“[It is] highly desirable that the lovers of freedom, throughout the British dominions, should have some common rallying point for the muster of their forces – some common organ for the expression of their otherwise isolated opinions and wishes which might bestow upon them that influence and power which are only to be derived from unity and concentration, and without which all our efforts will be unavailing” (The Northern Star, 16 December 1837)

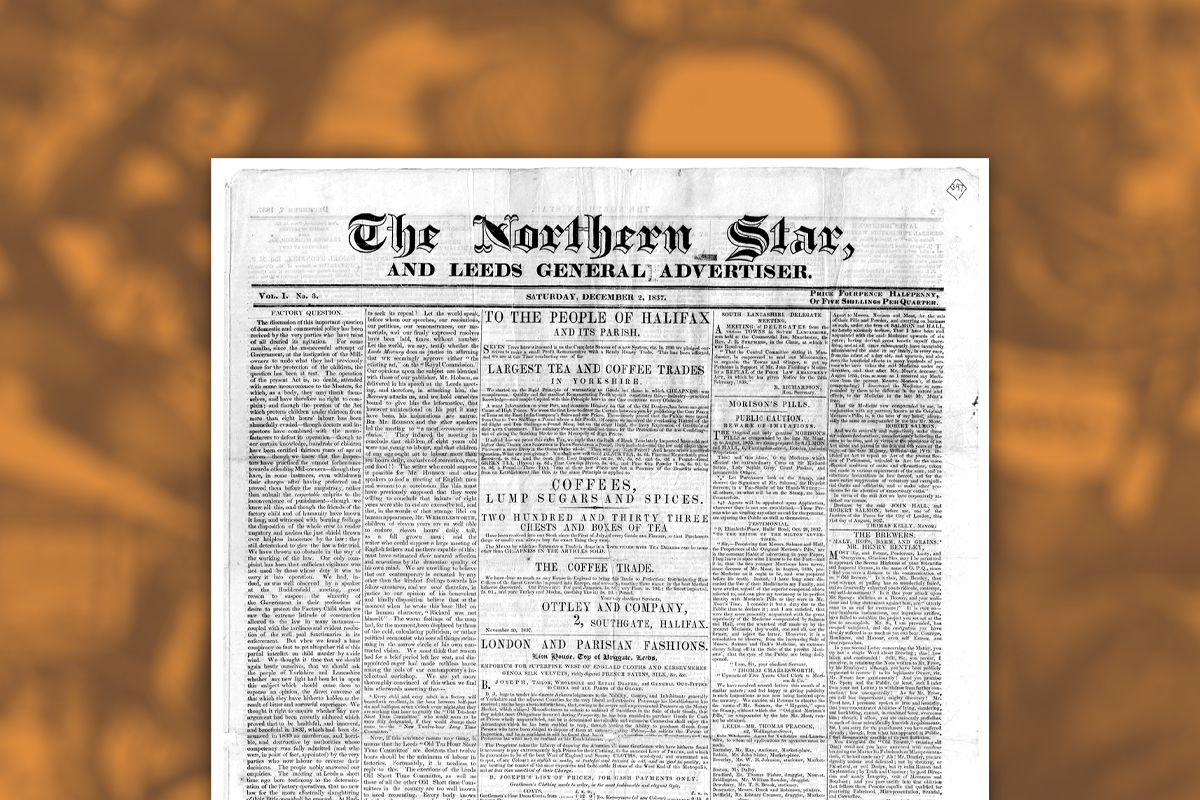

18 November 1837 marked the occasion of the first edition of the Northern Star, with Feargus O’Connor (MP and political radical) at its helm, Joshua Hobson (a former handloom weaver) as printer, and the Reverend William Hill as editor.

In the 1830s, millions of workers engaged in a revolutionary struggle for democratic rights, which became inextricably linked with the fight to emancipate the working class.

The heroic Chartist movement was the first independent working class movement in history. And it was also one of the few times that the British working class came close to seizing power for itself.

The Northern Star became a vital tool for bringing together the forces of Chartism nationally, organising the movement around its production and distribution, and politically arming it through its material.

The war of the ‘unstamped’

The enormous growth of industry was paired with the rise of the working class, which was becoming increasingly aware of its own class interests. The ruling class therefore took steps to censor the workers’ press.

In 1815, the same year the hated Corn Laws were introduced, the Tory government increased the stamp duty – a tax on all newspapers – to 4 shillings, in order to keep the press out of the hands of poor workers.

