The American Revolution is known as a revolution of ideas. Intellectual figures like Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin are remembered for their systematic theories about government and its relationship to the people – upholding liberty against tyrannical authority.

But the founding fathers of the United States did not invent these concepts, nor were they really the ones who made the revolution.

As with all revolutions, it was the direct participation of the masses, imbued with revolutionary ideas, that provided the driving force for the upheaval of society.

British colonies

In the case of the British colonies in North America, we have a society that crosses the boundary between the modern and pre-modern world.

Religious and political principles were somewhat mixed together still, but there were also those seeking to separate them and found secular political philosophies based on reason.

Feudal notions of social hierarchy were being confronted with the new spirit of the age, that each man – and yes, it did almost exclusively apply to free white men – can become what he desires, through hard work and enterprise.

The old feudal order of personal privileges was being replaced by the new capitalist order. Initially, many British settlers in the North American colonies were Puritans and other religious dissidents, seeking to escape repression from the Stuart monarchy.

After the British victory over France and Spain in the Seven Years War, Britain’s territories on the continent swelled, leading to an influx of new settlers.

Colonial America was a very literate society, with estimates that 70-90 percent of people were able to read. Much of this came through the Puritan obligation to read the Bible and have respect for independent thought and study.

Literacy was highest in the northern colonies and New England, where Puritanism was dominant and major cities had been established, such as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

These urban areas were to become the hubs of the American Revolution. Here printed books, letters, notices, and pamphlets were commonplace.

The press

Some notable publications include Publick Occurrences, which was suppressed by the British colonial government, and The Boston Gazette, which carried contributions by some famous revolutionaries like Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, and Benjamin Franklin.

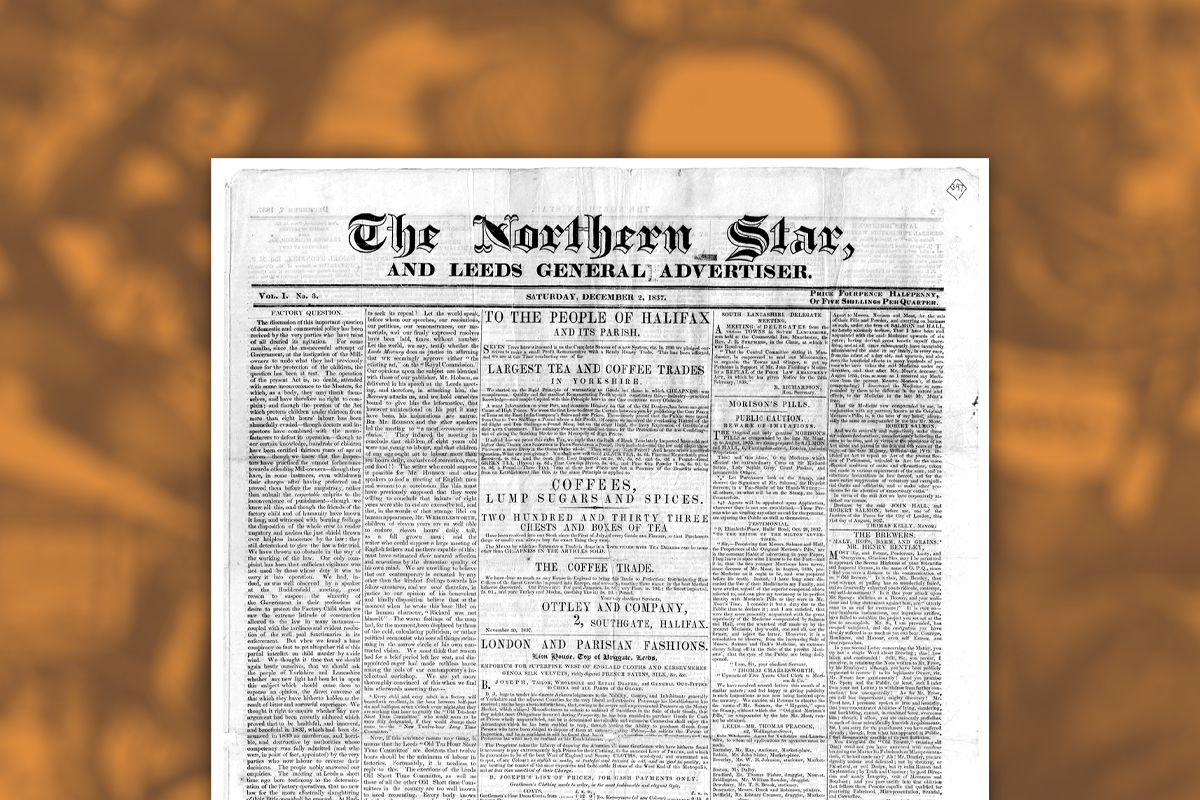

The tradition of publishing broadsides – large, single page newsletters for public distribution, often stuck up in public spaces – ran deep in the major cities. Usually they were the work of individuals, who did the writing, layout, and printing by themselves.

Broadside printing rarely earned much money for the publisher, and so would carry numerous adverts alongside the letters and articles, which were a mixture of fact and opinion.

Very early on, broadsides and small-scale printers became important in the shaping of public opinion in the colonies. Colonial elites would sponsor publications, often to promote their own business interests and campaign for elections.

