8th March marks International Women’s Day, originally founded over a century ago by socialists to remember the struggles of working class women. Today, we are still a long way from achieving equality between the sexes in the workplace; and with the onset of the crisis in 2008 things have only gotten worse.

8th March marks International Women’s Day, originally founded over 100 years ago by socialists to remember the struggles of working class women. Working women have been struggling for complete equality in the workplace for over a century. We are still not there and with the onset of the crisis in 2008 things have got worse.

“Back in the 1990s women in rich countries seemed to be heading towards a golden era…Almost all rich countries have laws, passed mostly in the 1970s, that are meant to ensure equal pay for equal work, and the gap did narrow noticeably for a while when women first started to flood into the labour market.” [The Economist, November 2011].

In the United States the differential between women’s and men’s wages has been reduced from 40% to 20% since the 1970s. Significantly, most of this reduction came in the early years – i.e. on the back of the wave of class struggle in the 1970s – and since then the process has slowed down.

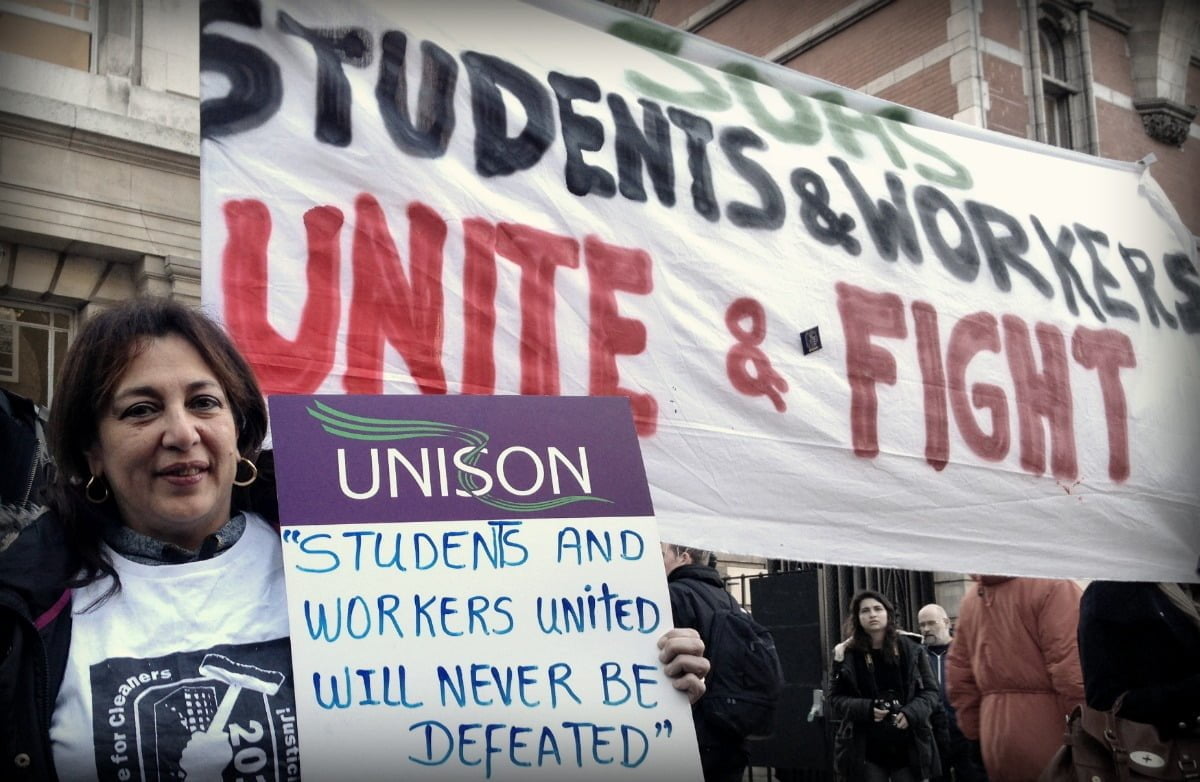

The rise in class struggle globally in the late 1960s and 1970s produced many reforms to the benefit of women and not only in terms of wages and conditions. Other basic rights, such as the right to abortion or divorce, were won in many countries where they had not been previously recognised. This shows that class struggle, a generalised movement of workers for better wages and working conditions, is enormously beneficial for women workers.

Struggles and crisis

In the 1980s the class struggle declined as a result of defeats on the trade union front. With these defeats came an onslaught on all the gains of the past, both on wages and democratic rights, affecting male and female workers. But women, and working class women in particular, were hurt the most.

The Economist admitted in its 2011 article that the 2008 crisis, “has thrown a spanner in the works”, a reference to the effects of the cuts in public spending, which were “beginning to hit female employment disproportionately hard.”