O’Connor had long advocated for a workers’ press, and participated in the struggle of the unstamped press.

As the MP for County Cork, O’Connor had become frustrated that it was only “beardless Tory, or a doating old Whig [liberal]” who had a medium to freely express their views.

Despite state repression, a number of illegal journals were in circulation, especially during the 1830s. These papers advocated universal suffrage, secret ballots, and annual general elections, coupled with scathing denunciations of capitalism.

A rising tide of working class militancy, particularly in the north of England, eventually led to a reduction of the stamp duty to 1 shilling by the Whig government in 1836, but not its abolition.

The Star succinctly summed up the situation:

“The reduction upon the stamps has made the rich man’s paper cheaper, and the poor man’s paper dearer.”

The Star began its life as a stamped newspaper. In his introductory address to the readers of the Star, O’Connor immediately drew their attention to the paper’s stamp:

“Reader – Behold that little red spot, in the corner of my newspaper. That is the Stamp; the Whig beauty spot; your plague spot…”

While exploiting the advantages which the stamp conferred – free postal delivery and legal publication – the Star was nonetheless imbued with the spirit of the unstamped press, waging ceaseless class war against the ruling class politicians and industrialists.

Rapid success

O’Connor made great sacrifices to get the paper off the ground, fronting £400 (worth over £35,000 today) and took on many of the initial costs and debts.

Unusually the paper was printed in the north of England, the hub of militant Chartism. O’Connor’s links with the Northern radicals raised an additional £500 from Chartist associations in Leeds, Halifax, Hull, Bradford, Huddersfield, Oldham, Rochdale, Keighley, and Barnsley.

From its conception, the Star was funded directly by its readers, the radical working class ranks of the Chartist movement.

The paper sold 3,000 copies of its first issue. Hobson remarked that if they had more stamps they would have been able to sell 3,000 more. Within just four weeks, the paper turned a profit, and quickly became the most successful Chartist publication.

By January 1838, its circulation had reached 10,000, and 50,000 a year later. It was widely circulated during the Bullring Riots in Birmingham, where the question of a general strike was put on the table.

Very quickly, the Star’s offices had to be expanded, and a new printing press constructed. The Post Office reported that issues of the Star would overflow from the mail coaches!

James Guest, Birmingham’s radical bookseller and a veteran of the war of the unstamped, regularly received 3,000 copies a week and sometimes received as many as 7,000.

In 1839, on average the Star would sell 36,000 copies. But contemporary sources suggest that each copy was read by up to 20 people, because they passed from hand to hand in clubs and working-class reading rooms, radical coffee houses, and taverns.

Punctuated with Irish anecdotes, romantic poetry, and his biting sense of humour, O’Connors letters and lead articles were intended to be read aloud to groups of workers.

Workers would gather in their homes to listen to the articles. Similarly, in workshops and factories, breaks would be rife with readings and discussions of its contents.

Collective organiser

Improved transport facilities helped the Star become a truly national paper. It was printed in Leeds on Saturday and could be delivered in London the same evening. This meant it could give an account of both national and local news and meetings.

By printing in Leeds, O’Connor hoped that the spirit of Northern radicalism would imbue itself across the national movement.

The publication of the Star coincided with the height of popular resistance to the New Poor Law. The regions most involved in protesting the law became the earliest supporters of the paper

The Star provided the essential medium of national communication and organisation for the Chartist movement. Before the Star, O’Connor recalls:

“Local opinion was organised at great personal expense, and with much labour and uncertainty. Grievances were a matter of mere oral tradition; and local grievances were resisted by the brave in their respective neighbourhoods, at great risk.”

The Star was a vital tool in transforming local groups of activists into a national Chartist movement.

In its pages, Chartist activists could learn about the proceedings of the National Convention, find accounts of various defence funds, and send their nominations for the National Charter Association.

George White, a Leeds Chartist, maintained that the Star “had been the main cause for keeping the agitation alive… when all their prospects were dark and gloomy… If it had not been for the protection which The Northern Star afforded, [we] would still be as slaves in the desert, and their own sounds might echo through the wilderness.”

Revolutionary Chartism

The leadership of the Chartist movement had long been dominated by middle-class, mostly philanthropic and pacifist elements. Its transformation into a genuinely revolutionary proletarian movement can largely be owed to the influence of The Northern Star.

The Star based itself on the most militant layers of the movement. When the working class Chartists of Birmingham finally broke with their middle-class leaders in the spring of 1839, the hostility of the Birmingham Journal (the organ of the middle-class radicals) to the militant activists, meant that the Star became their only voice.

