“Out of this spark will come a flame.”

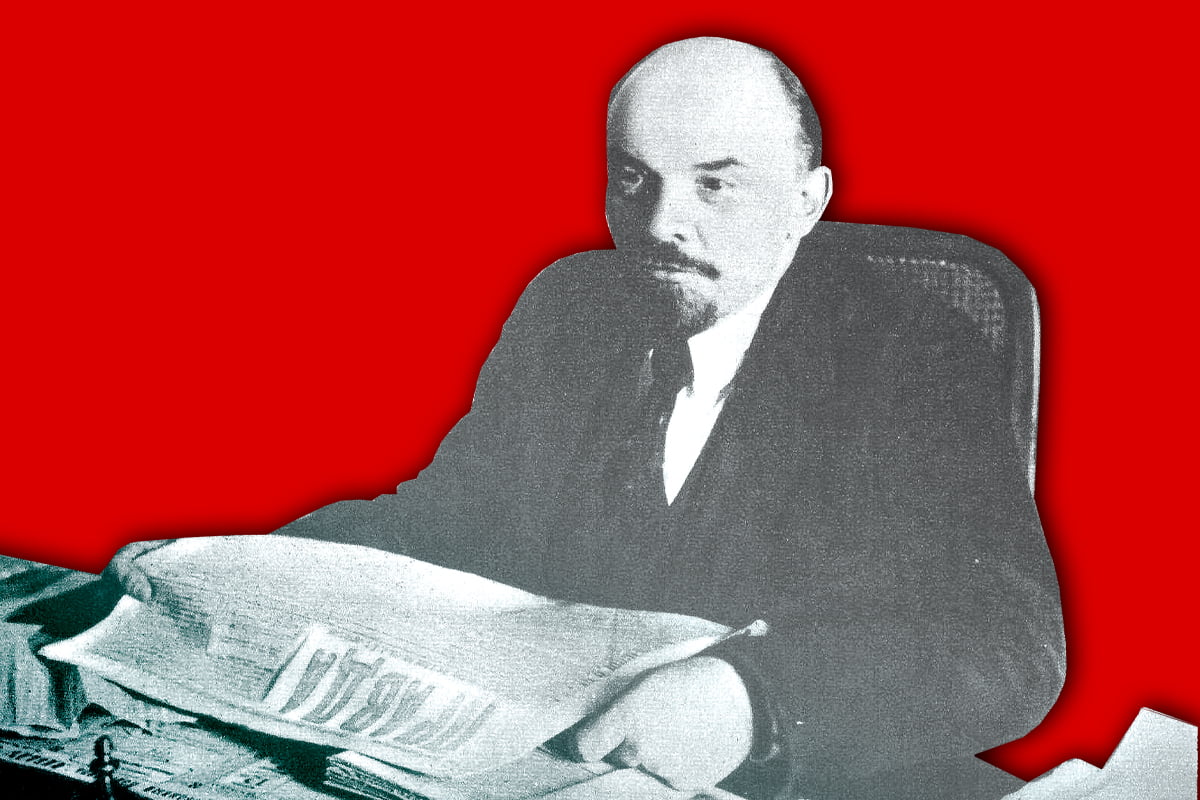

Such was the strapline of Lenin’s newspaper Iskra (‘Spark’), which he founded in 1900 with a small group of comrades. How true those words were! Only 17 years later, Lenin and the Bolsheviks led the working class of Russia to power in the world’s first successful socialist revolution.

Lenin’s success was based primarily on his profound grasp of Marxist theory. Armed with this, Lenin correctly understood the leading role that the emerging working class would play in a future Russian revolution, as well as the counter-revolutionary role of the bourgeois liberals.

Flowing from this perspective of a workers’ revolution came Lenin’s understanding of the need for an independent revolutionary party of the working class.

Lenin understood how, in the conditions of a mass movement, such a revolutionary party would have the potential to connect with and lead millions of workers and other oppressed layers to overthrow the Tsarist regime, and take power into their own hands.

How to build such a party was therefore a burning question of the movement at the turn of the 20th century.

Early years

The 1890s saw an explosion of Marxist study circles organised in the developing industrial centres of Russia. Stormy strikes were breaking out at the newly developed factories, leading to a growing awareness of the working class of itself as a class.

