The ideas of Feminism have traditionally found support in universities, and these ideas are currently enjoying a surge in popularity amongst students. Continuing our series of articles to celebrate International Women’s Day – 8th March – we publish an article from the Marxist Student Federation, which looks at the ideas of Marxism and Feminism in relation to the student movement.

The ideas of Feminism have traditionally found support in universities, and these ideas are currently enjoying a surge in popularity amongst students. At a time when the ideas of Marxism are also finding a growing echo in the student movement, what attitude do Marxists take towards different feminist ideas? How far are these schools of thought compatible? What are the points of contention between them? And what does it mean to call yourself a “Marxist-Feminist”?

Marxists, like feminists, fight to end the oppression of women, as part of a struggle against all forms of oppression. The utopian socialist Flora Tristan pointed out in the first half of the 19th century that the struggle for the emancipation of women is inseparably bound up with the class struggle. Marx and Engels included some of Tristan’s ideas in The Communist Manifesto, and Engels went on to write Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State, which uses anthropological evidence to explain the origins of the oppression of women and how it can be overcome.

The founder of the German Social Democratic Party, August Bebel, further studied the question of women’s oppression in his book Women under Socialism and Leon Trotsky developed this in his series of essays Women and the Family. Towering figures in the socialist movement such as Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin and Alexandra Kollontai proved in practice the power of socialist struggle to break down sexist prejudice. The role of women workers in Petrograd in February 1917, the East London matchgirls in 1888, and the miners’ wives in 1984-5 are some of the better known out of countless examples of the key role that working women have played in the class struggle. Most significantly, the achievements of the Bolsheviks in the first years after the 1917 revolution demonstrate the possibilities that socialism presents for ending the oppression of women.

Class struggle

These and other practical successes of Marxism on the question of the oppression of women can be put down to the inseparable link between the labour movement and the struggle for socialism. As Marx and Engels point out: “[t]he history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle”.

The battle between exploited and exploiter – a relationship defined by each individual’s position in the economic process – ultimately governs the ideology, institutions and prejudices of any given society. It is therefore to the existence of class society we must look for the origins of sexism, rather than to supposed inherent traits in either men or women. For this reason Marxists intervene in this class war, on the side of the exploited, to challenge the conditions of exploitation and the various forms of oppression, including sexism, to which they give rise.

