With Italian politics in turmoil, we publish here a recent article by Roberto Sarti of the Italian Marxists “Falce Martello” who explains the economic, social, and political background to this current turbulent period of crisis. Although written before the recent rebellion against Silvio Berculoni by MPs in his own party and the latest vote in favour of the ruling “grand coalition”, the article provides a thorough analysis of the deep instability that exists within Italian politics due to the ongoing economic crisis and its social impacts.

With Italian politics in turmoil, we publish here a recent article by Roberto Sarti of the Italian Marxists “Falce Martello” who explains the economic, social, and political background to this current turbulent period of crisis. Although written before the recent rebellion against Silvio Berculoni by MPs in his own party and the latest vote in favour of the ruling “grand coalition”, the article provides a thorough analysis of the deep instability that exists within Italian politics due to the ongoing economic crisis and its social impacts.

The salvage operation of the Costa Concordia cruise ship caught the attention of the world media last week and the Italian ruling class immediately tried to cash in, with Prime Minister, Enrico Letta, stating, “If we succeeded with the Costa Concordia, we can do it with the Italian economy”! The recovery of the Italian economy, however, is a far more daunting and difficult operation and there are no signs that it is going to happen any time soon.

The propaganda of the government and of the bourgeois media could not be further from the real life of ordinary Italian workers. The latest figures, in fact, show that Italian Gross Domestic Product will fall by a further 1.8 percent this year. After five years of crisis, there is still no sign of the famous “light at the end of the tunnel”.

Unemployment is rising. In the last three years, one million people between the age of 25 and 34 have lost their jobs. Under the age 35 only four out of ten people are working. Officially, there are over three million unemployed in total, but many people have given up on looking for a job because they have no confidence that they are going to find one. In 2012, more than 9 million people were classed as poor, of which 4.4 millions living in absolute poverty conditions.

A recent survey carried out by Legacoop (a big supermarket chain) confirms in writing what has been obvious for some time: three million households, 12.3 percent of the population, cannot afford a high-protein meal every two days, 9 million Italians would not be able to meet an unexpected expenditure of €800, Italians are giving up more and more the use of a car (25 per cent of the population), they no longer go on holiday (4 million fewer people this summer), and they don’t buy new clothes (23 per cent of the population).

Spending on food in the past six years has fallen by 14 %, falling to the levels of 1971 (€2,400 per capita). The forecasts for 2014 are that there will be a further declines of -0.5 per cent in food and -6.1 in non-food spending.

After coming back from the summer “holidays”, the government decided to abolish the IMU tax for everybody. The IMU is a municipal tax on home owners, (the equivalent to the Council Tax in the UK). In Italy more than 75% of households own the home where they live. This is because rents are scandalously high). The point is that the tax was removed also for the rich who live in mansions and luxury flats. It will be replaced by a “service tax”, paid for by everyone, even low income families that do not own any property and live in rented accommodation. It will be another heavy burden for the poor. Obeying the diktats of the EU Commission, the Letta government is also preparing the wholesale privatization of the public sector and another cut in public spending by the end of the year.

In the meantime the bourgeoisie has never had it so good. The number of super-millionaires, that is Italians with a net worth of more than $30 million (€23 million), has grown by 7% in the past year, passing the 2,000 mark to reach 2,075. This tiny minority of Italians have a jaw-dropping $235 billion (€178 billion) income, an average of €86 million each.

The social situation is rotten to the core and the class divide has never been so deep since the 1950s and the already deep political rifts between rulers and ruled has become an unbridgeable chasm.

As opposed to what we saw in Greece, Portugal or Spain, in Italy the political crisis erupted before a social explosion. Since November 2011 the ruling class has had no other option but to rule through a government of national unity. The political election of February 24-25 produced a stalemate situation, with no single force able to get a majority in both the Parliament and the Senate. The rise of the Five Stars Movement (M5S), from nothing to 25% of the electorate reflected, although in a distorted manner, the seething anger and discontent amongst the Italian workers and youth (see Italy: A crisis of the system – an assessment of the elections of February 24/25). Like so many other countries Italy was left with a hung parliament.

Such was the impasse that it took two months before some agreement could be reached over a coalition government. How deep the political crisis was can be seen from the inability of the Parliament and Senate to come to an agreement during the election of the President of the Republic. The President in Italy holds office for seven years. In April President Napolitano had reached the end of his term, but the only agreement all the main parities could reach was to ask him to stay for a second term, an unprecedented situation in the history of post-war Italy. Napolitano, in spite of his old age – he is 87 – accepted. This event in itself is an indication of the deep political crisis.