Various ‘Social-Democratic’ (i.e. Marxist) propaganda groups emerged in this period, which would train the initial cadres of Russian Marxists.

Lenin was active in the Petersburg Social Democrats from late 1893. It was during this time that Lenin learnt how to combine political education with the practical activity of organising workers in struggle.

Agitational leaflets were used with great success to connect with workers in the factories, particularly those on strike.

Revolutionaries would discuss with the workers their grievances, and take note of their demands. They would then produce leaflets that exposed the particular struggle in agitational form, and appeal to other workers for solidarity. These leaflets proved to be immensely popular.

The local limitations of this approach were soon felt, however. Whilst such leaflets had an effect, what was needed was literature that could generalise these experiences across the whole of the class struggle, and bring the most advanced ideas and methods to the forefront.

View this post on Instagram

Professionalisation

Therefore in the winter of 1895, representatives from Social-Democratic groups from across Russia met to discuss how to professionalise this work. They agreed to establish a popular literature for workers that could generalise their experiences, whilst connecting them with Marxist theory.

In order to limit the potential for arrests, this literature would be produced abroad. Lenin was therefore sent to negotiate with the veteran Emancipation of Labour Group, which had been in exile in Switzerland since the early 1880s.

The Group was led by Plekhanov, who was considered the leading Russian Marxist theoretician of the time. After many years of exile, however, the Group had become detached from the real workers’ movement inside Russia.

It was agreed that the Group would produce a Marxist theoretical journal, Rabotnik (‘The Worker’) from abroad, whilst a more popular paper would be published in the interior called Rabocheye Dyelo (‘The Workers’ Cause’).

Just as the first issue of Rabocheye Dyelo was being prepared for printing, however, the police carried out a large-scale raid and arrested most of its leaders – including Lenin.

View this post on Instagram

‘Economism’

With nearly all the experienced cadres of the Petersburg League of Struggle now in Tsarist jails, other – mostly inexperienced and politically raw – comrades were forced to fill their shoes.

This had a negative effect on the political development of the organisation. Given the previous success of agitational leaflets in connecting with workers in struggle, the new leadership moved heavily in this direction.

Over time, the leadership – mostly composed of students and other intellectuals – began to adapt itself more and more to the most backward layers of the working class.

The idea took hold that workers were only interested in struggling for ‘bread-and-butter’ economic demands, such as increased wages, and shorter working hours. They contemptuously believed that political demands and theory were ‘too complicated’ for workers to understand.

They thought the task of revolutionaries was therefore to simply assist workers in carrying out their economic struggles, and leave the political struggle to bourgeois liberals. This meant effectively tail-ending the movement, and abandoning the building of a revolutionary party.

This trend – which became known as ‘Economism’ – found its expression with the launch of a new paper, Rabochaya Msyl’ (Workers’ Thought) in 1897.

It was therefore necessary for the genuine Marxists to declare war on this tendency, and combat it energetically within the labour movement.

As such, it was decided to organise a founding congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), which was held in Minsk in 1898.

At this time, Lenin was serving a three-year term of exile in Siberia. Although he was unable to attend, he followed the development keenly, and contributed to the preparations.

Within a month of the congress, however, five of the nine participants had been arrested. This put an end to a national organisation, and the committees soon sank back into routine local work.

