This year marks the 60th anniversary of Britain’s first migrant-led strike: an inspiring yet relatively forgotten – but all the more inspiring – three-week event that took place at the Preston Courtauld’s Red Scar Mill in the North West of England.

The Lancashire Evening Post expressed the sentiments of the ruling class at the time:

“The news of the strike has travelled around the world…Preston has become infamous as the centre of futile struggle, which could inflame feelings where whites and coloured coincide.”

Without precedent, the migrant workers independently and determinedly fought back against the attacks on their wages and conditions by factory owners Courtaulds – one of the four major monopolies in man-made fibre in Europe.

In attempting to organise themselves, the migrant-worker strikers faced racism not only from the bosses, but also from within the union itself.

Preston in the 1960s

In the postwar period, mill towns such as Preston, Blackburn, and Bolton received a large number of migrant workers from the Commonwealth, who had headed the call from the Labour government to help rebuild Britain.

For the bosses in these towns, this migration provided fresh exploitable labour.

The Red Scar Mill’s labour officer paternalistically summed up the view of the bosses, stating: “They are gentle folk, on the whole, and are good workers when they wish to work.”

By 1965, the economic situation was still relatively prosperous, with secure employment, contracts, decent wages, and a welfare state. Harold Macmillan’s remark that the nation had “never had it so good” still rang loudly.

Cracks were beginning to show, however, as the economy began to slow down. In 1962, the Conservative government legislated the Commonwealth Immigrants Act – the first limitation of migration to Britain since 1948.

Upon its introduction, the Labour Party deemed the act as “cruel and brutal anti-colour legislation”. By 1968, though, Harold Wilson’s government was further widening the act.