However, what is even more striking is the role Napolitano has been playing. In the past the President would call on the leader of the party, or coalition of parties that had won a majority, or at least has a sufficiently large number of MPs, to form a government, and that would be more or less the end of his role. Not this time! Napolitano, after being re-elected, dictated to all the major parties what they must do. He was the direct voice of international finance capital telling the Italian parliament what it had to do: form a government of national unity and get on with the serious business of sorting out Italy huge public debt!

What is even more worthy of note is that Napolitano was once a major leader of the old Italian Communist Party, PCI, albeit one of its most right-wing leaders. The irony of history was to see this so-called “Communist” saving the day for the Italian bourgeoisie, becoming the real “guarantor” of the interest of the ruling class. This not unimportant detail graphically expresses how far the degeneration of the old Italian Communist Party had gone!

Thus at the end of April all the main parties came together to form a national unity coalition under the premiership of Enrico Letta, a politician who emanates from the right wing of the PD. This time it was not a government made up of “technocrats” with the external support of the main parties, as had been the case with Monti. The Letta government is a much more “political” administration, with ministers belonging both to the Democratic Party and the PdL (Berlusconi’s party), as well as Monti’s small party, Scelta Civica, and a few other minor independents.

In parliament, M5S, the SEL (Left Ecology and Freedom, Vendola’s party, the right-wing split from Rifondazione Comunista in 2009) and the Northern League are in opposition.

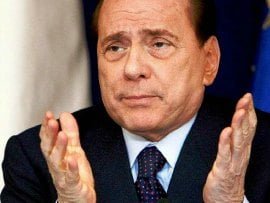

The Letta government has been weak from day one. Berlusconi agreed to this “adventure” because he hoped that by doing so, remaining somehow clinging to power, his legal problems would be solved. Berlusconi has faced many trials over the years, always managing to escape sentencing, in some cases thanks to laws that he himself as premier had managed to get on the statute books. This situation has created somewhat of an anomaly in the Italian political set up. It was Berlusconi, when in office at the head of a right-wing coalition, who abolished the previous Council Tax (ICI) in a demagogic manoeuvre to keep up his electoral support. This actually provoked serious financial difficulties to the local municipalities. Clearly what was good for Berlusconi was not good for the finances of the state. And Berlusconi was behind the recent decision to abolish the IMU tax. The man had become too much even for the Italian bourgeoisie, and particularly for international finance that is pressing for draconian cuts in spending and the imposition of new taxes.

In a certain sense, the chicken shave come home to roost for Berlusconi. Now too many sentences are hanging over his head and his political and judicial fate is clearly doomed. This, however, poses a problem. Berlusconi is leader of one of the two major parties that support the present government. If he decides to withdraw support the government would fall, throwing Italy into even deeper political chaos and instability.

Since at present there is no alternative to the present coalition, the ruling class is trying by all means to keep this government alive. When Berlusconi raised his voice, threatening a government crisis some weeks ago, the bourgeoisie gave him a clear warning. Mediaset (Berlusconi’s main company) stocks fell by 6.2% in just one day. “Il Cavaliere” [The Knight, as he is often referred to] lost €150 million in just four hours! Last week Italy was kept waiting for yet another of Berlsuconi’s videoed speeches. When it was finally broadcast, you could see a tired man, his face covered with wax to hide the devastating effects of decades of plastic surgery. The physical image of the man eloquently matches that of the end of an era. The problem for the capitalists is that they do not know how to deal with the new era that is opening up in front of them.

The ruling class prefers to hold on to this government than to move towards another general election. The latest figures show that Italy annual budget deficit has gone over the 3% ratio to GDP, as established by the EU, a worrying sign for the bourgeoisie. The pressure is on to introduce even more cuts very soon. The fact that the local Council Tax has been abolished, at least for this year, means they must urgently find the money elsewhere.

The problem they face is that the opinion polls indicate that the results of an election today could be more or less the the same as in February of this year, producing yet another hung parliament. Thus not only would they lose precious time in calling the elections, holding the election campaign, and then spending time on negotiating yet another coalition government, ending up with more or less the same as the one they have now.

The dilemma of the Italian bourgeoisie – one that they have had for some time – is more than ever an insoluble one: the ruling class no longer has effective tools with which to govern the country. Monti’s small party is in disarray and divided into many factions, after receiving only 8% of the votes in the last elections, and all the opinion polls indicate it would get between 4-5%.

The Italian capitalists are like a person travelling in a vehicle in which the controls are no longer responding to the driver. At the first bend the vehicle will end up swerving off the road, and this could happen at any time: a parliamentary incident, or an international crisis in the financial markets, or an outburst of the class struggle. All these, and other incidents, can shatter the precarious balance of this government, leaving the bourgeoisie sitting on a pile of rubble.

