Due to the privatisation of the telecoms industry, internet infrastructure in Britain has been outdated for decades. Monopoly conditions allow company bosses to make a killing from poor quality infrastructure. Labour’s recent proposals are a good start.

Labour’s proposal to rollout free fibre-optic broadband to every home and business across the country by 2030 has struck fear into the heart of the telecoms monopoly bosses.

Confirmed in the ‘Digital, Culture, Media and Sport’ section of the manifesto, the policy includes:

- An investment of £20.3bn to bring the UK’s “full-fibre” coverage from 8% to 100%.

- Nationalisation of BT’s physical network subsidiary Openreach.

- Part-nationalisation of BT itself.

- A tax on multinational internet giants (Amazon, Google, Facebook, etc.) to pay for the setup and maintenance of the proposed network.

This plan would be a massive step forward in revitalising the backwater state of UK internet telecommunications. More fundamentally, it would shift control of the country’s internet infrastructure into the hands of the people it connects.

British Broadband

The proposed new entity to manage the rollout of this free fibre network, ‘British Broadband’ (BB), would be comprised of two arms: British Digital Infrastructure (BDI) and British Broadband Services (BBS).

BDI, formed from the nationalised BT Openreach, would rollout and maintain the physical fibre cabling and infrastructure. BBS, formed from the merging of a part-nationalised BT Enterprise (which retails broadband to businesses) and BT Consumer (which retails broadband to individuals), would deliver free broadband that connects users to the internet over BDI’s physical network.

An overly simplistic analogy would be that BDI is tasked with building and improving the UK’s digital road system, whilst BBS is tasked with providing a free digital postal service that takes advantage of these roads.

Infrastructure

As far back as the 1970s, the issue of copper cabling being insufficient for delivering broadband was well known. In an interview with TechRadar, former BT Chief Technology Officer, Dr Peter Cochrane, outlined how there had been a programme started in 1979 to roll out full-fibre internet connections across the country.

As far back as the 1970s, the issue of copper cabling being insufficient for delivering broadband was well known. In an interview with TechRadar, former BT Chief Technology Officer, Dr Peter Cochrane, outlined how there had been a programme started in 1979 to roll out full-fibre internet connections across the country.

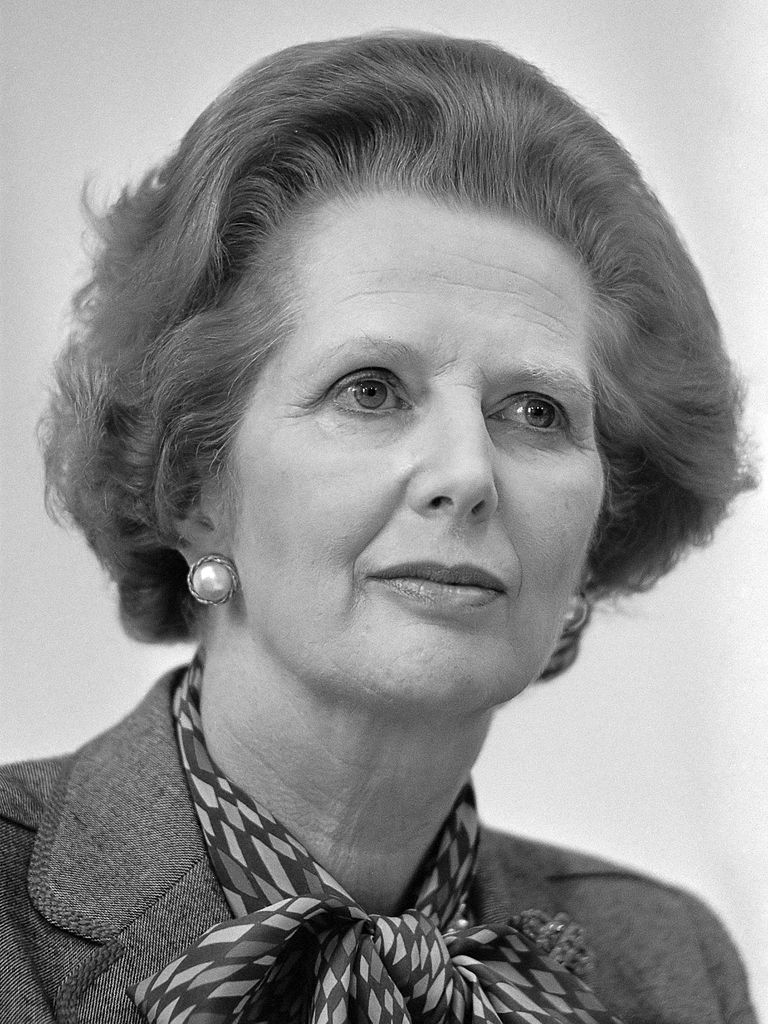

Margaret Thatcher, however, later privatised BT. And in 1990, her Tory government blocked the roll out of the full-fibre network on the grounds that it stifled competition. These actions have meant UK internet infrastructure has languished for almost three decades.

Currently the majority of ‘last mile’ cables that connect homes to the internet remain copper telephone wires. Only 8% of homes have a direct FTTH (Fibre To The Home) connection. This is embarrassingly low: the UK placed last out of 34 countries in a table published by FTTH Council Europe earlier this year. On the global stage, it is far behind the likes of Japan, Korea, and Singapore.

The reason for this stagnation is that BT Openreach has a monopoly over the existing copper infrastructure. The corporation therefore makes billions renting out its barely-maintained lines to broadband providers.

Unaccountable to the general public, the company has no interest in replacing copper lines or laying new fibre lines. Why would Openreach bosses invest when they are making super-profits out of the current situation?

The pressure to address this problem has resulted in the Conservatives offering £400m to private companies to provide full-fibre cabling. Boris Johnson has pledged a further £5 billion if he were to be elected.

Of course private companies like Openreach and Virgin Media are happy to take this money. But they will only cherry pick areas that will make them the biggest returns. Furthermore, ISPs will charge higher rates for fibre connections, keeping it as a premium option rather than making it available to all.

Re-nationalising this infrastructure is the only way out of this mess – and for one simple reason: no company is going to improve rural internet connectivity, lay new lines, or update outdated copper lines unless it makes them more profit.

Free broadband

The promise of providing not only a free fibre connection, but also a free broadband connection over that fibre has proved to be a massive upset for the privatised telecoms industry.

Free broadband access is not radical – it is necessary. Access to the internet is a basic need for participation in today’s society. But for many in the UK it represents one bill too many.

In 2017, Ofcom reported 47% of people on a low income don’t have access to broadband internet at home. And yet access to the internet is a requirement for Universal Credit sign ups and claims. It is therefore ridiculous to claim that an internet connection is a luxury.

Internet Service Providers (ISPs) are therefore in a hugely advantageous position, providing a service that everyone in the country needs for daily life. Ofcom’s 2018 Communications Market Report estimated the telecom industry’s revenue to be £35.6bn in 2017. This is all based off of a parasitic business model.

After an initial investment in physical hardware, ISPs can start selling their services. For each customer they will likely need to rent the physical access network, as the cost of laying new lines is prohibitively expensive. There are other running costs, such as equipment replacement and ‘peering’ costs to transfer traffic internationally. But these costs don’t stack up to much next to the mountains of revenue that start flowing in once you’ve acquired a sizeable customer base.

Even so, line rental and running costs are paid for by the end user as part of their £20-50 per month package. After that, almost the entirety of a monthly broadband bill is mark up – essentially a monopoly rent to be funnelled into the pockets of executives and shareholders. Most reinvestment will be into advertising to acquire more users, rather than the improvement of services.

A free national broadband would be the death knell for this business model. The vast majority of users have as much loyalty to their ISP as their ISP does to them.

Unsurprisingly, these parasites have been in uproar about the potential disruption to their long running scam. They cannot compete with a free broadband service, because they fundamentally provide nothing of value beyond a basic internet connection.

.@BorisJohnson’s version of broadband rollout will be delivered with likes of @Virgin, who’ll cherry pick profitable bits of the network & ask for huge Govt subsidies for rollout to rural areas. Old fashioned ideology of privatisation is slowing us down: pic.twitter.com/srSB0ho8Ll

— Laura Pidcock (@LauraPidcockMP) November 26, 2019

Need to go further

As with Labour’s other nationalisation plans, such as those for the postal service and railways, the nationalisation of telecommunications will face huge opposition from the bosses that control that industry.

The chief of Openreach has already made claims that the cost of Labour’s plans will end up being more like £100bn. TechUK, a group of industry leaders, have put out a statement saying the plan would damage ‘innovation’ in the telecoms sector.

Labour has put forward increased taxation as a way to pay for these demands. But these companies already own an army of lawyers and accountants to hide their profits. If Labour follows this plan in the belief that the ruling class will go along with it without objection and sabotage, the endeavour will be shipwrecked before it begins.

To achieve a free full-fibre network, it is necessary to go further. Not only select chunks of BT, but the whole of the rigged telecoms network should be nationalised. This must be done without compensation – the parasitic providers have already made billions from exploiting their workers and customers.

Major construction companies should also be nationalised without compensation. Without this, the companies tasked to pull up roads and lay cables would either siphon public money into their own pockets, or would outright refuse if there isn’t enough profit to be made. The Carillion scandal stands as a powerful example of this fact.

But crucially, the control of all sectors nationalised by Labour must be run democratically by workers, as part of a rational socialist plan for the economy. Rather than unaccountable boards of former executives and bureaucrats, the working class should have control over how our telecoms are managed.

With these steps, Labour would be able to provide a communication network in line with the promises of the early internet pioneers – a network that gives equal access to all, encourages communication, and can unite rather than divide.