In Britain the impact of the crisis on wage differentials between working men and women has been dramatic. The World Economic Forum in 2014 revealed that Britain ranked out of 136 countries for gender wage equality, between 2006 and 2013, went from 9th to 18th, but in one year alone, from 2013 to 2014, it dropped even more sharply to 26th.

In 2014 the average wage for women in the workplace fell by £2,700. It was the first time ever that Britain has fallen out of the top 20 for gender wage equality. In fact, in 2014 average annual wages for women fell from £18,000 to £15,400, while for men the figure was stagnant at £24,800. Thus, the overall average annual wage differential increased from £6,800 to £9,400!

This big differential between female and male workers starts right at the beginning when young people enter the “labour market”.

Discrimination

According to a poll by the Young Women’s Trust [The Evening Standard, 7th September 2015], wages for male apprentices are 21 per cent higher than for their female equivalents. Young women earn on average £4.82 an hour compared to £5.85 for young men.

On an annual basis, young women are £2,000 worse off. The reason for this situation is the same for women of all ages, i.e. women tend to work more in low pay sectors, such as healthcare, childcare and retail.

Dr Carole Easton of the Trust explained: “It is staggering that in the 21st century, certain employment sectors are hardly welcoming any young women; less than two per cent of construction apprentices are female and less than four per cent of engineering apprentices. Women are funnelled very early into a narrow range of opportunities, that are stereotypically gendered.”

Dr Easton added that “Women’s concerns may also be different, perhaps needing flexibility to look after children or for other caring responsibilities.” This highlights another discrimination women suffer from, the unspoken rule that they cannot have a career in certain sectors because sooner or later most of them will have children. The capitalists would prefer not to have women who will at some point need to take time out of work, either to have children or later on to look after them. This channels women towards lower paid jobs.

Close to one quarter of the women interviewed complained about not receiving any other training outside of work. The equivalent figure for young men was only 12%. Young women are often employed to do work which requires very little training, condemning them to a life of low-wage jobs, i.e. legalised cheap labour.

Although they make up 47% of the overall workforce, women are not evenly spread across all types of employment.

Data from the Department for Education shows that in 2012 only two per cent of the early years workforce was male. Much childcare is provided by private nurseries that pay most of their staff the minimum wage. Women are also forced by family circumstances to take up low paid part-time jobs. While 2.11 million men are employed in part-time jobs, the number of women is 5.85 million.

Class conditions

The 2008 crisis has had a similar impact worldwide. According to an ILO report: “Globally, gender gaps in unemployment and employment trended towards convergence in the period 2002 to 2007,” but then, “grew again with the period of the crisis from 2008 to 2012 in many regions.”

The same does not apply to women who make it up the ladder, to the top of companies as CEOs, etc. In 2014 “there was a small increase in the percentage of women in senior official and managerial positions up from 34% to 35%…” [The Independent, 28 October 2014].

Women’s living conditions are determined by the class they belong to, only the situation is far worse for them. As in the 1970s, it is only through united working class struggle that women’s rights in the workplace can be defended and improved.

The problem we have is that today’s trade union leaders are not leading the fight but in spite of these limitations, “The wages of women union members are on average 30% higher than those of non-unionised women”. This reveals how historically the trade unions have been essential in raising women’s wages. Although there remains much to be done, the trade unions have played a key role in improving women’s wage levels and working conditions.

This applies to workers in general, both men and women: “The average hourly wage for non-unionised workers in the private sector is £12.64. For union members, it’s £13.67. The ‘union premium’ is even bigger for young workers from ages 16-24, who earn 39% more than their non-unionised colleagues (that’s £7.84 to £10.18)” [Source: strongerunions.org].

The overall workforce in Britain is now over 29 million strong. Working women account for 15 million i.e. 47% of the total UK workforce.

Up to the mid-1980s, trade union membership had been growing, having reached around 45% of the overall workforce. Since the defeat of the 84-85 miners’ strike, however, membership has been in decline. Currently 6.4 million people are in a union – less than 25% of the workforce.

Getting organised

Women make up a majority, 55%, of the overall trade union membership, with around 3.5 million women in the unions, making the trade unions by far the largest women’s organisations in the country. The problem is of course that there are over ten million women who are not organised.

These millions of working women are forced to keep their heads down for fear of losing their jobs. But all of history shows that once the working class as a whole reawakens, women are at the forefront. In the coming period, millions of young women will be forced to stand up for their rights and they will lead the struggle.

They have a lot to fight for and together with demands on wages will also come demands such as good quality childcare available for all parents, more flexible working hours, and the right to take time out of work – for both mothers and fathers – without this endangering women’s jobs and careers.

The women in the unions today and the millions who will come into them in the future will play a key role in transforming the unions and breaking with the culture of moderation and collaboration with the bosses which many union leaders had become accustomed to in the past.

In the process of struggle they will also draw the necessary conclusion that a system based on maximising profits is never going to grant full equality. It is the system that must go.