The fact of the matter is that every single party of the political spectrum in Italy is unstable and in crisis. “New” parties and electoral coalitions spring up like mushrooms and die within the space of a season. It is a sign of the extreme weakness of the Italian bourgeoisie.

No wonder that the main concern of this ruling class is to keep “the social peace” at all costs. In this endeavour the leaders of the trade unions are proving to be reliable allies. The leader of the CGIL (the traditional left union, with close ties to the PD) Susanna Camusso, has transformed the word “governability” into a beacon for every action of the trade unions. In an agreement signed between the Confindustria, the bosses’ confederation, and the three main unions (CGIL, CISL and UIL) at the beginning of September we are told that, “Governability is a value that has to be defended because it means conditions for stability for restarting a positive cycle of our society.”

Who forms the government and which class interests it is defending are unimportant questions for these “leaders” of the working class. And there is no talk of what a union should do in the middle of a crisis: a general strike, a demonstration, mass mobilisations to defend jobs and wages, and so on. Nothing has been organized by the three main trade union confederations for this autumn. Nothing has even been done to put pressure on the Democratic Party that, in the last analysis, is the main point of reference for the union leaders. Why? Their policy is one that we have seen many times in the history of the workers’ movement: it is called class collaboration. In the ruling class’s moment of need all these union leaders can think of is how to hold back the movement that is ready to explode from below!

The Democratic Party (PD) is holding its congress in the next few months, between November and December. The PD was the real loser of the last elections, winning far few votes than they had been expecting and as a result the party secretary, Bersani, was forced to resign. This means a new secretary must be elected and this has brought out clearly the internal divisions within this party. Matteo Renzi will probably emerge as the winner.

Renzi is presently the Mayor of Florence, and a champion of privatization of the council’s assets. He comes from a Christian Democrat background, with no relation at all with the former Communist Party apparatus. In the previous election of party leaders Renzi was defeated by Bersani. This is because Renzi was seen as the more openly bourgeois of the party leaders and Bersani had at least some connection to the historical tradition of the old Communist Party.

Renzi is the favourite candidate of the bourgeoisie that is financing him heavily. At the same time, the rank and file of the party now acclaim him, as they see him as the only one who can win the election and get the party out of the impasse it is in. It is a party that has been stunned by the alliance with the “arch-enemy” of the past, Berlusconi, something they would never have imagined possible in the past. Thousands of people cheered him at every meeting organised at the PD festival this summer. The candidate of the “apparatus” of the former Communist Party, closer to the CGIL, Cuperlo (the last secretary of the FGCI, Young Communist League, in the late eighties before the dissolution of the old Communist Party) has little chance of defeating him.

Renzi in fact has adopted anti-Berlusconi rhetoric for tactical reasons, but his victory will not solve the contradictions within the party, on the contrary it is going to exacerbate them. The wing around Bersani will not leave the party to Renzi without putting up a fight. The clash at the national assembly of the PD, celebrated last week, where the rival factions were unable to reach an agreement even on the rules for the forthcoming congress, says a lot about the internal conflicts that we will see in the PD in the near future.

In Italy we have witnessed a peculiar phenomenon. Due to its historical weakness the Italian bourgeoisie has never been able to create a party which directly represented its interests. Even the Christian Democracy was no such party and proof of that was it ignominious collapse in the early 1990s after it was engulfed with the exposure of such levels of corruption that it lost the bulk of its support. Berlusconi stepped in to replace the old Christian Democracy, but he too has proven to be a party not of the bourgeois as a whole, but only of a particular wing, the more backward wing to boot.

Thus, after the old Communist Party in 1991 transformed itself into the PDS (Party of the Democratic Left), and later the DS (Democratic Left) the bourgeoisie endeavoured to create this long desired for party through the dissolution of the DS and its fusion with a series of smaller bourgeois parties. That is how the PD came into being. At the same time, the failure of the second Prodi government in 2008 (a coalition government of the so-called centre-left) led to a collapse of the parties to the left of the Democratic Party, which were all excluded from the parliament. This included Rifondazione Comunista, which paid a very heavy price for its participation in the Prodi government, losing all its MPs and Senators.

The working masses were left without an alternative, so, while a sizeable sector decided to abstain (and later many voted for the M5S), another significant layer remained loyal to the Democratic Party. Herein we have a peculiar contradiction with a bourgeois party that is the point of reference for a significant part of the left oriented masses and for the trade union apparatus of the former (and main) “communist” union, the CGIL. However, this contradiction cannot last forever. In the recent period, these contradictions did not emerge openly thanks to a temporary lull in the class struggle and the formation of the various national unity coalition governments. This situation cannot last much longer and the class tensions that are inevitably going to explode with Italian society, are going to also express themselves within the Democratic Party itself.

