Adam Booth reviews the latest film by acclaimed socialist director, Ken Loach, which shines a light on the harsh and degrading conditions faced by thousands – if not millions – in this age of austerity.

“I am not a client, a customer, nor a service user. I am not a shirker, a scrounger, a beggar nor a thief. I am not a national insurance number…My name is Daniel Blake; I am a man, not a dog. As such, I demand my rights. I demand you treat me with respect. I, Daniel Blake, am a citizen – nothing more, nothing less.”

These powerful words by the protagonist of the new film by left-wing director Ken Loach, out in cinemas now, have appeared on social media feeds, billboards, and even the daunting walls of the Houses of Parliament in recent weeks. They portray the desperation of the film’s eponymous central character in his struggle to survive and retain his dignity in the face of the grinding misery and toil of modern-day Tory Britain. But, as the movie’s trending hashtag #WeAreAllDanielBlake suggests, Daniel’s story, whilst fictional, is by no means unrealistic or isolated. Indeed, the most tragic part of Daniel’s tale is how ubiquitous such stories are in this age of austerity.

The heart of a heartless world

The film’s initial dialogue over the opening credits set the scene for the rest of the movie: one man, alone and impotent, fights in vain against a system that is stacked against him, designed to demoralise and destroy all sense of self-respect until he gives up and disappears from sight. Retaining his humour in the face of a cold-hearted bureaucracy, Daniel makes a futile attempt to explain to an Employment and Support Allowance “decision maker” that he is not unwilling to work, but unable to on doctor’s orders as a result of a problem with his heart.

The brutal – and yet beautiful – irony of the film, however, is that Daniel is one of the few people to have any heart in this heartless world. It is not his heart that is broken, but the system that surrounds and envelops him and those in similar conditions.

In scene after scene, we see with touching simplicity the manifold acts of kindness and solidarity that Daniel – a native Geordie – carries out without a second-thought towards his neighbours, friends, and even strangers. And yet he demands nothing in return, refusing out of pride and stubbornness the reciprocity offered, determined not to be seen as “a shirker, a scrounger, a beggar or a thief”.

Cast adrift by capitalism

Turning away the opportunity to work and earn a wage due to the condition of his health, Daniel is forced to sell all his worldly possessions in order to pay the bills, rather than accept any charity. Loach shows us, however, that Daniel is not without skill or talent; he is an expert carpenter and general handy-man, with an abundance of experience and ingenuity. He wants to work and put his skills to use. But – like so many others – he finds himself cast adrift in the modern world, lost in a sea of computers and smart phones, unable to keep up on the treadmill of capitalist change.

Facing hurdle after hurdle in order to work his way through the labyrinthine and Kafkaesque machinery of the Job Centre and the wider Department for Work and Pensions, the camera lingers on our protagonist at each stage of his struggle, sighing at his apparent failures – the sigh of the oppressed creature. He is made to feel inadequate and incapable by the condescending benefits officers who act as stern gatekeepers to the safety net that he so desperately needs and deserves. But those around and close to Daniel do not see incompetence; rather, they see a highly talented individual who has been consigned to the scrapheap of society by a system that is incapable – as Daniel notes – of providing a decent job for all.

Through a display of solidarity towards a similarly frustrated “service user”, Daniel strikes up a friendship with a single mother, Katie, and her two children. Offering her and her kids something that nobody else does – attention, care, and respect – Daniel and Katie support each other as they attempt to navigate the numerous challenges placed in their path. Both attempt to retain a sense of stoicism in the face of adversity, but at certain points the pressures overwhelm them, with Katie in particular forced to denigrate herself through acts of theft and prostitution.

In turn, the reality of live for thousands – if not, millions – is displayed in heart-wrenching manner by the director Loach as Katie, after days of starving herself in order to ensure that her kids can eat, attends a food bank for the first time. Unable to control herself due to famine and fatigue, Katie temporarily morphs into the animal that Daniel is so desperate to avoid becoming, breaking open a can of beans and eating them raw in the middle of the community hall in order to alleviate her crippling hunger.