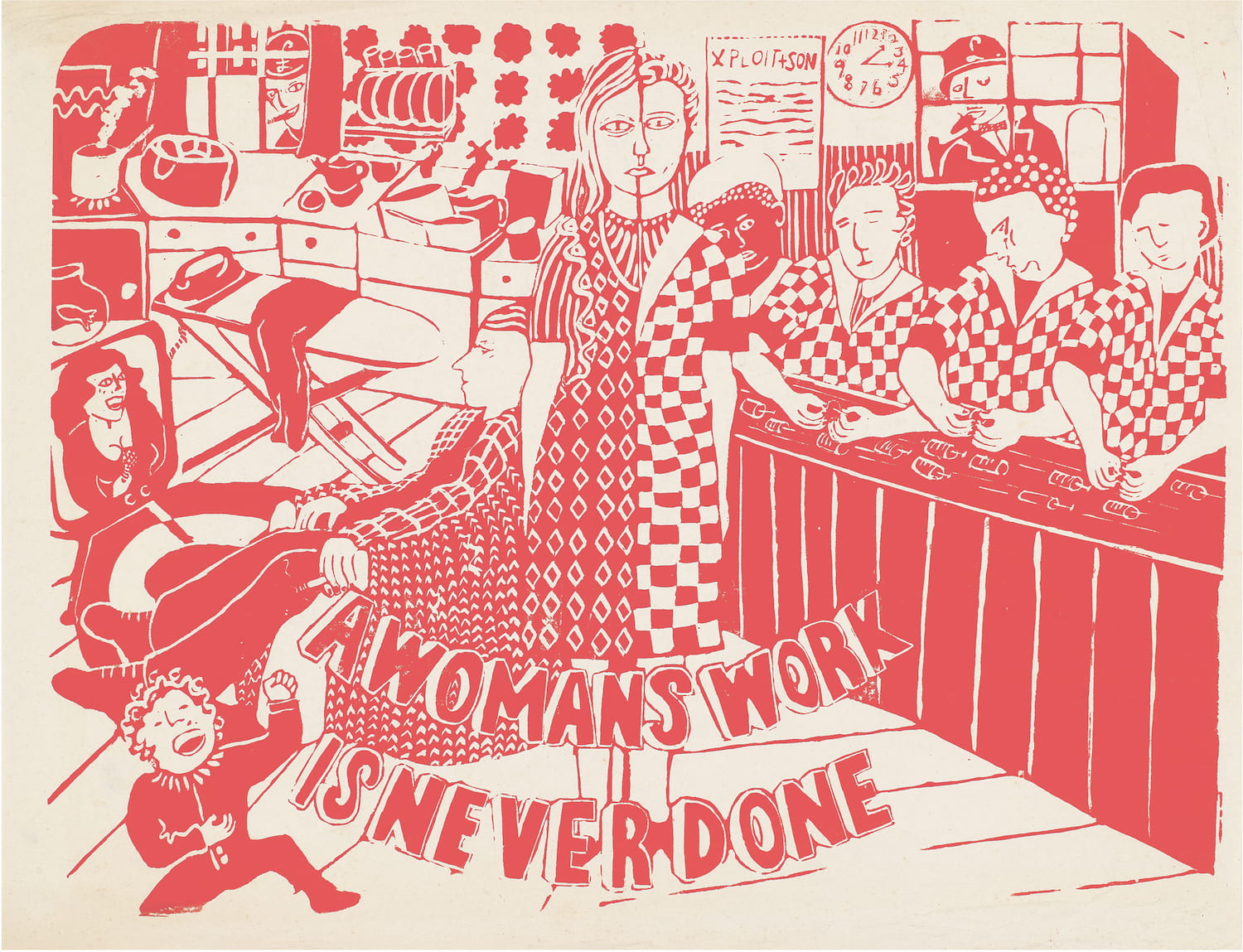

So how does the modern form of class society – capitalism – perpetuate sexist prejudice and the oppression of women? Capitalism relies on the family as the primary economic unit and therefore relies on the oppression of women in society to provide free labour in the home. It also uses low-paid women to drive down wages and conditions for the entire working class.

Marxists therefore argue for socialism, which would allow for the socialisation of domestic labour and would put a stop to exploitation via wage labour – as was proved in Russia after 1917. In other words, the struggle for socialism removes the material basis for the oppression of women. This struggle can only be carried out by the working class as a whole, due to their position in production, and so Marxists immerse themselves in the class struggle, intervening in the movements and mass organisations of workers and youth, to end the exploitation of the proletariat and the oppression of women.

Positive discrimination

This is not the attitude towards the trade unions, political parties, student unions and other organisations of working class struggle is not shared by some feminists. For example, Anna Coote and Beatrix Campbell, in their book “Sweet Freedom: The Struggle for Women’s Liberation”, describe trade unions as part of the “patriarchal system”, calling strikes an outdated “dispute practice”. Instead of demanding that workers as a whole take a larger share of the wealth in society, Coote and Campbell argue simply for equality in wages between men and women. And rather than challenging the union bureaucracy, which stifles workers’ attempts to win higher wages, they simply call for more female bureaucrats.

Many of the leading bodies of these organisations are dominated by men, which is a reflection of the oppression of women in society as a whole. Manyfeminists therefore demand equal numbers of men and women at the top of these institutions as a means by which to promote gender equality, a policy strongly backed by Harriet Harman, Deputy Leader of the Labour Party. The result is a drive for positive discrimination in unions and parties, with a minimum number of elected positions and a certain amount of speaking time in meetings reserved for women.

Such methods turn the problem on its head. It is not the male dominance of student unions, trade unions, political parties or other mass organisations that fuels the oppression of women – it is the sexist prejudice inherent in class society that causes male dominance of unions. The unions, by uniting the working class, can be used to smash that class society and are therefore a means to the end of eliminating women’s oppression. Creating an ideal model union that is “pure” and free from prejudice is not an end in itself – in fact such a model union can never exist so long as society as a whole is not fundamentally changed.

In reality these methods can actually be counter-productive. Unions and political parties can only be effective weapons against the oppression of women and other prejudices if they are led by staunch working-class activists and pursue bold socialist policies – qualities which are not exclusive either to men or to women.

To achieve this, leaders need to be elected on the basis of their politics not their gender, and internal debates need to be determined by the political content of the speeches not the gender of the person giving the speech. Margaret Thatcher’s politics were not defined by her gender but by her class. The same goes for the German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the head of the IMF Christine Lagarde. The ideas of these people spell nothing but misery for all workers, particularly women, and in the eyes of the working class they do not gain an ounce more validity simply because they are espoused by a woman instead of a man.

As any activist will know, and as history has proved, winning the political struggle for revolutionary ideas inside mass organisations of the working class, such as unions or parties, is not easy. It requires consistent, patient work winning people over to clear political ideas with a theoretical basis. Every step towards revolutionary socialist ideas in working class organisations is a precious gain.

