Steve Jones examines the Poliziottesco genre of Italian cinema, an all but forgotten period of film, which provides a vivid portrayl of the corruption, crime, and political scandal that gripped Italy in the 1970s.

Steve Jones examines the Poliziottesco genre of Italian cinema, which provides a vivid portrayl of the corruption, crime, and political scandal that gripped Italy in the 1970s.

At its height, in the 1960s and 70s, the Italian film industry was producing over three hundred films a year, maybe more. These were not just the familiar award-winning art films of Visconti, Fellini and others, but also included a huge volume of cheaply-made films targeted towards a popular worldwide market.

These films normally fed off successful US titles and genres with a view to quickly capitalising on their popularity – sometimes even before the big-budget original had come out. So we had the “Spaghetti” Western genre (Sergio Leone, etc.), the horror genre (Mario Bava, Lucio Fulci), the murder-mystery or Giallo genre (Dario Argento), and even a bizarre euro-spy genre featuring an assortment of James Bond clones.

All but forgotten

Any big film hitting the cinema screens would be quickly – and cheaply – copied (often with minimal changes to story and characters), and these films, if they did well, would in turn also be copied and re-copied, often with the same actors popping up time and time again. This would happen even with original Italian films if they were successful enough, hence the sword and sandal “epics” which came out in the early 1960s, with the likes of Steve Reeves playing endless Hercules variations. Pasolini’s 1971 film ll Decameron/The Decameron, for example, generated a spate of Italian-made medieval comedies within a year or so, all with the word Decameron in the title somewhere, ready to be shipped off round the world.

So many films were being made in Italy during this period with a wider market in mind that there was a fulltime unit operating in Rome with the sole task of just dubbing these films into English. All these genres have now achieved some sort of cult status and the best of these films are revered by critics and audiences alike.

However, until recently, one such genre, the Italian police-crime film (or Poliziottesco as it is often called) despite generating nearly 300 films over just ten years, had all but been forgotten, almost deliberately it seemed.

In 2004, this started to change when the Venice Film Festival began to feature a regular spot in its programme of events called ‘The secret history of the Italian cinema’. These retrospectives were to include not only Westerns, gialli, etc., but examples of the Poliziottesco (plural Poliziotteschi) genre as well. With support from filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, these lost films have started to see the light of day again.

Corruption and crime

Drawing on the international success of US films like Dirty Harry, The French Connection, The Godfather, and later on Serpico and Death Wish, the Poliziottesco genre would, almost uniquely, be ‘…a completely contemporary popular genre… many of its plots and its most popular themes could have easily been lifted from the pages of the cronaca nera (crime news) of any urban newspaper from the 1960s to the early 1980s, a period of great social, economic and political unrest in Italy.’ (Bondanella, A history of Italian Cinema, 2009)

What Bondanella is referring to in his book is that period in recent Italian history often called The Years Of Lead (Anni di piombo). The 1970s in Italy was seen as a time of extreme violence, street crime, shootings, bombings and assassinations, corruption and cover-ups involving not only organised crime but also political groups and the state machine itself.

Over 2,000 lives were lost during this period. At one point, rich people took to hiding their wealth when travelling around for fear of robbery or kidnapping. If they wanted to party they would sometimes relocate to a city like Paris where they felt safer. The growing economic divide between rich and poor was becoming more obvious and all manner of fissures were starting to be revealed within society… and within Poliziottesco.

Some of these Poliziotteschi films even reference the strong belief of many at the time that the state, big business and the CIA were about to engineer a fascist coup to stop the left (i.e. the Communists) coming to power – it was said that the government was operating during this time under a “strategy of tension”. In 2000, it was confirmed that the CIA had indeed been working on such plans had the right-wing Christian-Democrats been under real threat of being booted out.

All of these themes would feature routinely in many, if not most, Poliziotteschi films in one way or another. These films were not shot in the usual tourist spots in Italy but in the industrial wastelands and poor areas of Rome, Milan, Naples and elsewhere and would end up reflecting the economic conditions of the day far more than many mainstream films did.

Violence of the time

At this point it should be made clear that these films are not Citizen Kane by any means, but were intended for a popular, mainly male, mass market. They were cheaply made, look very dated now and were extremely violent for their time. Health and safety were not words that had any meanings on these sets – how no-one was killed in the making of these films remains one of life’s mysteries. Action sequences were often just shot, quickly and without permission in the hope that they would be finished and the crew gone before the authorities arrived demanding bribes. The reason many people looking on in crowd scenes in these films are astonished is simple – they usually had no idea that what they were seeing was not really happening!

These films also had a particularly bad attitude towards women (who were almost always cast as prostitutes, strippers etc.), even compared to the frankly dismal standards of 1970s cinema as a whole and Italian cinema in particular. Virtually no women ever had leading roles in these films and many refused to appear in them. Even familiar actresses such as Rosalba Neri and Edwige Fenech who featured in just about every exploitation film going during this period were largely absent from Poliziottesco, clearly by choice.