Contempt of the ruling class

Loach’s latest offering has faced sharp criticism from patronising reviewers in the right-wing press, who have painted the socialist director’s film as portraying “an absurdly romantic view of benefit claimants”, with “two protagonists [who] are a far cry from the scroungers on Channel 4’s Benefits Street”; “welfare claimant[s] as imagined by a member of the upper-middle class metropolitan elite.” Such banal rhetoric, however, is an accurate reflect of the contempt that the ruling class and their representatives have towards the working class – precisely the Establishment contempt that I, Daniel Blake highlights through the prism of the titular character’s battles with the bureaucracy and needless red tape of the state.

The real tragedy, as mentioned above, however, is that Loach’s film – far from being “inaccurate” and “exaggerated” is such a graphic and hard-hitting depiction of the genuine conditions faced by thousands and millions of the most poor, oppressed, and vulnerable in austerity Britain. Indeed, figures revealed this week by academic studies show a clear link between the kind of benefit sanctions that Daniel Blake is threatened with and the use of food banks that Katie and hundreds of thousands of others are forced to turn to.

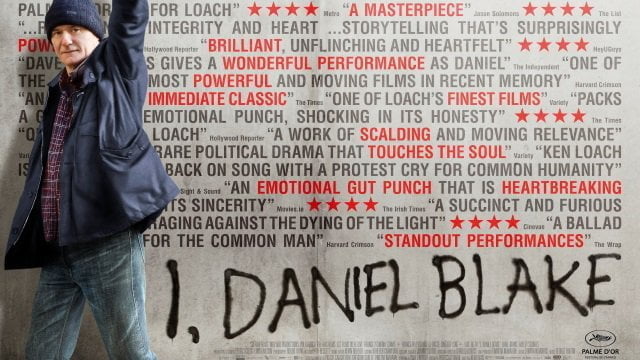

Loach’s film, winner of the Palme d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, is deserving of its accolades for the work it does in shining a light on the denigrating treatment that welfare claimants have to endure. But that does not mean, however, that the movie and its director are beyond reproach.

A question of leadership

Two fundamental flaws lie at the heart of Loach’s film. Firstly, the target of the film’s criticism seems to lie mostly with the bureaucratic system faced by Daniel and Katie, rather than with the politicians who have created this system and – more importantly – the interests that they defend. Throughout the film, the main villains are the DWP officers who callously treat Daniel and fellow claimants as mere numbers on a screen; public sector workers who are themselves, in reality, the victims of Tory austerity and privatisation. Indeed, the only mention of the Tories is from a drunkard – the sole voice of reason – who applauds Daniel’s act of defiance outside the Job Centre whilst berating the government, and in particular Iain Duncan Smith, the former secretary for the DWP and key architect of the recent attacks on the welfare state.

It may well be that it was Loach’s intention not to make the film overtly “political”; perhaps he is merely highlighting how the very people who face the brunt of Tory attacks are the ones with the least time or capacity to engage in political activity. Atomised and stripped of their dignity, Daniel and Katie are too busy desperately trying to make ends meet to be able to think about politics.

In choosing such an angle, however, Loach – whether consciously or inadvertently – paints a picture of almost complete nihilistic despair and pessimism. In the acclaimed director’s previous films, there was always a sense of light at the end of the tunnel; a protagonist filled with revolutionary passion, principles, and optimism. But with I, Daniel Blake there is no rallying cry or call to arms. Indeed, when Daniel does attempt to make a stand by spray-painting a statement of protest on the walls of his local Job Centre, the only support he receives is from a hen party, a drunk man, and a pair of young people wanting a selfie.

Far from giving people confidence to organise and fight back against the Tories and their programme of austerity, then, Ken Loach merely plunges the audience into a pit of despair. It is true that “we are all Daniel Blake”; but solidarity towards the victims of cuts and Tory attacks is not enough. As Loach himself correctly highlighted in previous offerings, it is ultimately a question of leadership.

Loach, a lifelong socialist and activist, has been a vocal force in support of Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party. What is needed now is for such leaders of the Corbyn movement to show the way forward and complete the revolution inside the Labour Party: to transform the Party and the movement around it into a fighting, mass campaign against the Tories, against austerity, against capitalism, and for a bold socialist alternative. Only in this way can we achieve the rights and respect that Daniel – and millions of others like him – deserve.