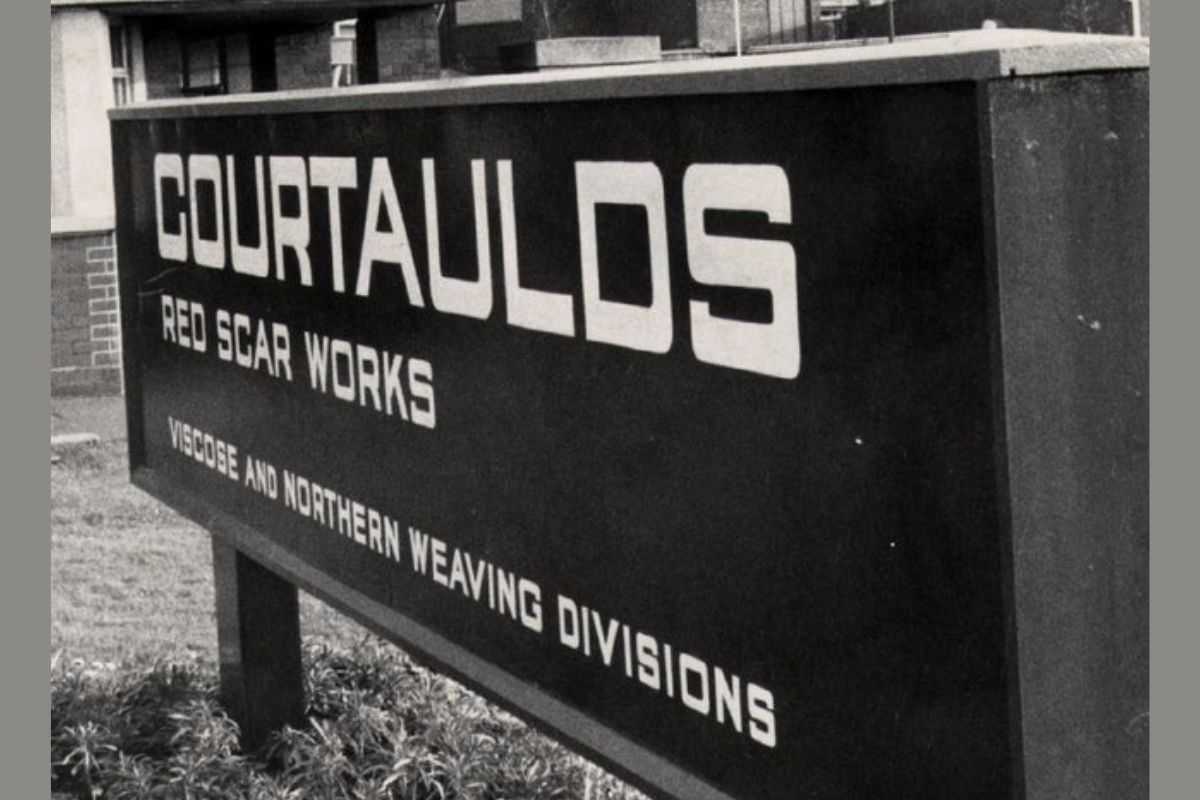

Courtaulds’ Red Scar Mill

For Preston, this period saw a relative peak for industry. This was reflected in the size of the Courtauld’s Red Scar Mill: the largest factory in the area, employing over 3,000 workers, roughly 1,000 of which were migrant workers.

Before the strike, the bosses were looking to ‘speed-up’ productivity – i.e. increase their profits – by increasing workloads at the factory.

Scandalously, behind the workers’ backs, Courtaulds struck a deal with the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) to increase the workers workload: from manning one machine to manning one-and-a-half machines, for the financial reward of ten shillings per week (less than £10 in today’s money).

What this actually meant was a 50 percent increase in workload for a three percent pay rise.

When the union took this deal to the workers, it was laughed out of the meeting, with the workers threatening to go out on strike.

Nevertheless, after a month of limbo, the bosses came down to the factory floor and drew – with red paint – lines half-way down the machines.

To the shock of the managers, the migrant workers – who had been targeted first – spontaneously carried out a sit-in for 17 hours, clogging up the machines.

This showed, at least in their part of the factory, that capitalist production can’t run without the kind permission of the working class.

Strike begins

The three-week-long strike began.

The TGWU immediately refused to support the strike, claiming that the migrant workers hardly attended union branch meetings. Criminally, they stated that they would only support the strikers grievances if they returned back to work.

One of the main strike leaders, Mr A. A. Chaudhry, threatened to withdraw from the TGWU, stating that they would “fight the case on their own shoulders”. At the Continental Cinema, the new found home for striker meetings, the TGWU officers were heckled.

Abandoned by the TGWU leadership, the strikers were diminished in terms of size, funding, and strength. They therefore had to look elsewhere for support.

One of the main focuses of the new ad hoc committee was to build national and even international awareness. This involved reaching out to local councillors, Labour ministers, and even lawyers from New York.

One of the strike advisors, the writer Jan Carew, called on the Commonwealth governments to intervene:

“We are calling for solidarity…This is no longer a parochial affair and is now of international interest.”

All of these overtures, however, proved to be a dead-end.

The workers were conscious that the strike was not growing by the end of its first week. They became desperate for some form of direction and strategy.

The Racial Adjustment Action Society (RAAS) thereby stepped in to lead the strike, giving hope to the strikers that their ‘profile’ would be raised.

Black nationalism

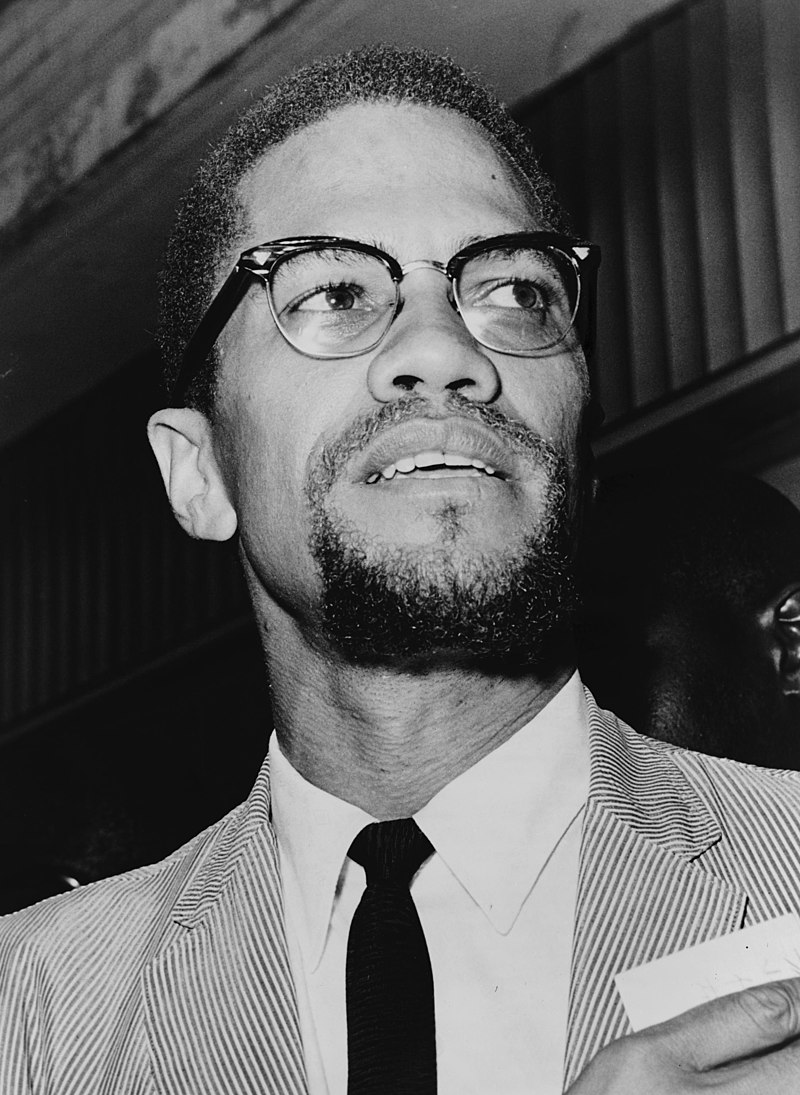

By the 1960s, the anti-racist movement was interlinked with the anti-colonial, civil rights, and Black nationalist struggles across the world. These links were further forged with visits by Malcolm X in 1964 and 1965, which saw the setting up of the first Black nationalist organisation in Britain, the RAAS.

Against a backdrop of increased racist rhetoric in British politics at the time, in addition to the lack of representation in ‘white’ trade unions, the presence of Black nationalism at the time expressed, in part, the turning away from a labour movement that had isolated black and Asian workers.

This outlook was especially promoted by one of the main leaders of the RAAS, the Trinidad born Michael de Freitas – later Michael X.

The RAAS, especially Michael X, genuinely hoped to bring the Red Scar Mill strike international publicity, connecting some of the lessons of antiracist struggles from Bristol and America.

The RAAS leadership itself was confused in regards to a strategy. Roy Swah called for a separate Black union, whilst Michael X argued against this.

Their perspectives on what was the core aim of this struggle was also confused. Rather than seeing this as a struggle between wage-labourers against capitalism, with racism benefiting the bosses by dividing the workers, the strike was rather seen as only a race issue.

Any attempts by the migrant workers to play down the racial aspects in the strike were sounded out by Michael X, who at one of the ad hoc committee meetings declared:

“We have one enemy, the white one who is oppressing us. We are now at war, a war we are losing.”

Michael X would later become the first non-white person to be convicted under the Race Relations Act – an anti-racist act that was originally won by the infamous Bristol Bus Boycott, but hollowed out in content – for advocating the killing of any white man who was seen “laying hands on a black woman”, further stating that “white men have no soul”.

Soon after this, he then went on to set up a ‘Black Power commune’ in North London, which was financed partially by John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

Tragically, the commune was suspiciously burned down. By 1975, Michael X had fled back to Trinidad, and was subsequently hanged for murder in relation to two bodies discovered after his second Black empowerment commune was mysteriously burnt down.

Although the Preston migrant workers needed the fullest support in their strike, race-centred rhetoric and perspectives from the Black nationalists in the RAAS served to further isolate the strike, rather than growing it, despite their declaration of this being an ‘international’ strike.

Without the support of the 2,000 white workers in the factory, the strikers would remain a minority.

It is important to reiterate here that the migrant-worker strikers themselves didn’t see the strike as a race issue – it was the managers and TGWU officials that placed this label on the strike, as they tried to denounce it as ‘unofficial’ and ‘illegitimate’.

Interestingly enough, after a 45-minute discussion with the strikers, the local Conservative MP was “absolutely convinced there isn’t a colour question involved in this affair. It is a straight industrial dispute.”

Clearly the bosses party knew what the strike really meant.

Why the strike failed

The failure of the strike was rooted in the isolation of the 1000 black and Asian workers. The question must be posed: why did the white workers refuse to join in, despite working side by side in almost similar conditions?

The main reason was racism, its poisonous legacy, and the failure of the official labour movement to fight against this.

For the British ruling class, racism has historically represented an ideological tool to justify the horrors and barbarism of colonialism and imperialism. Likewise in the metropole itself, it provides the bosses and the establishment with a powerful tool to divide the working class along racial lines.

The white workers themselves were at best apathetic to the strike, regarding it to be a nuisance.

Without a conscious coordinated campaign from the labour movement, showing how racism weakened the union and the working class itself, the union and white workers succumbed to the poisonous ideas of the ruling class.

The TGWU ended up denouncing the strike as ‘illegitimate’ and ‘unofficial’. Yet, not once throughout the strike was a general meeting called, despite this being actively called for by the striking black and Asian workers.

This in turn alienated the white workers, who did not see the reason for the strike, regarding it simply as a race issue. This further isolated the strike from the rest of the factory.

The role of the trade union leadership – from beginning to end – was blatantly class-collaborationist, racist, and reactionary; in effect, doing the bidding of the British establishment.

Almost immediately after the wildcat strike started, the union began a campaign to get the migrant workers back to work. The TGWU representative for the region declared to the press that the strike was ‘unofficial’ and ‘racial’. “I could have said it was ‘tribal’, but that might have been a bit unfair,” he stated.

The racism oozing from the trade union leadership was a symptom of their narrow, conservative, short-sighted, reformist outlook. Then, as now, they completely accepted capitalism.

If the union officials had sided with the militant migrant workers in their strike, and called on the other 2,000 workers to join them, this would have undoubtedly upset their relationship with the bosses. But it would have greatly strengthened the union by forging bonds between workers of all colours, and by raising consciousness as to the real class enemy.

By the start of the third week, however, despite the growing media attention nationally and internationally, demoralisation set in. At this point, some 110 strikers pledged to join a hunger strike outside Downing Street, but this did not take place.

At this point, the TGWU renegotiated with the bosses and agreed to a 30 percent increase in workload for an increase of 3 pence per hour. The strike was lost.

Legacy and lessons

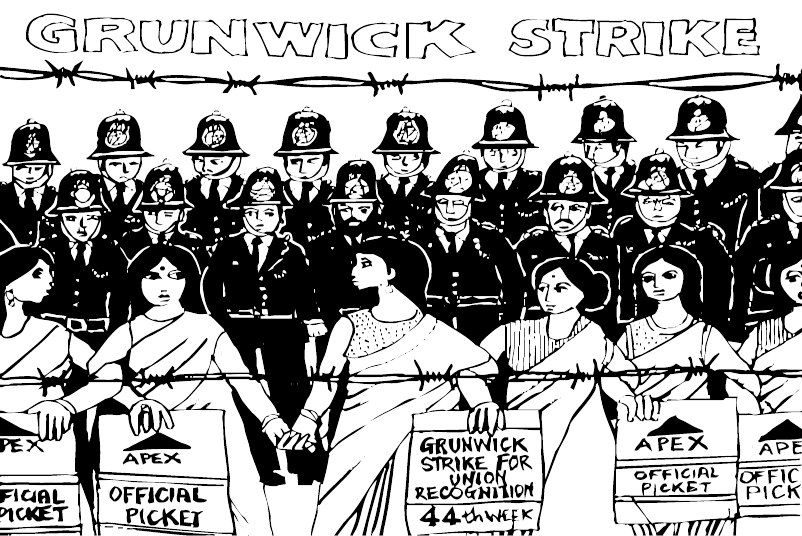

Inspiringly, and without precedent, for the first time, migrant workers fought back against the bosses.

When their union leadership let them down, they organised themselves, showed enormous solidarity against the odds, and gained national and international attention in the process.

Likewise, the Preston migrant-worker strike exposed and fought racism within the labour movement itself.

With growing racist rhetoric in Britain today, alongside a strong desire for a fightback, we should be inspired by the Preston migrant-worker strike.

This struggle exposed how racism is used as a vicious tool to divide workers, and thereby to thwart efforts to organise and fight the bosses with full united strength.

This shows the need to link the fight against racism with the class struggle – bringing together anti-racist campaigns under a militant class-based programme that offers solutions to problems facing the entire working class.

And where best to look for more inspiration than the 1972 Mansfield Hosiery strike in Loughborough, where not only did migrant workers strike back, but actually won! Watch this space.