Those who advocate policies of positive discrimination threaten to undermine this work by replacing socialist aims and the methods necessary to achieve them, with the legalistic aims and methods of formal gender equality which, by their nature, lack political clarity and a theoretical base. It is the difference between a political struggle for ideas that can emancipate the working class as a whole, and a struggle for the reorganisation of the bureaucracy inside unions and political parties. Quite clearly one of these has the revolutionary potential to fundamentally change society while the other one offers nothing but improved career prospects for a small layer of potential bureaucrats. These struggles are entirely different and do not complement each other – the latter can only detract from the former.

As Marxists we do not focus our attention on the organisational structure of union bureaucracy. We are interested in winning the rank and file students and workers to the ideas of socialism. Bureaucracy is, in fact, the very antithesis of the rank and file of the working class. It acts as a brake on the movement, rendering the workers’ organisations less responsive to the changing consciousness and needs of the workers themselves by elevating officials away from the conditions of ordinary people.

We only need to look at the leadership of trade unions, and especially the Labour Party, today to see this process taking place. That the bureaucracy plays this role is not due to its majority male composition, and it would not cease to be a drag on the movement simply by installing more female bureaucrats. Putting our energy into campaigning for a “better bureaucracy” therefore actively undermines our fight for the revolutionary ideas of socialism and the emancipation of female and all workers that they offer.

Raising awareness

Few feminists claim that positive discrimination is all that is needed to achieve gender equality. In fact many feminists, like columnist Laurie Penny, are likely to agree that a fundamental change in society along class lines is indeed necessary to solve the problem. However, Penny and many others also argue that attacking the symptoms of the problem without attacking its root cause is still worthwhile because it raises awareness of the oppression of women. Such is the argument behind the Everyday Sexism project, the recent anti-‘Blurred Lines’ campaign and the No More Page 3 campaign – they are not designed to solve the problem of the oppression and objectification of women in society, but rather to raise awareness and win a small victory for women in these particular battles.

The problem with such campaigns is that they often sow illusions in methods and ideas which in fact offer no solution to the issues. Simply telling people that women are oppressed is not enough to prevent that oppression from happening. Raising awareness is only effective as part of a mass campaign to actually do something to tackle the problem. While there is no shortage of feminist academics and journalists raising awareness about women’s issues and coming up with ideas for how to eliminate the oppression of women, there are very few examples of mass campaigns to tackle the root cause of these issues. Those campaigns which do exist are limited to one instance of sexism in the media or in the music industry with no perspective of how to fight oppression as a whole.

Such narrow demands can actually allow for the accommodation of extremely reactionary points of view in these campaigns, such as the view of the founder of the No More Page 3 campaign who describes The Sun as a newspaper of which she is “proud” and that could be made even better with the removal of page three, despite the racist, homophobic, sexist and anti-working class bile that fills all the other pages of the newspaper. To have illusions in the power of these campaigns to solve the problems can divert good activists from the work of fighting for a revolutionary transformation of society.

Waiting for the revolution?

Does this mean that Marxists argue that women must simply wait for the socialist revolution for sexism to be challenged? Of course not. It is through the unity of the working class on the basis of a common class position, regardless of gender, race or sexuality, and fighting for common socialist aims that prejudice is broken down. The struggle for socialism is based on the power of workers – not male workers or female workers, but all workers. If such a struggle is waged, every worker will play a vital role and a victory of male workers will be impossible without an equal struggle on the part of female workers. The socialist economic system will smash the material base for the oppression of women, while the struggle to establish that economic system will tear down sexist prejudice by proving in action the equality of men and women.

For example, during the miners’ strike in Britain, it was after hearing the fiery speeches of the miners’ wives, witnessing their courage in the face of the Thatcher’s brutality, and relying on their fundraising abilities, that the male dominated miners’ organisations voted to remove sexist overtones from their union literature. Women came to be seen by the workers as staunch proletarian activists who commanded respect and were empowered to demand equal treatment. Such empowerment was not achieved simply by talking about it, but by actively building an organisation of working class men and women fighting for their rights.

Marxists are under no illusions that, come the revolution, we will immediately be living in an oppression-free utopia. The traditions of past ages weigh like a mountain on modern society. Class society and the oppression of women has existed for close to 10,000 years – such traditions can’t be shaken off in the blink of an eye. What is needed is a fundamental change to the way society is structured – not tinkering around the edges but to turn the whole system upside down. Only by shaking society to its roots can we hope to dislodge such an accumulation of rotten traditions. This is precisely the definition of socialist revolution – a permanent process that allows us to build a world free from these old prejudices.

