As a result of Tory austerity, local public services are being cut to the bone. But it is Labour councils that are implementing these cuts, hiding behind the failed strategy of the so-called “dented shield”. Rather than passing on the cuts, Labour councillors should learn from the militant example of Liverpool and fight back.

Almost every day in the Tory press and media we can see letters, interviews and comment relating to the devastation of local authorities, both under New Labour and to the present day under the Tory government. Many of these comments come from both Labour councillors and council leaders around the country.

Inner London councils have lost 40% of their central government funding since 2010. Think Tank London reveals that core funding from central government will fall in real terms by 63% – equivalent to £33.9 billion – over the decade to 2019-20. This will lead to the closure of youth services, children centres, libraries, swimming baths, day centres and many other facilities needed by working class families – not to mention the jobs they provided. This pattern is repeated in virtually every town and city in Britain.

Alongside this devastation, spreading like a plague, we have luxury property developments – fuelled by speculators and built for multi-millionaires – rising up everywhere. These are bought to let by spivs and investors (both at home and abroad), with blocks of penthouses built as investments, only to stand empty, while around them rough sleepers have to tough it out on the streets below in ever-growing numbers.

Much of this sort of development has the blessing of Labour councillors, as a result of budgets being slashed by both Tory and New Labour governments. Property developers have happily stepped in to fill the gap. Council estates and other buildings have been sold off and demolished and luxury flats have taken their place. Speculators see this as fair game and Labour councils – rather than fighting the cuts – have taken the easy route and caved in. This for the most part has been Labour policy nationally.

All Labour councils are stuck in this predicament, complaining and asking rhetorically: “what can we do?” They plead to the Tory government, saying “the Government must act!” etc., etc. But this is the condemned pleading to the hangman for help while he prepares the noose. At the same time they help carry through the Tories’ austerity policies with a vengeance.

Liverpool and Thatcher

This is a repeat of the situation councils faced in the 1980s, when Margaret Thatcher started on her rampage of austerity and rate capping of council budgets. Neil Kinnock, the then Labour leader, came up with the cowardly policy of the “dented shield” tactic, which basically meant “accept the cuts and do your best”. Most labour councils did just that and crumbled and prepared to accept the cuts. The exception was Liverpool City Council, in which over many years Militant supporters had put down deep roots in the local labour movement and specifically the council.

This is a repeat of the situation councils faced in the 1980s, when Margaret Thatcher started on her rampage of austerity and rate capping of council budgets. Neil Kinnock, the then Labour leader, came up with the cowardly policy of the “dented shield” tactic, which basically meant “accept the cuts and do your best”. Most labour councils did just that and crumbled and prepared to accept the cuts. The exception was Liverpool City Council, in which over many years Militant supporters had put down deep roots in the local labour movement and specifically the council.

As a result, the Militant-supporting Labour Party eventually succeeded in ousting the Liberals from control of Liverpool council. The full weight of Thatcher’s venom was not felt in Liverpool at first. But after the miners’ strike ended – betrayed with the help of the TUC leaders – Thatcher turned on Liverpool. For a generation Liverpool had been a thorn in the side of the ruling class, always troublesome and rebellious, and once again they were defying the “Iron Lady” and her government.

A number of labour councils had verbally talked of following the stand of Liverpool, such as Sheffield under David Blunkett and Ted Knight in Lambeth London. But their leaders soon wavered then backed off, with Lambeth falling last. Other councils hinted at defiance, but nothing was prepared, and none were prepared to follow Liverpool’s lead

It wasn’t just a question of whose will dominated; it was a case that the Liverpool councillors had built solid support and had undertaken a whole new house building programme, building homes for working class families, with new day nurseries and sports centres, and creating genuine jobs for local people.

Chorus of condemnation

The forces of reaction soon ganged up on the council, with opponents in Liverpool and across the country lining up with Thatcher and the Tory media – from the Sun and the Mail on the right, to the liberal Guardian and “labour” Daily Mirror – and the Establishment, all baying for blood.

Kinnock and Roy Hattersley and nearly all the train union leaders and the TUC caved in and supported this onslaught, although they didn’t need much encouragement. Every distortion and outright slander was levelled at the Liverpool council. The newspapers where filled with lurid stories of “Marxist and Trotskyist plots and takeovers”, unsubstantiated tales of alleged ‘violence’, all poured out of rage against the Marxists of the Militant and supporters of the council’s stand – that is, against all those steeled and determined to lead the fight.

