“After their death, attempts are made to convert [great revolutionaries] into harmless icons, to canonise them, so to say, and to hallow their names to a certain extent for the ‘consolation’ of the oppressed classes and with the object of duping the latter, while at the same time robbing the revolutionary theory of its substance, blunting its revolutionary edge and vulgarising it.”

V. I. Lenin, ‘The State and Revolution’

These words of Lenin were written as criticism of the opportunist degeneration of the Second International, and principally of the German Social Democrats. Under the corrupting influence of the capitalist class, these ‘Marxists’ had transformed Marx into a petty-bourgeois democrat, all while holding up his image and reputation for themselves.

These words of Lenin were also prophetic: describing the transformation that his ideas and legacy would undergo after his death in January 1924. The name of Lenin and Leninism was sanctified and transformed into the foundation stone of an official dogma: ‘Marxism-Leninism’.

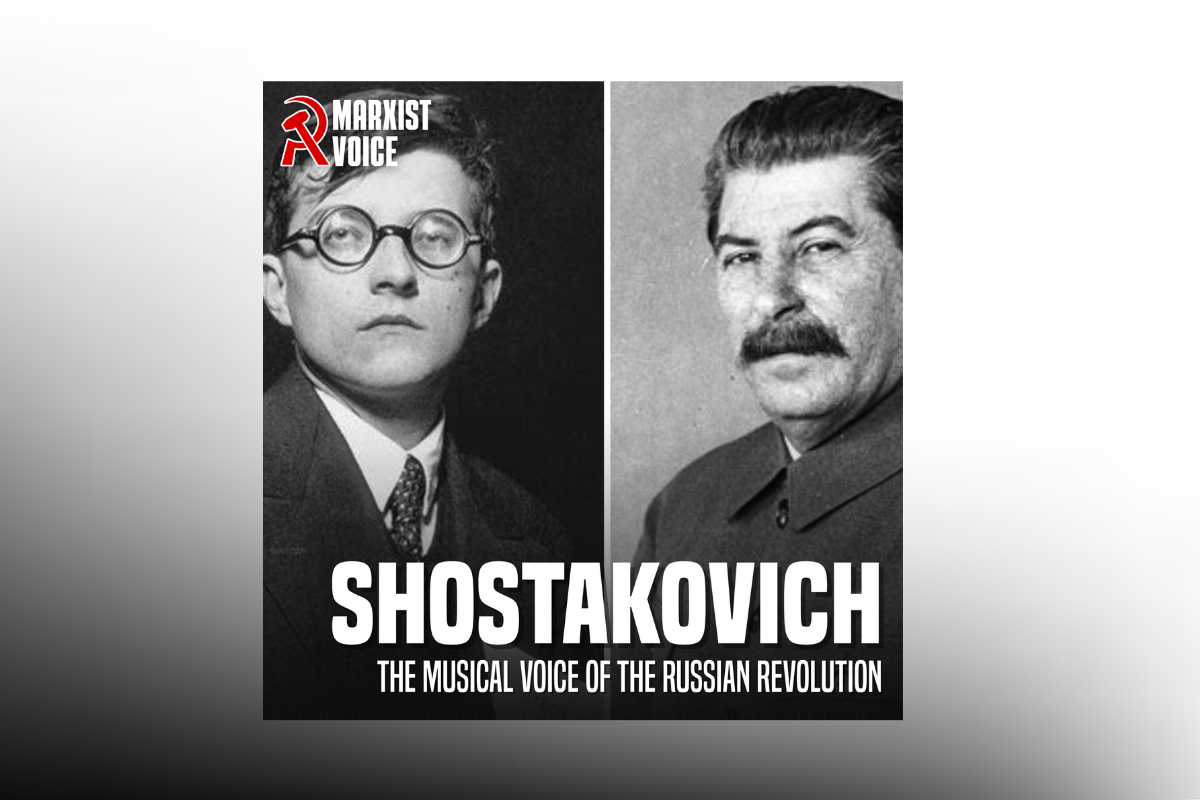

This ideology, however, was not an invention of Lenin. ‘Marxism-Leninism’ is nowhere to be found in Lenin’s works. What would come to be the sordid history of ‘Marxism-Leninism’ is, in fact, Stalinism, not Leninism. Its adherents nonetheless stick to the powerful myth that Stalin was the greatest student of Lenin, and upheld Lenin’s perspective and policy.