It is therefore the task of all those who want to tackle the oppression of women to fight for socialist policies and mass campaigns in the labour and student movement. Both proletarian emancipation and gender equality lie along the path of working class unity and socialist revolution.

Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a school of thought stemming from feminism and which points out that all oppression is connected and so each person will experience different forms of oppression in different ways depending on how they are connected for that particular individual. For example the oppression experienced by a black working class woman is different to that experienced by a gay white man, which is different again to the experience of a straight disabled person, and so on. This observation is patently correct.

These ideas have existed for a long time, although they were significantly developed by the work of Kimberle Crenshaw in the early 1990s and taken even further by the sociologist Patricia Hill Collins. These people, and others who argue in favour of this view of oppression, are therefore opposed to the sectioning off of certain groups from the movement as a whole on the basis of gender, race, sexuality etc. They also introduce the idea of class as an important tool in analysing society and so in general appear to be closer to the ideas of Marxism than many traditional feminists; in fact Collins describes herself as standing in the “Marxist-Feminist” tradition.

However, in actual fact, intersectionality reduces oppression to an individual experience that can only be understood by the person suffering it. This is because every person experiences oppression in a uniquely different way and so it is only that individual who knows how best to fight it. This individualism serves to break apart mass movements into atomised individuals all fighting their own unique battles to which others can contribute little more than passive support. It is for this reason that intersectionality appears in the student movement as little more than a method of analysis. As a school of thought it is offers little towards building a mass movement for practical change.

Intersectionality fails to appreciate the qualitative difference between the experience of the working class (which obviously includes both men and women) and the experience of all women. Workers are not just oppressed – they are exploited as a class for the economic gain of the bourgeoisie. Women are not economically exploited as a class, because not all women belong to the same class. Women are oppressed by capitalism in order to facilitate the greater exploitation of the working class.

Thus Marxists argue that intersectionality is wrong to view class and gender as comparable factors in understanding society’s problems. Capitalism is motivated by the pursuit of profit via the exploitation of the workers – society under capitalism therefore moves in the grooves of the class struggle. The oppression of women is a consequence of this exploitation and can only be combatted as part of the struggle for the emancipation of the working class. While intersectionality offers isolated individualism, Marxism offers working class unity.

Feminism and democratic demands

The early ideas of feminism arose around figures such as Mary Wollstonecraft and demands for democratic rights: the right to vote, the right to abortion, the right to work and the right to equal pay. While in many countries these rights are yet to be won, in Britain there is almost no legislation that actively discriminates against women. Equality before the law has, largely, been achieved.

And yet women still suffer discrimination and oppression in society despite these democratic rights having been won. Thus modern feminists – from Harriet Harman to Laurie Penny – demand measures that go beyond formal legal equality, such as positive discrimination, or measures that don’t seek to introduce new rights, but that rather raise awareness about the rights that already formally exist.

The severe limitations of such policies have already been pointed out. What Marxists explain is that the demands of such strands of feminism are democratic demands – and bourgeois democratic demands at that. Taken alone, their vision for the world is one where men and women are oppressed and exploited equally under capitalism.

Not only is this gender equality an impossibility under capitalism, but even as an utopian idea this is not particularly inspiring. While liberal feminists want more women in the boardroom, Marxists want to get rid of the boardroom. Some feminists simply want men and women to share the housework equally, while Marxists want to socialise housework and ends its status as unpaid private labour.

As with all democratic demands, Marxists support feminist demands. However, we must point out the limitations of simply fighting for democratic demands without linking these to the question of socialist revolution. We must not let discussion on particular issues divert from the wider question of the socialist transformation of society.

For example, in her reminiscences, Clara Zetkin – the German communist and founder of International Working Women’s Day – recalls meeting Lenin in 1920 when they discussed the women’s question at length. Lenin congratulated her on her education of the German communists on the issue of the emancipation of women. However he pointed out that there had been a revolution in Russia that presented an opportunity to build, in practice, the foundations for a society free from the oppression of women. Given these circumstances, Lenin explained that the dedication of so much time and energy to discussions on Freud and the sexual problem was a mistake. Why spend time discussing the finer points of sexuality and the historical forms of marriage when the world’s first proletarian revolution is fighting for survival?

This is an example of a Marxist understanding of feminism and its demands. The issues facing working class women can be used to raise the consciousness of the working class as a whole, by illustrating the oppression of women under capitalism and the need for socialism to combat this. But we cannot let the fight for women’s liberation be an isolated movement that divides the working class. Marxists use the compass of the unity of the working class and the need to advance the struggle for socialism as our guide.

