Recent ballots for strike action over pay amongst UCU and Unison members have fallen due to demoralisation. This is the result of passivity and weakness from union leaders.

Over the last two months, two major trade unions in the Higher Education (HE) sector – UCU and Unison – have been balloting their members in Higher Education on strike action over pay.

While they were seperate ballots with different demands, both centred around the issue of below-inflation pay rises over many years, and were timed for potential joint strike action.

Universities have already seen large strikes this year, in the form of the UCU action over pensions. Despite a huge amount of energy from UCU activists, this struggle was ultimately betrayed by the union leadership, who sold out members by accepting a botched deal.

The potential for a second wave was a worrying prospect for HE management. This time the action would not only have involved academics in the UCU, but also support staff represented by Unison: lower-paid workers such as cleaners, catering staff, groundskeepers, and admin workers.

This often forgotten layer of staff are the real backbone of the university sector. The potential for both unions to walk out on strike at the same time was not something that management could risk.

Demoralisation

Fortunately for the bosses, the recent mood amongst workers on the ground has been one of demoralisation. After the sellout of the previous UCU strike, many academic staff don’t have the wind in their sails for another battle.

Fortunately for the bosses, the recent mood amongst workers on the ground has been one of demoralisation. After the sellout of the previous UCU strike, many academic staff don’t have the wind in their sails for another battle.

Amongst Unison members, meanwhile, trust in the leadership to put up a genuine fight isn’t much better. After years of accepting below-inflation pay rises and passively allowing attacks on workers in all the sectors the union represents, there is little belief that a strike would reap any real rewards.

At the UEA (University of East Anglia) in Norwich, one member of catering staff told me that she had actually stopped her Unison membership a couple of years ago because, in her words, “they always just lie down and take it”.

This worker, and most others, had heard nothing about the pay campaign before I spoke to them about it.

As a result of this demoralised mood and lack of fighting leadership, turnout in both the UCU and Unison ballots was low, failing to meet the 50% minimum required by the Tories’ anti-trade union legislation.

In Unison, only 31% of ballot papers were returned – although 61.9% of those voted in favour of strike action. The UCU ballot fell for the same reason, despite 85% of members in FE colleges and 69% of members in universities voting to back strike action.

Power of the workers

To stack the scales in their favour, UEA management decided to announce their own meagre pay rise – below what the union had been demanding – in an attempt to pacify and placade workers, and to paint themselves as a generous, caring employer.

To stack the scales in their favour, UEA management decided to announce their own meagre pay rise – below what the union had been demanding – in an attempt to pacify and placade workers, and to paint themselves as a generous, caring employer.

Management didn’t mention the strike ballot in this announcement. Instead, they presented their offer as a benevolent gift; a reward that we should all be grateful for.

This not only shows the complete underhandedness of university management, but also illustrates clearly the power of the working class. In this case, even the threat of a strike was enough to force the hand of the bosses.

Broken system

Votes like these strike ballots are just a snapshot of a moving picture. The issues facing workers in the HE sector aren’t going to go away because of one failed ballot.

Votes like these strike ballots are just a snapshot of a moving picture. The issues facing workers in the HE sector aren’t going to go away because of one failed ballot.

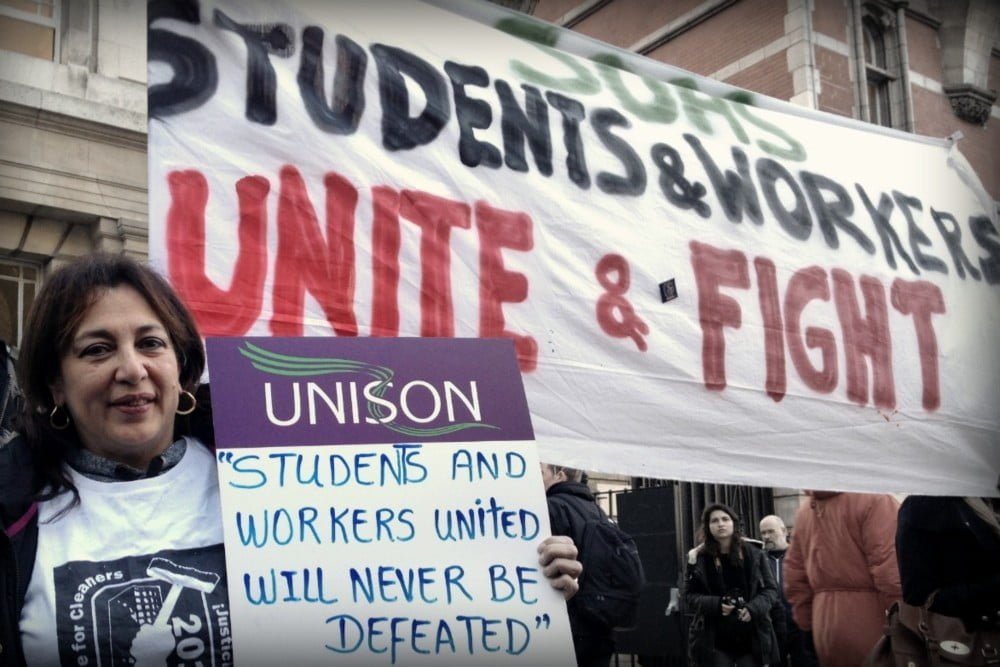

The last eight years have seen dramatic movements by students and staff alike in universities over a range of issues: from student fee hikes back in 2010; to action over the outsourcing of support staff like cleaners; to the more recent UCU pensions dispute.

Students and workers have moved into action with or without the permission of the leadership of the large trade unions. If university management thinks these recent ballot results are the end of the story, they are sorely mistaken.

What connects all of these issues and struggles by workers and students is the crisis of the HE sector – a crisis created by a decade of cuts, privatisation, and marketisation.

This, in turn, is the product of the wider crisis of capitalism and the resultant austerity, which has forced universities and other public services to increasingly attack workers and users.

Until this broken system is overthrown, these disputes will continue.