Stalin established his regime over the grave of Lenin, attempting to seize the authority of the October Revolution for himself, while twisting and falsifying the history and ideas of Bolshevism.

Communists today must reclaim the real, revolutionary ideas and method of Lenin, in order to rearm the working class for the overthrow of capitalism.

Our ‘Lenin lives!’ event will take place this Sunday (21 January) in London, at Hanover Primary School Sports Hall, N1 8BD. It will also be streamed live on our YouTube channel. You can buy tickets to the in-person event here.

Lenin’s final struggle

Lenin did not underestimate the threat that careerism, officialdom, and white-collar haughtiness represented towards the socialist character of the Soviet state. He stood for the complete opposite.

In his classic The State and Revolution, he laid out four basic principles of a workers’ state that would militate against the scourge of bureaucracy. These were: no official to receive more than a skilled worker’s wage; no standing army but the armed people; the rotation of all administrative roles amongst the workers (‘when everyone is a bureaucrat, no one is a bureaucrat’); and the right of workers to recall their elected representatives at any time.

Here we see the real Lenin: an enemy of privilege, prestige, and officialdom, and a partisan of working-class power. As Lenin declared after the October Revolution:

“Comrades, working people! Remember that now you yourselves are at the helm of state. No one will help you if you yourselves do not unite and take into your hands all affairs of the state…

“Socialism is not created by orders from on high. It is a stranger to mindless, official bureaucratism. Living, breathing socialism is the creation of the popular masses themselves.”

In one of his final letters, Better Fewer, But Better, Lenin sharply criticised the state apparatus of the Soviet Union:

“Our state apparatus is so deplorable, not to say wretched, that we must first think very carefully how to combat its defects, bearing in mind that these defects are rooted in the past, which, although it has been overthrown, has not yet been overcome … ”

Lenin’s comment that “we have bureaucrats in our party offices as well as in soviet offices” was perhaps a pointed remark at Stalin, who as general secretary of the party had amassed a legion of officials serving at his discretion.

These inflictions were undermining the soviets from within, threatening to alienate the masses or divert them from the class struggle. With his characteristic insight, Lenin was able to see the roots of bureaucratism within the material and class conditions of the Soviet Union: namely, its economic and cultural backwardness.

The Bolsheviks were under no illusions about what country they led: a semi-feudal autocratic empire, devastated by imperialist invasion and economic collapse.

In such conditions, the Marxist programme of raising the working class to power and socialising production to end the scourge of poverty would prove to be a drawn-out and bitter crusade. Lenin was never afraid to openly admit this, and remind the proletarian vanguard in Russia that they were still struggling against the past.

View this post on Instagram

Bureaucratisation

Through the collapse of the Tsarist regime and the brutality of the Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks had held onto power by building the centralised soviet state apparatus, resting on the support of the urban working class and the rural peasants.

The Bolshevik government acted as the revolutionary dictatorship of the working class, with the masses exercising democratic control over the state through the elected soviets.

Due to the privations of war, however, the soviets themselves became only a shell of what existed in 1917. Many of the best rank-and-file communists died fighting for the Red Army. The collapse of industry, meanwhile, resulting from the blockade of Russia by the imperialists, meant a practical disintegration of the industrial proletariat.

The basis of the soviet system – the political and economic self-organisation of the working class and poor – was deeply eroded by the daily struggles for survival.

The vast Russian population itself was overwhelmingly non-proletarian, made up of petty-bourgeois peasants, the majority of whom were illiterate. Among the better educated, whose services would be necessary in the administration of the workers’ state, the majority were bourgeois; either hostile or indifferent to the cause of socialism.

The result was that, by the end of the Civil War, an unprecedented number of soviet officials, secretaries, committees, delegates, and so on became appointed rather than elected. Non-proletarian or semi-proletarian elements began to fill the state apparatus.

This was an unavoidable expression of the small size, and the lack of education, of the exhausted Russian working class. But the situation threatened to sideline the working class and undermine the revolutionary foundations of the Soviet Union.

Lenin understood this danger, and appealed to the assistance that the spread of the proletarian revolution to more advanced countries could provide, as an essential condition for the victory of socialism in the USSR.

Despite his poor health, Lenin insisted on sharing his views with the party. He called for stronger collective leadership and political control over the state and party apparatus, and for a concerted effort to be made to train up genuine communists for the tasks of state administration.

Weeks before his death, Lenin would dictate a final letter – his ‘testament’ – to the party congress, in which he assessed the strengths and shortcomings of all the top Bolsheviks. Most notably, Lenin singled out Stalin for demotion, judging him unfit to be party general secretary any longer.

