The rise of the Corbyn movement and Momentum – along with recent comments by Tom Watson (the deputy leader of the Labour Party) about Trotskyists and “entryism” in the Labour Party – have resulted in a renewed interest in the mainstream media about the history of the Militant: the Marxist tendency in the labour movement that became a household name in the 1970s and 80s as a result of its bold fight against Thatcher and the Tories.

To set the record straight and explain the lessons for socialists in the Corbyn movement today, we republish here (in two parts) an abridged article from October 2004 by Rob Sewell, the editor of Socialist Appeal and former member of the Militant Editorial Board, who recounts the real history of the Militant.

In this first part, Rob discusses the growing influence of the Militant and the attempts of the Labour bureaucracy to expel Militant supporters from the Labour Party.

The best traditions of the Militant live on today through the work of Socialist Appeal: the Marxist voice of labour and youth. If you want to help rediscover these revolutionary traditions today, join us in the fight for socialism.

Click here more information about the history of the Militant and Socialist Appeal, or read Alan Woods’ biography of Ted Grant – the founder of the Militant.

From a miniscule group with no resources, the Militant became the most successful Trotskyist tendency in Britain since the founding of Trotsky’s Left Opposition. Unfortunately the majority of its leadership was to take an ultra-left turn that would eventually destroy it.

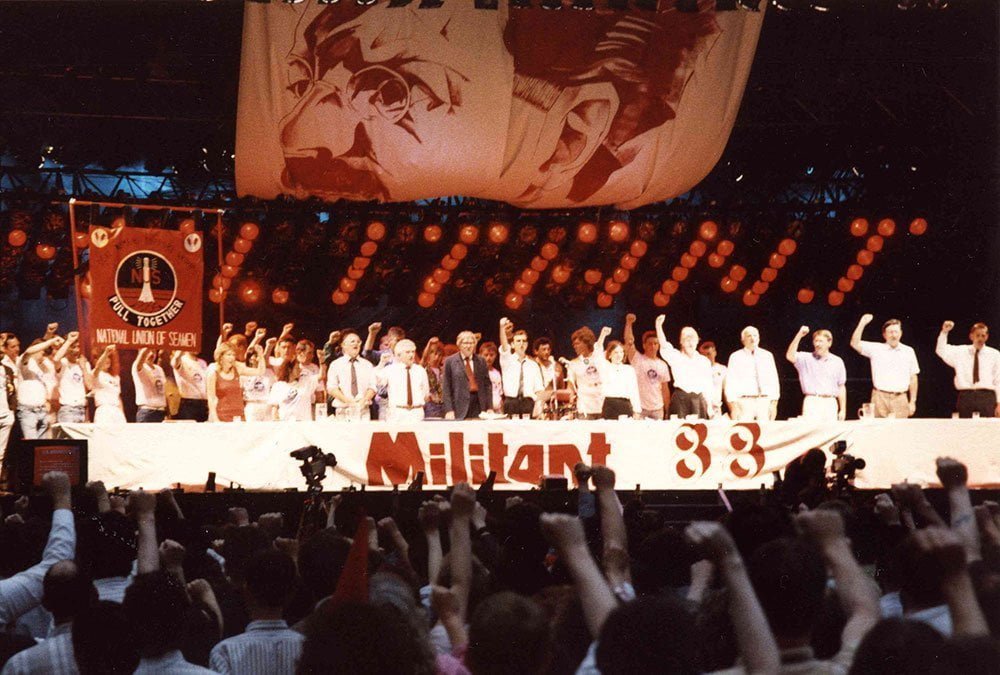

At its height in the late 1980s, Militant became a household name. Everybody knew about the Militant Tendency, not just in Britain but internationally. We controlled the Labour Party Young Socialists, had a growing influence within the Labour Party and trade unions, had more than fifty councillors, three Members of Parliament, a comrade on the National Executive Committee of the Party, as well as a member on the General Council of the TUC. We led the Liverpool City Council in battle with the Tory government and also the multi-million strong anti-Poll Tax Campaign, which eventually brought down Thatcher.

These were extraordinary achievements by what started as a very small group. In 1988, the Tendency had more than 8,000 supporters, national and regional headquarters, as well as 200 full-time workers – even more than the Labour Party. Investigative journalist Michael Crick described the Militant as Britain’s fifth largest political party. This was not far from the truth.

As a consequence of our success, we attracted the fierce opposition from the ruling class and its right wing agents within the Labour movement, which instigated the biggest witch-hunt against the supporters of Marxism since the 1920s. Militant’s growing influence in the Labour Party was considered by the strategists of Capital as the most dangerous to the capitalist system.

The ruling class ignored (and still ignores) the sectarian splinter groups on the fringes of the Labour Movement – but this they could not ignore. In the end, however, Militant was destroyed from within, as a result of the mistaken perspectives and policies adopted by a part of the leadership. It is imperative that we learn the lessons from this, because he who does not learn from history will always be doomed to repeat it.

Modest beginnings

Yet Militant had an extremely modest beginning. It started as a monthly with a few pounds in the bank, a typewriter, a shared office and no full-time staff. But we had something far more important than money and material resources. We had ideas, perspectives and policies, and we pursued the correct methods and were firmly rooted in the mass organizations of the working class. This was guaranteed above all by Ted Grant, the founder and inspirer of Militant and the architect of all its successes.

Yet Militant had an extremely modest beginning. It started as a monthly with a few pounds in the bank, a typewriter, a shared office and no full-time staff. But we had something far more important than money and material resources. We had ideas, perspectives and policies, and we pursued the correct methods and were firmly rooted in the mass organizations of the working class. This was guaranteed above all by Ted Grant, the founder and inspirer of Militant and the architect of all its successes.

Ted was the founder and leading theoretician of the Workers’ International League and then the Revolutionary Communist Party. With the break up of the RCP in 1949, a small group joined the Labour Party and published a magazine called International Socialist, and later the Socialist Fight, both edited by Ted. (See Ted Grant, History of British Trotskyism).

The main task in these years was to defend the programme, theory, traditions and methods of genuine Marxism, or Trotskyism, against opportunism and ultra-leftism.

Militant launched

The decision was taken in the summer of 1964 not to revive Socialist Fight, but to launch a new paper aimed at the Labour youth. As always in any new venture lively debate takes place over the name for the new paper. But the choice is limited given other competitors. Eventually, the name Militant was chosen, with the paper’s masthead “For Labour and Youth”, with the launch date of October 1964. The first editorial explained:

“The job is to carry the message of Marxism to the ranks of the Labour movement and to its young people. There is room for all tendencies in the Labour movement including the revolutionary Left.

“Above all, the task is to gather together the most conscious elements in the Labour movement to patiently explain the need for these policies on the basis of experience and events. Militant will endeavour to seriously gather the facts and arguments to provide the ammunition for this struggle to rearm the Labour movement. Soberly we hope to present a Marxist analysis, whether of industrial disputes, the housing crisis, or the crisis in the Congo, to take a few examples at random, with suggested solutions in the interests of the working class. The most important thing is that we wish to tell the truth to the working class, against the lies and exaggerations of the capitalist class and the half truths of Labour’s officialdom.”

Apart from insisting on the central role of theory and cadre building, Ted ensured that the paper’s orientation would be firmly towards the mass organisations, particularly the Labour Party and the trade unions. He insisted that we should avoid the shrill ultra-leftism of the sects and argue the Marxist case in a sober fashion, sticking to “facts, figures and arguments”. Without making any principled concessions, the paper expressed the ideas of Marxism in a language that would be understood by Labour Party members, trade unionists and youth. In the words of Lenin, our slogan was to “patiently explain” the fundamental ideas and tasks facing the Labour movement.

Foresight and astonishment

Trotsky said that theory is the superiority of foresight over astonishment. The ultra-left groups that left the Labour Party had no theory and no perspective, and were consequently left with their mouths open when the situation changed, which we knew it would.

Trotsky said that theory is the superiority of foresight over astonishment. The ultra-left groups that left the Labour Party had no theory and no perspective, and were consequently left with their mouths open when the situation changed, which we knew it would.

As always in Britain, the transformation of the Labour Movement began in the trade unions. The shift to the left in the trade unions resulted in the election of Jack Jones as general secretary of the TGWU and Hugh Scanlon as general sectary of the AEU. The groundswell from below pushed the TUC into opposition to the Heath government, especially over its anti-trade union legislation. This fight against the government reached its height in 1972 with the arrest of five dockers and the threat of the TUC to call a 24-hour general strike.

As we explained many times, the mass organisations do not develop in a straight line, but dialectically. The organic link between the trade unions and the Labour Party, which Gaitskell and Blair have attempted to break, results in their radicalisation as the masses begin to move. The growing industrial militancy was feeding into the unions and the Party, resulting in a pronounced shift to the left in the Labour Party, even at the level of the NEC.

The shift to the left in the unions was followed by a shift to the left in the Labour Party. Tony Benn, who had formerly been, if anything, to the right of centre in the Party during the Wilson government, now came forward as the leader of the Left. This was no accident, but flowed from the objective pressures that were driving the process.

We can add that our comrade on the NEC played an important role in stiffening the Lefts. Under our influence in 1973, Labour’s NEC came out with the programme of nationalising the top 25 monopolies. Of course, it is necessary to understand the limitations of resolutions, but it was certainly symptomatic both of a sharp turn to the left and of the growth of our influence in the Labour Party.

The first signs of a recovery could be seen in the youth. The Labour Party youth organisation had been at a very low ebb. Now, with Militant playing a leading role in Labour’s youth organisation, all that changed. The Labour Party Young Socialists (LPYS) and Militant began to take on flesh during these years. This rapid progress was no accident but the result of years and decades of patient work, correct programme, perspectives and methods. Attendances at the YS conferences, which had around 200 attending in the late 1960s, began to reach the 1,000 mark. Our Militant fringe meetings also began to attract larger audiences.

Under our direction, the YS took up the struggle against unemployment, racism, and international solidarity. Campaigns were launched on Ireland, Chile, Spain, and other issues. The Spanish Young Socialist Defence Campaign was a great success, raising solidarity with the underground against General Franco.

The second national miners’ strike in early 1974 succeeded for the first time in bringing down a government. Our comrades, especially using the banner of the LPYS, played an important role in the election of a new Labour government. In particular, we helped to secure the election of Tony Benn in Bristol, when busloads of YS members helped in mass canvasses around the constituency. I remember we brought two coachloads of miners from South Wales. That was the extent of the influence we had built up.

Counter-reforms

Faced with a massive revolt on the industrial plane, the Tory government of Edward Heath collapsed in 1974 and was replaced by a new Labour government. Under the impact of the world crisis, the Wilson government shifted from reforms to counter-reforms. The trade union leaders agreed to a wages policy, which began to undermine living standards. By 1977 and the first firefighters’ strike, the dam started to burst. Opposition to wage restraint surfaced within the unions and the Labour party. Wilson was demoralised and resigned, handing the leadership over to Jim Callaghan.

Millions of low-paid workers became unionised and waged a fierce battle for increased wages. They could not wait any longer! Thus began the Winter of Discontent and the demise of the Callaghan government. In 1978, Terry Duffy, a comrade from Liverpool Wavertree CLP successfully moved a composite at the Labour Party conference in opposition to the government’s wage restraint. It was the end of the incomes policy.

The crisis of the Wilson/Callaghan government of 1974-79 enabled the Tendency to connect with a wide layer of radicalised workers as never before. In 1975 we were in a position to take on a new larger industrial premises at Mentmore Terrace in Hackney. By 1976, our supporters had reached the 1,000 mark. Militant’s influence continued to increase. The size of the paper increased to 16 pages weekly.

By this time our success began to attract attention. Alarm bells were beginning to ring, not only in the ears of the Labour bureaucracy, but also in the ruling class. The strategists of Capital were alarmed by the shift to the left in the Labour Party and saw us as a catalyst for this development. For the first time, Trotskyism in Britain had become a serious factor in the calculations of the state.

As early as 1976, a witch-hunt had been started against us with an “exposure” in The Observer newspaper. This used material gathered by Reg Underhill, the Party’s National Organiser to prove a “conspiracy” and instigate a purge against the Marxists. A year later, with the appointment of YS chairman Andy Bevan as National Youth Officer, all hell broke loose in the press about the Militant. The de-selection of Labour MP Reg Prentice in Newham, who later joined the Tories, added fuel to the flames of the witch-hunt against the Tendency.

However, the witch-hunt failed in its objectives. In fact, it was counterproductive. The more publicity given in the media against Militant, the more we attracted support from youth and trade unionists. By the general election of 1979, we had at least 1,500 active supporters in Britain and were very well known in the Labour movement, where our actual periphery was much bigger and growing all the time.

Ruling class alarmed

The defeat of Callaghan and the victory of Margaret Thatcher created a shock wave throughout the movement. It shifted the Labour Party further to the left. Under the leadership of Tony Benn and Eric Heffer, Left reformism became the dominant trend in the Labour party at this time. Even in the Parliamentary Labour Party the right wing was in retreat. Denis Healey, the right wing candidate, only managed to beat Tony Benn by less than one percent! Under these conditions, the Tendency grew by leaps and bounds, breaking through the 2,500 barrier.

The ruling class was now thoroughly alarmed. They could not tolerate a Labour Party under the control of the Left, let alone the Marxists. They organised the splitting away of an important section of the right wing leaders to form the SDP (Social Democratic Party), an attempt to stab the Party in the back. But this backfired. The split of the SDP proved sufficient to keep Labour out of office, but it did not halt the party’s swing to the left. Getting rid of the most corrupt right wing leaders, only served to further intensify the swing to the Left.

All the forces of the Old Order were now mustered to smash the Left, starting with the Militant Tendency. They recognized our role in stiffening the left reformist leaders and so began their offensive against the Left with a furious attack on Militant. The capitalist press was thrown into a frenzy over “Marxist revolutionaries intent on taking over the Labour Party”.

Day in, and day out, they launched a Niagara of lies against “the cancer of Militant”, demanding that we be expelled along with the supporters of the Labour Left led by Tony Benn. As a supplement to the public witch-hunt against the Tendency, it was subsequently revealed that MI5 quietly planted 30 secret agents within our ranks to combat “Marxist subversion”. Here was the real conspiracy against Labour – a conspiracy not by the Left and the Militant Tendency, but by the bourgeois state and its creatures inside the Labour Party, conspiring to take it over and turn it into an obedient tool of Big Business.

The capitalist counter-offensive gave backbone to the right wing in the Labour Party and trade unions. The Underhill Report had been repeatedly blocked by the Left majority on the NEC since it had first been raised in November 1975. However, when Michael Foot became leader and the NEC swung back to the right in 1981, wheels were set in motion for a purge.

Under the remorseless pressure of the bourgeois media, the right wing demanded action on the Underhill Report and the expulsion of Militant. Despite all the resolutions of protest to the NEC, the ‘soft Left’ capitulated, and an “investigation” was narrowly agreed into the tendency by 10 votes to 9. The Haywood-Hughes Report, as it became known, was endorsed by the 1982 Labour Conference, and established a register of “acceptable groups”, from which Militant was specifically excluded.

The fight against the witch-hunt

There have always been Marxists in the Labour Party ever since it was set up. Therefore the attempt to expel the Marxists was in reality an assault on internal Party democracy. The capitalist class wished to reassert its control over the Labour Party by attacking the Left and installing its own trusted agents in the Labour leadership. What they really objected to was that the Militant was so successful and had consistently defeated the right wing. That is why they attacked us so ferociously.

There have always been Marxists in the Labour Party ever since it was set up. Therefore the attempt to expel the Marxists was in reality an assault on internal Party democracy. The capitalist class wished to reassert its control over the Labour Party by attacking the Left and installing its own trusted agents in the Labour leadership. What they really objected to was that the Militant was so successful and had consistently defeated the right wing. That is why they attacked us so ferociously.

The argument that we were organised was just a smoke screen, since the right wing was always organised like a party within a party. That was true of the SPD before they split and betrayed the Labour Party, and it remains true today of the Blairite clique that has hijacked the Labour Party with the enthusiastic support of the same capitalist newspapers that viciously witch-hunted the Militant.

Naturally we defended ourselves against these attacks. In order to defeat the right wing, which had behind it not only the powerful apparatus of the Labour Party but also all the vast resources of the capitalist state, it was absolutely necessary to be organised! We organised a successful anti-witch-hunt Labour movement conference at the Wembley Conference Centre attended by 2,000 delegates. Meetings of 1,000 and more were organized in the major cities of Manchester, Liverpool, Newcastle and Glasgow.

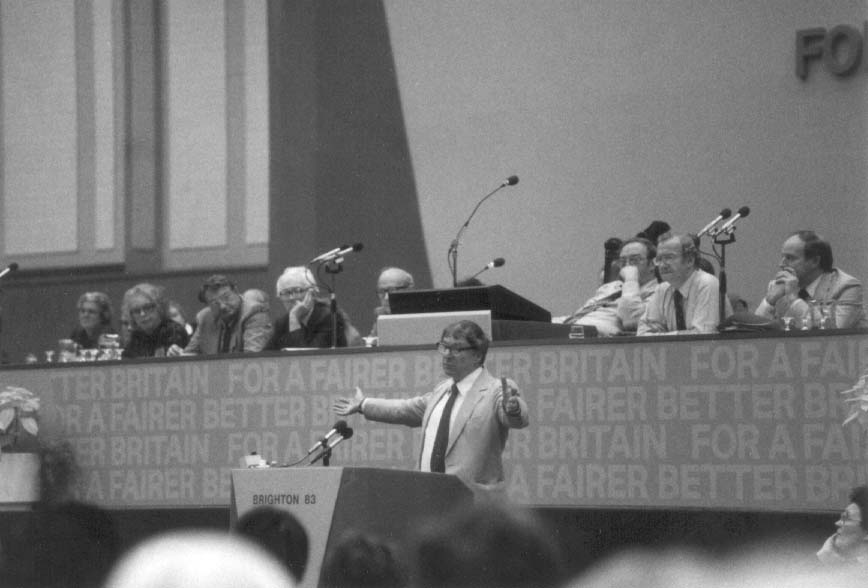

The support for Militant rocketed, with nearly 3,500 supporters recorded in 1982. More and more were attracted to our fight within the Labour Party and our call for socialist policies in the interests of the working class. Despite the fact that the big majority of the rank and file was opposed to expulsions, the NEC proceeded to expel the five members of the Militant Editorial Board in February 1983, on the eve of the Bermondsey by-election.

They argued that by cutting the head off, the body would wither. But that was not true. By this time the Militant had thousands of active supporters and tens of thousands of sympathisers. In order to drive it out of the Party, they would have to destroy Party organisations up and down the country and inflict terrible damage on it, demoralising the activists and making a Labour victory impossible for a long time. This is what actually happened.

The defeat of Michael Foot in the 1983 general election and the election of Kinnock as Labour leader signalled a shift to the right within the leadership. The witch-hunt continued under Kinnock’s leadership. The new Labour leader was completely obsessed with the fight against Militant, which he pursued with fanatical zeal, even though it was doing tremendous damage to the Party. This foolish parvenu slavishly followed the advice of the Tory press that was constantly egging him on. As a result, the rank and file were demoralised and Labour was unable to defeat the Tories.

Despite everything, the general election resulted in the election of two Militant supporters, Terry Fields and Dave Nellist, giving Militant for the first time a voice in Parliament. Unfortunately, Pat Wall failed in his election bid in Bradford North, with the SDP splitting the vote. This was rectified at the 1987 general election, when he was finally elected. For the first time in history, there were Trotskyist MPs in the British House of Commons. Here again was confirmation of our correct approach.

Liverpool City Council

In the same year, Militant hit the national headlines over its role in the leadership of Liverpool City Council. In May 1983, a number of Militant supporters had been elected as Labour councillors. In victorious city elections, Labour gained 12 seats from the Liberals and one from the SDP, while its vote increased by 40%. “I am disappointed for the city. Many members of the Militant Tendency have been elected”, lamented Sir Trevor Jones, the Liberal leader.

In the same year, Militant hit the national headlines over its role in the leadership of Liverpool City Council. In May 1983, a number of Militant supporters had been elected as Labour councillors. In victorious city elections, Labour gained 12 seats from the Liberals and one from the SDP, while its vote increased by 40%. “I am disappointed for the city. Many members of the Militant Tendency have been elected”, lamented Sir Trevor Jones, the Liberal leader.

The success of Militant in Liverpool, like all our other successes, did not drop from the clouds. It was the result of decades of consistent Labour Party work by Jimmy Deane and the Deane family, Tommy Birchall, Pat Wall and others, on whose shoulders the then generation stood. They fought against the Braddock machine that ruled Liverpool with an iron hand, confident that events would transform the situation, which they did in the end. Walton CLP, in particular, was the bedrock for the Tendency for decades. It even chose Ted Grant as their prospective parliamentary candidate in the mid-1950s. Eric Heffer finally won the seat for Labour in 1964.

A Militant supporter, Derek Hatton, was elected Deputy Leader of the Council. With a majority of three, and a dire financial position, Liverpool Labour was faced with a stark choice: either make cuts or fight. To remain within the Liberal-Tory budget would mean abandoning its programme of creating 1,000 new jobs, reducing rents by £2 a week, raising the minimum wage and introducing a 35 hour week for council workers.

Of course, we decided to fight. A massive campaign, involving rallies, public meetings, demonstrations and strike action, was then launched to win support for the council’s stand and fight the Tory’s financial constraints. Eventually the council set a deficit budget, demanding that the Tory government make up the difference.

Despite the ambivalence and opposition of the national Labour leadership, the Liverpool working class rallied to the fight. This was reflected in the May 1984 local elections where Labour’s majority shot up to 17 seats. Eventually, the Militant-led City Council managed to force major concessions out of the Tories, which allowed them to carry through their programme.

“Today in Liverpool, municipal militancy is vindicated”, stated The Times (11th July 1984), “… a third rate provincial politician, a self-publicizing revolutionary… Mr. Derek Hatton has made the government give way… Mr. Hatton and his colleagues threatened a course of disruptive action. The reward is the abrogation of financial targets which 400 other local authorities have been told are immutable… in order to buy off Militant.”

The Militant comrades led the struggle to defend the workers of Liverpool for the next three years until they were surcharged and removed from office by unelected judges. Until that time they won every election contested. At the 1985 Labour Party conference, Kinnock launched a vitriolic attack on Militant and the Liverpool City Council, opening up the purge against all Militant supporters. In November the Liverpool District Labour Party was suspended. “I want them out of the Labour Party”, snarled Kinnock.

The Liverpool comrades, with the backing of the Militant nationally, put up a tremendous fight, but in the end they could not win against the combined hostility of the Thatcher government, the Tory press, the trade union bureaucracy and, above all, Kinnock and the right wing Labour leaders who were determined to see them defeated and thrown to the wolves.

So-called Lefts like “Red” Ken Livingstone and Blunkett also played a pernicious role. Despite all their demagogic speeches and gestures, they left Liverpool in the lurch, isolated and therefore doomed to defeat. Finally, Kinnock put the knife in. Sixteen Liverpool comrades, including Hatton, were charged in March 1986 with “engaging in course of action prejudicial to the Party”, and expelled from the Labour Party in a kangaroo court.

In spite of this, we were not dismayed. We were getting enormous sympathy and support from the Labour rank and file. At the same time that Kinnock was expelling the Liverpool comrades, we organized a 5,000-strong 21st anniversary rally in the Royal Albert Hall, raising a massive £27,000 for the Militant fighting fund.

Successes

I first met Ted Grant in July 1966 at a YS summer school in Swansea, and joined the tendency soon afterwards at the age of 14. In the early 1970s, I was elected to the National Committee of the LPYS and then onto the leadership of Militant. I worked as the West Wales full-timer until the end of 1982, then went to work in the national Centre.

I first met Ted Grant in July 1966 at a YS summer school in Swansea, and joined the tendency soon afterwards at the age of 14. In the early 1970s, I was elected to the National Committee of the LPYS and then onto the leadership of Militant. I worked as the West Wales full-timer until the end of 1982, then went to work in the national Centre.

Towards the end of 1983, I was made National Organiser for the Tendency and made responsible, as head of the Organisation Department, for co-ordinating our response to the witch-hunt and the building of the tendency in the different fields. By this time we had around 200 full-time workers at the Centre and in the areas. It was a very large operation, which was increasing at every turn. Far from declining, the Militant was very much on the advance at this time. We were able to buy a large factory at Hepscott Road in the East End of London, where at least a hundred full-timers were based.

During a part of the struggle in Liverpool (for one year), Britain had been shaken by the miners’ strike. The Tendency was able to put a number of full-time workers into the coalfields to assist the strike. As a result of this work, our authority was enormously boosted with the strikers and some 500 miners actually joined the Militant, although inevitably with the defeat and closures, many dropped by the wayside later. We knew, given our prominence, that we were under close scrutiny by the secret services and made plans in case the national headquarters were raided, the press seized and comrades arrested.

As a result of the witch-hunt against Militant, the coverage on the TV and the newspapers was at saturation point. Every morning I would get photocopies of all the coverage, which stretched across the room in boxes. To capitalise upon this, we organized meetings against the attacks up and down the country, gathering streams of new supporters in the process. By 1987, the list of firm Militant supporters went over 8,000.

Were these lists exaggerated? All I can say is that in that year well over 7,000 people attended our massive rally at the Alexandra Palace in London, with a live link up to hear Trotsky’s grandson, Esteban Volkov, in Mexico City. This was the last national rally before the split that destroyed the Militant.

Despite the witch-hunt, with around 220 being expelled from the party and a layer also suspended from party membership, the ranks of the Tendency remained overwhelmingly intact and rooted to the Labour Party. Of course we expected to be witch-hunted, how could it be otherwise? The point was not to lose our head. Unfortunately, this is just what a section of the leadership did.

The Poll Tax

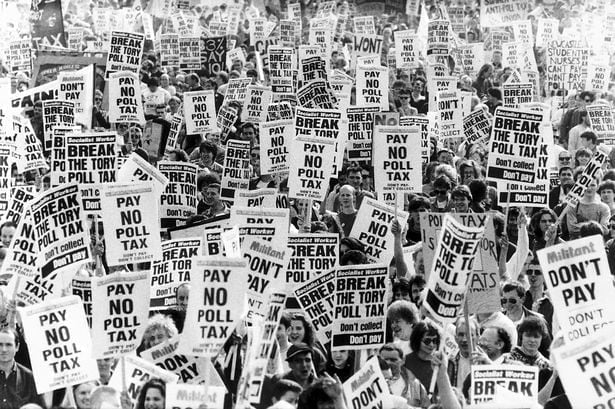

The victory of the Tories in 1987 brought new challenges. Thatcher had promised to introduce a Community Charge or Poll Tax, as it became universally known and hated. The plan was to introduce the Poll Tax in Scotland in the first year, to be followed by England and Wales. Once the Scots had been subdued, the rest would fall into line.

The victory of the Tories in 1987 brought new challenges. Thatcher had promised to introduce a Community Charge or Poll Tax, as it became universally known and hated. The plan was to introduce the Poll Tax in Scotland in the first year, to be followed by England and Wales. Once the Scots had been subdued, the rest would fall into line.

At a series of national meetings soon after the election, Ted Grant outlined the perspectives facing the tendency and for the first time raised the idea of a campaign of mass non-payment “as in Glasgow in the rent strike of 1915” and predicted social upheavals. From then on preparations were made by the Tendency to take on the Tory government.

As people began to realise the massive bills they faced, a burning anger built up in all areas of Scotland. We began mass work by organizing meetings on the schemes (housing estates) and then establishing Anti-Poll Tax Committees made up of local representatives. Within a year, one million people in Scotland were refusing to pay the tax. Tommy Sheridan, who was our candidate to lead the campaign, became the chairman of the Scottish Anti-Poll Tax Federation.

In the meantime, the Labour leaders ran a mile from breaking the law. “The mass non-payment campaign is being led by supporters of the Militant tendency largely because of the political vacuum left by the party leadership”, commented the Scotland on Sunday. “The substantial support to the calls for non-payment is known to be more than an irritant to Labour’s leaders.” (2 July 1989).

I was put in charge, as head of the organisation department at Militant HQ, of co-ordinating the mass campaign throughout the country. The tendency issued two pamphlets on the Poll Tax, both written by myself, which sold in their thousands. The first pamphlet analysed the lessons of the Scottish non-payment campaign, while the second, issued later, dealt with the unfolding struggle in England and Wales.

On the day of the introduction of the Poll Tax in England and Wales, the Militant-led All Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation organised a massive 250,000 strong demonstration in London and a demonstration of 50,000 in Glasgow. Typically, Kinnock disowned 31 Labour MPs who were refusing to pay their Poll Tax. By the end of 1990, some 18 million people were refusing to pay the Poll Tax and Thatcher, discredited, was forced to resign and the tax was effectively scrapped.