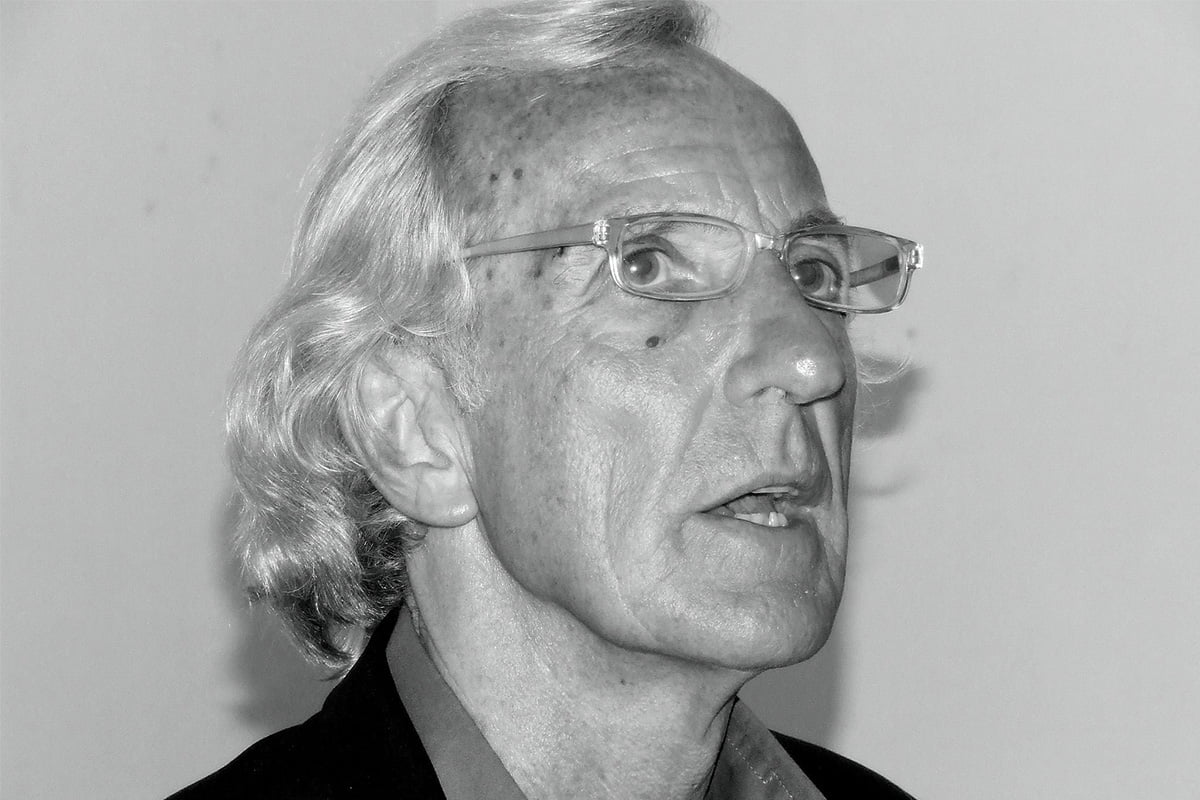

John Pilger – Australian-born, UK-based, anti-imperialist journalist and documentarian – passed away last year on 30 December, abruptly ending a career that spanned over half a century and the entire globe.

Throughout his life’s work, Pilger’s intention was always to expose western imperialism: an objective for which he never apologised, and for which the capitalists and their mouthpieces never forgave him.

Pilger once said that the role of a journalist should, first and foremost, be to hold a mirror to their own society; or, to put it another way: the main enemy is always at home.

Pilger’s work exposed the fact that violence and brutality abroad could usually be traced back to the comfortable cushions of the White House and Downing Street.

Too many journalists are willing to accept at face value what they are told by their ruling classes about foreign policy – as Pilger put it, “to see humanity in terms of its usefulness to ‘our’ interests”.

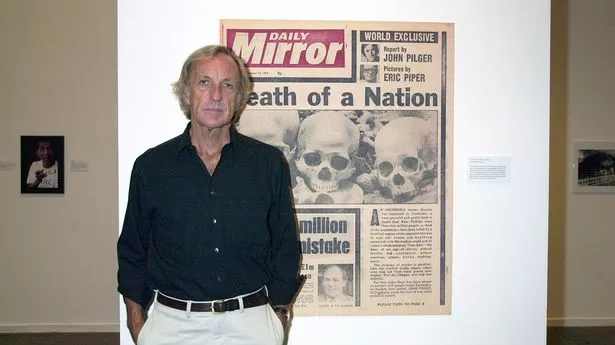

For him, the opposite was true. He dug into all of the dirty secrets that the British government would rather have kept buried: from its sale of arms to Suharto’s genocidal regime in East Timor (Death of a Nation, 1994); to the use of conspiracy charges to shut down dissent in the UK (A Nod and A Wink, 1975).