View this post on Instagram

Legend of Trotskyism

From the early roots of bureaucratisation, the administrative apparatus of the Soviet Union would grow into an enormous burden on the working class. The millions of state officials rewarded themselves with pay bonuses, special incentives, and privileges.

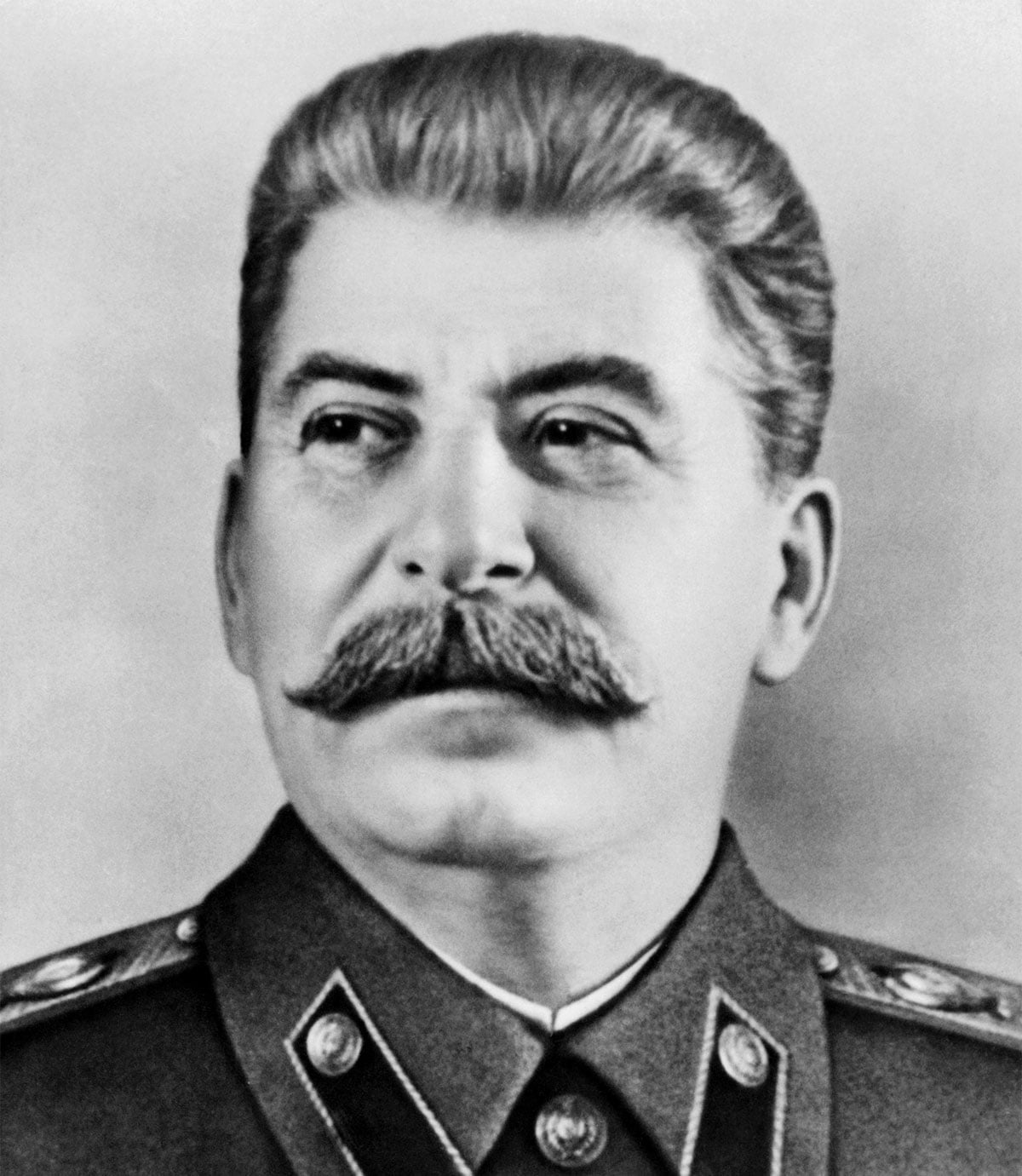

At the top of this heap of party and state offices was the ruling clique, among whom Stalin first took the place of the ‘Number One’.