In all honesty, they were much more like social media trolls of the day than high-quality editorials, often shamelessly slandering their opponents as pimps, drunkards, opium addicts, and adulterers. Our modern gutter press would face stiff competition!

That began to change with the coming of the Revolution, when the press would become a weapon of popular anger and mobilisation, and the disseminator of revolutionary ideas.

Mass movement

Britain’s victory over France in the Seven Years War was extremely expensive. It was perhaps the first truly global conflict that involved all the major powers of Europe, fighting all over the world.

To recoup some of the costs, Britain attempted to raise taxes on the American colonies. This provoked a revolt.

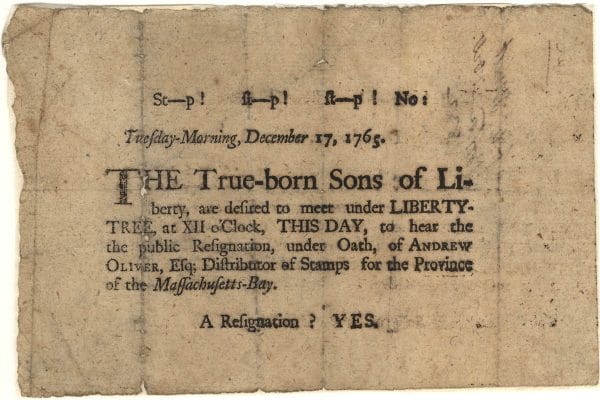

Hated perhaps most of all was the Stamp Act, which required a paid government stamp to be attached to almost any printed document. This hit the broadside printers hard, and drew particular opposition from the American colonial bourgeoisie.

These men, some of whom such as John Hancock were the richest in the land, depended a great deal on ledgers, contracts, inventories and all manner of trade documents.

These magnates, but also more modest men formed the backbone of the Sons of Liberty: a secret brotherhood dedicated to defending the rights of the colonists.

Many were also involved in broader networks of political thinkers and agitators, known as the Committees of Correspondence.

From these organisations – through letters, pamphlets, and flyers connecting with the more plebeian layers of the population – grew a mass movement.

A mass boycott movement against British goods spread in protest against the Stamp Act. In particular, women as the makers and menders of clothing and household goods, were drawn into the movement. Rather than using imported British textiles, they switched to rough ‘homespun’ fabric.

Contrary to some popular myths, the Revolution wasn’t all just a rebellion against taxes. The colonies were also facing an acute economic crisis, causing rising poverty in urban areas and unemployment among the proto-proletarian class that existed around the docks and in the mechanics’ yards.

Other British impositions such as the requirement to provide hospitality to colonial soldiers, and the suspension of the semi-democratic colonial legislatures and town hall meetings also drove widespread opposition.

A decade after the Stamp Act, and widely publicised events such as the infamous Boston Tea Party and the Boston Massacre – word of which spread via flyers and broadsides – the idea of American Independence began to take root, particularly among the lower classes.

We the people

The outstanding figure of this time is Thomas Paine. His pamphlet advocating for independence, Common Sense, remains the most popular title in American history. With around 100,000 copies sold in 1776 alone, practically everyone in colonial America had read it.

He also produced inspiring works such as The American Crisis that intervened at a decisive point in the Revolutionary War, and later his ideas had great influence in the French Revolution of 1789 with The Rights of Man.

Common Sense is exactly as the title implies, a straightforward argument based upon reason and the experiences of the common American to advocate for their political empowerment.

Written in a clear, passionate style, the text was the printed expression of the political aspirations of the masses: for national independence and a radically democratic form of government.

‘Liberty’ was no longer simply the tradition of ‘free-born Englishmen’, but the universal right of all people.

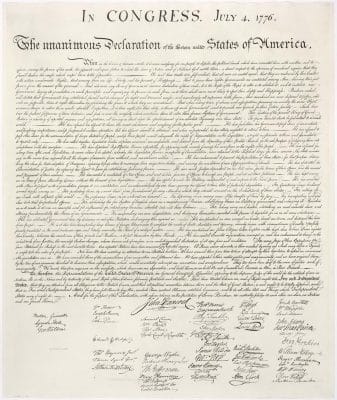

Without Paine, we would probably not have one of the defining phrases of free government that comes from the American Revolution, that opening line of the Declaration of Independence:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

The Declaration itself – hotly debated, and not supported by all the American bourgeois leaders for how radical it was – became a document for mass distribution.

As Alan Woods comments in Marxism and the USA, this document “was a clarion call to the downtrodden and oppressed everywhere. It was as revolutionary in 1776 as The Communist Manifesto would be in 1848.”

After the triumph of the revolution, the hopes of ordinary Americans that a new, more equitable, more free form of government could be established came into conflict with the rights of property.

Popular literature was suppressed and social agitation shut down, as the new bourgeois masters of America consolidated their control on the backs of ‘the People’.

Ultimately, the revolution was fought not to establish liberty and equality for ‘the People’, but freedom for the bourgeoisie and the slave-owning elites. The material basis for a struggle against private property itself did not exist yet.

The struggle of the working class today is to strip these terms of their hypocrisy, to fill them with a real class meaning, and make a new revolution that will truly emancipate humanity.