers from the mass,

and that such tactics, far from undermining the labour and trade union

bureaucracy, actually serves to strengthen it.

Willie Gallacher was leader of the Clyde shop stewards and was keen

to establish a Communist Party in Britain. He travelled to Moscow for

the Second Congress and had personal discussions with Lenin.

“I was an outstanding example of the ‘Left’ sectarian and as such had

been referred to by Lenin in his book Left-Wing Communism, an

Infantile Disorder”, explained Gallacher in his memoirs. “I was

hard to convince. I had such disgust at the leaders of the Labour Party

and their shameless servility that I wanted to keep clear of

contamination.”“Gradually, as the discussion went on, I began to see the weakness of

my position. More and more the clear simple arguments and explanations

of Lenin impressed themselves in my mind.” (Revolt on the Clyde,

p.251)

Many in the young CP in Britain (formed in August 1920) had similar

ultra-left views to Willie Gallagher. As a result, the CP only voted by a

narrow margin 100 to 85 in favour of Labour Party affiliation. Their

first application was couched in such terms as to invite rejection. When

rejection came, the leadership’s relief was expressed in their paper, The

Communist of 16 September 1920: “So be it. It is their funeral,

not ours.”

It took the patient intervention of Lenin and Trotsky to curb this

ultra-leftism and steer the party on to a correct course towards the

unions and the Labour Party. Once corrected, this allowed the young CP

to build up a significant base in the Labour Party. While the Labour

leaders rejected their affiliation, CP members were allowed to be

individual members and participate within the Labour Party, including as

delegates to Labour’s national conference.

In elections, the young CP was advised to put up candidates in a few

safe Labour seats where there was no risk of splitting the vote and

letting in the Tories and Liberals, and giving critical support to the

Labour candidate in all other areas. Several CP members even stood as

official Labour candidates. Shapurji Saklatvala was elected as MP on a

Labour ticket in Battersea North in 1922. By the mid-1920s, despite

bureaucratic rule changes to exclude Communists, a whole number of local

Labour Parties were under Communist influence.

Where is Britain going?

Leon Trotsky had followed events in Britain and wrote a book called Where

is Britain Going? in 1925. The book’s content, which is strikingly

modern, has a clear bearing on today’s situation. It deserves to be

read by all those who want to understand what is happening in Britain

today.

“Throughout the whole history of the British Labour movement there

has been pressure by the bourgeoisie upon the proletariat through the

agency of radicals, intellectuals, drawing-room and church socialists

and Owenites” (early British socialists) “who reject the class struggle

and advocate the principle of social solidarity, preach collaboration

with the bourgeoisie, bridle, enfeeble and politically debase the

proletariat.” (p.48)

However, in predicting events that would unfold over the following

six years, including the 1926 General Strike, Trotsky wrote:

“The mole of revolution is digging too well this time! The masses

will liberate themselves from the yoke of national conservatism, working

out their own discipline of revolutionary action. Under this pressure

from below the top layers of the Labour Party will quickly shed their

skins. We do not in the least mean by this that MacDonald will change

his spots to those of a revolutionary. No, he will be cast out…. The

working class will in all probability have to renew its leadership

several times before it creates a party really answering the historical

situation and the tasks of the British proletariat.” (p.42)

At that time, he explained that:

“The Liberal and semi-Liberal leaders of the Labour Party still think

that a social revolution is a gloomy prerogative of continental Europe.

But here again events will expose their backwardness. Much less time

will be needed to turn the Labour Party into a revolutionary one than

was necessary to create it.” (Trotsky on Britain, vol.2, p.38)

Revolutionary transformation

While this revolutionary transformation of the Labour Party did not

come about, the crisis in the Party at the end of the 1920s and 1930s,

especially the ILP split in 1932, provided ample opportunities for such a

development. Unfortunately, ultra-left mistakes cut across this

potential.

Throughout the book, Trotsky regarded the Labour Party as the

“political section” of the British trade unions. The connection was a

class issue. So much so, that he regarded the payment of the political

levy to the Labour Party as a principled question. He went on to explain

that those who refused to pay the levy should be regarded as “political

strike-breakers”, who should be forced to pay:

“The struggle of the trade unions to debar unorganised workers from

the factory has long been known as a manifestation of ‘terrorism’ by the

workers – or in more modern terms, Bolshevism. In Britain these methods

can and must be carried over into the Labour Party which has grown up

as a direct extension of the trade unions.” (p.101)

The growing Communist influence within the Labour Party during the

mid-1920s was completely cut across by the degeneration of the Soviet

Union and the rise of the Stalinist bureaucracy, which played havoc with

the still immature leaderships of the Communist movement

internationally. The ultra-left zigzags of the Stalinists led to the

launching of the “Third Period” and “social fascism” in 1928. It was

based on the theory that capitalism was in its final stages and the

Communists had to separate themselves in the most ultra-left manner

possible from all other workers’ parties. The worst result was in

Germany, where the insane policy of “social fascism” split the powerful

German labour movement and allowed Hitler to come to power in 1933.

In Britain, the CP denounced the Labour Party as a “social-fascist”

party and advocated that its meetings be attacked and broken up. Such

hooliganism resulted in the utter isolation of the CP from the labour

and trade union movement. Any influence it had in the Labour Party

vanished overnight.

The world slump of 1929-33 and the rise of fascism in Germany had a

massive impact on the British Labour movement, especially the Labour

Party. A minority Labour government had come to power in 1929 and, due

to the capitalist crisis, had made cuts in the budget. By 1931 the

government collapsed, with the failure to carry out further cuts. Ramsay

MacDonald left the party to head a National Government. This betrayal

pushed the Labour Party far to the left.

The left wing gathered round the Independent Labour Party (ILP),

which had been an integral part of the Labour Party ever since its

foundation. Events created a deep ferment and propelled the ILP even

further to the left, with its leaders making very revolutionary sounding

speeches. The ILP became what Marxists term “centrist” in character,

i.e. half-way between Marxism and reformism. In 1932, the ILP tragically

decided to split from the “reformist” Labour Party with some 100,000

supporters.

Trotsky, who had been expelled by Stalin from the Communist

International, took a great deal of interest in what had been happening

in the ILP. Given his leading role in the Russian Revolution he still

had tremendous authority internationally. He personally contacted the

leaders of the ILP to offer advice. He thought the split from the Labour

Party was a mistake, carried out “at the wrong time and over the wrong

issue”. Nevertheless, he saw this break with reformism as an opportunity

to build a genuine revolutionary party in Britain. As a result, Trotsky

urged his British supporters to join the ILP.

“I wrote a series of articles and letters of an entirely friendly

kind to the ILP people, sought to enter into personal contact with them,

and counselled our English friends to join the ILP in order, from

within, to go through the experience systematically and to the very

end.” (Writings 1935-36, p.365)

Leon TrotskyTrotsky’s

advice to the ILP leaders was three-fold: 1) work out a genuine Marxist

policy; 2) turn your backs on the ultra-left Stalinists and face

towards the trade unions and the Labour Party; 3) join the new

International.

Even though the ILP had a considerable base amongst the advanced

workers, Trotsky insisted that they still face towards the Labour Party,

which remained the mass party of the working class. “It remains a fact

about every revolutionary organisation in England”, he wrote, “that its

attitude to the masses and to the class is almost coincident with its

attitude towards the Labour Party, which bases itself upon the trade

unions.”

“While breaking away from the Labour Party, it was necessary

immediately to turn towards it”, explained Trotsky (Writings on Britain,

vol.3, p.94). Brushing aside the objections of the ILP leaders, he went

on to argue for work within the party. “The policy of the opposition in

the Labour Party is unspeakably bad. But this only means that it is

necessary to counterpoise to it inside the Labour Party another, a

correct Marxist policy. That isn’t so easy? Of course not!” (Writings

1935-36, pp.141-142) Nevertheless, explained Trotsky, Marxists cannot

abandon such an essential task because of certain difficulties being

placed in their path by the bureaucracy. If that were the case, then one

may as well abandon all attempts to change society using “difficulties”

as a pretext for abandoning any revolutionary work.

The centrist leaders of the ILP chose to ignore Trotsky’s advice,

making ironic remarks about “dictators from the heights of Oslo”, a

reference to Trotsky’s place of exile in 1935. In the meantime, the

Labour Party recovered from the 1931 betrayal by MacDonald and moved to

the left in opposition. In practice, the mass of workers now could not

see a fundamental difference between the policies of Labour and the ILP

and, in such a situation, they inevitably rallied to the much larger

party. The ILP dwindled in size and eventually drifted back to the

Labour Party on a purely reformist basis. The attempt to create an

alternative revolutionary party failed.

ILP failure

After the ILP failure, Trotsky advised his supporters to enter the

Labour Party. This new tactic became generally known as “entrism”, and

was adopted in conditions of acute crisis of capitalism and where

centrist currents had emerged. The perspective was one of a rapid

movement towards either revolution or counter-revolution and one where

the task of building a genuine revolutionary Marxist party was of

paramount importance. Such a short-term tactic, based on Trotsky’s

perspective of the 1930s as a decade of revolution and counter-, is not

suitable for today’s work in the Labour movement.

In all of Trotsky’s writings on these questions we see a rounded-out

dialectical approach. He clearly did not view the mass organisations as

something fixed and static, but in their real development and internal

contradictions. Under conditions of convulsive crisis, it was

unthinkable that the traditional mass organisations of the working class

could remain unaffected. The tendency towards polarisation between the

classes inevitably finds its echo in the workers’ organisations. At a

certain point, this process gives rise to mass left reformist currents,

even centrist ones as with the ILP. Under these conditions, the ideas of

Marxism would find a ready-made mass audience. This is the historical

justification for patient work in the mass organisations.

Trotsky’s writings on the mass organisations are an important

heritage. They provide so many pointers. “What is … dangerous is the

sectarian approach to the Labour Party”, he explained (Writings on

Britain, p.144). Rather than waste one’s time in small splinter groups

on the fringes of the labour movement, it was important to get involved

in the mass organisations.

“A revolutionary group of a few hundred comrades is not a

revolutionary party and can work most effectively at present by

opposition to social patriots within the mass organisations. In view of

the increasing acuteness of the international situation, it is

absolutely essential to be within the mass organisations while there is

the possibility of doing revolutionary work within them. Any such

sectarian, sterile and formalistic interpretation of Marxism in the

present situation would disgrace an intelligent child of 10.” (Writings

on Britain, vol.3, p.141)

Counter-reforms

Despite these essential writings, different “Marxist” groups have

made one mistake after another on this key question. Towards the end of

the 1960s, a number of left groups abandoned work in the Labour Party in

disgust at the counter-reforms of the then Labour government. They

wrote off the party and set about building their own independent

revolutionary parties, ignoring everything that had been written on the

importance of the mass organisations. The more isolated they were, the

more ultra-left they became. Rather than connect with the real movement,

they continually sought to tear the advanced workers away from the

mass. They saw their prime task as to “expose” the leadership through

shrill denunciation. This has been the hallmark of all these different

sectarian groups. With such antics they end up playing into the hands

and reinforcing the position of the right-wing leaders.

Some on the left object to being described as sects, but this is not a

term of derision but a scientific definition. According to Trotsky,

“Sect is a term I would use only for an organisation of a kind that is

forever doomed, by virtue of its mistaken methodology, to remain on the

sidelines of life and of the working class struggle.” (Writings 1930,

p.383). What is the common error of these groups? “Each sectarian wants

to have his own labour movement. By the repetition of magic formulas he

thinks to force an entire class to group itself around him. But instead

of bewitching the proletariat, he always ends up by demoralising and

dispersing his own little sect.” (Writings 1935-36, p.72) This whole

approach is the complete opposite of Marxism, as can be seen from the

method outlined in the Communist Manifesto. It is also not

necessarily a question of size that determines the sectarian nature of a

group, but of a correct orientation to and relationship with the

working class and its organisations.

The only Marxist group that made any real impact in the Labour Party

was the Militant tendency, founded by Ted Grant in 1964. Ted

had explained that what was needed was consistent patient work in the

mass organisations. We needed to develop a Marxist tendency as an

integral part of the Labour Party, as was originally the case.

As a result, and in complete contrast to the sects, the Militant

patiently built up its position throughout the 1960s and 1970s,

especially within the ranks of the Labour Party’s youth section, the

Labour Party Young Socialists. Their whole approach was different in

that they regarded themselves as part of the labour movement, despite

having distinct ideas and programme. As a result, their influence grew

throughout these years together with the general development of the

left. They were able to connect with the working class, beginning with

the active layer in the ward Labour Parties, the shop stewards

committees, the trade union branches, and in the Young Socialists. Their

consistent energetic work in the party allowed them to go from a

monthly paper to a weekly, politically dominate the LPYS, achieve the

election of three Militant-supporting Labour MPs, and become

recognised as a serious tendency in the labour movement. In Liverpool,

by the early 1980s, Militant had established a huge influence

in the newly-elected Liverpool City Council.

Right-wing attacks

Neil Kinnock speaking in

2007. Photo by dushenka.With success came the orchestrated

attacks of the right wing. A witch-hunt was launched by the capitalist

media against the “Trotskyist infiltrators” in the Labour Party. Their

aim was to use the witch-hunt against Militant to undermine the

swing to the left in the party. By 1983, the editorial board of Militant

was expelled. After Kinnock’s attack on Militant at the 1985

party conference, further expulsions followed. Along with Lambeth,

Liverpool Council was isolated and the councillors surcharged and

disqualified. Together with the defeat of the miners, this marked a

sharp shift to the right in the Labour movement. This was followed by

the effective closure of the LPYS and further organisational measures

taken to proscribe the Militant.

In contrast to the militant struggles of the 1970s, the 1980s (with

the notable exception of the miners’ strike) was a period of retreat.

The workers’ organisations emptied out and the left, which had been

powerful in the previous period, collapsed. It is clear that the boom of

1982-90 played a key role in these developments, providing a material

basis for these changes.

Revolutionary tendencies do not exist in a vacuum. They are subject

to the pressures of capitalism, as with the class as a whole. The

disorientation and confusion of the left generally, compounded by the

collapse of Stalinism in 1989-91, had an effect on the Militant

tendency. This led to impatience and frustration amongst a majority of

its leaders, who, despite everything, lost their bearings.

Shortcuts

They began to look for a short-cut to success and decided to break

from the Labour Party and establish their own party, which eventually

became the Socialist Party. The idea that a small organisation of a few

hundred, or even a few thousand, could compete with the Labour Party was

ludicrous. Trotsky considered the ILP, a sizeable organisation with its

100,000 supporters, a sect in the conditions of the British labour

movement.

The Socialist Party abandoned its previous orientation and moved

towards ultra-leftism, little different from the other groupings on the

fringes of the labour movement. Consequently, rather than increase its

size, its membership declined significantly. This led them further down

the road of ultra-leftism by calling on the affiliated trade unions to

disaffiliate from the Labour Party and instead form a new workers’

party. This call to break the union-Labour link is sheer adventurism. It

mirrors the same call of the extreme right around the Blairites, who

wish to see the Labour Party transformed into a bourgeois party. They

have in fact written off the Labour Party as simply another capitalist

party no different from the Tories or Liberals. They then call on

workers not to vote Labour “as they are all the same”. This is a

fundamental mistake as, despite its pro-capitalist leadership, the

Labour Party rests on the trade unions. This, in the last analysis,

defines its class character.