This howling crescendo of poison from the bourgeoisie was joined in by other on the Left, such as the Communist Party, Socialist Workers Party and the Workers Revolutionary Party, alongside the soft lefts. Naturally the Liverpool Liberals joined in, as they had a particular spleen to vent after losing control of the council.

Celebrities followed where others had led. Jimmy Saville took some time off from his busy BBC-subsidised schedule of abusing kids and necrophilia visits to various hospital morgues in order to lay into the Liverpool council. Jimmy Tarbuck joined in the abuse too. Alan Bleasdale, the author of the popular TV series Boys from the Black Stuff about Liverpool tarmacking gangs, sadly produced G.B.H, a nasty Channel 4 hatchet job “modelled” on Derek Hatton, the then deputy leader of the council. The actor Robert Lindsay (better known for his somewhat pathetic portrayal of Tooting Popular Front leader “Wolfe Smith”) played Michael Murray, a parody of Hatton; his portrayal of said leader was, as with his role as TPF leader Citizen Smith, pretty naff and also not particularly funny. Finally, Paul McCartney, to his shame, condemned the council and for good measure added to his list the defeated miners and Liverpool teachers.

Absolutely nothing was spared in this vast tidal wave of class hatred, with even the church leaders weighing in as well.

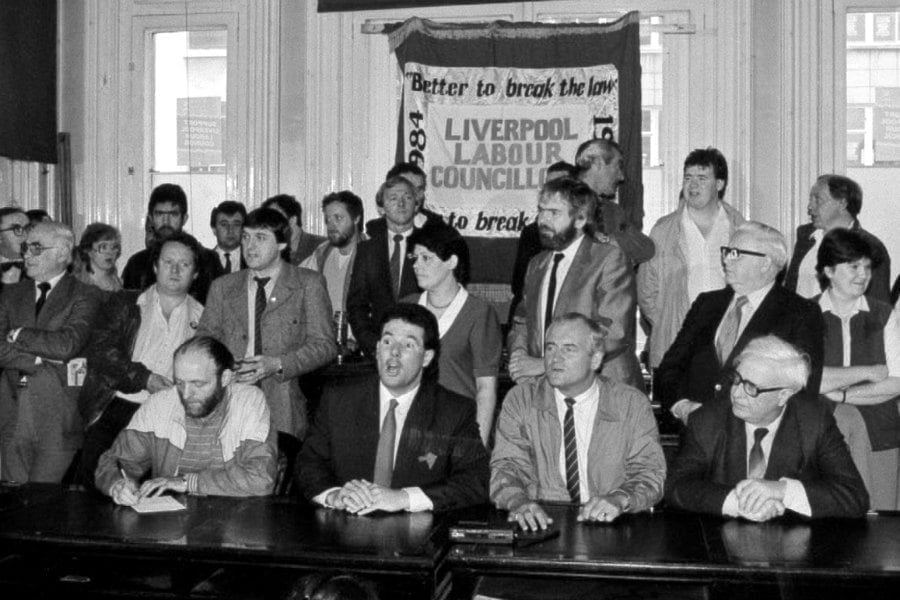

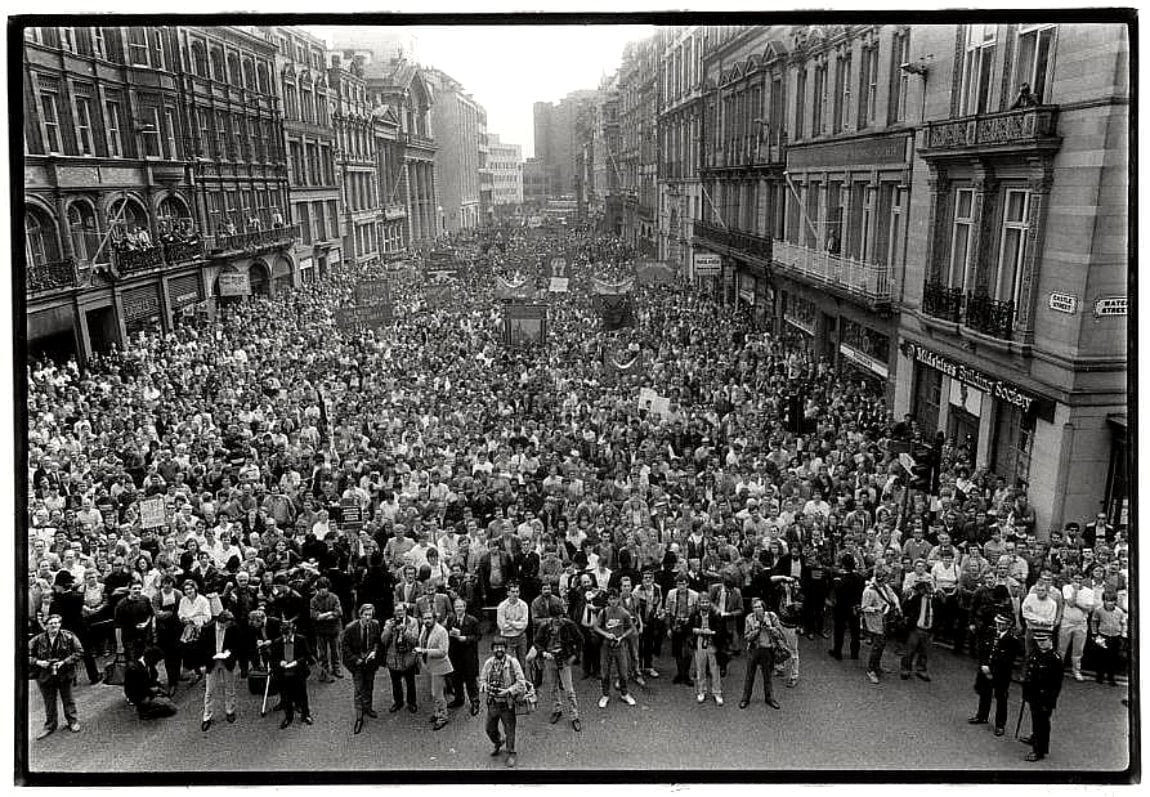

Workers and youth come out in support of Liverpool City Council in 1985 (photo by Dave Sinclair)

Winning the battle; losing the war

Against this the Liverpool council stood firm – their ace card being the mass support of the Liverpool labour movement and the wider population, who had not only seen but experienced also the council programme of house building. They rallied to the Liverpool council’s defence. I experienced this myself, going up to Liverpool a few times, and got the indication of this on the doorstep as people spoke about this being a real fighting socialist Labour council in action – not only in terms of its own struggle, but also in the help they gave the miners in their tremendous battle against Thatcher and Ian McGregor and the National Coal Board. Against all odds the Liverpool council won a momentous victory and won major concessions from Thatcher in 1984.

