For the soldiers on the battlefields and in the trenches, the so-called ‘Great War’ – in reality, the ‘Great Slaughter’ – was a seemingly unending nightmare. For the civilians on the home front, especially the women, hardly less so.

In the end, large tracts of Europe lay wasted. Millions were dead or wounded. The great majority of casualties were from the working class.

Survivors lived on with severe mental trauma. The streets of every European city were full of limbless veterans. Nations were bankrupt – not just the losers, but also the victors.

This bloody conflict was brought to an end by revolution – a fact that has been buried under a mountain of myths, pacifist sentimentality, and lying patriotic propaganda.

By 1917, in all the belligerent states, the discontent of the masses was growing. In particular, the people of Germany were beginning to suffer food shortages, which sparked off riots and mass strikes across the country.

There were mutinies in the armies and navies of Italy, Austria, France, and Britain. In August 1917 sailors at Wilhelmshaven were the first to mutiny.

Brest-Litovsk

Internationally, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 had a profound effect. In the factories and trenches it sounded a clarion call.

An urgent priority for the Bolsheviks was to get out of the war. The Russian army was disintegrating. On the Eastern Front there was mass fraternisation between Russian and German soldiers. They met together in no-man’s land: exchanging caps and helmets; sharing vodka and schnapps; embracing and dancing together. Even some officers joined the festivities.

But the party was not allowed to last. The German general staff realised the danger of this fraternisation and ordered a new advance. The Russian army was in no position to resist.

The war-weary peasants in uniform threw away their rifles and deserted en masse to return to their villages. The Russian army was rapidly collapsing. The Germans pushed deep into Russian territory.

A truce was hastily called, followed by a peace conference at Brest-Litovsk that ended Russia’s participation in the war.

As leader of the Bolshevik delegation, Leon Trotsky skilfully used the negotiations as a platform to launch revolutionary propaganda, directed at the soldiers and workers of the belligerent powers.

Trotsky strove to stretch the discussions out in the hope of a revolution in Germany and Austria that would come to Russia’s aid. His speeches, which were translated into German and other languages and widely distributed, did have a considerable effect.

The revolutionary events in Russia transformed public opinion in Austria-Hungary. The rebellious mood was reflected in a wave of factory strikes. But the development of the revolution in Austria-Hungary and Germany needed time. And for the Russian Revolution, time was running out.

The Bolsheviks had no army to defend the Soviet power. The old tsarist army had practically ceased to exist, and the Red Army had not yet been created. Threatened by enemies on all sides, the Bolshevik Revolution was in danger of being throttled at birth.

The German army advanced and seized control of Poland, the Baltic States, and the Ukraine. The Allied powers also intervened: the French in Odessa, the British in Murmansk, and the Japanese in the Russian Far East.

Under these circumstances the Bolsheviks were compelled to accept the harsh conditions imposed by German imperialism at Brest-Litovsk.

This was a heavy blow. But it gave the Bolsheviks a breathing space, to allow time for the revolution to develop in Europe. And they did not have long to wait.

Austria-Hungary

The sailors, being mainly drawn from the proletariat, were particularly active as a revolutionary force – not only in Russia, but also in Austria-Hungary and Germany.

The warships were like floating factories. And close contact with the officers bred a class hatred that was all the more intense for that.

In Austria-Hungary, the first naval revolts began in July 1917 over a disruption of food supplies. An Austrian submarine defected to Italy in October 1917, provoking fear that Austro-Hungarian forces might succumb to the revolutionary moods that affected the Russians.

By January 1918, hundreds of thousands of workers were on strike in Vienna. Revolutionary sailors actively supported the striking workers at the Pola arsenal. The Slovene, Serbian, Czech, and Hungarian troops in the armed forces mutinied.

The arrival of three light battleships forced the mutineers to surrender. But the uprising was a warning signal to the government.

More than 400 sailors were imprisoned for their role in the mutiny, four of whom were executed.

On 27 October 1918, in the final days of the war, unrest again broke out after the Austro-Hungarian army collapsed in the face of an Italian offensive. Naval vessels were soon operating under the control of their crews.

The crumbling edifice of the Hapsburg Empire tottered and fell under the hammer blows of revolution. Its armies were scattered and broken, and new national governments were springing up in the regions.

The old Austro-Hungarian state had ceased to exist. Power was lying in the street, waiting for somebody to pick it up.

Had there been a Bolshevik Party to take advantage of the situation, the Austro-Hungarian Empire would have gone the same way as its Russian cousin. But the so-called Austrian Marxists were no different than the Russian Mensheviks, and had not the slightest idea of assuming power.

Collapse of Ludendorff’s offensive

Despite the dire state of German morale, both at home and in the army, General Ludendorff launched a series of offensives in the spring of 1918, in what was to be a last desperate attempt to break the stalemate on the Western Front.

Between 21 March and 4 April 1918, in the first round of these suicidal adventures, German forces suffered over 240,000 casualties. Germany’s position was now hopeless.

The German emperor and his military chief, Erich Ludendorff, realised that there was no alternative. Germany must beg for peace.

But the situation was already spiralling out of control. Power was slipping out of their hands.

After years of suffering, a war-weary and hungry country became rebellious. Discontent and hunger were rife in Germany. The whole country was a powder keg waiting for a spark to set off an explosion.

Faced with the threat of immediate revolution, Prince Max attempted to carry out reforms that would transform Germany into a constitutional monarchy. But things had already gone too far.

A rumour that an order had been issued to attack the English fleet in the North Sea sparked off a revolt of the sailors in Wilhelmshaven and Kiel on 30 October. Everybody knew that the war was lost.

The men passed a resolution stating their refusal to take the offensive. The officers replied by arresting some of the sailors, which led to a mass demonstration of the sailors on 3 November.

After being shot at, eight demonstrators died and 29 were wounded. This incident had an electrifying effect on both workers and sailors.

The Kiel workers joined the movement on 4 November, creating the first soldiers’ and workers’ council in Germany.

From Kiel, the mutiny spread quickly to other provinces and cities, such as Lübeck and Hamburg. In Cologne the councils were established within days.

The revolutionary councils demanded an end to the war, the abdication of the Kaiser, and the declaration of a republic.

The councils demanded the release of political prisoners, freedom of speech and press, abolition of censorship, better conditions for the men, and that no orders be given for the fleet to take the offensive.

On 5 November, one northern newspaper wrote:

“The revolution is on the march: What happened in Kiel will spread throughout Germany. What the workers and soldiers want is not chaos, but a new order; not anarchy, but the social republic.”

The German Revolution had begun.

The German Revolution

Within only a few days, the revolt spread throughout the empire, with little or no resistance from the old order.

Within only a few days, the revolt spread throughout the empire, with little or no resistance from the old order.

Everywhere, the workers joined forces with the troops, in an unstoppable mass movement against the hated monarchical regime.

Throughout the empire, workers’ and soldiers’ councils were formed. These moved to take power into their hands. But which party was prepared to take power?

The Social Democratic Party (SPD) had the support of most workers. They now put themselves at the head of the revolution.

But in 1917, the SPD had split into the Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD) and the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD).

On 5 October 1918, the Independent Socialists issued a call for a socialist republic. In Berlin, a committee of revolutionary shop stewards was formed and began to collect arms.

In Bavaria, on 7 November 1918, a mass demonstration of thousands of workers demanded peace, bread, the eight-hour day, and the overthrow of the monarchy.

The next day the Independents organised a constituent soldiers’, workers’, and peasants’ council. And this body proclaimed the establishment of a Bavarian Democratic and Social Republic, headed by Kurt Eisner.

The Greater Berlin Trade Union Council threatened a general strike if the emperor did not abdicate. This was called on the morning of 9 November, alongside mass demonstrations.

A workers’ and soldiers’ council was formed, and the regiments and troops stationed in Berlin were won over to the side of the revolution.

Prince Max had no choice but to announce the abdication of the Kaiser – although no word had been received from that quarter.

Social Democrats in power

In a state of panic, the German ruling class hastily handed power to the only people who they thought could control the working class – transferring parliamentary leadership to the right-wing Social Democrats under Friedrich Ebert, who was working in cahoots with the army.

In a state of panic, the German ruling class hastily handed power to the only people who they thought could control the working class – transferring parliamentary leadership to the right-wing Social Democrats under Friedrich Ebert, who was working in cahoots with the army.

Ebert believed that the simple transfer of power from Prince Max to himself represented the final victory of the revolution. For these gentlemen, the whole purpose of the revolution was merely to bring about a ministerial reshuffle at the top.

But the mood in the streets was very different. Was it for this that the workers and soldiers had fought and died?

The working men and women soon delivered a resounding answer. A mass demonstration of Berlin workers surrounded the Reichstag building, forcing the Socialist leaders to react.

The Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann mounted the balcony and proclaimed to the crowd:

“These enemies of the people are finished forever. The Kaiser has abdicated…Prince Max von Baden has handed over the office of Reich chancellor to representative Ebert. Our friend will form a new government consisting of workers of all socialist parties. This new government may not be interrupted in their work, to preserve peace and to care for work and bread…Everything for the people. Everything by the people…The old and rotten, the monarchy has collapsed. The new may live. Long live the German Republic!”

When Scheidemann came in from the balcony, he was met by a furious Ebert.

“You have no right to proclaim the republic!” Ebert shouted. “What becomes of Germany – whether she becomes a republic or something else – a constituent assembly must decide.”

But the masses had compelled the Majority Socialists to proclaim a republic before the Constituent Assembly had even met.

The very next day, 10 November, the Kaiser boarded a train and fled to the Netherlands, where he would remain until his death in 1941.

The end of the war

The First World War was thus ended by the German Revolution.

The First World War was thus ended by the German Revolution.

At this point it was a bloodless revolution. Only 15 people lost their lives in Berlin on 9 November. We must compare this with the huge numbers who were slaughtered like cattle on the killing fields of Ypres, Passchendaele, and the Somme.

The Social Democratic leaders had the illusion that they would be treated honourably by the victors in the armistice negotiations to halt the fighting. They were sadly mistaken.

The French and British treated the German delegation with complete contempt. They were not prepared to listen to even the most modest proposals for compromise. Revenge was on the order of the day.

The French imperialists were particularly vindictive. Germany was ordered to give up 2,500 heavy guns, 2,500 field guns, 25,000 machine guns, 1,700 aeroplanes, and all the submarines they possessed. They were also asked to surrender several warships, and to disarm all of the ones that they were allowed to keep.

Germany was to be rendered defenceless. If Germany broke any of the terms of the 11 November Armistice, fighting would recommence within 48 hours.

The Armistice was followed by the predatory Treaty of Versailles. Germany was forced to accept the blame for the First World War and pay reparations, estimated at around £22 billion in current money. It was only in 2010 that Germany paid off its war debt.

The systematic plundering of the German people plunged the defeated nation into a deep economic, social, and political crisis. This paved the way for the rise of Hitler – and for a new, even more terrible, world war.

Little did the victors of World War I imagine that just over two decades later, in 1940, another armistice would be signed in the very same railway carriage. But this time it was Germany forcing France to sign an agreement to end the fighting on their terms.

Adolf Hitler sat in the same seat that Marshall Foch had occupied in 1918. The carriage was taken and exhibited in Germany as a war trophy. It was finally destroyed in 1945.

Revolutionary optimism

About 17 million soldiers and civilians were killed during the First World War. One of those who survived was my grandfather.

George Woods entered the war on 1 September 1914 as a young enthusiastic volunteer. He is listed as private number 13793 of the Welsh Regiment, and served nine spells of action in France in a period of five years.