Eurocrime! The Italian Cop and Gangster Films That Ruled the ’70s (Mike Malloy, 2012) is the first major documentary to deal with Poliziottesco. A large number of the key actors and crew members involved in the making of 1970s Poliziotteschi films get to be interviewed and are able to provide some sort of overall picture. All the issues discussed above are dealt with in detail during the documentary with the exception of the political angle – apart from a mention about the activities of the Red Brigade, who were active then and provided some of the themes used by filmmakers. This is a pity, as it is the most interesting aspect of the genre and the one that explains why, from the 1980s onward, it was buried by an embarrassed cinema establishment.

Masterpiece

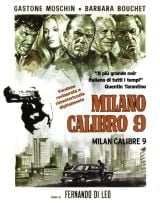

The genre’s one true masterpiece is Fernando Di Leo’s Milano Calibro 9/Caliber 9 (1972) which is now finally available on disc in the UK from Arrow Films. The story is straightforward enough. A small time crook, Ugo Piazza (Gastone Moschin, playing brilliantly against type), is released from prison after serving a short sentence. However, both police and the local criminals suspect him of having been behind the stealing of a now-missing large bundle of the mobs’ money… and the mafia want it back. In this film crime clearly does not pay – all the mafia men seem to live in shabby flats and even the main mafia boss, the Americano, operates out of a faceless and drab office block. They bemoan their lot and simply cannot understand why things have turned out so bad. Only the bankers and wealthy industrialists seem to be doing OK.

The genre’s one true masterpiece is Fernando Di Leo’s Milano Calibro 9/Caliber 9 (1972) which is now finally available on disc in the UK from Arrow Films. The story is straightforward enough. A small time crook, Ugo Piazza (Gastone Moschin, playing brilliantly against type), is released from prison after serving a short sentence. However, both police and the local criminals suspect him of having been behind the stealing of a now-missing large bundle of the mobs’ money… and the mafia want it back. In this film crime clearly does not pay – all the mafia men seem to live in shabby flats and even the main mafia boss, the Americano, operates out of a faceless and drab office block. They bemoan their lot and simply cannot understand why things have turned out so bad. Only the bankers and wealthy industrialists seem to be doing OK.

A running commentary in the film is provided by two policemen also investigating the stolen money – one left-wing, one right-wing. Early on the left-wing cop complains that the real villains are the rich bosses who fiddle their taxes and hides money away. He also seeks to defend the students and the poor, who audiences would have known were regular targets of the police and the state.

Later on, the right-wing cop jokes that he had arrested one northerner who wasn’t a student – a reference to the belief that all those from the south of Italy were potential criminals. Such references, which would have made little sense to those outside Italy, explains why these films often did not do as well beyond the home market as the producers might have hoped. In subject they were simply not international enough.

This was despite applying the standard Italian practice of employing available American actors to give the films an international look. The Poliziottesco genre would see US actors like Henry Silva, Martin Balsam, Woody Strode, John Saxon and Richard Conte travel to Italy to join up with home-grown actors like Luc Merenda, Tomas Milian and Franco Nero. The financial problems which hit Hollywood, which was no longer immune from the changing state of the world economy by the 1970s, meant that many American actors were now more than ready to grab any work going, even if it meant going to Europe. Of course, the actor they really wanted back was Charles Bronson, but no-one in Italy could afford him anymore, so they brought forward Maurizio Merli who looked like both Bronson and Nero and in this guise would feature in a large number of these films, usually as a maverick policeman. In this context, Milano Calibro 9 also features token American Lionel Stander as the mob boss.

Marx and cinema

Fernando Di LeoDirector Fernando Di Leo (1932-2003), it is said, came from a Communist background and in one interview quotes from Karl Marx, adding “Too bad Marx had nothing to say about cinema.” Di Leo would also state that he wished to show how poverty, corruption and organised crime degraded the working class.

Fernando Di LeoDirector Fernando Di Leo (1932-2003), it is said, came from a Communist background and in one interview quotes from Karl Marx, adding “Too bad Marx had nothing to say about cinema.” Di Leo would also state that he wished to show how poverty, corruption and organised crime degraded the working class.

The political undercurrents evident in Milano Calibro 9 are also picked up in later films of his. In Il boss/The Boss (1973), for example, scenes are shot outside the real headquarters of the Christian-Democrats, real politicians names are mentioned and the never-seen big crime boss, a politician in Rome, is only ever called “His Excellency.” Draw your own conclusion. One real senior politician was so enraged by the film that he threatened to sue the producers for defamation until it was pointed out that he wasn’t actually ever named in the film and if he went ahead with the action people would want to know what was in his bank account! He hurriedly retreated.

