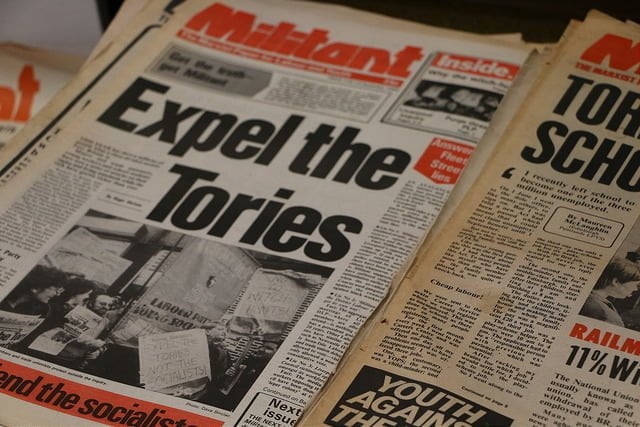

The rise of the Corbyn movement and Momentum – along with recent comments by Tom Watson (the deputy leader of the Labour Party) about Trotskyists and “entryism” in the Labour Party – have resulted in a renewed interest in the mainstream media about the history of the Militant: the Marxist tendency in the labour movement that became a household name in the 1970s and 80s as a result of its bold fight against Thatcher and the Tories.

To set the record straight and explain the lessons for socialists in the Corbyn movement today, we republish here (in two parts) an abridged article from October 2004 by Rob Sewell, the editor of Socialist Appeal and former member of the Militant Editorial Board, who recounts the real history of the Militant.

In this second part, Rob discusses the mistakes made by a section of the Militant leadership, which led to the tendency’s decline.

[Read part one here]

The best traditions of the Militant live on today through the work of Socialist Appeal: the Marxist voice of labour and youth. If you want to help rediscover these revolutionary traditions today, join us in the fight for socialism.

Click here more information about the history of the Militant and Socialist Appeal, or read Alan Woods’ biography of Ted Grant – the founder of the Militant.

Internal problems

Despite these enormous successes, there were serious problems starting to develop within the tendency. Our mass work around the Poll Tax placed colossal pressure on the comrades, especially in the localities, and the burden, which was increasing, was falling on fewer and fewer shoulders. We were beginning to fall victim to the limitations of “single issue” politics and the work was becoming more and more unbalanced. This had very negative consequences.

There were a lot of frustrations at the time. For instance, at a national meeting of regional representatives in September 1990, alarm was raised that the tendency was locked into the Poll Tax struggle, with no time for anything else. It was reported that our full-timers had become anti-Poll Tax full-timers, and our comrades were substituting themselves for the working class. The organisation department was becoming increasingly an anti-Poll Tax department and we were over-stretched and in danger of running the tendency into the ground.

In fact, we had boxed ourselves into a corner. The pressures were bearing down on us from all sides. The tendency seemed to be continually on a war footing, leaping from one action to the next, one court case to the next, and one confrontation with the bailiffs to the next. The problem was that our successes in the Poll Tax campaign went to some comrades’ heads. To use a phrase of Stalin, they were “dizzy with success”.

This was especially the case in Scotland and Liverpool, two areas that were directly under the control of Peter Taaffe. There was a sense of frustration and impatience. At bottom this was a reflection of a low political level, lack of perspectives and lack of a sense of proportion. What was needed was to explain to the comrades the limitations of the Poll Tax campaign and the need for a worked out perspective of how the Tendency would develop, not only today, but also tomorrow and the day after.

Unfortunately, no attempt was made to educate the comrades in this spirit. Instead, the moods of impatience were systematically fed and reinforced from the national centre. The young and inexperienced full-timers were encouraged to put pressure on the comrades to run around and get immediate results. As a result, many older comrades were burnt out and dropped out. This in turn led to a political dilution of the tendency and a further decline of the political level.

