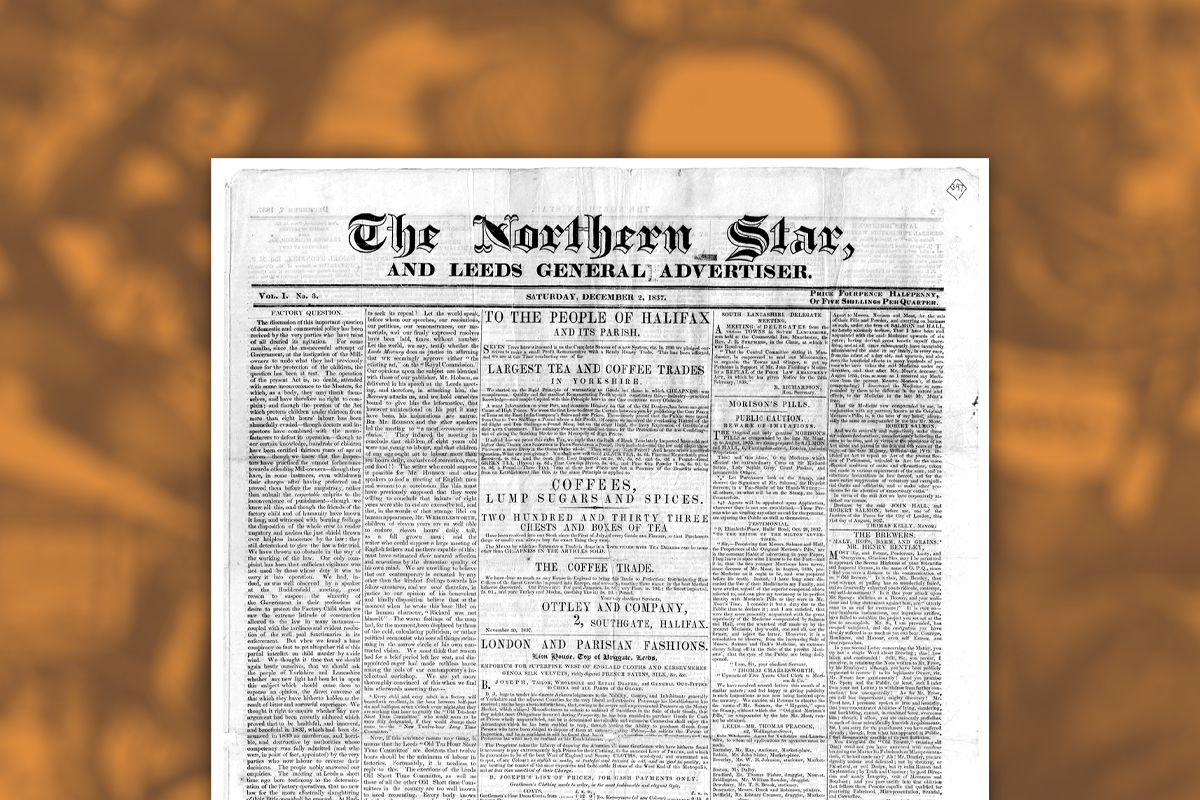

The Great French Revolution was accompanied by a revolution in the press. Whereas the Ancien Régime could boast only one daily paper, between 1789-97 over 1,300 new newspapers appeared, with a combined daily circulation of 130,000.

The press allowed the revolution to communicate with the masses. The struggles within the National Assembly were broadcast to the entire country.

These revolutionary newspapers were not just read, but read aloud: on street corners, in coffee houses, and in clubs. It is estimated that an average copy was read or heard by ten people. Such was the ferment and thirst for ideas.