Il Boss presents a pessimistic vision in which everybody – criminal and cop alike – is corrupt and ready to double-cross at the drop of a hat. Not all of Di Leo’s films would be as political as say Il Boss, but most of them would have something interesting to say. Even Colpo in canna/Loaded Guns (1973), which on the face of it is simply a lightweight caper film from Di Leo with elements of comedy mixed in, is notable in that the film unusually centres on a strong role for a woman. The character played by Ursula Andress manages to outwit and run rings round the rest of the male cast, who all come across as clueless compared to her.

The menace of fascism

Any event in the news would be picked up by the filmmakers and used as a subject for a possible production. For example, Perché si uccide un magistrato/How to kill a judge (1975) was based on the murder of magistrate Pietro Scaglione by the mafia after he had started looking into the murder of trade unionists. La polizia ha le mani legate/Killer Cop (1975) picks up on the fascist bombings which were taking place at the time and suggests a fifth column working inside the Milan police force itself.

The potential rise of fascism in 70s Italy is also looked at in La polizia interviene: ordine di uccidere!/The left hand of the law (1975), which is more political drama than police thriller it must be said. Fascist groups based around rich students on campus would serve as a theme for several films following the 1975 scandal when two girls were held captive and brutally treated by upper-class youths. I ragazzi della Roma violente/The children of violent Rome (1976) was just the first such film to draw on this event.

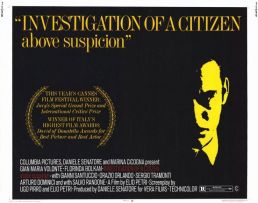

There is an argument for saying that the Poliziottesco genre owes much to Elio Petri’s Oscar-winning 1970 film Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto/ Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion. Here we again see a typical crime film plot – a cop investigating a murder which it turns out he had committed himself – being used as a commentary on what was happening in Italian society. The policeman (Gian Maria Volonté) has just got a job in the political division and demands action against strikers, anarchists, etc. seeing them as the same as robbers and prostitutes. He is so confident of his own position that he deliberately plants evidence against himself to see how far the other officers will go in ignoring these clues. At the end, he dreams (or maybe not) that the heads of the police force arrives at his home to confront him about the murder before letting him off with a mild warning not to do it again. The Italian police authorities were so wound up about the film that they turned up in numbers to the premiere and were clearly looking to take action against it. However, in the end there was little they could do and the film went on to enjoy considerable home and international success.

A picture of society in crisis

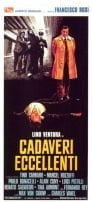

Mainstream cinema largely ignored Poliziottesco, with the honourable exception of Francesco Rosi’s Cadaveri Excellenti/Illustrious Corpses (1976), which is still not available on disc in the UK. This film takes a familiar theme within crime stories– the investigation of a series of possibly linked murders, in this case a group of judges – and uses it to expose the corruption and decay within Italian politics. The investigating officer (Lino Ventura, joining a heavyweight cast including Fernando Rey and Max Von Sydow) thinks at first that the murders are being carried out by a man wrongly found guilty by the judges at some point in the past and lists a series of suspects for investigation, the most likely of which has now just disappeared. High-up politicians, however, force him to abandon this line of approach and instead link up with the political police who are cracking down on students and radicals, blaming them for the murders. Increasingly the cop comes to suspect that the political elite know more than they are letting on. At one point, he visits late at night a judge he thinks may be next on the hit list; on leaving he hears dance music and voices coming out of another flat in the building and walks in to find a bourgeois dinner party going on, with all the politicians and police chiefs present, along with one of the radical leaders he was supposed to be investigating. The original book on which the film was partially based was set in an unnamed country, but Rosi felt it was important to have the film take place in Italy so that the message would be completely clear. He considered it to be his most political film.

Mainstream cinema largely ignored Poliziottesco, with the honourable exception of Francesco Rosi’s Cadaveri Excellenti/Illustrious Corpses (1976), which is still not available on disc in the UK. This film takes a familiar theme within crime stories– the investigation of a series of possibly linked murders, in this case a group of judges – and uses it to expose the corruption and decay within Italian politics. The investigating officer (Lino Ventura, joining a heavyweight cast including Fernando Rey and Max Von Sydow) thinks at first that the murders are being carried out by a man wrongly found guilty by the judges at some point in the past and lists a series of suspects for investigation, the most likely of which has now just disappeared. High-up politicians, however, force him to abandon this line of approach and instead link up with the political police who are cracking down on students and radicals, blaming them for the murders. Increasingly the cop comes to suspect that the political elite know more than they are letting on. At one point, he visits late at night a judge he thinks may be next on the hit list; on leaving he hears dance music and voices coming out of another flat in the building and walks in to find a bourgeois dinner party going on, with all the politicians and police chiefs present, along with one of the radical leaders he was supposed to be investigating. The original book on which the film was partially based was set in an unnamed country, but Rosi felt it was important to have the film take place in Italy so that the message would be completely clear. He considered it to be his most political film.