The political capital of the tendency was being frittered away for the sake of illusory short-term gains. If the full-timers could not meet the ambitious targets demanded by the Centre, they would just invent spurious results that were passed on to the Centre. There was a growing gap between theory and practice. We were running ever faster in order to stand still. Also, there was increasing substitutionalism, where the full-timers were substituting themselves for the rank and file comrades, who were substituting themselves for the class. One thing led to another, producing a downward spiral. But the leading group paid no attention to this.

The group around Peter Taaffe had lost all sense of proportion. Taaffe by this time had become obsessed with his own importance. He even revealed privately that the fate of the British revolution was on his shoulders alone! The arrogance of the leading circle was transmitted to the rank and file through the full-timers, who lacked the necessary theoretical training that the old layer had had. This increasingly alienated other sections of the Left and ordinary Labour workers. This was of no concern to the group around Peter Taaffe. They seriously imagined that we could somehow by-pass the Labour Party. We could do it all on our own.

There was a big problem for Taaffe: the colossal political and moral authority of Ted Grant. This was the cement that had kept the Tendency together through the most difficult circumstances. It was Ted who worked out the perspectives and he would never tolerate adventures, stunts or ultra-leftism. Politically speaking, Taaffe did not come up to Ted’s ankles, and he knew it. He was always overshadowed by Ted’s political authority, and this continually rankled with him.

Peter was without doubt a capable man, but his abilities were of a purely organisational and agitational character. He was never a theoretician. But he was extremely ambitious and felt his “genius” was not being properly recognised. Unable to tackle Ted in an open political debate, he therefore manoeuvred to isolate him within the leadership. In this he received encouragement by the group of yes-men and women he had gathered around him. The latter owed their promotion to him and were constantly egging him on to sideline Ted.

The tendency, which in the past had prided itself on a strong theoretical foundation, was becoming trapped in a spiral of constant activism. There was no time to draw one’s breath, let alone politically train the comrades in the fundamentals of Marxism. We were building on unsound foundations. The whole edifice was becoming top-heavy. This was to have the most serious consequences.

Ted and Alan Woods attempted to address the problem of the low political level and lack of cadres. Ted had continually warned about the lack of theoretical training of the newer comrades, but was ignored. The fact was that the group around Taaffe were not interested in theory, which they at best regarded as an unnecessary encumbrance, at best as the fairy on the Christmas tree. They treated Ted with complete contempt, although they did not yet dare to attack him publicly.

The other problem they had was Alan Woods who firmly supported Ted and had a lot of support, especially in the tendency internationally. Immediately after his return from Spain, Alan revived the moribund theoretical journal, the Militant International Review (MIR). This was very popular with the rank and file and the full-timers, who keenly felt the need for theory. But the journal was given no support from the leadership, which starved it of resources. At no time was the MIR even discussed on the leading committee.

Eventually, Taaffe managed to remove Alan from the journal, alleging that he was “too busy” with international work. This was entirely phoney. Despite Alan’s very heavy international commitments, he was running the journal very successfully. It was actually coming out regularly, which it never did before and was popular with the comrades. But that was just what Taaffe could not stand. He wanted every aspect of the work to be under the control of people he trusted, irrespective of their personal or political abilities, or the lack of them.

The “Scottish turn”

Impatience in revolutionary politcs plays a pernicious role. Some people, especially in Liverpool and Glasgow, were seeking a shortcut to success. In April 1991, they convinced Taaffe to launch a “new turn” in Scotland, allegedly to combat Scottish nationalism and reap the rewards of the Poll Tax campaign. This was sold to the leadership as a “temporary detour”, nothing out of the ordinary. Of course, it was nothing of the kind, as subsequent developments proved.

The tensions within the leadership had been growing over a long period. They suddenly erupted over a secondary incident early in 1991. A violent argument broke out about Taaffe’s attempts to promote his followers in a blatant way. Ted Grant and Alan Woods accused him of organising a clique – which was perfectly true and evident to anyone who worked at the Centre (the national office). This led to a sharp deterioration in relations within the leadership.