One of the reasons for this is that the vacuum within on left is greater than ever before. The Left Ecology and Freedom (SEL) party was able to get into parliament because it entered into an electoral alliance with the PD. When the PD agreed to enter the Letta government the SEL found itself in opposition, but they desperately want to rebuild a new alliance with the Democratic Party, and are looking to Renzi with big hopes.

The left leaders and intellectuals are all affected by a virus: the virus of unity at all costs. Of course, we advocate unity, but a genuine one based on class interests. Any unity without a common class programme, strategy and goals, only lead to disaster, as proven by the calamitous results of the various electoral fronts promoted by Rifondazione Comunista (PRC), the “Rainbow Left” in 2008 and “Civil Revolution” in 2013.

In every appeal for the “reunification of the left” they seek the lowest common denominator, which lasts for a season, if they are lucky. The latest of these gimmicks is an appeal to defend and apply the Italian Constitution. This constitution was drawn up in 1948 as a by-product of the defeated revolution of 1943-45, and therefore it contains many verbal concessions to the left but, of course, it was never put into practice. In recent years it has been emptied of any progressive content, for example by introducing an article which obliges all governments to have “balanced budgets”. It is a rearguard battle, which has no appeal to the masses of workers and youth, but all the leaders of the left are supporting it, and have organised a national demonstration on this question for October, 12. One of the promoters of this campaign is Landini, the popular leader of the FIOM, the militant metalworkers’ union affiliated to the CGIL. He thus provides a left version of class collaboration, resurrecting petty bourgeois intellectuals worthy of standing in some wax museum, instead of organizing the real and much needed class struggle.

The leaders of Rifondazione Comunista are of course amongst the supporters of this appeal. Rifondazione Comunista is holding its congress at the beginning of December. It is a party ravaged by several electoral defeats, with no money, no strategy and with an alarming decline in membership. According to some calculations, in 2007 the party had more than 87,000 members, and in 2008 71,000, not to mention the more than 100,000 members it had in the years after the party was founded in 1991 when the old Communist Party split. By the end of 2012 the membership had fallen to 31,000. There is a de facto liquidation of the party taking place, with very few branches meeting regularly, and in which the internal debate is very poor.

The PRC is no longer the decisive point of reference for trade union and left activists. Our proposal, as the Marxist wing of the party, at the next congress will start out from these concrete facts. While arguing for the need of a party of the working class, in our motion to be presented in every branch of the PRC, we are going to put into practice this demand, agitating for it with our revolutionary programme in front of the factories, workplaces, schools and universities, as we discussed in our successful national assembly, Sinistra, classe, rivoluzione (The Left, the working class and the revolution) held in Bologna last July. It will be clearly a “them (the leadership) or us” struggle, as we explained, not because it is a question of prestige, but because what it is at stake is the very future of the communist movement in this country.

We state clearly what we need today: the building of a political force, a party of the working class and oppressed sectors of society, a party that breaks with this atmosphere of national unity and class collaboration, and raises the flag of the class struggle and the fight against the system. This party will be forged by events, and not by the voluntary act of small group and tendencies, but we want to be in the frontline of this process.

The split at the top in society and the impasse facing the bourgeoisie is an indication of revolutionary ferment below, as the Marxists have often explained. A reflection of the big splits that exist within the ruling class has been the readmission of the FIOM shop stewards into the FIAT plants up and down the country. Marchionne (FIAT CEO) expelled the FIOM from the FIAT factories between 2010 and 2011 after the FIOM refused to sign a rotten deal. Now, however, he has had to abide by a decision of the Supreme Court in favour of the shop stewards. This was a victory for the workers and for the union activists and it is mainly the product of their determination stance. The concerns of a major wing of the bourgeoisie, which controls the judiciary, played a role in this. They fear – and rightly so – that when the Italian workers rise again in militant struggle, there will be no buffer (i.e. the trade union bureaucracy) between the anger of the proletariat and the propertied class of exploiters.

We share this very same perspective with the masters of the capital, but from the opposed class point of view. The tension building up among ordinary working people is tangible everywhere. There is real pain and suffering, with growing poverty and an ever growing sense of injustice. People feel they can no longer go on living like this. This tension is about to break in the form of unprecedented class struggle. The difference is that while the bourgeois, the PD leaders and the trade union bureaucracy are working to direct this tension into safe channels, we are working to organize this anger of the working class and youth, to break the social truce, to give it a programme and a strategy to overthrow the capitalist system.