Chartist meetings often started with readings from the fiery editorials of the Star. Other Chartist papers carried anti-Poor Law news, but these middle-class radical papers increasingly became distant from the real movement.

By contrast, the Star filled its pages with the speeches of local militant Chartist leaders complemented by O’Connors and letters and speeches, all reiterating the need for working class unity behind the single demand for universal suffrage.

Robert Gammage, on the National Executive of the Chartist Association noted:

“The Star was regarded as the most complete record of the movement. There was not a meeting held in any part of the country, in however remote a spot, that was not reported in its columns, accompanied by all the flourishes calculated to excite an interest in the reader’s mind…”

That it was funded entirely by the working class gave it total independence in its reporting. Unstamped papers often had little news and took much of their material from middle-class journals. But this was not the case with the Star, which gave voice to the living movement.

Not only could the Star cover news outside of London, it boasted more original material than any other paper, and claimed to be second only to the Times in how much is spent reporting on events.

Reporting was also an activity which involved local radicals, who were invited to send reports of their meetings and discussions to the Star.

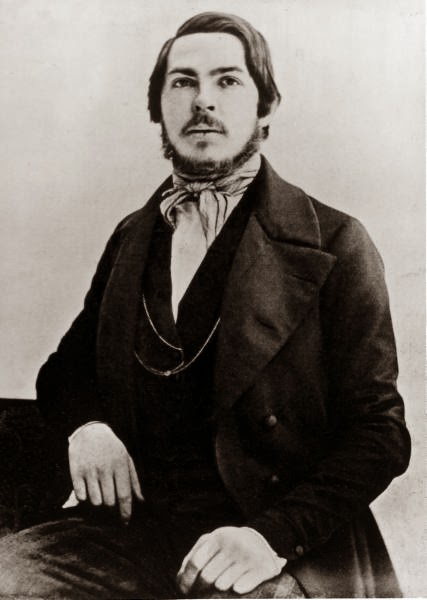

The Star helped O’Connor consolidate his leading role in the movement, and it was in its pages that younger talent such as G. J. Harney and Ernest Jones – both of whom became close friends of Marx and Engels – were able to advance.