It soon became evident that the Taaffe group had been preparing for this for a long time. They immediately mobilised the full-time apparatus to crush the “disloyal opposition”. They instituted a kind of loyalty oath to isolate their critics, on whom the most extreme pressure was brought to bear. Meetings were organised, not for the sake of debate, but to denounce Ted and Alan. Nobody spoke to the handful of supporters of the opposition at the Centre, not even to say good morning, and all kinds of petty measures were introduced, even to the extent of searching people’s bags before they were allowed to leave the building.

When I saw what was happening, I was shocked. These methods had nothing in common with the clean democratic traditions of the Militant, which we were all so proud of. All kinds of pressures were put on me to fall into line, but I refused. Taaffe even suggested I take a “long holiday”! But it was really impossible to condone what was being done in the name of the Militant Tendency. A stand had to be made, even if we were in a minority – which we were, of course.

The Walton adventure

Soon afterwards, events took a new turn. With the death of Eric Heffer, a Militant supporter, Leslie Mahmood, put her name forward but was manipulated out of the contest. The group around Taaffe suggested standing an independent candidate in Walton. At a staged-managed national meeting held in Liverpool, with Alan away, only Ted and I spoke and voted against the decision to stand. Taaffe and his supporters presented the “Walton turn” as a short cut. Ted aptly described it as “a short cut over a cliff.” Later events showed just how right he was.

At that time, there were a lot of doubts, especially among the more experienced comrades. But there was now no turning back. The leading group had now embarked on an ultra-left adventure with a logic of its own. They irresponsibly decided to sacrifice our members of parliament and deliberately to court expulsion. During the Walton campaign, when Dave Nellist asked if he should support the official Labour candidate in Walton, as all Labour MPs are required to do or face expulsion, he was told by Taaffe, “under no circumstances!” These few words from the General Secretary effectively sealed his fate.

The leading group in Hepscott Road whipped up a campaign that raised entirely false hopes in our prospects of success. Comrades were drafted into Walton from other parts of Britain and even from abroad. But despite all the wild boasts and exaggerated reports, Leslie Mahmood came third with only 2,613 votes, compared to Labour’s 21,317. The Walton episode was a complete farce. But this could not be admitted, because the Leadership had to be infallible. Therefore, on the front page of Militant, a banner heading appeared proclaiming this disastrous result as “2,613 votes for Socialism!”

Of course, anybody can make a mistake. That is not a problem as long as the mistake is honestly admitted and not repeated and the lessons are drawn. That was always the method of Lenin and Trotsky, and it was what Ted had always taught us. For a serious Marxist leadership to admit a mistake is only part of the learning process. But for a leadership that lacks the necessary political and moral authority, mistakes cannot be admitted. In such organisations the leaders can never admit mistakes because they feel that this would undermine their prestige. Consequently the same mistake is repeated over and over again. Then it ceases to be a mistake and becomes a tendency.

The Walton rout caused consternation in the ranks, who had been given to believe that we could win the seat. In a desperate attempt to raise the demoralised spirits of the rank and file comrades, the leading group promptly declared black to be white and a defeat to be a victory. With a straight face, they announced: “This success should be repeated in other parts of the country”!

The Walton episode was a bad mistake, but not necessarily a catastrophe. It could have been corrected. But Taaffe and his group could not do this. The overriding consideration in all this was the prestige of the leadership. Everything else was subordinate. By refusing to admit a mistake, they turned a defeat into a shameful rout that ended in the destruction of the Militant and the work of four decades.

The immediate effect of the Walton adventure was to provide invaluable ammunition to Labour’s right wing, which naturally intensified the witch-hunt. The main victims were the two MPs, Dave Nellist and Terry Fields (tragically, Pat Wall had died by then). Pursuing their irresponsible policy, the leadership had deliberately placed their heads on the chopping block and the right wing had no problem in securing one of their principal objectives:

“On the basis of photographic, and other verifiable evidence of Labour members campaigning for Mahmood in the by-election, the NEC Organization Committee ordered 147 suspected Militant sympathisers to be suspended – the biggest ever crack-down against the organisation”, wrote George Drower. “Proceedings were begun to expel allegedly Militant-supporting Labour MPs, Dave Nellist and Terry Fields.”

It took us decades to build up these positions, but only a few months to throw them away. The sole motive for this was to maintain their prestige. They were blind to all the consequences of their actions. Every lunatic move was one hundred percent correct, and all criticism was regarded as little short of treason.

In the leadership, Ted, Alan and myself opposed the ultra-left “new turn”, which was quickly heading down the same road as the Healyites some thirty years before, and which the Militant had always fought against. The so-called debate on the “turn” was a farce that had nothing in common with our democratic traditions. The opposition was subjected to a vicious campaign of distortion, lies and slander, orchestrated by Hepscott Road. They claimed that we were in favour of our MPs paying the Poll Tax, that we were against action and only wanted to “passively wait upon events”, we wanted a quiet life in Labour Party meetings, etc, etc.

Not a word of this was true. But the rank and file was not in a position to know the facts. The leading group controlled the full-time apparatus and used it in an unscrupulous way to undermine us. The reason for this was that they were completely unable to answer us politically. We were treated, not as erring comrades to be convinced by argument (as had always been our approach to oppositionists in the past), but as enemies. In an atmosphere of hysteria, we were sacked from our jobs and unceremoniously expelled, along with the rest of the opposition.

The heritage we reject…

Over the decade or so following the split, Taaffe and his followers have had a golden opportunity to demonstrate the correctness of their perspectives, policies and methods. When we were expelled, the majority argued that the only thing preventing the meteoric growth of the Tendency was our connection with the Labour Party. All that was necessary was to break from the Labour Party, and we would “grow by leaps and bounds”.

This was said repeatedly (with these very words) in one meeting after another. But as old Engels liked to say, “the proof of the pudding is in the eating.” We are entitled to ask: What is the balance sheet? What has been achieved in the space of over a decade? After all, that is not a negligible period of time. Has the Militant “grown by leaps and bounds”? Nobody believes this! On the contrary, they have succeeded brilliantly only in one thing – in destroying the Militant utterly.

Following the expulsion of the opposition, the Militant tendency immediately went into a steep decline. From 8,000 comrades, which we had at our peak, the Taaffe group were eventually reduced to a rump of a few hundred people. There has been one split after another – an inevitable result of the organizational measures that were first used against the opposition and were later used against anybody who did not support the leadership with sufficient enthusiasm.

The comrades in Liverpool – “the jewel in the crown” of Militant – subsequently came into conflict with the leadership, were suspended, and then expelled, including Dave Cotterill, Taaffe’s main supporter on Merseyside, who he used to praise in glowing terms. The organisation that led the 1983-87 struggle was utterly wrecked. In Scotland – as we predicted – Tommy Sheridan and practically the entire organisation parted company with Taaffe and have now moved away from Marxism and towards left nationalism.

Living in their ultra-left dream world, the Taaffe group really imagined that they were going to replace the Labour Party. They launched the so-called “Socialist Party” (one of about twenty or so that one can choose from) that has been a spectacular flop. They regularly stand in elections and regularly obtain derisory results, which are regularly proclaimed as great victories for socialism.

After the split they fell over themselves in their haste to jettison all the old ideas, methods and traditions that had been proved to be successful, not in demagogic speeches but in fact. Now in their sectarian madness they declare that the Labour Party is a bourgeois party and call on the unions to disaffiliate from Labour. This has nothing in common with the methods and traditions of Militant but is more like a caricature of the Third Period policies of the Stalinists. Like all the ultra-left adventures of the past, it will lead nowhere.