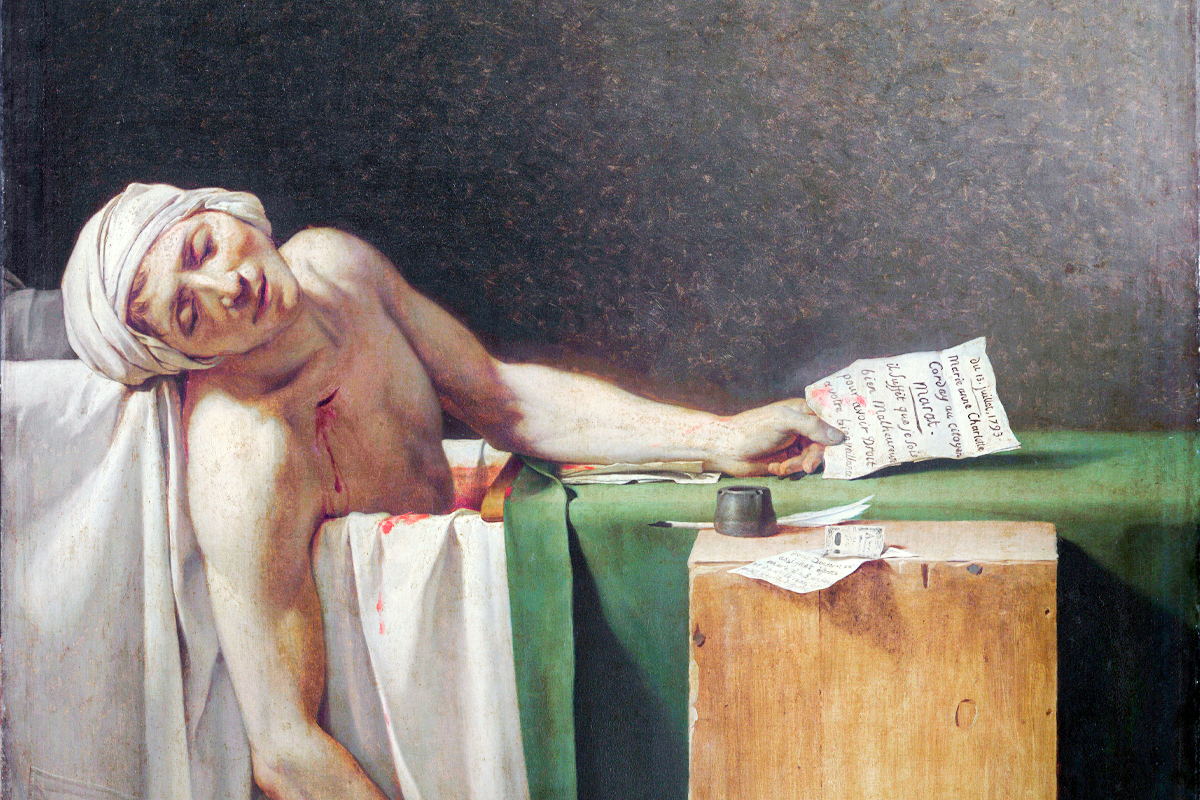

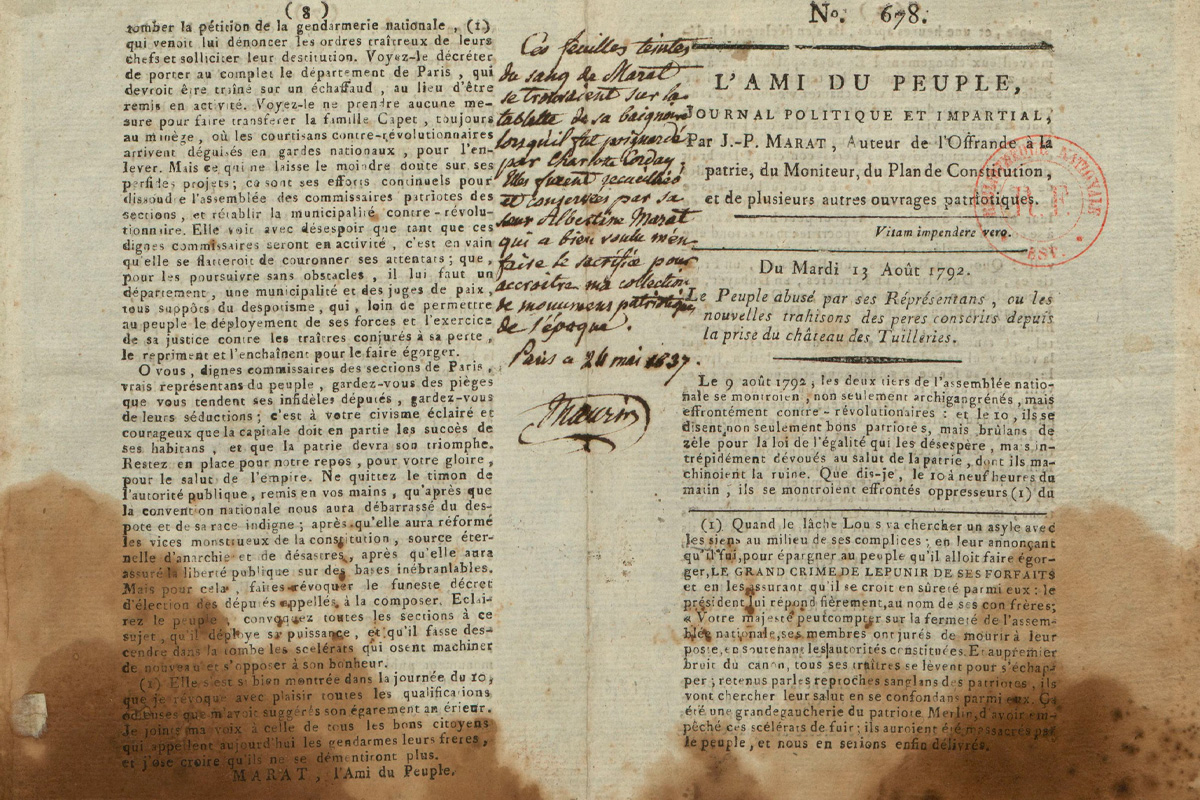

L’Ami du Peuple

The most outstanding revolutionary journalist was Jean-Paul Marat. From 1789, on his own initiative and with his own funds, he published the six-page daily L’Ami du Peuple (‘The Friend of the People’).

Marat was a genuine, zealous revolutionary democrat, who fought not just for political but for social equality.

Marat’s paper became the mouthpiece of the most resolute section of the revolution – the sans-culottes, the urban poor. Over its four-year run, L’Ami printed over 4,000 letters sent in by the impoverished classes.

But the paper was not just an almanac of grievances. As early as 1774, in Chains of Slavery, Marat outlined his conception of a revolutionary organiser:

“As a continual attention to public affairs is above the reach of the multitude…there should never be wanting some men to watch the transactions of the ministers, unveil their ambitious projects, give an alarm at the approach of the storm, rouse the people from their lethargy, disclose the abyss open before them, and point out those on whom the public indignation ought to fall.”

L’Ami du Peuple played precisely this role. It was a watchdog that alerted the oppressed, exposed the intrigues of the counter-revolutionaries, and advocated the most extreme measures to smash all obstacles in the way of the masses.

As a result, the paper was regularly banned, and Marat was forced to hide from repression in the sewers of Paris. To keep L’Ami in circulation, he set up an elaborate secret network of distributors and printing presses, as well as a web of ‘eyes and ears’ – servants in the palaces of the aristocracy, who would disclose their plots.

Behind this technical apparatus, however, Marat was a lone journalist. Unlike Robespierre and the Jacobins, he lacked a party. Once he was assassinated, the paper ceased, and the revolution carried on without him.