But winning a great battle is not the same as winning the war. Without the active support of similar movements around the country, and without support from trade union and Labour leaders, Liverpool council remained isolated. In early 1985, the miner strike ended for same fundamental reason as that of the Liverpool struggle. Betrayed by the craven cowardice and treachery of the so-called leaders of the labour movement, the council struggled on alone. The real reason these struggles were defeated, contrary to the myths peddled today about Thatcher crushing them, was precisely due to the betrayal of the then Labour leaders.

Liverpool’s momentous two-year battle with the Tories has been buried underneath mountains of lies, which still come out every time the subject is aired in the media today. They stood against everything thrown at them, including legal threats such surcharging and dismissal from office and personal legal threats to seize their homes and personal possessions. These threats were met with mass mobilisations of council workers, tenants and other council supporters, and at its height the council engendered massive sympathy up and down the country. Graham Stringer, then on the Left and leader of Manchester city council, stated that the Liverpool stand had helped Labour win the council decisively in Manchester. In other parts of the country, other Militant supporters were elected as councillors on the same programme of determined opposition to cuts, in clear recognition of Liverpool’s fighting strategy.

Unfortunately this bold stand wasn’t reflected by the Labour leaders. With the ruling class applying the financial screws, Kinnock and the soft lefts on the NEC implemented the expulsion of nine of the leading councillors who where either Militant supporters or sympathetic to the bold stand taken by the Militant. These people, who had between them 141 years of Labour party membership, were thrown out of the party while the state itself waded in, throwing them out of office and slapping on surcharges £106,000 plus fines and £242,000 “costs” to the district auditor. The court judge needed to show that they were completely unbiased and even ended by attacking each of the councillors individually in court – this attack being led by Lord Justice Lawton, who incidentally (as was pointed out at the time) was a candidate for the British Union of Fascists in Hammersmith in 1936; although in the interests of democracy and impartiality this was completely ignored.

Poplar and Clay Cross

Liverpool’s stand in 1984-86 followed very much in the footsteps of the earlier brave fight of a small Derbyshire town called Clay Cross against the Tory government of Ted heath in the 1970s, and also the stand of George Lansbury and the Poplar Council in the East End of London in the 1920s.

