On 22 February 1848, the Parisian masses rose up and within two days overthrew the July Monarchy of Louis-Philippe.

The revolutionary explosion soon spread like an unstoppable wave across the European continent, sparking a series of insurrections in what is today Germany, Italy, Austria, Hungary and even Romania.

Communist Manifesto

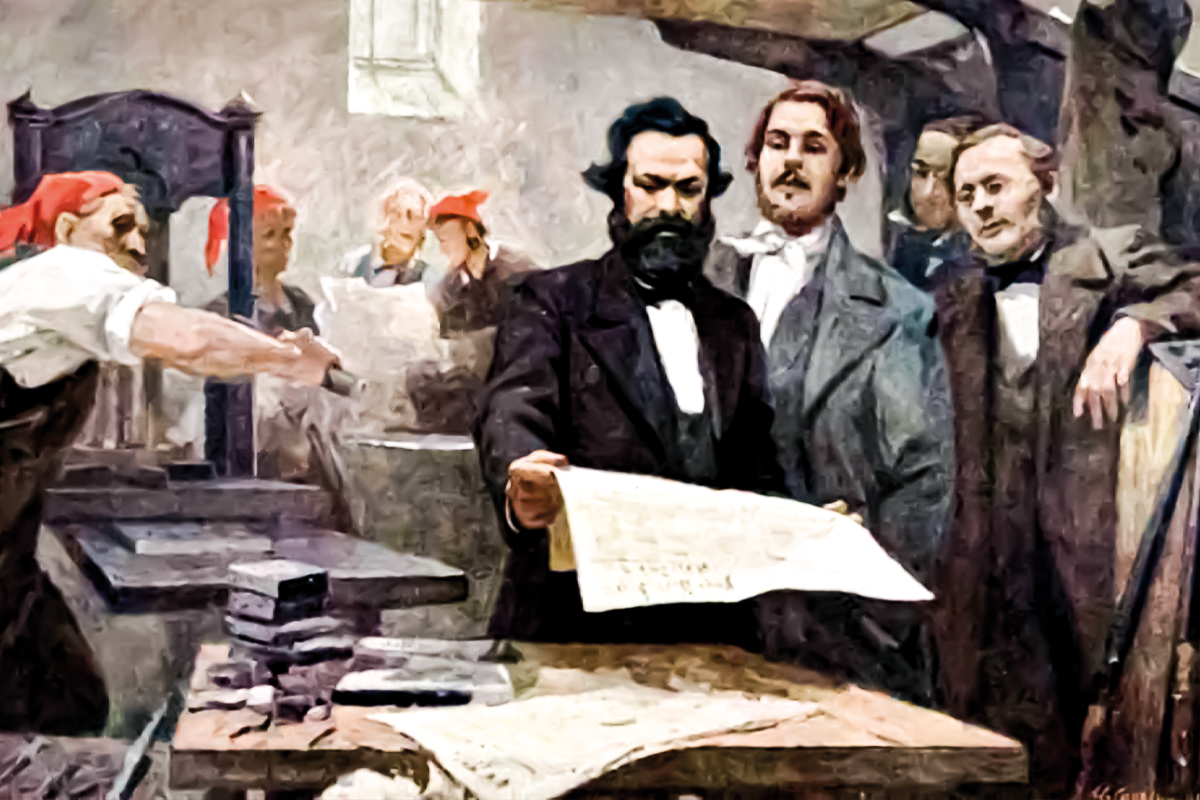

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, young men at the outbreak of the 1848 Revolution, were at the beginning of their long revolutionary careers. The fathers of scientific socialism had only recently thrown themselves into the burgeoning socialist movement.

The year previously they joined the grandiloquently named ‘League of the Just.’ Immediately they had brought sharp political clarity to this eclectic mix of utopians.

In June 1847, their intervention successfully transformed the organisation into the ‘Communist League’ and they were assigned the task of drafting a ‘Communist Manifesto’.

Published in November, this astonishingly far-sighted text served as the ideological bedrock for most advanced elements as they intervened in the maelstrom of 1848.

The Manifesto acted as the foundations – but a building requires much more than that. As the revolutionary wave swept across Europe it became necessary to analyse new developments, to expose the treachery of the bourgeois and point the way forward.

With the March insurrection in Berlin, the revolution had made its way east, and in its trail came Marx and Engels. They made their way to Cologne in the Rhineland, correctly identifying this as the most economically and politically advanced part of Germany.

The Springtime of the Peoples

1 June saw the first edition of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung; right from the outset Marx and Engels used this paper to ruthlessly expose the machinations of the Prussian state.

The first edition began with an attack on the reactionary Prussian state’s attempts to disarm the people.

It should be stated that this was in a period in which the King of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm IV, donned the German tricolour and proclaimed himself at the head of the revolution! This was nothing more than pure demagogy of course, but there existed widespread illusions at the time.

Marx and Engels understood it was better to be in a minority, no matter how tiny, than to capitulate to the pressures of bourgeois public opinion.

They sought to reveal the clearly reactionary role of the Prussian monarchy, and laid bare the treacherous role of the bourgeoisie.

In this, they modified the initial perspectives of the Communist Manifesto that had outlined the need to support the bourgeoisie in its struggle against feudal reaction.

As events unfolded, they came to realise that the bourgeoisie could play no progressive role as it looked to reconcile with the monarchy and aristocracy in fear of the masses.

In a brilliant article titled ‘The Fall of the Camphausen Ministry’, Marx outlined the lamentable role of this liberal-bourgeois government:

“In the service of the big bourgeoisie, it had to cheat the democratic revolution of its fruits; in the struggle with democracy, it had to ally with the aristocratic party and to become the tool of its lust for counterrevolution. The latter is now sufficiently strengthened to be able to throw its protector overboard.”

So profound are many of the insights made by Marx and Engels in these letters that they continue to this day to be a treasure trove of theoretical material.

Marx’s criticism of the vacillating liberals could be written today. We are currently witnessing bourgeois liberals lay the basis for openly reactionary outfits to come to the helm in one country after the next. Starmer/Macron/Biden could be swapped in for Camphausen.

Counterrevolution

The Neue Rheinische Zeitung made many such brilliant theoretical insights, not in the least on the national question, which rose to prominence with the abortive attempts at German and Italian unification and the Hungarian Revolution.

The fundamental Marxist position on the national question can be understood by reading these articles. They supported the revolutionary efforts of unification and independence for Hungary, whilst recognising the reactionary tool of Slavic nationalism as a tool of Habsburg counterrevolution.

The Neue Rheinische Zeitung’s fate was inextricably linked with the fate of the revolution itself. By May 1849 the counterrevolution was in full swing and the King of Prussia had long since cast aside his German tricolour.

As reaction swept Europe, the Prussian state ordered the expulsion of Marx. On May 19 the last issue of Neue Rheinische Zeitung was published in all red ink, and made the famous declaration:

“We have no compassion and we ask no compassion from you. When our turn comes, we shall not make excuses for the terror.”

The paper itself may have been stamped out but the ideas it helped to clarify would go on to arm the working class for the titanic battles to come – not just years later, but decades and centuries.