For Marxists, the question of what programme we defend and the slogans we raise is a question that relates directly to the concrete tasks that confront the working class at each stage in its struggle: from the most basic economic strike or an election, up to the task of organising an insurrection.

In revolutions – such as that of Russia in 1917 – consciousness changes so quickly and the struggle takes such sharp turns, that what were the most advanced slogans and programme of yesterday may become the most conservative brake on action if repeated tomorrow. As such, each sharp turn tends to produce crises in the revolutionary party as it is forced to constantly reassess its own slogans and methods.

A new perspective

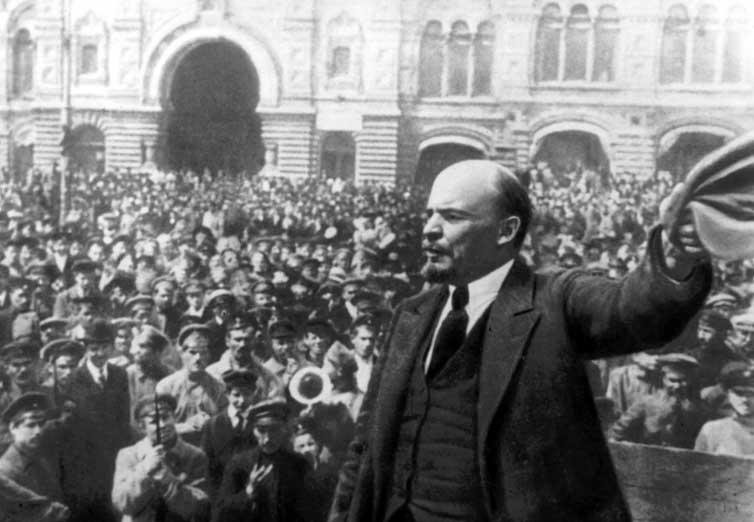

In April 1917, the return of Lenin to Russia caused just such a crisis among the Bolsheviks. The outbreak of revolution in February had made the old slogans of the Party practically obsolete. The Old Bolsheviks, who were first to arrive in Petrograd after February (Stalin and Kamenev), were theoretically unprepared for such a sharp turn. Repeating the old slogans, they found themselves in a position of rapprochement with the Mensheviks and supporting the continuation of the war.

Lenin’s return opened up a period of crisis and political rearmament among the Bolsheviks, with a new perspective: the seizure of power by the working class through the soviets.

In September 1917, following the collapse of Kornilov’s coup, the decisive turn of the working class towards the Bolsheviks placed a new task before the party: that of immediately preparing for an insurrection and leading the working class to power. Once more the party entered into crisis. In the words of Trotsky:

“It might seem as though the April Days had returned – Lenin again in opposition to the Central Committee. The questions stand differently, but the general spirit of his opposition is the same: the Central Committee is too passive, too responsive to social opinion among the intellectual circles, too compromist in its attitude to the Compromisers. And above all, too indifferent, fatalistic, not attacking à la Bolshevik the problem of the armed insurrection.”

Lenin’s absence

However, Lenin could not conduct his struggle as he had back in April, openly at party conferences. He was a wanted man, still in hiding since the outbreak of the July events. And his absence was felt in the Bolshevik Central Committee.

In July, the workers of Petrograd were with the Bolsheviks. In the provinces and the countryside however, the great mass of the downtrodden and oppressed were only dimly aware of “Bolshevism” and its slogans. They were not politically prepared to support an insurrection.

By September however, things had changed decisively. In a series of blistering letters to the Bolshevik Central Committee, Lenin underlined this fact and posed point-blank the new task: immediate preparation for an insurrection. His starting point was the international conjuncture: revolts and repression across the belligerent nations of Europe showed that a favourable, European-wide revolutionary period was opening. The Kornilov affair on the one hand and the conspiracies of the ruling class to surrender Petrograd to the iron heel of the German fleet on the other had revealed to all who the real defenders of the revolution were.

The peasant war

Perhaps most important of all, the class struggle in the countryside was taking on gigantic dimensions. Fed up of waiting for the Provisional Government to act on its promises of land to the peasantry, the rural poor had taken matters into their own hands. All of this Lenin gauged from his position in hiding, from the slightest of hints in the press, and through individual discussions.

