Following the election of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader, civil war has broken out within the Party over who should control it. The right wing, with the full support of the ruling class, is hell-bent on discrediting and ousting Corbyn and re-establishing their control. Hundreds of thousands of Corbyn supporters have now joined the Party, while some Blairites are leaving in disgust. This struggle represents a fight to the death.

Lord Mandelson, one of the architects of New Labour, has openly admitted the existence – in reality – of two Labour parties. Right-wing Labour MP Frank Field proposed that the Party have two leaders, one in Parliament and the other outside, thereby removing Corbyn. In such circumstances, a split is inevitable.

The ruling class is following this process very closely. Lord Owen, a former Labour foreign secretary, has even suggested a timeline for a split: “For at least two years, fight like hell, I would say. I wouldn’t contemplate a new party until the end of 2017,” he said. Lady Shirley Williams supported him saying, “eventually there will be a new party of the centre left”.

Such plans to split the Labour Party are not new. The ruling class has encouraged this whenever there has been a danger of the Right losing control of the Labour Party.

It happened in 1931 with the formation of the National Government, and again in 1981 with the formation of the SDP. Such splits were used to undermine the Labour Party and prepare the way for a National or Tory government. Of course, there are many differences between now and then, but the logic of the situation is pushing in the same direction.

The main difference between then and now is that the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) is even more dominated by right-wing careerists. After years under leaders like Kinnock and Blair, the top of the Party has become increasingly rotten, having wholeheartedly embraced the market and the logic of capitalism.

Whereas in 1931 (and in 1981 for that matter) the split was a relatively minor affair in terms of the numbers of Labour MPs involved, a future split would see a large proportion of the PLP cross the floor.

A great betrayal

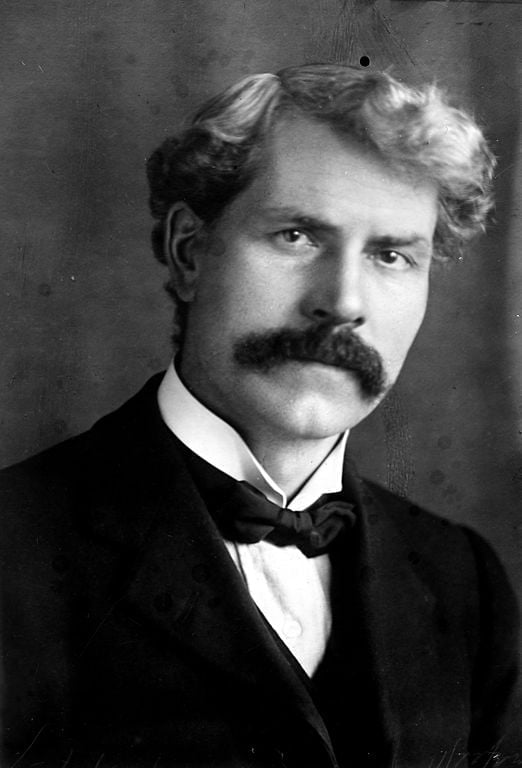

The split in 1931 constitutes one of the greatest betrayals in Labour history, when Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister, deserted to the Tories and Liberals to form a National Government. He stood for the “national interest” – the national interest of course being the interests of big business. He, and the few other Labour MPs who split to form the National Government, had the full backing of the ruling class.

“Mr Snowden [a Labour minister in the National Government], with rare though belated courage, has shown that he at least knows where that duty lies, and, whatever the attitude of the rest of his Party, the public will never grudge him any assistance which he may need in carrying through his difficult task,” thundered the august London Times in early 1931.

Then as now, capitalism was experiencing a deep world slump of over-production. In 1929, just over one million were unemployed, but by 1931 this number had risen to 2,700,000 – 22% of the insured workers. Production had declined to 8% below that of 1913 levels. The growing budget deficit threatened to force Britain off the gold standard. The government was informed that loans could be secured from the bankers, but only with massive cuts in public spending.

The government-sponsored May Committee recommended that “economies” amounting to £96.5 million should be made, the majority of which should be cuts to unemployment benefits. Labour ministers MacDonald, Snowden, Henderson, Thomas and Graham instead proposed cuts of some £56 million, which the majority of the Cabinet accepted.

The TUC registered its firm opposition to the cuts, which MacDonald regarded as overlooking “dreadful realities”. This opposition forced MacDonald’s hand.

National interest?

King George V was very much part of the plot to form the National Government. MacDonald and the leaders of the opposition parties were in constant touch with the Palace, which acted as broker. “In a strictly constitutional capacity he [the King] has rendered a signal service to his people”, noted The Times.

King George V was very much part of the plot to form the National Government. MacDonald and the leaders of the opposition parties were in constant touch with the Palace, which acted as broker. “In a strictly constitutional capacity he [the King] has rendered a signal service to his people”, noted The Times.

In the future, the monarchy could be similarly used again. Prince Charles, the current heir to the throne, is already deeply involved politically in pressuring ministers over various hobbyhorses behind the scenes.

In 1931, the King met both Baldwin, the Tory leader, and Sir Herbert Samuel, the Liberal leader, to discuss the “national interest”. Sir Herbert cynically informed the King: “in view of the fact that the necessary economies would prove most unpalatable to the working classes, it would be to the general interest if they could be imposed by a Labour government.” If that failed, a National Government headed by MacDonald would be the next best option.

After the formation of the National Government, Snowden told MacDonald that “tomorrow every Duchess in London will be wanting to kiss me”. The ruling class were likewise delighted with the outcome. “All concerned are to be warmly congratulated on this result,” commented The Times.

MacDonald’s former colleagues were stunned by the speed of events. They had all seen the need for sacrifices and a balanced budget, but had been kept in the dark, stated Henderson. When the split came, right-wingers Henderson and Clynes did not follow MacDonald but remained inside the Labour Party to prevent it falling into the “wrong” hands.

While the Labour leaders wept over the “great loss to the Labour Movement”, the rank and file forced the National Executive to expel MacDonald and the other traitors from the Party.

Move to the Left

The betrayal pushed the ranks of the Labour movement far to the left. Even the surviving Labour leadership was pushed to the left – in words at least.

“The revulsion from MacDonaldism caused the Party to lean rather too far towards a catastrophic view”, warned Clemet Attlee. “The attitude of the rank and file of the Party seems to me to be extremely dangerous at the moment,” wrote Stafford Cripps. “There is a strong tendency to discard the realities of the situation.” The Independent Labour Party swung politically between reformism and revolution. The 1932 Labour Conference, cleansed of MacDonald and co., saw a dramatic radicalisation, proclaiming that “the main objective of the Labour Party is the establishment of socialism.”

Today, with a deepening crisis of capitalism, the capitalists cannot tolerate a left-leaning Labour government. They are therefore conspiring to split the Labour Party prior to the election.

While this would damage Labour electorally, it will, as in 1931, sharply push the Labour Party to the left. This would serve to politically cleanse the Party. Faced with a new National Government or coalition carrying out vicious austerity, a left-moving, anti-austerity Labour Party would rapidly pick up support. While the ruling class fears this, it has little room for manoeuvre.

In the words of Beatrice Webb in 1931, “On the whole I rejoice in the crisis as I think it will clear the issue and purify the Party.”

For the advanced sections of the working class and the youth, such an event will even more sharply pose the need to overthrow capitalism. As in 1931, the ideas of Marxism will become extremely attractive.