Stalin’s rise to the top was not, it must be said, planned out in advance. Stalin advanced by reflecting the bureaucracy’s interests, and, in a step-by-step manner, acting accordingly.

Trotsky, on the other hand, had formed a bloc with Lenin to take up the struggle against bureaucracy. This had already begun to irk the Stalin-Zinoviev-Kamenev Troika prior to Lenin’s death, knowing they were the targets for this criticism.

The Troika’s first display of their bureaucratic power was to ensure that Trotsky’s platform was rejected by the party congress, and that his opposition to the Troika was ruled a deviation from the party line. This they achieved with the help of the invention of ‘Trotskyism’, as something distinct from Marxism and Leninism.

Trotsky would fill Lenin’s position as the harshest critic of the Soviet bureaucracy. Stalin and his allies denied the danger of bureaucratic degeneration in the party and state apparatus, denouncing such criticisms as an attack on party unity. At the same time, they prevented opposition delegates from being elected to the congress, and began a behind-the-scenes campaign to politically isolate Trotsky.

The Left Opposition that Trotsky led against the Troika was not just formed over the question of bureaucracy, but in fact over problems of economic development in the USSR and the strategy of the world revolution.

Internationalism

As with Lenin, Trotsky was insistent that the only genuine solution to the economic and political problems in the Soviet Union, rooted as they were in Russia’s relative backwardness, was the intervention of the working class in Western Europe. This position had been explained by Lenin a thousand times, and was widely known among the Bolsheviks.

Lenin avowed internationalism not just in words, but in deeds. As far back as 1915 he had seen the need for the creation of a new, revolutionary International following the betrayal of the Second International, which supported the imperialist world war.

Lenin and the Bolsheviks founded the Communist (Third) International in 1919, understanding as he did that it would be impossible to build socialism in one country, not least a backward country like Russia.

This was not a perspective shared by the bureaucracy however, which was cynical about the possibilities of spreading the proletarian revolution from the USSR. The bureaucracy instead preferred to stabilise relations with the capitalist world and secure its social existence within the Soviet Union.

The ruling bureaucracy thus had to overthrow the ideas of Lenin, and replace them with guiding principles that served their own interests. This ideological excrescence is the real origin of the ‘Marxism-Leninism’ of Stalin and others.

The Troika began the persecution of the ‘Trotskyist’ opposition, which came to include anyone who raised doubts or criticisms over the socialist character of Soviet policy. Eventually the name of Trotsky would be so blackened, a charge of ‘Trotskyism’ was made synonymous with counter-revolutionary terrorism and treachery.

Just over a decade after the death of Lenin, Stalin turned the accusation of ‘Trotskyism’ on his former Troika allies, Zinoviev and Kamenev. Both were executed as part of the show trials and purges in the 1930s, along with many of the remaining revolutionaries who dared remember the real Lenin.

Bureaucratic counter-revolution

The purges were the culmination of the bureaucratic counter-revolution taking place in the Soviet Union. It meant the physical destruction of the Bolshevik Party of Lenin, and of any oppositional or independent elements in the soviets.

The programme of expunging the true legacy of Lenin, restraining the Soviet working class, and ruling over it with a brutal police state had been accomplished.

A cult of personality was built up around Stalin, that in many respects was also a cult of Lenin. Stalin garnered all his supposed intellectual authority from being the ‘first disciple’ of Lenin, and following in the footsteps of Lenin. This myth would become totemic within the Stalinist USSR, turning Lenin into a “harmless icon” as he described in The State and Revolution.

Through the stormy interwar period of revolution and counter-revolution, this bureaucratic capture of the Soviet state would have disastrous consequences for the whole international working class.

Within the USSR, and through the Communist International, the bureaucracy would announce sharp turns and reversals in policy – to the left and to the right – as it struggled to cope with the shifting tides of the class struggle. In doing so they hoped to achieve a stable equilibrium.

Failed revolutions in China, Spain, and elsewhere were the product of the bureaucracy’s strategic errors, wasting the powerful revolutionary energies of the proletariat on disastrous programmes that violated every principle of Lenin.

Each defeat for the working class only strengthened the disillusionment among the Soviet workers, and ultimately empowered the conservative bureaucracy.

Prestige politics

The government of Stalin – made up of personal favours, secrets, lies – could not be more different to the government of Lenin in the early years of the Soviet republic. At that time, serious questions could be discussed relatively openly among communists, and the state was attentive to the needs of the people.

Lenin understood that you cannot build socialism with prestige politics, i.e. with unprincipled deals on a careerist basis.