On September 14, the so-called Democratic Conference, representing a variety of organisations including soviets, unions, peasant and business organisations, was convened by the Mensheviks and SRs. Through the Democratic Conference and the Pre-Parliament which it elected, the petty bourgeois leaders sought on the one hand a cloak of democratic legitimacy, and on the other were seeking to get the revolution caught up in the web of a pointless and drawn out parliamentary talking shop.

Lenin gave little weight to the body’s parliamentary arithmetic or the eloquence of its speakers. He did however place great import on the fact that the peasant representatives consistently voted against the bourgeois Kadet Party. This was one more sign that the peasant masses were no longer willing to follow the bourgeois parties. They were done with words; they demanded deeds. There was no time to wait: the Bolsheviks had to pass onto the offensive.

Wait for the soviet congress?

Meanwhile, one after another, the soviets, unions and factory committees – the organisations closest to the proletariat – had responded to the Bolshevik’s slogans and elected Bolshevik majorities. Despite this fact, the Central Executive of the Soviets was still in the hands of the Mensheviks and the SRs, who were resisting calls for a new Soviet Congress, which they knew the Bolsheviks would dominate. By the end of the Democratic Conference the old Executive were forced to submit to pressure to name a date for a new Soviet Congress; the Congress would take place in five weeks – an eternity in conditions of revolutionary upheaval.

Meanwhile, one after another, the soviets, unions and factory committees – the organisations closest to the proletariat – had responded to the Bolshevik’s slogans and elected Bolshevik majorities. Despite this fact, the Central Executive of the Soviets was still in the hands of the Mensheviks and the SRs, who were resisting calls for a new Soviet Congress, which they knew the Bolsheviks would dominate. By the end of the Democratic Conference the old Executive were forced to submit to pressure to name a date for a new Soviet Congress; the Congress would take place in five weeks – an eternity in conditions of revolutionary upheaval.

Lenin knew the Old Bolshevik party leaders well: more distant from the factories and in daily contact with the intellectuals of the Menshevik and SR parties, they were prone – in the absence of Lenin – to be infected by the mood of the intellectuals and fall into passivity.

In waiting for the Congress, Lenin saw the greatest danger to the revolution. He outlined the changed conditions in a letter to the Central Committee, urging the Bolshevik leadership to immediately begin the preparations for an insurrection. Those who placed illusions in the old Executive Committee or were for participation in the Pre-Parliament, Lenin denounced as “miserable traitors” and “blacklegs”.

Lenin went further: “I am compelled to tender my resignation from the Central Committee, which I hereby do, reserving for myself freedom to campaign among the rank and file of the Party and at the Party Congress. For it is my profound conviction that if we “wait” for the Congress of Soviets and let the present moment pass, we shall ruin the revolution.” (The Crisis Has Matured, Lenin 29 Sept 1917)

In the end, nothing came of this threat. However, the party’s Central Committee were shocked by the sudden change to an offensive footing. Against the prevarications of the party leaders, Lenin sought to bring to bear the weight of the party ranks.

Already in July, Lenin had posed the question of the Bolsheviks seizing power in the name of the Factory Committees if the Soviets remained under the domination of the petty bourgeois democrats. In the end this would not prove necessary: the plans for the insurrection went ahead and the Bolsheviks seized power upon the opening of the Soviet Congress.

As Trotsky explained in his History of the Russian Revolution however: “What seemed untimely as a direct tactical proposal became expedient as a test of attitudes in the Central Committee, a support to the resolute against the wavering, a supplementary push to the left.”

A party of cadres, not supermen

The Bolshevik Party – the most revolutionary party in history – was not made of supermen. Its members and leaders were capable of hesitation and disorientation. The crisis reached its peak on the eve of insurrection, when Gorky’s newspaper published an article by Zinoviev and Kamenev against the armed insurrection.

The Bolshevik Party – the most revolutionary party in history – was not made of supermen. Its members and leaders were capable of hesitation and disorientation. The crisis reached its peak on the eve of insurrection, when Gorky’s newspaper published an article by Zinoviev and Kamenev against the armed insurrection.

At such a decisive moment of the revolution – a point of no return – all the potential difficulties loomed as gigantic and insurmountable obstacles before those who had been tinged with opportunism.

Others, like Stalin, adopted a passive “wait and see” attitude until after the point of the insurrection’s success.

However, the Bolshevik Party was also a party of trained Marxist cadres, capable of theoretically grappling with new ideas and tasks as they posed themselves. As such the intervention of Lenin did its job: the party was politically rearmed, and was capable of leading the working class in the greatest revolution in history.