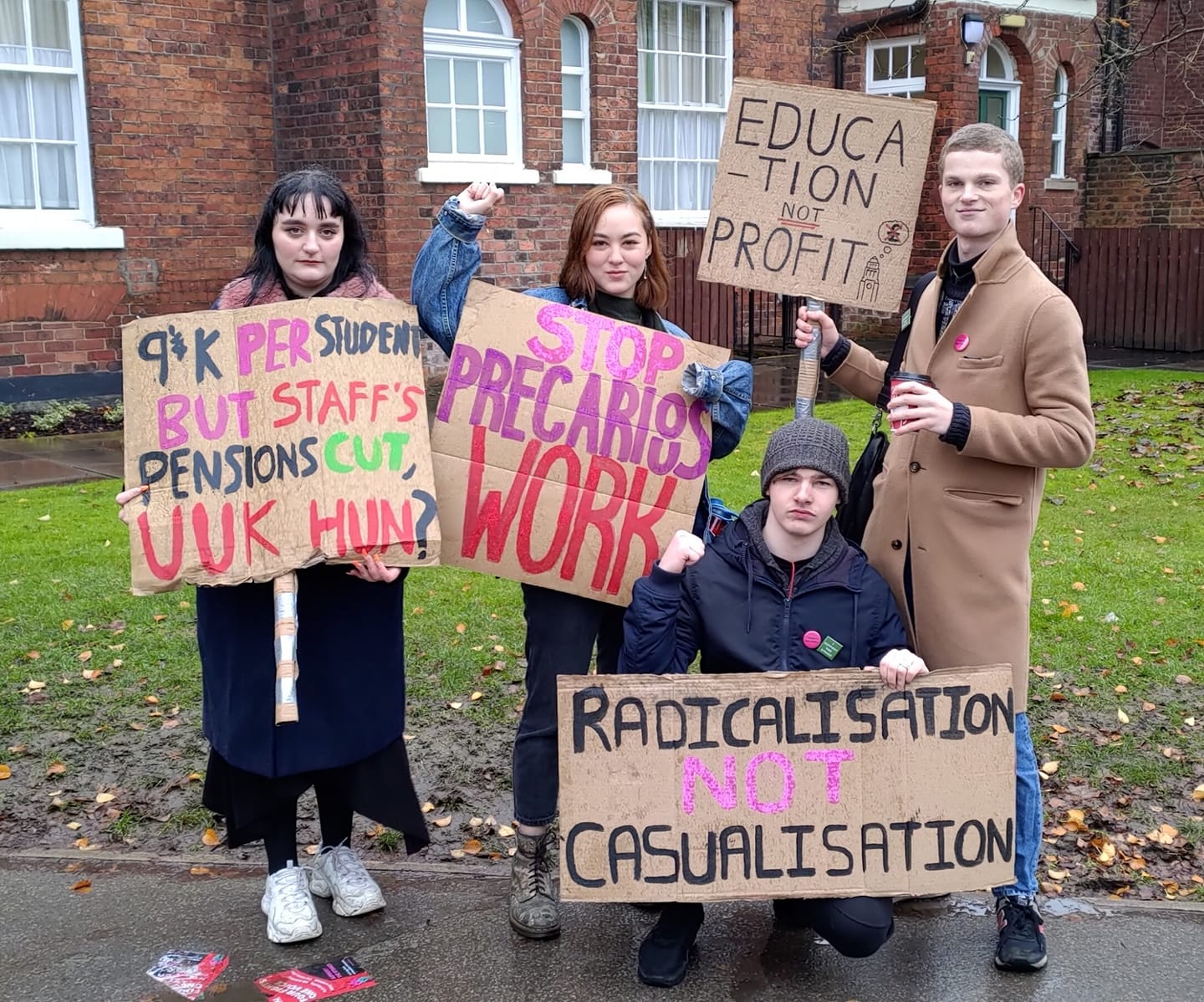

The recent UCU strike saw significant support from students. Students recognised that deteriorating working conditions directly affect them. In Leeds, the Marxist society mobilised for every day of the strike, fighting against the marketisation of higher education.

Every single morning, from November 25 to December 4, the iconic white steps of the Parkinson Building at the University of Leeds were full of striking lecturers, students, and higher education workers alike. This was as a result of UCU strike action, balloted in Leeds at the beginning of November and put into place at the end of the month.

Leeds University Marxist Society was present at the picket line every day – alongside Leeds Students Support UCU – to show solidarity with our striking lecturers. And when they were approached for comment, staff offered personal stories that vividly encapsulated the problems that plague higher education – not just in Leeds, but across the entire country: marketisation, casualisation, and exploitation.