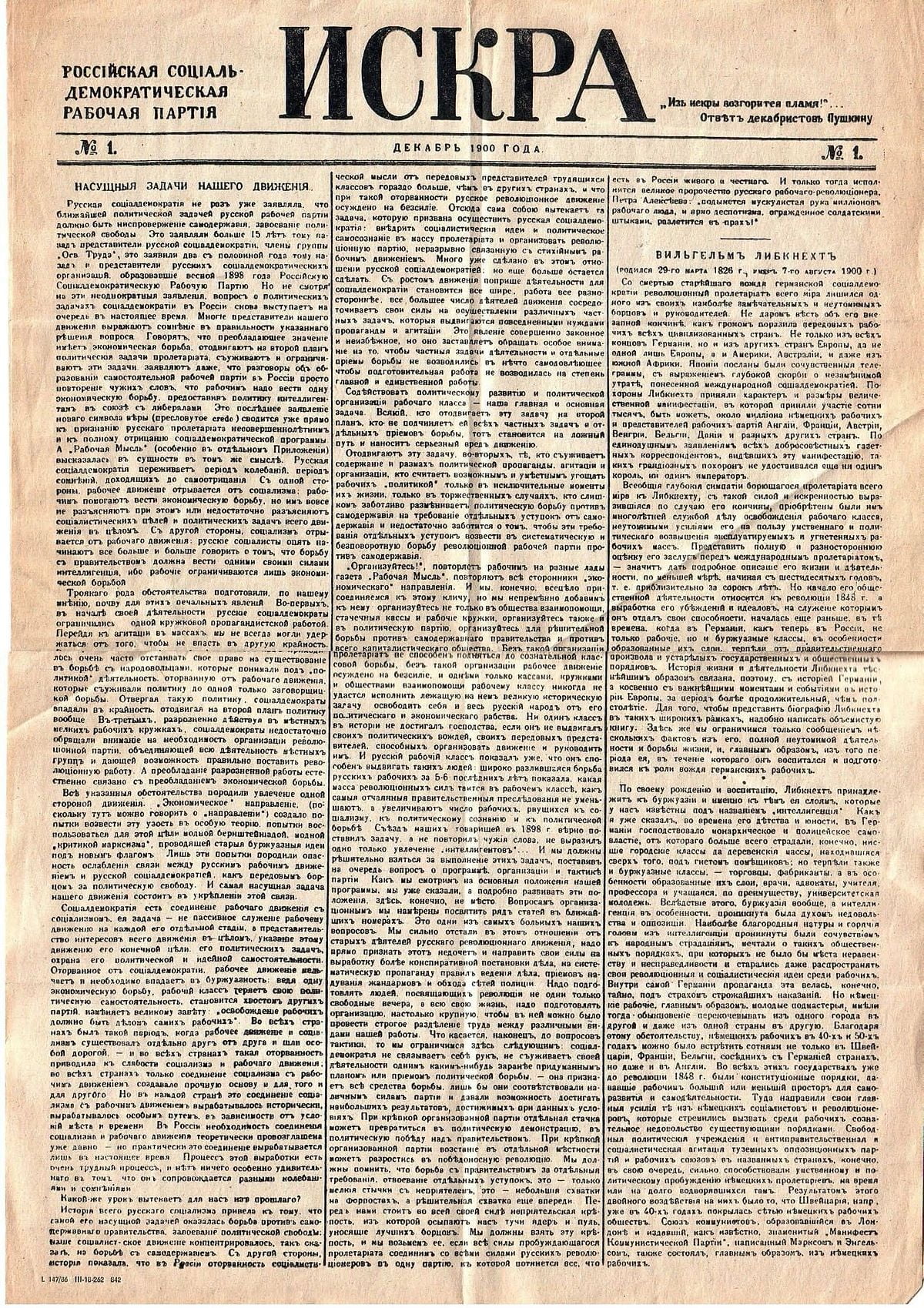

Iskra

By 1900, as Lenin was reaching the end of his period of exile, the situation for the genuine Marxists in Russia appeared bleak.

The Economists had established themselves as the dominant trend amongst the various Social-Democratic groups. What’s more, frequent arrests served to disrupt and set back the work of the various committees.

Undeterred however, Lenin began to make preparations to reestablish the RSDLP on a healthy basis. Key to his plan was the launching of a new all-Russian Marxist paper, Iskra, in alliance with Plekhanov’s Emancipation of Labour Group, to defend the ideas of Marxism.

The Declaration of the Editorial Board of Iskra, published in September 1900, reads like a declaration of war on all the reformist tendencies in the Russian labour movement, and especially the Economists.

Lenin understood that the essence of a political party or tendency is its ideas: its guiding philosophy, programme, and methods. The organisation is merely a vehicle to transmit these ideas into the wider labour movement.

Hence the Declaration put the question of political clarification front and centre of the campaign to refound the party:

“To establish and consolidate the party means to establish and consolidate unity among all Russian Social-Democrats…Such unity cannot be decreed, it cannot be brought about by a decision, say, of a meeting of representatives; it must be worked for.

“In the first place, it is necessary to work for solid ideological unity which should eliminate discordance and confusion that – let us be frank! – reign among Russian Social Democrats at the present time. This ideological unity must be consolidated by a party programme.”

Instead of simply calling all the different trends in the movement to come together under one umbrella, Lenin argued that the only real basis for a united revolutionary party was agreement on its core ideas and principles.

As Lenin later explained in What is to be Done: “Without revolutionary theory there can be no revolutionary movement.”

An example of Lenin’s approach is found in his famous article Where to Begin, which was published in the fourth issue of Iskra. In it, Lenin laid bare the results of the Economists’ ideas in practice: the state of fragmentation of the revolutionary forces; their absorption into purely local work; and their amateur conduct that resulted from this.

To combat this, Lenin argued for the need for a political newspaper. This would link up the various struggles of workers across Russia, generalise their experiences, and raise class consciousness to the understanding of the need for an all-out struggle against the Tsarist regime.

Collective organiser

Lenin was of course not the first revolutionary to utilise pamphlets and newspapers for propaganda and agitation. The effectiveness of this has been recognised by revolutionaries ever since the invention of the printing press.

What Lenin grasped perhaps more keenly than others was the potential for a revolutionary paper to act as a collective organiser.

In the Declaration of the Editorial Board of Iskra, Lenin explained:

“We will exert our efforts to bring every Russian comrade to regard our publication as his own, to which all groups would communicate every kind of information concerning the movement, in which they would relate their experiences, express their views, indicate their needs for political literature, and voice their opinions concerning Social-Democratic editions: in a word, they would thereby share whatever contribution they make to the movement and whatever they draw from it.”

This theme was developed in Where to Begin, where he argued:

“With the aid of the newspaper, and through it, a permanent organisation will naturally take shape that will engage, not only in local activities, but in regular general work, and will train its members to follow political events carefully, appraise their significance and their effect on the various strata of the population, and develop effective means for the revolutionary party to influence these events.

“The mere technical task of regularly supplying the newspaper with copy and of promoting regular distribution will necessitate a network of local agents of the united party, who will maintain constant contact with one another, know the general state of affairs, get accustomed to performing regularly their detailed functions in the All-Russian work, and test their strength in the organisation of various revolutionary actions. This network of agents will form the skeleton of precisely the kind of organisation we need…”

In contrast to the amateur methods of the Economists, Lenin argued for a party made up of professional revolutionaries: people who were prepared to commit themselves fully to building the party.

Lenin developed this argument in greater detail in his landmark book What is to be Done?.

He explained how through establishing connections with workers, and training them to become professional revolutionaries, the ‘skeleton’ of a revolutionary party would be established in every major workplace and neighbourhood. They could in turn connect with a much wider layer of advanced workers.

Workers’ paper

For the paper to play this role, it required the active participation of as many workers as possible to contribute their ideas and experiences towards it. As Lenin implored in his “Letter to a Comrade (1904)”:

“All Social-Democrats must work for the Social-Democratic paper. We ask everyone to contribute, and especially the workers.

“Give the workers the widest opportunity to write for our paper, to write about positively everything, to write as much as they possibly can about their daily lives, interests, and work.”

Receiving such contributions allowed the editorial board to generalise the experiences from local struggles, and uncover the deeper processes at work in the development of the class struggle.

By then bringing these processes to the surface in articles in the paper, and combining them with Marxist theory, it allowed workers to learn the lessons from each others’ experiences, and understand how they fit into the general perspectives for revolution.

And importantly, the paper provided a guide to action, by drawing out the most far reaching demands and slogans, necessary to raise the class struggle to a higher level.

This was in stark contrast to the approach taken by the Economists, which merely amounted to telling workers how bad their conditions were, i.e. what they already knew.

Ultimately it was on the strength of the ideas contained within the paper, and their ability to show a way forward, that workers would be inspired to make huge sacrifices of their time, money, and energy, to build the revolutionary party.

Growth

The work of establishing the authority of Iskra amongst the revolutionary workers was painstaking and slow at first. Enormous difficulties and sacrifices had to be made to print and smuggle copies of the paper into Russia.

Nadezhda Krupskaya, the secretary of Iskra, estimated that only as few as 10 percent of the printed copies ever made it across the border. Many of the smugglers were arrested in the process.

By the end of 1901, there were only nine Iskra agents in the whole of Russia. But due to their tireless efforts to establish connections with the numerous workers’ revolutionary committees, and win them politically to the ideas of Iskra, the influence of the Economists was steadily eroded.