In Clay Cross, the council was attacked due to its refusal to implement the 1972 Housing Finance Act, which demanded steep increases of the rents of council housing. Heath’s government demanded that the rents should increase by £1 a week from October 1972. The council was one of several to show defiance against the Act, and one of three to be ordered to comply by the Department of the Environment in November 1972 (the others being Eccles and Halstead). Clay Cross Urban District Council (UDC) was threatened with an audit in December 1972. The constituency Labour Party, demonstrating an earlier example of the “dented shield” in action, barred the eleven councilors from its list of approved candidates. This then allowed the District Auditor to order the eleven Labour Party councilors to pay a surcharge of £635 each in January 1973, finding them “guilty of negligence and misconduct”. It was this struggle which raised Dennis Skinner to prominence.

The UDC made an appeal to the High Court in March 1973. The surcharge was upheld by the High Court on 30 July 1973, which also added a further £2,000 legal cost to their bill, as well as barring them from public office for five years. The council further defied the authorities (the Pay Board) in August, when they decided to increase council workers’ earnings. This provoked a further dispute with NALGO. Ultimately, the dispute became moot, with the replacement of Clay Cross UDC with the North East Derbyshire District Council from 1 April 1974. The councillors were made bankrupt in 1975. All this foreshadowed what happened in Liverpool 12 years later.

The Poplar councillors stand in the 1920s against the rates mobilised tens-of-thousands of East-enders, with councillors sent to jail for defying the government dictates on rate rises. The pressure of the local population and the wider labour movement lead to the councillors being released and a victory for the working class at that time.

Labour councils must fight the cuts!

Today, Labour councils are facing almost endless austerity and continuous attacks, and this is talked about in terms of a way of life for the councils. Up and down the country the Tories’ austerity is passed on with comments but not much else. The Tories – as the primary representatives of the capitalist class – have set out to end all the social gains that have been won since the Second World War. This is not just the Tories being “nasty”, as is often said (although with some individuals there is a touch of the personal about these things), but is a deep reflection of the collapse of the capitalist system and the demands it imposes as the social system implodes.

Today, Labour councils are facing almost endless austerity and continuous attacks, and this is talked about in terms of a way of life for the councils. Up and down the country the Tories’ austerity is passed on with comments but not much else. The Tories – as the primary representatives of the capitalist class – have set out to end all the social gains that have been won since the Second World War. This is not just the Tories being “nasty”, as is often said (although with some individuals there is a touch of the personal about these things), but is a deep reflection of the collapse of the capitalist system and the demands it imposes as the social system implodes.

As we have witnessed in recent years, the Tory government, Tory-Liberal Coalition, and New Labour have all pursued an austerity agenda with a vengeance, and Labour councils have acted as executioners of cuts and privatisations, selling off council estates and implementing the bedroom tax with the plaintive wail that “we have no choice”. Many Labour councillors who have raised opposition have been dealt with by having the whip removed and/or threatened in some cases with expulsion.

John McDonnell was asked last year if illegal budgets could be used by Labour councils. His reply was “that to do so would bring the Tory government commissioners in!” So it clear that the Liverpool attitude is not present here.

The fact is that the issue of attacks on councils could be ended. What if a whole number of councils united on a programme of open defiance? How would the Tories cope then? Or are Labour councils forever to carry out the Tories’ austerity, continuing until there are no more services left to defend.

It is hardly surprising that in recent local elections many traditional Labour voters didn’t support them. If we are told that the cupboard is empty, then why vote? With the possibility of a Tory general election victory on the cards, Labour councils will soon come under further pressure.

The struggle of Liverpool, Clay Cross and Poplar councils are a dead letter to the Blairites and the other deadwood sitting on councils, temporarily occupying seats that could be filled by more determined fighting working class representatives.

Although these dry-rotted councillors may not be aware of these heroic struggles, the labour movement itself will not stand on its laurels, and the actions of these pioneering councils will be revived. Although things might look somewhat black at the moment, it will be the crack of the Tory whip on councils that will invite a determined fightback; eventually, despite the current lack of leadership, councils will be forced to rise to the challenge.

It is transparent that there is a need for a fightback in every council in Britain; a crying need that can only be met by united and militant action if it is to succeed. Uniting trade unionists, tenants and all users of council services with a clear programme and fighting leadership – as was clearly shown by Liverpool, Clay Cross, and Poplar councils – we can start to roll back the cuts and austerity.

This would be the start of a campaign to clear out the Tories and their shadows in the Labour Party establishment – and of a struggle to remove this rotten social system and create a socialist society.