In order to solve their financial problems they had to sell off the big headquarters in Hepscott Road – a great achievement to which we all contributed but which they managed to lose all on their own. The money they got from the sale will keep them going for a while, but it will not last forever. And in any case, no amount of money can make up for the lack of correct ideas, perspectives, policies and methods.

As a final indignity, they even jettisoned the name of the Militant. This was an act of sheer stupidity. The name of the Militant was known not just in Britain but also all over the world. But nobody has heard of the paper of the “Socialist Party”. Even the bourgeois understands that a successful brand name ought not to be abandoned.

In this way, not a single trace is left of what we built. One by one they threw away all the gains we had made with such difficulty and sacrifice in the past. This is a result that not even the most optimistic of our enemies could have anticipated! He who is not capable of defending the gains of the past will never be able to lead the way to future advances. Peter Taaffe has earned his place in the history books, but not in the way he had hoped. He will be remembered as the man who destroyed the Militant.

And the heritage we defend

Our success in Britain was an historical breakthrough with no parallels in the history of the movement. Today it is necessary to spell out the reasons for this remarkable success so that the new generation can learn from it and benefit by it. The spectacular rise of Militant was the result on the one hand of a scrupulous attitude to ideas and Marxist theory and on the other to the fact that we did not succumb to ultra-leftism and sank deep roots in the Labour Movement.

Our success in Britain was an historical breakthrough with no parallels in the history of the movement. Today it is necessary to spell out the reasons for this remarkable success so that the new generation can learn from it and benefit by it. The spectacular rise of Militant was the result on the one hand of a scrupulous attitude to ideas and Marxist theory and on the other to the fact that we did not succumb to ultra-leftism and sank deep roots in the Labour Movement.

We remained within the Labour Party while all the others marched off into the wilderness, where they stagnated and declined. The Militant, on the other hand, did in fact grow by leaps and bounds, thanks to a correct policy. Our orientation to the mass organisations, and especially the Labour Party, was the key factor in this process. That we were highly successful is clear in the first place from the reaction of the ruling class to us.

The attack on Militant was really the first step in a sustained and orchestrated offensive against the left wing of the Labour Party and was part of an attempt on the part of the ruling class to regain control over the Labour leadership and turn it into a tool in its hands. This ended in the temporary aberration of Blairism and so-called “New Labour”. But the struggle for the Labour Party is by no means over. In fact, it has scarcely begun.

The Blairite right is now on the defensive. The opposition of the rank and file is growing. People are looking for an alternative, but not outside the Labour Party. If we had succeeded in keeping our forces together, building on the gains of the past, we would now be in a much stronger position to take advantage of the big possibilities that will open up in the next period when Blair is forced out and the fight in the Labour Party begins in earnest.

It is a matter of regret that many of the positions we won through hard work were criminally thrown away, and that many good cadres were destroyed in the process. Things would have been a lot easier than they are. But the struggle continues anyway. The basic nucleus of the forces of Marxism remain intact and are continuing to work, to fight, to win new friends and supporters and to advance. In fact, we have been strengthened, not weakened, by ridding ourselves of sectarian and ultra-left elements.

The argument that the demise of Militant was due to difficult objective conditions is radically false. Ted always points out that good leadership in a period of retreat is even more important than when you are advancing. The difference is that with good generals you can retreat in good order, keeping your forces intact and preparing for a new advance when conditions are ripe for it. But bad generals will always turn a retreat into a rout. That is just what happened.

Today we pay tribute to the great achievements of the past. We are proud of the traditions of Militant, which we are still continuing to this day. The real inheritor of Militant is the Marxist tendency that is fighting for socialism in Britain and internationally – the tendency of Ted Grant, represented by Socialist Appeal and the International Marxist Tendency. We proved before how a successful Marxist tendency could be built by combining the ideas of Marxism with the mass organisations of the working class, and we will do so again.