This network of agents soon grew to about 100-150 or so professional revolutionaries. These in turn were each in contact with multiple committees, each of which organised hundreds of workers.

Such was the growth of Iskra, that by the time of the preparations for the Second Congress of the RSDLP in 1903, the Iskraites had established themselves as the leading force amongst the committees.

It was at this congress that the RSDLP first split into the ‘Bolshevik’ (majority) and ‘Menshevik’ (minority) factions. Despite Lenin’s Bolshevik faction having a majority of the congress ultimately on its side, the Mensheviks eventually ended up taking control of Iskra due to their campaign of internal sabotage, and the defection of Plekhanov to their camp.

On the surface, Lenin and the Bolsheviks emerged from the congress organisationally weaker than the Mensheviks. But politically, their ideas had been strengthened.

Revolution

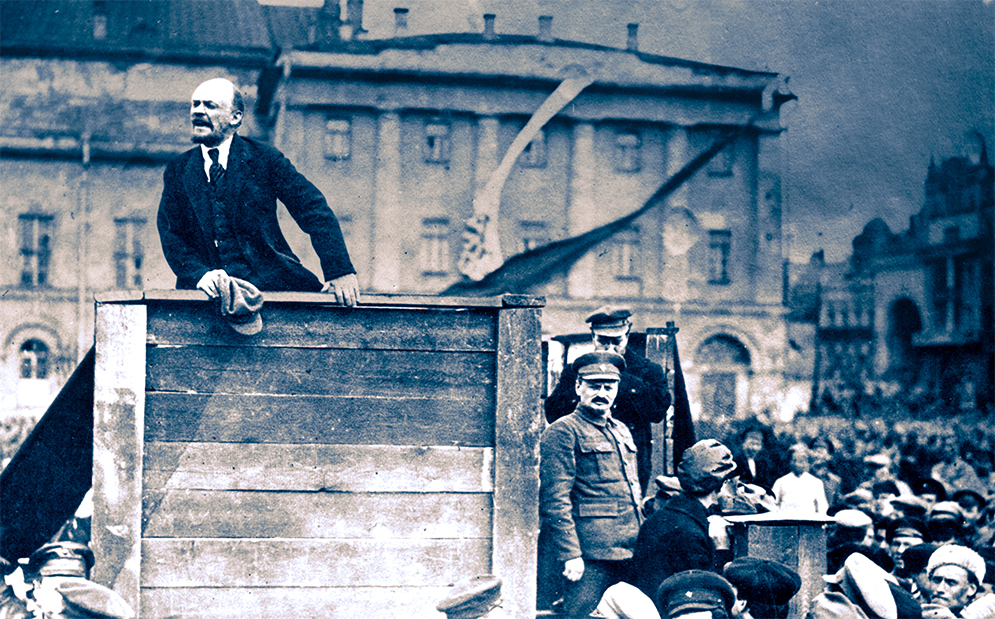

During the revolution in 1905, the fortunes of the Bolshevik faction were reversed under Lenin’s leadership. In the heat of the struggle, thousands of the most militant and class-conscious workers joined the Bolsheviks.

With the opening up of semi-legal conditions, the Bolsheviks produced a new daily paper, Novaya Zhizn’ (‘New Life’), which reached a circulation of 50,000 to 80,000. With this, they were able to reach and influence hundreds of thousands, or possibly even millions.

The preparatory work of Iskra, in establishing the initial skeleton of the party over the preceding years, was beginning to bear fruit. Lenin remarked that “in the spring of 1905 our party was a union of underground circles; by the autumn it had become the party of millions of the proletariat”.

The 1905 revolution was ultimately defeated, with the movement thrown back for a number of years.

Lenin and the Bolsheviks continued to publish various revolutionary papers during this period. Their task at this time, however, was not to reach the masses, but to preserve and train Marxist cadres in anticipation of the next outbreak of revolution.