Dignity and equality

The reasons for the UCU strike were fourfold. Firstly, the issue of pensions: the shift to a new pension scheme that could leave some staff thousands of pounds worse off at the end of their career. This is the same reason behind previous strike action in 2018.

But aside from pensions, the issue of the pay gap in many universities (including the University of Leeds) between members of staff – on the basis of gender, race, disability and class background – was constantly highlighted. One member of staff in front of the Business School told us that they had faced discrimination on multiple levels throughout their career.

The prevalence of precarious zero-hours contracts – and the difficulty of obtaining a more secure, full-time contract – was also a major sticking point. Some striking tutors on Cumberland Road told us that their contracts often meant they were not compensated for the amount of work they needed to do to prepare for teaching. Mental and physical health problems stemming from precarity and insecurity were also seemingly common.

Students and workers: Unite and fight!

Staff were quick to draw the link between their own working conditions and their students’ learning conditions. Simply put, if staff are stressed out – and even ill – as a result of their working conditions, then they will not be in the best frame of mind to guide their students and tutees.

Furthermore, deteriorating working conditions in higher education – a phenomenon which many staff said have remarked throughout their career, and particularly since the introduction of tuition fees in 2010 – mean that fewer students will be drawn to higher education as a potential career path, possibly leaving many faculties with a severe lack of staff and personnel. This will directly affect students in the future.

All of this was clearly understood by many students, who joined the strike at different points throughout the eight-day period. Those who spoke to us stressed that they do not agree with the commodification of education, and that the struggle of staff was also their fight. The chants “Students support staff on strike” and “Their working conditions are our learning conditions” reverberated far and wide.

Shame on you, LUU!

But the Leeds University Union (LUU) – which is supposed to represent the interests of students at the University of Leeds – was unfortunately not so clued up on this fact. Despite the NUS (National Union of Students) coming out nationally in favour of the strike action, the LUU remained neutral. Scandalously, they stated that their role was to give students the “right information” in regards to this “complex conflict.”

But the Leeds University Union (LUU) – which is supposed to represent the interests of students at the University of Leeds – was unfortunately not so clued up on this fact. Despite the NUS (National Union of Students) coming out nationally in favour of the strike action, the LUU remained neutral. Scandalously, they stated that their role was to give students the “right information” in regards to this “complex conflict.”

But this conflict is not complex. It is simple: the lecturers’ fight is our fight. Students should offer unconditional solidarity with their striking lecturers, and should support them in any way that they can. Hence why the chant “Shame on you, LUU” became so prevalent among students over the course of the strike.

To this end, around 20 students took part in a demonstration outside the LUU on Monday 2nd December, demanding that the Student Executive abandon their neutral stance. An agreement was met and a meeting was set up with several members of Leeds Students Support UCU on Thursday 4th December. But the results of this remain to be seen.

Advance and retreat

There was a certain degree of pessimism on the picket line, especially given that this is the second time that UCU members have struck in recent memory. One striking UCU member in front of the Laidlaw Library remarked that the situation that staff are in now is a result of neoliberalism, and that “it’s only going to get worse for those students who might become academics in the future”. They also added, “the situation is very bad, and I’m not very hopeful either”.

But this pessimism was not universal. In fact, striking members in front of the School of Electronic and Electrical Engineering affirmed that: “We are the university; the university is not the leadership, not the buildings, it is the people!” In other words, without the workers, the university is nothing.

Indeed, the effects of this current strike action have been felt far and wide. The Vice Chancellor of the University of Leeds has refused to come around the negotiating table and has stayed silent on the subject of the maintenance of pension deductions. But a militant mood was present on the picket line, and that will surely lead into the planned strike action for next February.

People’s stories on the picket line also demonstrate clearly a clarity of purpose and thought among members that will guide them in the struggle to come.

Democratize higher education!

But this struggle is only one piece of the national picture. All around the country, UCU members are fighting against the marketisation of higher education, exacerbated by the introduction of exorbitant tuition fees.

But this struggle is only one piece of the national picture. All around the country, UCU members are fighting against the marketisation of higher education, exacerbated by the introduction of exorbitant tuition fees.

Students and staff in all institutions need to come together and fight, because it is only through mass action that pressure can be put on university management. Institutions such as LUU also need to be pressured to provide solidarity to such struggles.

Yet, as long as universities and other higher education institutions are run like a business – and not like the centres of learning and self-fulfillment that they should be – the grievances of striking staff will never be resolved.

What is needed is for UCU members to raise their sights and demand the wholesale democratisation of higher education, placing control of these institutions in the hands of the workers who make them run in the first place.