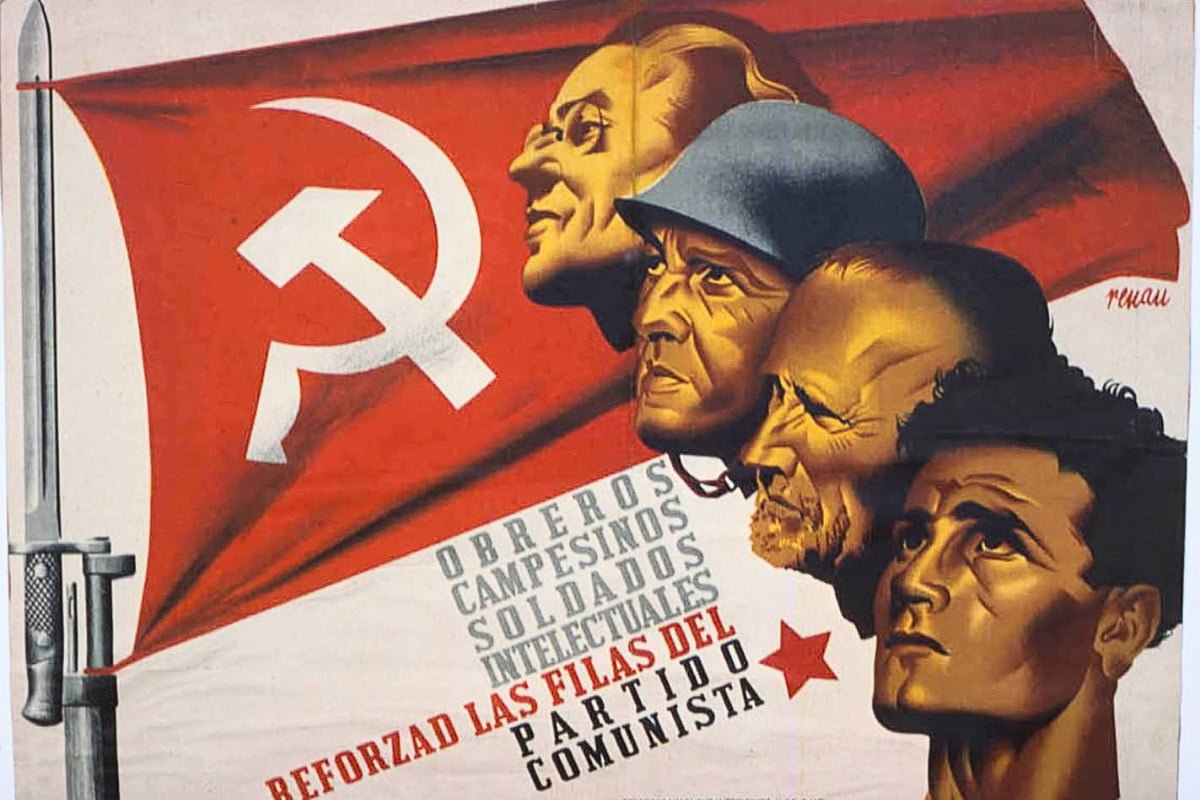

He left the army a changed man. Inspired by the example of the Russian Revolution, he joined the Communist Party and remained a committed communist until he died.

I learned about the ideas of Marx and Lenin – about the class struggle and the Russian Revolution – from him. I am eternally grateful to him for this and so many other things.

My grandfather, a Welsh tinplate worker, was not alone. The South Wales Miners’ Federation voted to affiliate to the Communist International. In Scotland, the Clydeside shop stewards did the same.

Out of the bloodsoaked ruins of the Great Slaughter, a new spirit of revolt was born. In all the belligerent countries – in Paris and Berlin, in Vienna and Budapest, in Sofia and Prague – millions of workers were on their feet, fighting for change; for a better world; for bread and justice: for socialism.

It is easy to draw pessimistic conclusions from human history in general, and wars in particular. There are always those who draw pessimistic conclusions from the objective situation. Scepticism and cynicism are merely hypocritical expressions of moral and intellectual cowardice.

Such people blame the working class for their own impotence and apostasy. Lenin never showed the slightest sign of pessimism when the nightmare of war and reaction seemed never ending. He showed utter contempt for the pacifists who moaned about the evils of war, but who avoided drawing revolutionary conclusions.

During the dark days of the First World War, the situation facing genuine revolutionaries must have seemed hopeless. Lenin once more found himself isolated in Swiss exile. But he was not afraid to fight against the stream, convinced that the tide would turn.

Lenin dedicated all his strength to educating and training cadres on the basis of the genuine ideas of Marxism. His masterpiece Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism is an immortal monument to his work in the vital field of theory.

In the end, Lenin was proved right. Contradicting all the pessimistic predictions of the sceptical Cassandras, the imperialist war ended in revolution. The Russian Revolution offered humanity a way out of the nightmare of wars, poverty, and suffering.

But the absence of a revolutionary leadership on an international scale meant that this possibility was aborted in one country after another. The result was a new crisis, and a new – even bloodier – imperialist war.

The great wheel of human history turns continuously. It knows great sorrows and great joys. It is a never ending story of victories and defeats. And it teaches us that any situation, however hopeless it may seem, will sooner or later turn into its opposite. We must prepare for this.

Lenin said that capitalism is horror without end. The bloody convulsions that are spreading throughout the world right now show that he was right.

All these horrors are the expression of a socio-economic system that has exhausted itself and is ripe for overthrow.

Middle-class moralists weep and wail about these horrors, but they have no idea what the causes are, still less the solution. Pacifists and moralists point to the symptoms, but not the underlying cause – which lies in a diseased social system that has outlived its historical role.

Now, as then, the conditions are being prepared for an explosive upsurge of the class struggle on a world scale. In the convulsive period that lies ahead, the working class will have many opportunities to transform society.

The power of the working class has never been greater than now. But this power must be organised, mobilised, and provided with adequate leadership. This is the main task on the order of the day.

The power of the working class has never been greater than now. But this power must be organised, mobilised, and provided with adequate leadership. This is the main task on the order of the day.

We stand firmly on the basis of Lenin’s ideas, which have withstood the test of time. Together with the ideas of Marx, Engels, and Trotsky, they alone provide the guarantee of future victory.

Not world war, but an unprecedented upsurge in the class war is the perspective for the period into which we have entered.

The horrors we see before us are only the outward symptoms of the death agony of capitalism. But they are also the birth pangs of a new society that is fighting to be born.

It is our task to cut short these pains, and hasten the birth of a new and genuinely human society.