Pravda

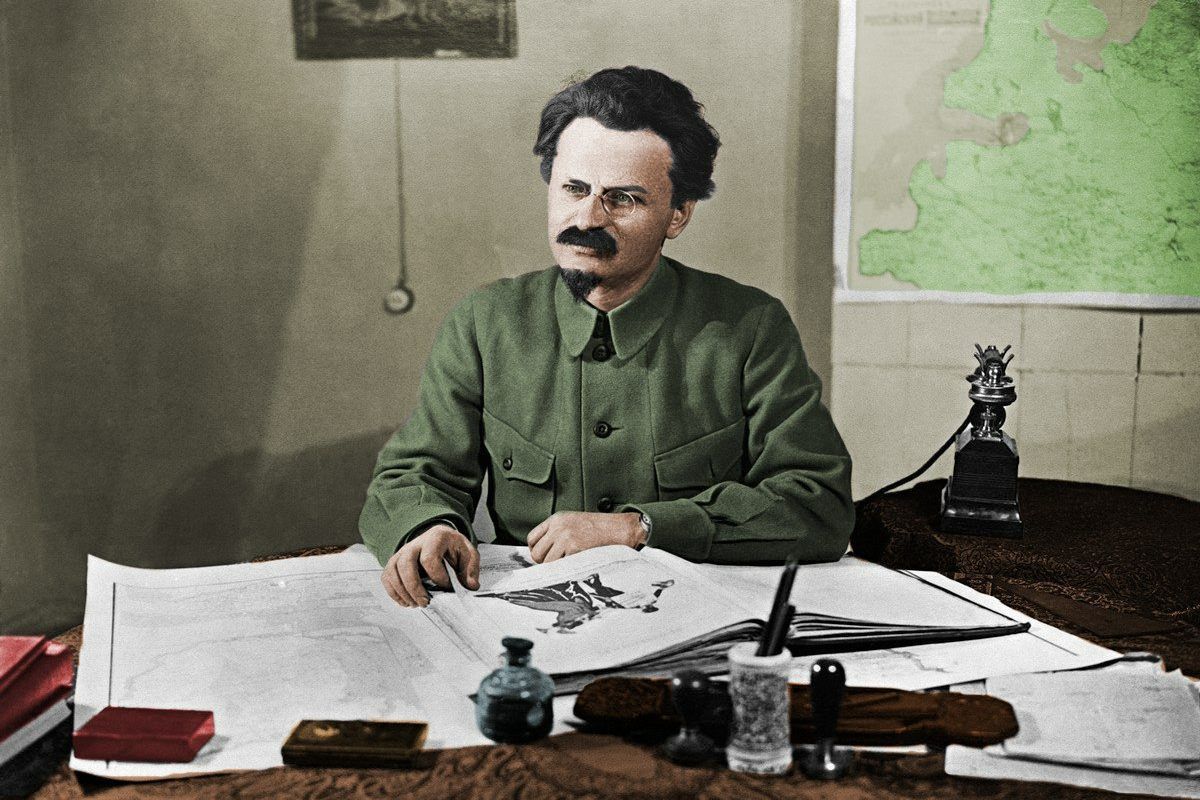

With the revival of the class struggle in 1912, the Bolsheviks, under Lenin’s initiative, were again able to produce a mass daily paper; under the name of Pravda (the ‘Truth’). It was the first legal paper, which meant it had to do battle with the censor.

Pravda functioned as a genuine collective organiser. Worker-correspondents wrote in every issue, commenting on all aspects of working class life. Over 5,000 letters were received in its first year alone.

Thousands of groups of workers were established tasked with collecting contributions to the paper, distributing it, and raising funds. By the spring of 1914, its circulation was nearly 40,000. Since many copies were often passed round the factories, however, its influence was much greater.

The outbreak of the first world war in 1914 cut across the development of the revolutionary movement. The Bolshevik Party was reduced to small handfuls of supporters in each area.

Yet with the outbreak of the February Revolution in 1917, the masses again entered the stage of history.

Although it is true that no party ‘organised’ the revolution, in every factory and neighbourhood there were of course workers that took the lead. These were in the main Bolsheviks, who had been politically trained over the previous decades, and especially during the years of Iskra and Pravda.

After the fall of the Tsar, the flood of politically raw workers and peasants into the soviets meant that the Bolsheviks were initially in a minority during the early months of the revolution.

There existed a solid core of the party, however, which had been trained in Marxist ideas and methods over the entire preparatory years. With Lenin’s leadership, this layer would rapidly connect with the most revolutionary workers, to become a mass party and the decisive factor in leading the October Revolution.

View this post on Instagram