Giving voice to the voiceless

His documentaries always followed a similar format. First and foremost, Pilger would strive to be “at the scene of the crime”.

Rather than relying on second-hand information, he would travel to the country or region in question, and directly interview the subjects of his documentary. His aim was not to put words into their mouths, but to expose the injustices that these people had experienced first hand.

He would then speak to the criminals themselves: from former CIA chiefs and Israeli policy advisors, to profiteering businessmen, watching as they scrambled to justify their actions.

An immensely skilled interviewer, Pilger was also a fantastic storyteller, able to pull together all the threads of a scandal effortlessly.

Pilger cut his teeth in the arena of South-East Asia during and after the Vietnam War, covering stories that must have made him extremely unpopular amongst the US top brass. He documented the collapse of morale amongst American soldiers, and the fact that some were even killing their own officers (A Quiet War, 1970).

He was also one of the first journalists to enter Cambodia after the rise of the Khmer Rouge.

At the time, propagandists aimed (and still aim today) to write off the rise of Pol Pot as another folly of communism. Pilger’s documentary Year Zero: Cambodia (1975) explains how the basis for Pot coming to power, however, had been laid by the US bombing Cambodia “back to the stone age” during the Vietnam War – actions concealed from the public at the time.

Against the Empire

It was through seeing the horrors of Vietnam and Cambodia that Pilger became such a staunch critic of US imperialism. He understood, unlike many journalists, that American foreign policy had nothing to do with defending democracy. On the contrary, the US Empire gleefully trampled over democracy in the defence of its capitalist interests.

One of Pilger’s most important works in this vein was The War on Democracy (2007), which revealed the scale and breadth of US intervention against democratically elected governments in Latin America.

The documentary is framed around Pilger’s visit to Venezuela – at that point run by President Hugo Chavez, a man the White House was desperate to be rid of.

Pilger showed extreme respect and admiration for the Venezuelan workers and their aspirations. These were expressed through the Chavez presidency, which used Venezuela’s oil wealth to fund major social reforms.

He went into the barrios and interviewed workers and the poor; he filmed the night classes where 97-year-olds were being taught to read, the clinics where ordinary people were seeing doctors for the first time in their lives, and the subsidised grocery stores where workers were shopping.

These observations were contrasted with the lifestyle and opinions of Venezuela’s capitalist class, interviewed in the same documentary.

One such capitalist, in his ornate living room, said without hesitation: “Miami is our second home. We were so rich, we went to Miami and bought houses, bungalows, yachts, cars – we were the owners of Miami. So we are very US-minded.”

Needless to say, these local parasites resented Chavez for wresting control of the state-owned oil company from the pro-multinational bureaucrats, almost as much as the US did.

Pilger’s documentary also gave a remarkable blow-by-blow account of the 2002 coup against Chavez, with staged protests that culminated in civilian deaths, as well as emergency broadcast of counter-revolutionary generals, later exposed to have been filmed before any incidents took place.

The film depicts the kidnap of Chavez, and the total liquidation of the constitution in just two days – all conducted with perverse applause for Venezuela’s capitalist class and the West.

The movement of the masses onto the streets of Venezuela, which defeated the coup, is clearly shown in the documentary as the victory of the oppressed and a defence of democracy – completely the opposite of how it was being portrayed elsewhere.

Pilger always strived to put the events that he was covering in their context, and explain them.

This was done remarkably well in The War on Democracy. Pilger traced the history of US-backed coups: from Guatemala to Nicaragua, Chile, and Bolivia. He spoke directly to survivors of violence: from Allende supporters in Chile, tortured by Pinochet’s dictatorship; to Christian missionaries raped as a punishment for speaking up against genocide in Guatemala.

The documentary exposed the aims of US foreign policy in these countries, with the deliberate intention being to crush any Latin American workers and poor who would aspire towards a better life; punishing the masses so severely they would never aspire to ‘rise up’ (or indeed, vote for a politician that might represent their interests) again.

His analysis was uncompromising. “Why did America attack these tiny countries?” he asked. “Because the weaker they are, the greater the threat. People who can free themselves against all the odds, will surely inspire others.”