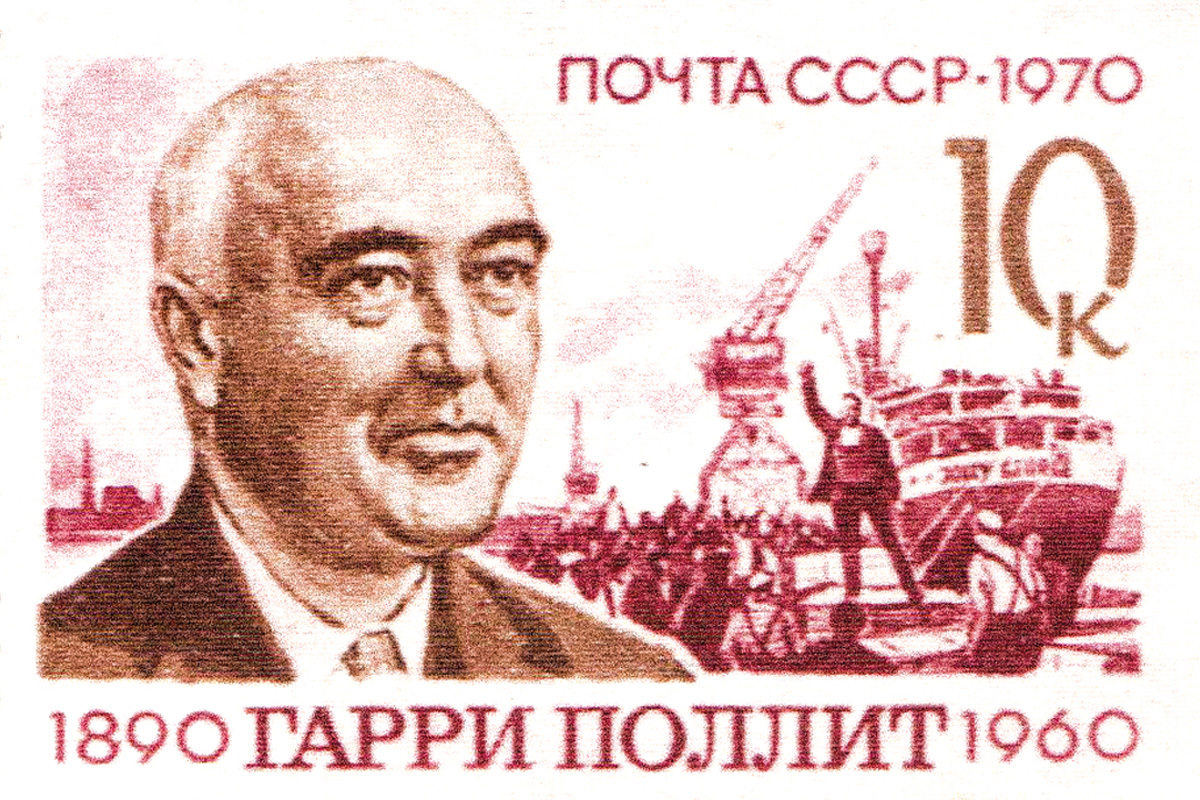

Engels himself, in fact, acted as a foreign correspondent for the paper.

Unlike many radical journals, the Star paid wages to its staff. Most of the unstamped papers’ editors and contributors had worked for very little or for free, often relying on the already comfortable existence of middle class and bourgeois radicals.

In contributing to and then selling the Star, a local working class radical could establish enough of a financial basis to free themselves for full-time Chartist work.

Almost as soon as the Star debuted, O’Connor was planning a more ambitious scheme: a daily London paper in accordance with plans to reorganise the whole movement.

O’Connor believed a daily paper would fulfil the movement’s organisational requirements by providing working class Chartist leaders with the necessary financial independence to undertake full-time agitation.

He outlined a plan of permanent organisation based upon a daily newspaper, the profits of which were to finance lecturers, delegates to Conventions, defence funds and Chartist agitation in general. In 1838 the Star argued:

“The press is at once the cheapest, the most expeditious, and the most certain means of keeping a party together.”

Such a unified centralised party never materialised. When the profits of the Star were placed at the disposal of the movement, this was regarded as an act of largesse by O’Connor.

A workers’ paper

In the Star’s columns ordinary working people were accorded the status of human beings, not for sentimental reasons, but because it was the working class who were pushing movement in a revolutionary direction. One editorial began:

“Beware working men; do your own work, let not rich merchants lead you… Take your affairs into your own hands. We have no rich men leading or driving us but, in the true democratic spirit, manage our own affairs.”

The Star’s success as a newspaper was to the extent that it embodied the aspirations of the working class. Engels noted that the Star was “the only sheet which reports all the movements of the proletariat”.

O’Connor and the editors always insisted that their paper was a “mirror” of the people’s mind. This was central to the very concept of a “people’s paper”.

Thus Rev. Hill wrote on the occasion of the Star’s fifth anniversary in 1842: “I have ever sought to make [the Star] rather a reflex of your minds than a medium through which to exhibit any supposed talent or intelligence of my own. This is precisely my conception of what a people’s organ should be; this was what I saw to be wanting before the Star came into existence”.

What is clear is that the Star was an institution in the everyday life of English workers. As well as meeting to read and educate themselves on its contents, portraits of Chartist heroes printed in the paper would hang in working class homes, or be used to decorate Chartist meeting rooms.

The relationship between the Star and its readers was reciprocal. Chartist readers were not passive recipients of the editorial line, but actively contributed to it.

Rev. Hill remarked that some weeks they would receive enough submissions to fill “six or seven Northern Stars“, often received from workers who had never written for a newspaper or journal before.

Great sacrifices were made by workers to support their paper, James Woodhouse, a knitter and Nottingham delegate to the first Chartist Convention, encouraged workers to:

“Do without your pint of ale, but buy the Star; refrain from drinking spirits, but buy the Star; refrain from using tea and coffee and sugar, but buy the Star..”

O’Connor himself was in no doubt as to the Star’s place in the history of the British working class:

“The first paper ever established in England exclusively for the people… a paper which may be truly called the mental link which binds the industrious classes together; a paper which has, for the first time, concentrated the national mind into one body.”

That the paper didn’t achieve its ultimate goal is here immaterial. The Chartist movement, and papers such as The Northern Star, laid down many of the best traditions of the international workers’ movement. Chartism greatly inspired the works of Marx and Engels.

These great traditions anticipated even greater revolutionary events that were just around the corner. The party of Lenin, and their own revolutionary paper, Iskra, would give them their fullest expression.

Read more about Chartism in ‘Chartist Revolution’, by Rob Sewell, available at Wellred Books.

Other entries in this series: