The recent formation of The Independent Group (TIG) has dragged up bitter memories of the last such ‘realignment of British politics’: the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in the early 1980s. But what actually happened?

The prospect of a right-wing split away from Labour was first raised in 1979 by the former Labour home secretary Roy Jenkins, by then a pampered Eurocrat. Jenkins openly speculated about a ‘realignment’ of politics in Britain as Labour moved to the left. From then on the plotting was well underway.

It was hoped that this break by the Labour right would be accompanied by a splitting off of the one-nation Tories in the Thatcher and Tebbit led Conservative Party, forming the basis for a new ‘centre’ party.

Many of those intending to split hung on, however, in order to stop Tony Benn being elected deputy leader in 1981. Once this aim had been achieved, at the January 1981 special conference, there was nothing left to hold them back. This was particularly the case for those whose career prospects seemed grim in the face of the radicalisation taking place inside Labour.

Gang of Four

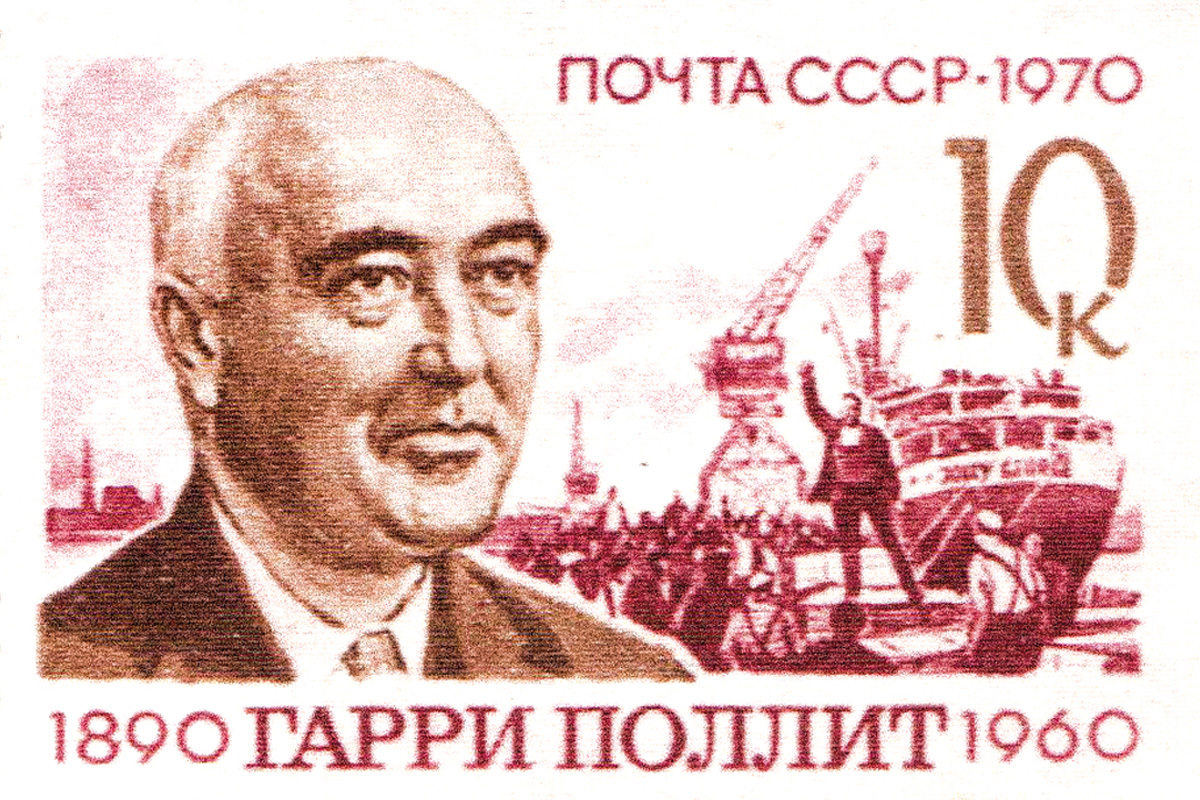

On 26 March 1981, blaming the shift to the left inside the party, four leading Labour figures – Roy Jenkins, Shirley Williams, David Owen and Bill Rodgers – announced the formation of the Council for Social Democracy in their Limehouse Declaration. This would in time become the SDP. Jenkins and co., meanwhile, became known as the “Gang of Four”.

Twenty-eight Labour MPs ended up splitting away and joining the new party – nearly all from the extreme right of the Labour Party. Many were already in conflict with their local CLPs. One lone Tory MP also joined.

The press was quick to praise them as proponents of a “new politics”. Yet it was all just rehashed Toryism – a defence of capitalism. Just like TIG today, in fact.

The Liberals soon established a ‘relationship’ with the SDP. First they created an informal agreement, and then a formal one to fight elections as a combined force.

As a result, the Alliance fought the 1983 general election riding high in the polls. Liberal leader David Steel went so far as to assert that they were “preparing for government.”

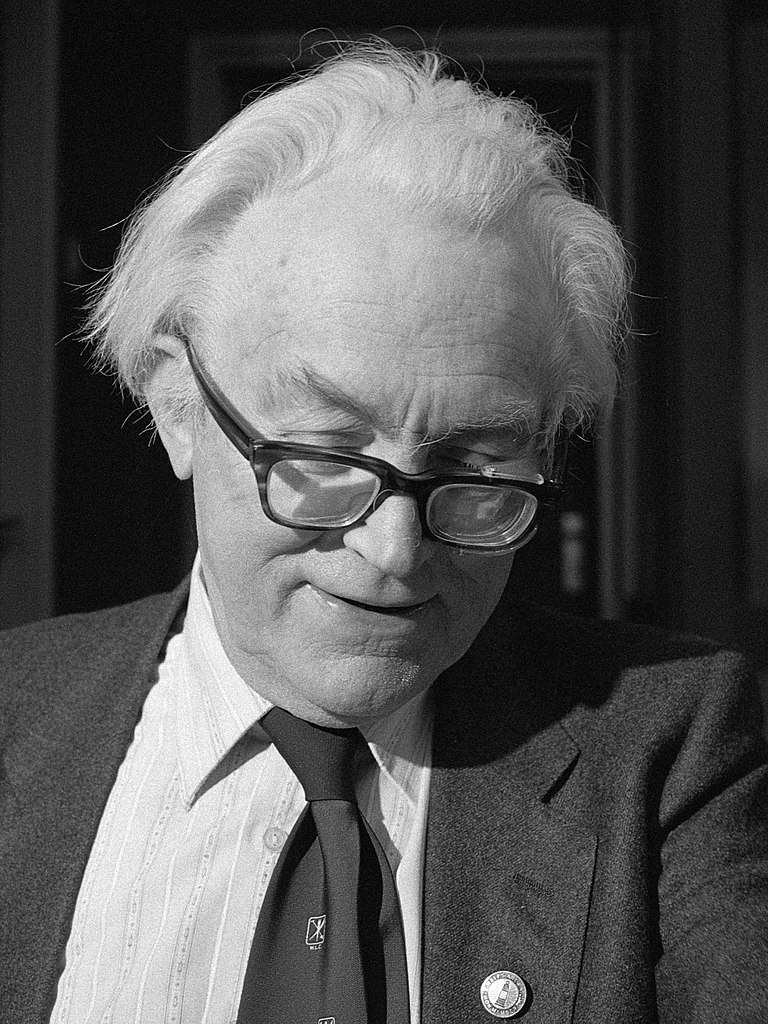

The Labour leader, Michael Foot, a dedicated socialist, came under huge pressure from the forces of the establishment both within the party and from outside. Instead of standing up to these, Foot buckled on key issues. This included the proscription of the Militant in 1982 and a failure to support Peter Tatchell, the Labour candidate in the Bermondsey by-election. Labour lost this in the face of a vicious homophobic campaign headed by the eventual winners, the Liberals.

In the face of a forthcoming general election, Foot was desperate for unity against the Tories and a prime minister who had milked the Falklands War for all it was worth. But despite his pandering to the Labour right, his critics still stabbed him in the back.

Myths and manifestos

Two myths exist about the 1983 election and the Tory ‘landslide’ victory.

Two myths exist about the 1983 election and the Tory ‘landslide’ victory.

The first is that Labour’s defeat was all the fault of the SDP splitting the vote. In fact, the SDP took votes from both Labour and the Tories. Indeed, polling analysis from the British Election Study group suggests that had the SDP never existed (and the Liberal vote remained the same as in 1979), then Labour’s vote would have risen to 33.7% (as against the actual 28%). In this case, the Tories would have got 49.5%, resulting in an even bigger majority of 180 seats.

The second myth is that the Labour collapse was all the fault of the party manifesto and its policies, which Gerald Kaufman famously described as “the longest suicide note in history”. In reality, Labour’s election programme was never as left-wing as historians describe it.

Labour’s main failing was that – in a period where counter-reforms were starting to replace reforms – the leadership never addressed the question of how the party’s policies were going to be paid for.

This would have required Labour to call for the taking over of the commanding heights of the economy, nationalising the banks and major monopolies as part of a socialist plan of production. But this was never demanded or explained. The fundamental issue of who runs society was never raised by the Labour Party.

Not only was the manifesto poorly presented but, in the words of Labour insider Lewis Minkin, “…there was always going to be a problem of leaders failing to forcefully advocate policies of which they vehemently disapproved.” (The Blair Supremacy, 2014)

Apart from Foot and a few others, the rest of the shadow cabinet made it clear that the programme Labour was fighting on was wrong and would not be implemented should they win the election. The Tories seized on this.

Labour’s campaign was also poorly organised, perhaps deliberately so, with one mistake after another. At one point, Foot and deputy leader Healey presented contradictory policies on defence, for example, as if nobody would notice. No wonder Labour was seen by voters as being divided.

It was clear that the aim of the Labour right was to turn Foot and the manifesto into scapegoats for the inevitable defeat.

Lessons for today

In this respect, a comparison between the 1983 and 2017 elections is very apt. Last year, Labour again presented a left-wing manifesto in the face of – if anything – even worse polling predictions than that faced by Foot in 1983. However, Corbyn put his weight behind it and, as a result, the electorate saw him as a leader who would actually implement this popular programme.

In this respect, a comparison between the 1983 and 2017 elections is very apt. Last year, Labour again presented a left-wing manifesto in the face of – if anything – even worse polling predictions than that faced by Foot in 1983. However, Corbyn put his weight behind it and, as a result, the electorate saw him as a leader who would actually implement this popular programme.

Labour began to attract votes, especially from the young people. After years of austerity and a disheartening lack of choice in election after election, workers and youth saw a glimmer of hope once again. Attempts by the Blairites to undermine the campaign gained little traction and were lost amidst the Corbyn surge.

This is a critical lesson in how to fight any SDP clone today. The lessons of 1983 must be learnt: compromise and accommodation with those opposed to socialism will not work. Instead, such weakness simply invites aggression. Concessions will only lead to further attacks and demands from Labour’s ‘grandees’ for a retreat back to the old failed politics of Blair and Kinnock.

The Independent Group and their friends who remain in the PLP are firmly wedded to capitalism, austerity, imperialist war, and attacks on workers’ rights. Far from undermining support for Labour, booting these types out of the party would actually increase its popularity. Workers would see Labour as a party that is actually willing and determined to carry out socialist policies – provided that such policies are put forward boldly.

Ironically, the SDP was not rewarded for their treachery. In the 1983 election, only six SDP candidates were voted into the new parliament. Most sitting SDP MPs were defeated.

The dregs of the SDP were swallowed up five years later by the Liberals. Their only surviving marker was in the name change to the Liberal Democrats. Those careerists who could not progress using the vehicle of the Lib Dems returned to Labour, invited back under Blair to boost the forces of big business inside the party.

It is time to put the final nail in the SDP coffin. We should bury The Independent Group and the Blairites – and fight for a socialist Labour government.