In countries like Britain, the bourgeois democratic demands of feminism have reached their limits, and in the student and labour movement it is now common to find discussions on organisational questions related to gender being used to distract from the need for a discussion on political questions.

Faced with the biggest fall in living standards since the 1860s, students and workers need to organise demonstrations, protests and strikes to defend their standard of living. And yet, as many who have been present at student union or activist meetings will know, a lot of time in such meetings is given over to discussions on “safe-spaces”, the appropriate use of pronouns (using “he” or “she” to refer to other people), debates over the percentages of gender composition among elected officials, and debates over which songs are sufficiently misogynistic to deserve a ban.

If these organisations and movements were instead discussing and committing to building serious and militant campaigns to win people over to the ideas of socialism and fight the atrocious austerity attacks (which, by the way, are hitting women particularly hard), then they would be able to unite students and workers in that same struggle, irrelevant of gender, race, sexuality or anything else. In this kind of struggle every person plays a vital part and no particular physical attributes are more or less preferable in the fight for socialism. It is in the heat of the class struggle that prejudices are broken down.

“Marxist-feminist”

Many young people, as a reaction to what they correctly see as the sexism of some political organisations – including some on the Left – call themselves Marxist-Feminists in order to emphasise their commitment to female emancipation as well as working class emancipation. This is a phenomenon that has been particularly prevalent in the USA since the late 1960s, spearheaded by such figures as Gloria Martin and Susan Stern of the Radical Women organisation.

However, for any genuine Marxist, the addition of the word “feminist” to our ideology adds nothing to our ideas. As has been explained above, it is not possible to be a Marxist without fighting for the emancipation of working women and all oppressed groups in society. One might as well call oneself “Marxist-feminist-anti-racist”, for the struggle against racism, along with the fight for women’s emancipation, also forms an integral part of the struggle for socialism. It is to the shame of some on the Left that they seem to forget this basic tenet of Marxist theory.

For this reason the addition of the word “feminist” is unnecessary and unscientific. In fact it can be counter-productive because, as illustrated above, some of the ideas of certain feminists – such as positive discrimination – actually play a role in holding back working class unity and the struggle for socialism. Introducing these conflicting ideas into Marxist theory can serve only to confuse and disorientate. While there are certainly Marxists who take particular interest in the women’s question, just as there are Marxists who take a particular interest in the environment or the national question, it would be a mistake to elevate this interest to the extent of over-exaggerating its importance relative to the rest of Marxist ideas.

Precision in language is important because that is the way in which we convey our ideas to others. If we are not clear in our language then our ideas cannot be conveyed clearly either. However, it is also vital not to attach undue weight to words and labels. People can describe their ideology however they like, but it is their actions not their words that will really define their political standpoint. This is the point of view of Marxists who understand that workers do not see the world in terms of abstract theories but in concrete action.

This stands in contrast to that strand of feminism, epitomised by the ideas of Judith Butler, that argues that “male-dominated” language is, on some level, a cause of the oppression of women. For example, when referring to an indeterminate person, many writers will use the pronoun “he”. Some feminists argue that this oppresses women and that if writers would only use a female or indeterminate pronoun more often that would go some way to ending the oppression of women.

Again, this makes the mistake of turning the problem on its head. The use of so-called “male” language is a reflection of the oppression of women in class society. Trying to remove that reflection without removing the oppression itself is futile. The result of such a pursuit is essays, books and lectures raising awareness about the need to change the way we talk, which are almost invariably read only by other, like minded academics and have no impact in popular consciousness. Rather than giving speeches on how to speak, Marxists are engaged in a practical struggle to tear oppression out of society by its roots. This is the difference between academic feminism and revolutionary socialism.

Fight against women’s oppression! Fight for socialism!

Young people, particularly at university, are often interested in exploring ideas and concepts that they may be coming across for the first time in their lives. The current crisis means that more young people than ever before are looking for ideas that challenge the status quo. This is why the ideas of Marxism are becoming increasingly popular among students at the moment. But this also goes some way to explaining the attraction of feminism to some young people.

Marxists will struggle alongside everyone who wants to fight for a better world, particularly those who are new to political ideas and activity. But Marxists also take a firm approach on our attitude towards the bourgeois democratic demands of academic feminists. Ours is a class position that has nothing in common with those feminists who seek no more than equal exploitation under capitalism. We stand for the complete unity of the working class and the struggle for socialism. This is the only way prejudices can be broken down and the material foundation for a genuinely classless and equal society can be built.