A recently joined member of the Labour Party reports on the London Young Labour 2013 conference that took place on the first weekend of December. Frequently during the weekend, guest speakers addressed the attendees as ‘the future of Britain’, which put to the test the political level of the conference. However, leading London Young Labour members mainly used the day to run a series of caucuses and workshops, which gave little room for discussing wider political questions.

As a recently joined member of the Labour Party, the London Young Labour conference 2013 I attended on the first weekend of this December was my first exposure to the internal politics of the Party. Frequently during the weekend, guest speakers addressed the attendees as ‘the future of Britain’, which put to the test the political level of the conference. However, leading London Young Labour members mainly used the day to run a series of caucuses and workshops, which gave little room for discussing wider political questions.

The weekend began well with a keynote address from Unite General Secretary Len McCluskey. He made a good opening speech in which he linked the government’s policy of austerity to the biggest crisis in the history of capitalism, and he stressed the need to raise the demands of ordinary working people, challenging young people to do so with leaders including himself, and quoting Marx fresh from the top of the Socialist Appeal paper he had just read.

Then came the questions, and, clearly fearing criticism over Unite’s handling of the Grangemouth dispute, McCluskey chose to nip the topic in the bud with a pre-emptive defence. When asked what the Labour Party could do to appeal to the rising tendency of militancy and activism in Britain, he referred to the Socialist Appeal article on “The Lessons of Grangemouth” as ‘not living in the real world, when they say what we should have done’. This statement came in direct contradiction to what he had said in his lead-off speech about the past success of industrial action and its necessity in the lives of working people under capitalism:

“They accuse me of wanting to take Britain back to the 1970s [with widespread industrial action], and they’re right, I do. Because the Tories are trying to take Britain back to the 1870s.”

Immediately after the failure of Grangemouth McCluskey claimed that the behaviour of the bosses was “not the way industrial relations should be conducted in the 21st Century.” But Grangemouth owner Jim Radcliffe’s brutal offensive against hist workers is exactly the way bosses are supposed to conduct industrial relations in the 21st Century. They are capitalists in the midst of crisis of Capitalism, who have no choice but to defend their own interests – the interests of profits.

McCluskey, on the other hand, is a trade union leader, elected to defend the interests of the working class in the face of extreme pressure from the capitalists. In the case of Grangemouth, the part Jim Radcliffe played was to be expected. But it was the choice of McCluskey and the leaders of Unite to back down on their initial call for workers to refuse the contracts offered, and not to bring the workers of other refineries and tanker drivers into the dispute or to call for a factory occupation.

I pointed out to McCluskey that it was this lack of action on the part of Unite, the failure to offer precisely the alternative he had talked about in his leading address, which had made Grangemouth an unnecessary defeat. As the final question of the Q&A session, I asked: was this the way he intended to lead the trade unions struggles which would unfold over the coming year? The response was naturally defensive, but McCluskey was again forced to contradict himself by insisting on the hesitance of the Grangemouth workers and the need to be ‘realistic’.

A ‘Young People in Politics’ panel followed Len McCluskey, which was largely a platform to talk about careers in politics with no actual political discussion itself, though it was good to hear both panellists and attendees mention the importance of ideas and policy.

The conference began to hot up with the motions, a newly introduced part of the conference, where members can mandate the London Young Labour committee. There were some good, progressive motions, on saving ULU, the Bedroom Tax and getting London Young Labour into schools. However, the majority of motions were concerned with affiliating with a reformist single-issue charity or campaign.

Many motions tried to tackle the question of various forms of discrimination. However, no explanation was given as to the root cause of these discriminations. Because of this lack of a clear explanation, several of the motions were chaotically debated and the session left people with more questions than answers, since historical explanations of the motions being put forward, as well as links drawn to the wider struggle, were much needed.

Saturday ended with a talk from Paris Lees, an influential trans journalist and LGBT activist. She gave a good speech, attempting to put her own account within a general political perspective, discussing the NHS cuts and the need to fight austerity. It seemed as if she was almost apologetic that every time she was asked to speak at an event it was to discuss her own experience; Lees therefore stressed the necessity of anti-discrimination movements, such as those by LGBT activists, to join forces with the larger body of the oppressed working class.

The next day saw prospective parliamentary candidate and Camden Councillor Tulip Siddiq and Sadiq Khan MP give keynote speeches, both in criticism of Tory policies and discussing particular issues within London Boroughs (as well as how to become a politician). I asked Siddiq about the possibility of fighting the implementation of the cuts, as exemplified by the Hull councillors. Siddiq’s response was that she would rather do carry out the cuts herself, with the compassion and care of a Labour politician, than leave it to unelected officials to carry out the same task. The difference this would make to people in her ward was left unclear.

I was approached by a number of people in the post-session break who wanted to know how it would be possible to resist the cuts within the current legal parameters – i.e. how to fight the cuts in practice, which would involve having to mobilise the entire labour movement to prevent any state officials from being able to implement the cuts. Ultimately it would require a socialist programme, and many who I spoke to were open to the suggestion of implementing socialist policies, such as nationalisation.