Trotsky answered this argument long ago:

“It is argued that the Labour Party already stands exposed by its

past deeds in power and its present reactionary platform. For us – yes!

But not for the masses, the eight million who voted Labour.” (Writings

on Britain, vol.3, pp.118-19)“The Labour Party should have been critically supported… because it

represented the working class masses.” (ibid, p.117)

In the recent period there have been numerous attempts to establish

parties to the left of Labour, all of which have utterly failed. Arthur

Scargill, the leader of the miners during the 1984-85 strike, set up the

Socialist Labour Party in 1996 in protest at the abandonment of Clause

Four. Despite the stature of Scargill, the party sank without trace.

In Scotland, the Scottish Socialist Party was set up, gained six MPs

in the Scottish Parliament, but then lost them, split and in effect

collapsed. The illusion that it could become the second workers’ party

in Scotland evaporated. In the recent general election, it won only

3,157 votes across 10 constituencies, averaging 315 votes per candidate.

This was less than the poor showing in the previous election of 2005.

In England, the Socialist Alliance was tried, and then came Respect.

All these efforts were based on opportunist politics, either pandering

to nationalism in Scotland or to communalism in the Muslim community.

Despite claims to the contrary, Respect was consciously trying to

present itself as a “Muslim party”. The success in winning a single

parliamentary seat in Tower Hamlets was short lived as the party split

and then lost its seat in the recent general election, coming third

after the Tories. The party has little future, being confined to a few

geographical areas.

“Socialist Alternative”

The SP won a few local councillors over the last decade under the

name Socialist Alternative. In Coventry, Huddersfield, and Lewisham,

where they held five council seats, they lost them all bar one to

Labour. This was held by Dave Nellist because of a personal following

based on his past position as the Labour MP in Coventry South East. Now

he is on his own on the council without a seconder for his proposals.

This followed on from the debacle in last year’s Euro elections, when

the SP along with others stood as the No2EU campaign. Despite backing

from Bob Crow and the RMT, they managed to scrape together only 1% of

the vote. The programme they stood on was completely nationalistic and

reformist. It was an attempt to opportunistically water down their ideas

to win more votes, but failed miserably.

In the recent general election, there was the formation of the Trade

Union and Socialist Coalition. This time, there was no national trade

union endorsement, only individuals. The result was worse than in 2009.

If you take all the votes for the 40-odd TUSC candidates, the combined

vote was only half of the vote achieved by left Labour MP John McDonnell

in Hayes and Harlington. After all the effort and money poured in, this

is what they managed to achieve – 1% of the vote. The Labour Party,

despite 13 years of New Labour government, still managed to poll

8,600,000 votes.

Left-wing Labour MP John

McDonnell speaking at a Hands Off Venezuela meeting.According

to them, if there was ever a time when the groups standing to the left

of Labour should have done well it was now. They said Labour was

discredited and offered the true alternative. But when it came down to

it, they were completely ignored in the election.

Although TUSC fielded some very good class fighters, this made no

difference. In Swansea West, Rob Williams stood. He is the convener of

the former Fords plant in Swansea and was victimised last year, but

reinstated after threats of strike action. Despite this, he was able to

pick up only 179 votes. He came ninth out of nine candidates, bottom of

the poll. Labour (described by Rob as the “capitalist party”) won the

seat with over 12,000 votes. In Coventry North East, Dave Nellist, the

former Labour MP and the most well-known TUSC candidate, managed to

scrape 1,592 votes (3.7%), but the Labour candidate got over 21,000

votes (49.3%). The vote for Dave, who was expelled from the Labour Party

in 1992, has gone down at every election since. In 1992 he polled

10,500 votes, while today it is down to 1,600, even less than the BNP.

This speaks volumes about the loyalty of the working class towards the

Labour Party. The attempt to create an alternative to Labour on the

electoral front has once again failed.