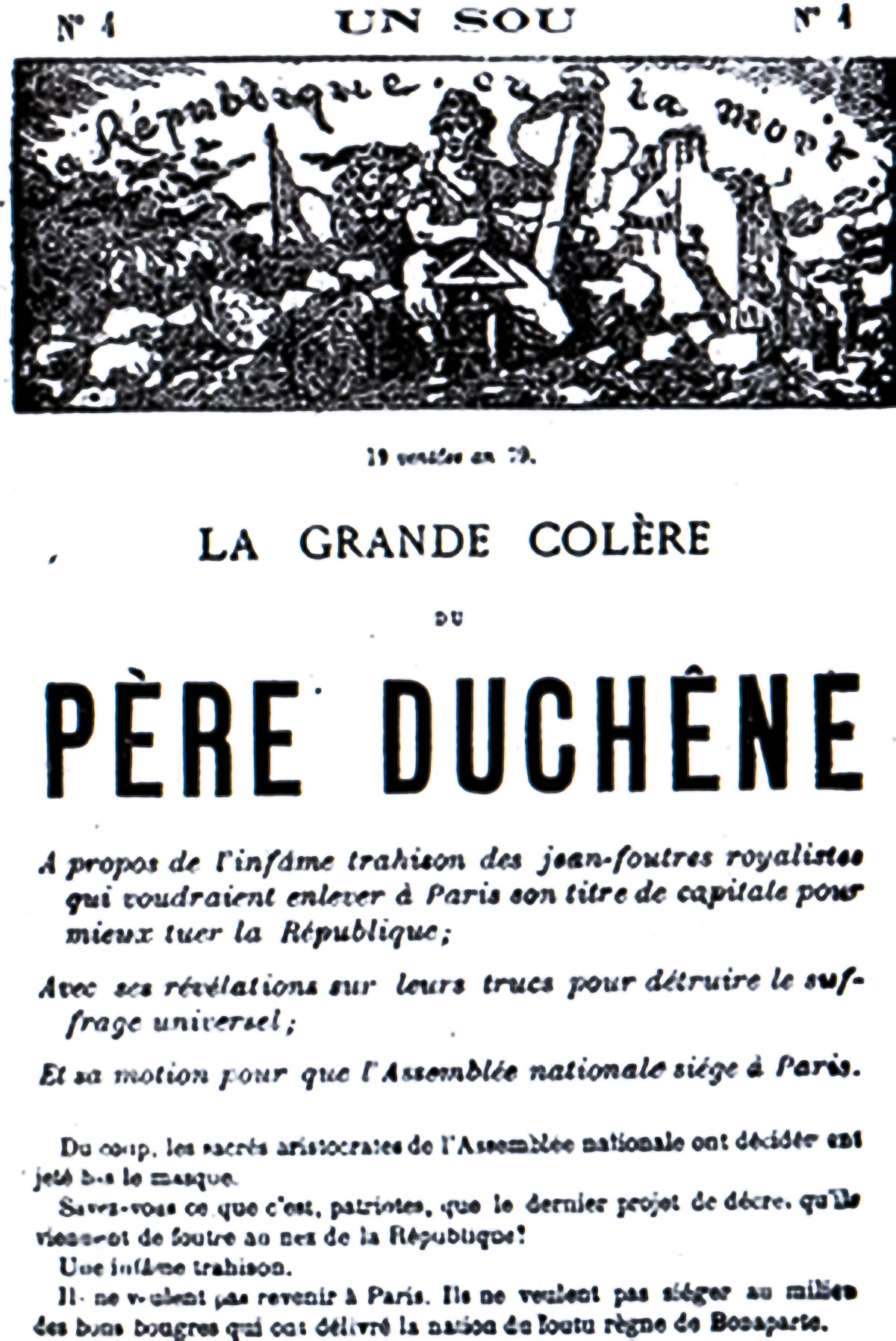

Père Duchesne

After Marat, Jacques Hébert and the Hébertists represented the left wing of the revolution.

Their organ, Père Duchesne – which revolved around a fictional character of the same name – gained extreme popularity. He reflected the coarse, raging voice of the sans-culottes, who denounced their counter-revolutionary enemies.

A typical headline, which would have been read out by streetcriers, was: “The reawakening of Père Duchesne to fuck up the aristocrats and all the enemies of the constitution.”

The paper was less a strategist, as with L’Ami, and more an inspirer to revolutionary action. By 1793, it was being distributed to all the soldiers on the front.

Bourgeois revolution

Both Marat and Hébert were heroic pioneers of revolutionary journalism and organisation. But they were tragically undermined by the circumstances of their time.

Their striving for ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’ for all came up against the straitjacket of capitalism. There could be no genuine liberty or equality under capitalism – not then, and not now.

Only the overthrow of private property could guarantee such rights and freedoms. But this task would fall to the working class that emerged under capitalism.