Later in the day saw a debate on the future of London, in which two prospective Mayor of London candidates, Diane Abbott MP and David Lammy MP, talked about what needed to be done with the city. They both favoured rent control, which, as someone later pointed out, Angela Merkel ran on during the last German general election, while Lammy wanted abolish Job Centres. However, their general concern about growing inequality in the city and gentrification in the centre – as poor people are getting pushed further and further out (Abbott even suggested centralised planning to make sure people live close to where they work) – produced some left-sounding rhetoric and suggestions from both candidates.

The final guest speakers at the conference were Labour’s four London MEP candidates. One of them, Lucy Anderson, mentioned the astronomical youth unemployment figures of countries around Europe, and suggested that London was going that way, with the figure of young people unemployed in the city 25% and rising. The obvious question is: how are Labour going to manage to scrap benefits for under-25s in favour of guaranteed youth employment within the constraints of massive austerity attacks caused by the breakdown of capitalism.

The weekend’s plenary talks had been interspersed with four caucuses, for disabled members, LGBT, women and Black and Minority Ethnics (BAME). Each caucus was exclusive to the oppressed group it concerned, while the rest of us were given talks by someone sacrificing their place in the caucuses to tell us about different forms of oppression.

Excluding people from discussions on prejudice struck me and many others as hypocritical and contradictory. Moreover, it fails to educate and involve much-needed sympathisers with these causes in the struggle against all forms of oppression. The class question – i.e. the use of different forms of oppressions being used by the capitalists to divide the working class – was never raised.

The under-19s caucus was an interesting opportunity to engage the youngest members of the conference, who may have felt intimidated by the main event but were hungry for political ideas. Instead, the organisers rushed through the caucus, having to focus on organisational matters and voting for a representative.

Overall, the weekend played out as a somewhat divisive event which seemed to have been equally strange for other first-time attendees. The reason that the event would have puzzled first-timers is that they had come to the London Young Labour looking for radical change, and in search of the ideas on which to base this change.

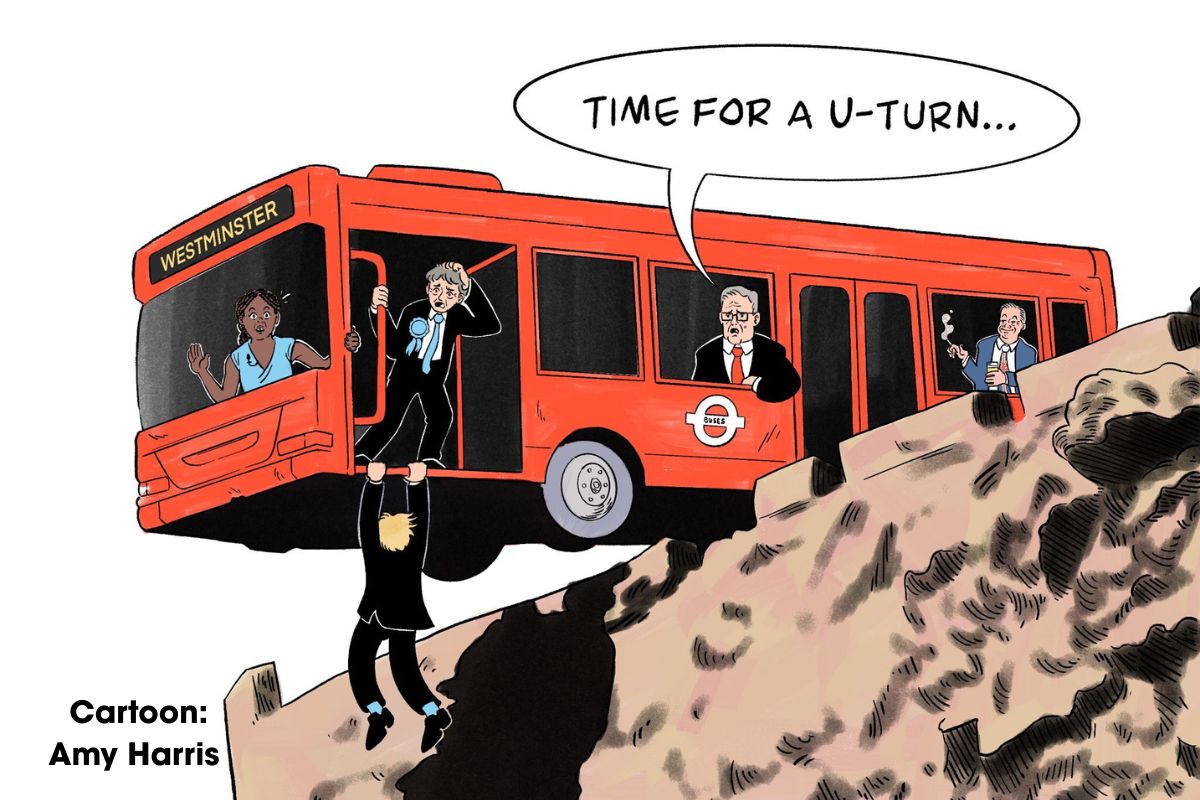

The Labour Party has shown hints of a left turn recently, but instead of such signs attaining a radical character among the youth section of the party, radicalisation has been put to the side in favour of various caucuses. It is now the task of Young Labour nationally to link oppressions, inequalities and injustices in society to a genuine fight for equality through the labour movement on the basis of a socialist programme calling for nationalisation and workers’ democracy. If this programme is advocated with the confidence that it merits, more young people will be drawn to the Labour Party as a real alternative.