After about ten years of success, at least in Italy anyway, the genre succumbed to the usual fate of all Italian cult genres: a grim descent into parody, sentimentality and dismal humour together with the usual cost-cutting efforts and the money-saving recycling of whole scenes from earlier films, something that the Eurocrime! documentary draws out well.

By the 1980s the genre was all but dead as the Italian film industry itself went into a tailspin, thanks to the rise of competition from new TV channels, from which it never really recovered. The best films of the Poliziottesco genre serve now to provide us with an oblique picture of a society in crisis and for that reason alone deserve further study.

Hopefully the release of Eurocrime! and Di Leo’s Milano Calibro 9 in the UK will be just the start.

Further reading and discography

Whereas the bookshelves of most large bookshops are heaving with books about Italian Westerns, and even titles dealing with the giallo (named after the colour of crime paperbacks in Italy) genre can now be found, there is little literature in English available on Poliziottesco. However, Italian Crime Filmography 1968-1980 (Roberto Curti, 2013) is an important (actually the only) English-language reference book on the subject – copies can still be found on Amazon. Also worth picking up is the above mentioned A History of Italian Cinema (Peter Bondanella, 2009 edition), which unlike most other books on Italian cinema does give fair weight to the mass-market output and contains a concise analysis of Poliziottesco. Video Watchdog Issue 177 (USA, 2014) contains two detailed and most useful articles dealing with the genre and reviews a number of key DVDs.

So far as to the availability of Poliziottesco on DVD and Blu Ray, things have started to improve. A large number of these films were bought up on the cheap by video companies in the 1980s and released in rental shops in the UK and US. These tapes have since served as sources to be used as cheap-and-cheerful bargain bin product by firms taking advantage of the fact that in the US many of these releases have slipped out of copyright and are now declared to be Public Domain films. Often these box sets, although very cheap, suffer from dismal print quality. However the Pop Flix sets – Mafia Kingpin, Crime Boss, and Big Guns – are worth hunting down as the quality is a bit better than usual for PD boxsets and they represent the only way at present to see films like Emergency Squad, Violent Naples, Confessions of a police captain, Big Guns and others, albeit in US dubbed prints. These films are all region free.

In the UK, Shameless have released the very violent and pessimistic Milano odia: la polizia non pu sparare/ Almost Human and the more recent and even more violent Contraband, Lucio Fulci’s late and frankly rather poor entry into the genre. Arrow Films, in addition to Milano Calibro 9 has already released Si pu essere pi bastardi dell’ispettore Cliff?/ Super Bitch, which was shot partly in Britain and features well-known British comic actress Patricia Hayes as crime boss Mamma the Turk. To her credit she pulls this bizarre casting off and is clearly enjoying the role!

Outside the UK, Raro Video (a US/Italian setup) has issued two splendid Fernando Di Leo box sets containing Milano Calibro 9, La Mala Ordina/ The Italian Connection, Il Boss, and I padroni della citta/ Rulers of the City in volume one and I ragazzi del massacro/ Naked Violence, Il poliziotto e marcio/ Shoot First … Die Later and La citta sconvolta: Caccia spietata ai rapitori/ Kidnap Syndicate, in volume two. Some of these titles are also available separately. They have also released La polizia confitta /Stunt Squad, La Polizia ha le mon le gate/ Killer Cop, Uomini si nasce poliziotti si muore/Live like a cop, die like a man (which has an expected UK release later this year), Liberi armati pericolosi/Young, violent, dangerous, Pronto ad uccidere/Meet him and die, and Milano Rovente/Gang War in Milan. Blue Underground in the US did release a few titles some years ago of which Perché si uccide un magistrato/How to kill a judge, starring Franco Nero, can still be found.

In Italy a sizeable number of these films have come out on DVD, although most are not English friendly containing only Italian soundtracks with no English subtitle options. Exceptions are the Raro video/Nocturno releases Squadra Antiscippio/The cop in blue jeans and Colpo in canna/Loaded Guns. Raro Video/Minerva has also released Napoli… Serenata Calibro 9 with English subtitles, a film so sentimental and full of idiotic comedy that it has to be seen to be believed.

Investigation of a citizen above suspicion is available on an apparently top-notch Region A disc from Criterion (only playable on US machines alas), but is also available in an Italian release which is Region B and therefore playable on UK machines but note that only the main film contains English subtitles, the extras are all in Italian only. Hopefully it will not be too long before a UK company picks this film up for release.

A trawl round YouTube can locate a number of these films in various states of repair although a number are not in English friendly versions. The YouTube version of Investigation of a citizen above suspicion does present the opportunity to hear the rare English dub version.