After the Jacobins had granted land to the peasants and abolished feudal taxes, there was nowhere else to take the revolution. The road was now open to the development of capitalism, which required order and an end to the revolutionary storm and stress.

As the mass movement receded and the revolution began to shift into reverse, the leading Hébertists were beheaded and Père Duchesne was closed. After that, with the exception of a few rearguard insurrections, the sans-culottes were effectively neutralised as a political force.

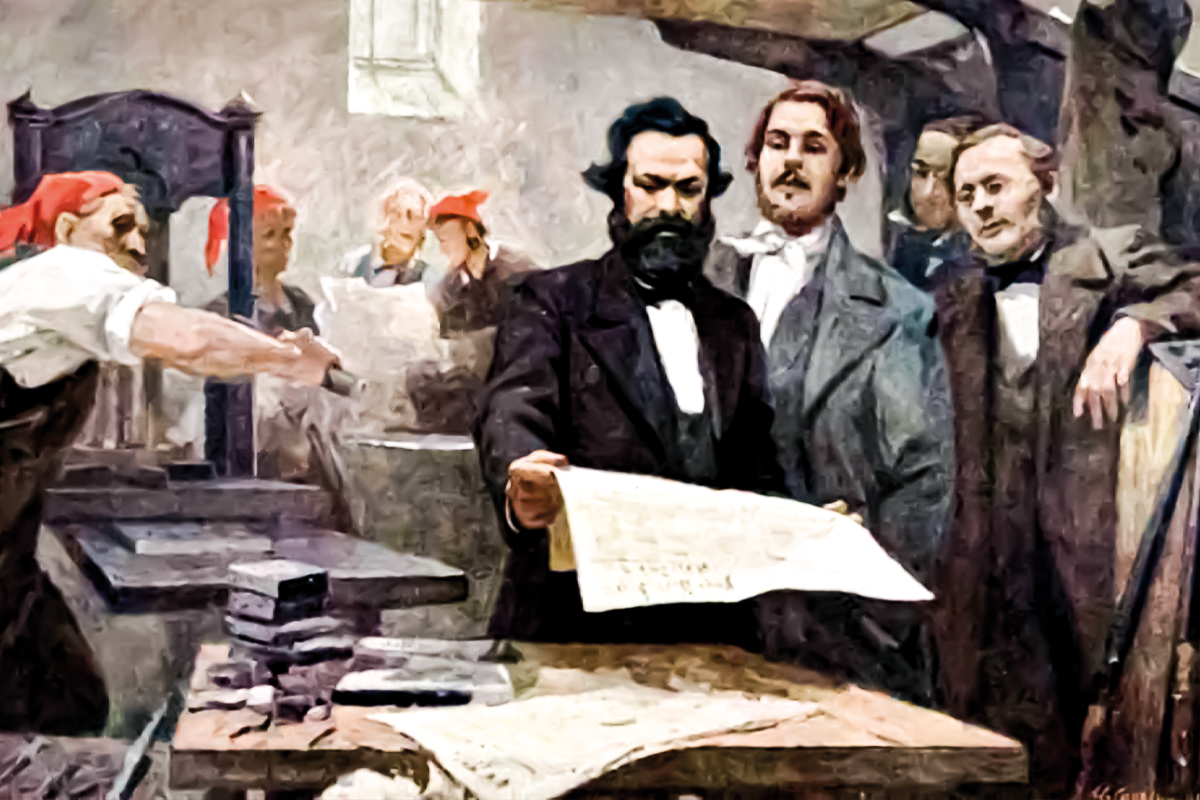

The Communist

We can learn much from the press of Marat and Hébert. Like theirs, our paper must act as a tribune of the masses, one which can organise revolutionaries around a programme of action, and answer the question ‘what is to be done?’ at each stage of the class struggle.

Unlike theirs, however, our paper is not founded on a utopia. The Communist strives to be a workers’ paper: the organ and revolutionary weapon for the most determined class fighters; for the most resolute and radical workers and youth.

Nor is it a disembodied voice. It is a tool for the building of a revolutionary party and of preparing a whole army of communist Marats and Héberts.

Other entries in this series: