A new report looks at measures that can be taken to address the enormous inequalities and social problems arising from the highly uneven distribution of land ownership in the UK. Nationalisation of all land must be the first step.

Last month saw the release of an independent report commissioned by the Labour Party, containing an array of proposals centred around the issue of land ownership in the UK. Land for the Many aims to “put land at the heart of political debate” and promises an “irreversible shift of wealth and power in favour of the many”.

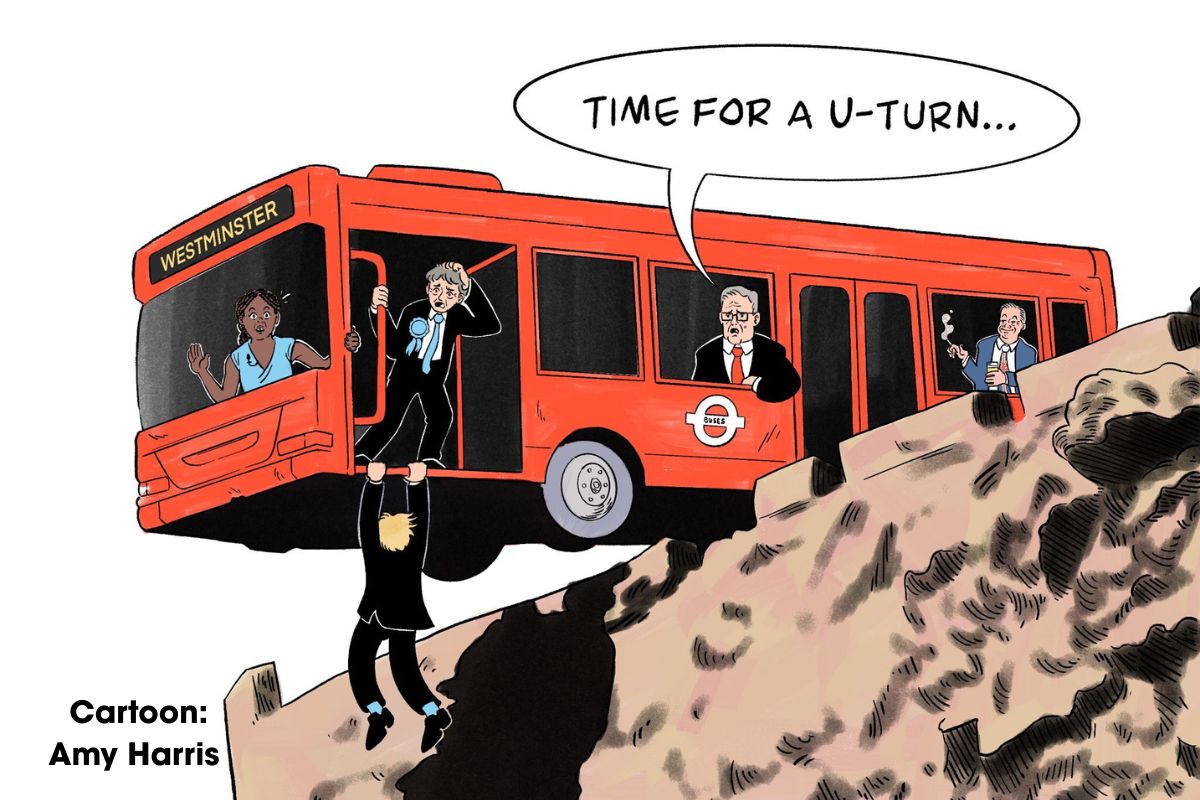

The report has certainly caused a stir among Tory MPs and the right-wing press. Conservative MP Priti Patel claimed that the report advocates “state-sponsored theft” and “is a confirmation that Labour would bring the policies of Venezuela to Britain”. Elsewhere, Daily Mail writer Alex Brummer commented that the report “is a move straight out of the Marxist playbook”.

But what exactly is being suggested? And just how radical are these proposals?

Why focus on land?

Firstly, we must ask: what is so important about land? Why does land matter so much? George Monbiot, the editor of the report, provides the answer to this, pointing out:

“Soaring inequality and exclusion; the massive cost of renting or buying a decent home; repeated financial crises, sparked by housing asset bubbles; the collapse of wildlife and ecosystems; the lack of public amenities – the way land is owned and controlled underlies them all.”

The facts confirm Monbiot’s claims. With regards to inequality, figures from Guy Shrubsole’s latest book Who Owns England? show that just 25,000 landowners – that’s 0.04% of the population! – own half of the land in England.

Furthermore, the report has found that, on average, 70% of the value of homes in the UK can be attributed to the value of the land upon which they are built. Given that the value of land has risen by 544% since 1995, it comes as no surprise that many Britons are struggling with rent payments, let alone buying their own home. Moreover, this can lead to working-class people being priced out of their own neighbourhoods, destroying entire communities in the process.

The report points the finger squarely at the financialisaton of land as the main factor behind this exorbitant rise in land value. In particular, Monbiot blames how successive governments have used tax exemptions and other advantages to turn land into a “speculative money machine”.

What is to be done?

In order to remedy the stark inequality in how land is owned and used, the report puts forward a range of policies dealing with everything from allotments and agriculture, to planning and property tax.

One of the explicit aims of the report is to suggest how a future Labour government could stabilise house prices, letting the wage-rent ratio catch up its “historic norm”. To achieve this, the report suggests measures to discourage predatory landlordism and property speculation.

Some notable positive policy proposals include capping annual rent increases at the rate of inflation, as well as abolishing council tax in favour of a progressive property tax, payable by owners rather than tenants. This property tax would be higher for properties declared vacant, meaning that empty homes would in theory be put to better use (although landlords would undoubtedly find some loophole to get around this).

Another key proposal is the creation of a ‘Community Participation Agency’. This initiative would see members of a local community chosen to be involved in planning procedures at every level, in a manner similar to jury service. The aim here is to bring a sense of agency and control to working-class communities, ensuring that everyone has a say over how the land around them is used.

The land compensation act

The policy proposal which has provoked the most ire from right-wing critics, however, is the suggested reform to the Land Compensation Act. This would allow new ‘Public Development Corporations’ to purchase land at its current value, as opposed to its potential future residential value. If put in place, this could reduce the cost of building affordable housing by up to 50%.

The policy proposal which has provoked the most ire from right-wing critics, however, is the suggested reform to the Land Compensation Act. This would allow new ‘Public Development Corporations’ to purchase land at its current value, as opposed to its potential future residential value. If put in place, this could reduce the cost of building affordable housing by up to 50%.

This proposal would certainly go a long way in alleviating the current housing crisis in Britain, whereby 1.1 million households are on social housing waiting lists. So why has it attracted so much criticism? Alex Brummer, a finance columnist for the Daily Mail, enlightens us:

“[This proposal] could trigger a financial crisis. Much of the nation’s potential land for development is owned by housebuilders, property companies and institutions such as insurers and pension funds.

“Some of these development holdings will have been bought or financed on credit from the banks. If land values plummet, banks will be left with a black hole on their books.

“A lending freeze might follow, bringing commerce to a shuddering halt, since credit is what keeps corporate Britain moving. That could lead to cascading business closures and a return of large scale unemployment.”

Amidst the hysterical sensationalism that is intended here, there lies a kernel of truth in what Brummer is saying. British capitalism – like much of the world economy – is now largely driven by rent-seekers and speculators. And this suggested proposal would be a massive hit to the parasitic profits of the bankers and financiers. This, in turn, would propagate chaos through the already-fragile financial system – one which is on the brink of another major slump.

Again, therefore, we see how even a relatively mild reform would quickly come up against the limits of the capitalist system – a system in which the economy and production are based solely on the profits of the few, and not the needs of the many.

Resistance to reforms

All of the suggestions outlined in Land for the Many, if enacted, would indeed bring big benefits to working-class communities, providing an economic shift in society away from the rich and powerful, and in favour of workers and youth. But, like with all genuine reforms under capitalism, the question is: how can these demands be achieved in practice?

All of the suggestions outlined in Land for the Many, if enacted, would indeed bring big benefits to working-class communities, providing an economic shift in society away from the rich and powerful, and in favour of workers and youth. But, like with all genuine reforms under capitalism, the question is: how can these demands be achieved in practice?

If a Labour government attempted to force the purchase of land at a sub-market value, this would be met with strong resistance from the landowners and financiers, whose profits rely on the continuation of the current laissez-faire economy.

As Brummer alludes to, we may expect to see capital flight, alongside all manner of political and economic sabotage, either to force a Labour government to submit to the diktats of the City of London; or, more likely, to bring down the government altogether.

It is clear, therefore, that these proposed reforms – whilst welcomed – do not go far enough. The report aims to find a “balance between the four major pillars of the economy: the market, state, household and commons”. But it fails to understand that the capitalist market is antagonistic to common ownership, and will always seek to undermine it.

Nationalise the land!

There can be no ‘balance’ in a system marked by periodic crises, each more extreme than the last. Privatisation and the profit motive have been a disaster for the working class, causing nothing but crises, bubbles, and shortages. The only way forward for workers and youth is a socialist economic plan that tackles the problems of land, housing, and infrastructure all in one fell swoop.

There can be no ‘balance’ in a system marked by periodic crises, each more extreme than the last. Privatisation and the profit motive have been a disaster for the working class, causing nothing but crises, bubbles, and shortages. The only way forward for workers and youth is a socialist economic plan that tackles the problems of land, housing, and infrastructure all in one fell swoop.

To bring about any real change, therefore, we have to take control out of the hands of the wealthy elite at the top. This ultimately comes down to a question of ownership. After all, as the old saying goes: you cannot plan what you do not control; and you cannot control what you do not own.

Instead of attempting to mediate between the interests of the capitalists and those of the working class, what we need are clear socialist policies. If Labour is to commit itself to a radical programme of mass social housing construction and local development, then we need to tell the truth: this can only be achieved with the nationalisation of all land.

If this was carried through, then land could be democratically managed by the working class for the interests of society, and not by a tiny clique of elite landowners. Only then could we protect our communities and green spaces from the onslaught of capital.

Furthermore, to prevent the flight of capital that would ensue if a Corbyn Labour government encroached upon the free market, a policy of expropriation is required.

This means not only nationalising the land, but also nationalising the banks, utilities, and major construction companies. This would free up billions of pounds that could be invested into socially useful projects, and would allow for the construction and provision of decent housing for all.

These are the kind of radical ideas that Labour must campaign on. Rather than tinkering at the edges, Labour must mobilise the mass of workers and youth in a determined fight for a bold socialist programme.