“But to those who dismiss our small votes, we say that Keir Hardie

and the Independent Labour Party received similar figures and derision

in their attempts to break the trade unions from the Liberals at the end

of the nineteenth century”, states the SP leaflet handed out at the

June UNITE conference. “We will not be deterred from advocating a new

mass workers’ party that reflects the labour movement’s aims and

policies.”

Keir Hardie

What the SP leaders fail to understand is that when Keir Hardie stood

in elections, there was no established Labour Party. Today a Labour

Party exists – whether we like it or not supported by millions of

workers as the general election shows. To believe that workers will seek

to establish a new party, without at first attempting to reform the

old, is to forget all the lessons of history. If after 13 years of

pro-capitalist policies of New Labour, workers show no intention of

breaking with the Labour Party, this shows precisely the deep roots the

party has in the working class. “Mass organisations have value precisely

because they are mass organisations”, explained Trotsky. “Even when

they are under patriotic reformist leadership one cannot discount them.”

(Writings 1935-36, p.294). And again, “If a worker barely awoken to

political life seeks a mass organisation, without distinguishing as yet

either programmes or tactics, he will naturally join the Labour Party.”

(Writings on Britain, vol.3, p.93). And finally, “workers do not leap

from organisation to organisation with lightness, like individual

students.” (Ibid, p.53)

Keir HardieThe

first task, as part of attempting to change society, is to understand

what is. The ascendency of the right wing in the past period was based

on the boom of capitalism, albeit a boom based on credit and

speculation. That has now collapsed. A new period of storm and stress is

opening up in Britain and internationally. Events will propel the

working class into action, at first on the industrial front, then on the

political front.

As the Marxist tendency has explained many times, the working class

will take the line of least resistance and when it moves politically it

will move towards its traditional mass organisations. When this happens,

all those groups on the fringes of the movement will be left high and

dry. The main struggle for the future of society will be fought within

the Labour Party and the trade unions. On the basis of events, the right

wing will be squeezed out and the left will be in the ascendency. It is

the task of Marxism to “patiently explain” and fertilise this left wing

with revolutionary ideas. Before the ideas of scientific socialism can

conquer the broad mass of the working class, they need to politically

conquer the mass organisations. The mistakes and isolation of the

Marxists in the past, due mainly to their sectarianism, has been both a

tragedy and a farce. We need to learn from history and understand that

there is no short cut to the masses “At all costs we must be careful to

avoid either sectarianism or opportunism”, explained Trotsky (Writings

on Britain, vol.3, p.138).

The ruling class has maintained a firm grip on the Labour Party

through its right-wing agents. Their task was to make the party safe for

capitalism. They were able to accomplish this in the past period

largely due to the boom built on credit. That has now come to an end.

The crisis of capitalism is reflected in the demands for austerity

everywhere. As a consequence, we are heading for huge clashes between

the classes not seen in generations. Such a situation will radicalise

the working class and serve to transform the labour movement. This will

also shake the Labour Party from top to bottom.

Enormous opportunities

Enormous opportunities will open up for the Marxist tendency as our

ideas increasingly connect with the radicalised workers and youth. They

will look towards the mass organisations to solve their problems. We

will go through the experiences with them shoulder to shoulder,

explaining the need for the socialist transformation of society.

Whatever measures are taken by the bureaucracy, they will not succeed in

breaking the links between Marxism and the organised working class.

On the basis of, “patiently explaining” our ideas, in a friendly and

sober tone, we can win over the majority of class-conscious workers and

youth. In doing so, we can help to transform and retransform the mass

organisations and change them into genuine vehicles to change society.

We appeal to all workers and youth to join us in this fight.

“We are fighting for genuine scientific ideas and principles, with

inadequate technical, material, and personal means. But correct ideas

will always find the necessary corresponding means and forces…”,

explained Trotsky. “There was never a greater cause on earth.”