“Both sides”

In recent months, the faux-impartiality of journalism has been further exposed over the question of Palestine. As Pilger himself explained:

“In Britain, much of television journalism is devoted to a mythology of ‘objectivity’, ‘impartiality’, ‘balance’. The BBC has long elevated this to a self-serving noble cause, allowing it to broadcast received establishment wisdom dressed as news.”

Faced with an obvious injustice, the truth is not represented by allowing ‘both sides’, as though they were equally valid. A principled journalist must squarely point out who is the oppressor, and who is the oppressed.

In his documentary, Palestine is Still the Issue (2003), filmed in the middle of the Second Palestinian Intifada, Pilger traced the contours of the conflict: from 1948, through the Six Day War, the First Intifada, and the “classic imperialist stitch up” of the Oslo accords in 1991.

His documentary revealed the harshness of the Israeli occupation and the everyday humiliation of the Palestinian people, explaining how this paved the way for the Second Intifada. This was characterised largely by desperation, including the emergence of suicide bombing as a tactic.

Never one to shy away from the controversial questions, Pilger picked apart the myth of the “crazy suicide bomber”, finding the real root cause of these attacks in the poisoned soil of occupation and abject misery.

Interviewing both the parents of the victims of the suicide attacks, and the family members of suicide bombers, Pilger’s interviewees all blamed the illegal occupation, and its sponsors in the West, for driving Palestinian youth to despair, and in turn to terrorism.

Of course, this invited retribution. Pilger, like so many other pro-Palestinian voices, was called a terrorist sympathiser, overly partisan, and a dangerous propagandist in reviews of his film. Such is the price of telling the truth.

Establishment revenge

Pilger produced many documentaries during the so-called ‘War on Terror’. In these films, he would always seek to trace terrorism back to its origins, resisting media sensationalism, even when propaganda was at its peak post 9/11.

In 2003, he produced a documentary entitled Breaking the Silence: Truth and Lies in the War on Terror. In it, he correctly asserted that mainstream media outlets and journalists were complicit in the deaths caused by the Iraq war, by refusing to expose the lies of US president George W. Bush and UK prime minister Tony Blair.

Around this time, we struck up a correspondence with Pilger, publishing one of his articles on our website in 2005, with his permission.

PIlger did indeed come under pressure, even from the very beginning of his career, for his forthright opinions and exacting investigations.

The Thatcher government, for example, surveilled his reporting in Cambodia/Vietnam. In the early 1980s, the UK foreign minister allegedly compiled a charge sheet on Pilger, and was hunting for a ‘hired gun’ journalist to carry out a “hatchet job” on him: so desperate were the establishment to discredit this persistent thorn in their side.

Nevertheless, Pilger garnered immense respect from his peers. He won multiple awards for his dispatches from Vietnam and his documentary on Cambodia.

But he also attracted many hit pieces throughout his life – and after death. He came under renewed, vicious opposition after scrutinising official narratives concerning the Bosnian War, Syrian Civil War, the persecution of Julian Assange, and the run up to the war in Ukraine.

For daring to express these dissenting opinions, he was ostracised from mainstream journalism towards the end of his life, meaning he increasingly relied on his personal blog. In the hallowed institution of the ‘free press’, it seems only the agreed capitalist line is permissible.

His obituary in The Telegraph described him as a “genocide apologist”, “indifferent to human suffering and human rights abuses”. The Telegraph would, of course, know something about genocide apologism, given their recent coverage of the Israeli war in Gaza.

These slanders could not be further from the reality. Pilger unearthed thousands of hidden truths about genocides, human rights abuses, and coups that would otherwise have remained hidden. And he delivered these revelations to as many people as would watch, packaged in the form of excellent documentaries, TV shows, and articles.

His interviews with the victims of capitalism and imperialism across the world were always compassionate, showing a deep humanity. And his outrage at the perpetrators of these crimes, and those who would keep them covered up, always came through clearly.

His tireless reporting left behind an archive of 60 documentaries, which are free to access on his website, offering a wealth of information about the crimes of imperialism. These should be watched as widely as possible.

Described by colleagues and friends as an “unrepentant socialist”, the communists of the IMT recognise Pilger’s steadfast refusal to bend to establishment bullying and slanders in pursuit of the facts.

He was a genuine journalist, a rare thing in this day and age, committed to shining a penetrating light on the sordid crimes of capitalist imperialism. This great legacy dwarfs the paid propagandists today penning bile against him.