In 1917, Lenin was even prepared to step down from his positions in the leadership of the Bolshevik Party to fight for what he believed was necessary – an insurrection to overthrow the bourgeois provisional government. This was a position most of the party’s leaders (including Stalin) initially opposed.

Under Stalin, political ideas were not a sign of conviction but of loyalty, which could be used to reward or punish within the bureaucratic hierarchy. Any and all could be under suspicion. Even those who most loudly professed their loyalty to Stalin and to Marxism-Leninism were never entirely secure in their position.

The bureaucratic elite that Stalin served as figurehead eventually turned on him, however. In his infamous secret speech, Nikita Khrushchev – the new ‘Number One’ of the ruling group – condemned Stalin’s mass persecutions, abuses of state power, and cult of personality.

Class collaboration

After Stalin’s death, the Soviet bureaucracy only underwent further degeneration. Khrushchev soon announced the call for ‘peaceful coexistence’ between socialism and capitalism.

This marked the final abandonment of class struggle by the so-called ‘Marxist-Leninists’. In fact, this was an inevitable result of the trend of the governing bureaucracy towards a compromise with imperialism.

Stalin had already made many such compromises in his time: from the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Hitler, to the Yalta and Potsdam deals with US and British imperialism. In 1943, he unilaterally wound up the Communist International at the behest of his ally Roosevelt.

At the end of the Second World War, Stalin was even convinced that revolution and proletarian dictatorship were not necessary for some countries to become socialist, proposing the path of ‘People’s Democracy’ and class collaboration, rather than conflict.

This reformist idea itself was only an outgrowth of the bourgeois ‘Popular Front’ alliances that Stalin favoured prior to the war, subordinating the working class to bourgeois democracy.

These policies are the fruit of Stalin’s original revision of Lenin, and his theory of ‘Socialism in One Country’, introduced in 1924.

The Stalinist bureaucracy hoped constantly to neutralise the threat of imperialism towards the USSR by granting concessions. In some countries this meant holding back the proletarian revolution, or diverting it down reformist paths in others. This was pursued in the hope that it would help curry favour with the capitalist politicians of said countries.

This is still apparent in the programme of the British Communist Party, Britain’s Road to Socialism, which was originally drafted with input directly from Stalin after WW2.

A Marxist reader of this pamphlet will find glaring omissions surrounding the questions of the proletarian state and the world revolution. Instead, its advocated parliamentary road to socialism bears out the reformism inherent in Stalinism.

This Stalinist reformism would eventually undergo its own splits and transformations, giving rise to avowedly reformist ‘Eurocommunists’ and postmodern or ‘New Left’ intellectuals. After the collapse of the USSR, many of the former Stalinist ‘Marxist-Leninist’ bureaucrats seamlessly transitioned into being the bourgeois-liberal and conservative wings of the new capitalist order.

View this post on Instagram

After Stalinism, back to Lenin

For a long period throughout the 20th century, the world communist movement was driven to a low ebb by the millstone of ‘Marxist-Leninist’ dogmas around the necks of countless communists. In many countries, revolutionary movements failed thanks to Stalinist leadership.

It is true that in a number of countries, Stalinist parties came to power and capitalism was abolished, which was an enormous step forward. But, having as their model the USSR, they reproduced its isolated bureaucratic regime, rather than linking up into a federation of socialist states that planned their economies together and pursued the world revolution.

The counter-revolutionary bureaucracy in the Soviet Union eventually ran the Soviet economy into the ground thanks to its bureaucratic methods, which stifled initiative, democratic criticism, and flexibility in the economy.

This stagnation in turn led the bureaucracy to its restoration of capitalist relations, and the complete dissolution of the planned economy, as feared by Lenin and predicted by Trotsky.

This tragedy is still not understood by the contemporary adherents of ‘Marxism-Leninism’, for whom it was like a lightning bolt from a clear blue sky.

Today we must pierce the myth that communism is synonymous with Stalinism, or that the example of Lenin can be defined through the practice of ‘Marxism-Leninism’.

Stalinism is not Leninism. The accumulated actions, writings, advice, and ideas of Lenin are the only Leninism that we need to make reference to. This is the genuine tradition of communism, as the theory and practice of world proletarian revolution.

In this, the ideas of Lenin still stand tall. Going back to the original Lenin, who struggled to build the Bolshevik Party and establish the first Soviet republic in history, there are countless lessons for our current epoch.

View this post on Instagram