Last summer saw a series of far-right riots targeting ethnic minorities and refugees across the UK. The question of immigration is once again at the top of the political agenda, pushed by the ruling class as a scapegoat for Britain’s social problems.

Furthermore, the history of the fight against racism in Britain is rarely, if ever, taught.

For all these reasons and more, we are publishing an anti-racism series called ‘Here to fight, here to stay’ in The Communist, following the key battles, turning points, and lessons in the fight against racism in Britain.

In doing so, this series will illustrate what events in the post-WW2 era shaped the British working class to how it looks like today, its traditions, and its heritage. And it will aim to answer the big questions: what is the material basis of racism in Britain; how do we fight racism and the far right; what is the role of the state and the trade unions; and ultimately, how can we end racism once and for all?

In 1963, Bristol became a focal point in the fight against racial discrimination. A mass boycott exposed the Bristol Omnibus Company’s ‘colour bar’, preventing black and Asian workers from working on the buses.

The campaign, inspired by the struggles led by Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr., successfully ended this discriminatory practice. It was a landmark event, sparking the beginning of the British civil rights movement.

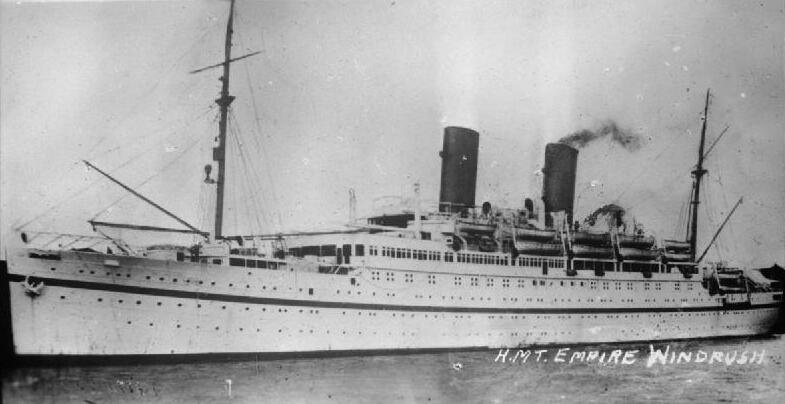

After World War Two, Britain’s economy was in ruins and desperate for labour. This prompted the Labour government to relax immigration controls between 1948-1962.

In 1947, preparations were made for the 1948 British Nationality Act, which granted colonial subjects of the British Empire automatic UK citizenship.

The legislation was partly introduced to stem the struggle against colonialism. But it also aided the hiring of cheap, super-exploitable labour from the Commonwealth countries, including the West Indies, India, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Ghana.

The majority of immigrants who came from the Caribbean islands during this period, in search of a better life in the metropole, had little idea of the hardships they would face. Many had served in the British army and munition factories in WW2, and prospects for work and upward mobility were limited at home.

Black Britons in the 1950s

The British ruling class had long promoted racist ideas to defend the loot, slavery, and super-profits of Empire. But now these ideas took on a new character within the metropole.

Black and Asian workers’ role as cheap labour led them to become synonymous with poverty, bad jobs, and social ills. This enriched the British capitalists, whilst fomenting racist attitudes.

Newcomers to Bristol were therefore shunned by the white population; excluded from all aspects of social and cultural life. They were forced to band together, forming tight-knit social groups, largely confined to the St Pauls area of the city.

Their visible presence made them an easy scapegoat for the district’s pre-existing derelict conditions. To native Bristolians, St Pauls became known as a notorious area riddled with violence.

Black Bristolians experienced gruelling conditions when it came to housing. They were excluded from boarding houses, with signs on display reading: ‘No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs.’ Even if they could find accommodation, difficulties with affordability meant that up to six people would have to share a room.

The streets were unsafe, with the Teddy Boys – a gang of racist hooligans – terrorising immigrants. Their violence had reached an explosive point during the 1958 Race Riots in Notting Hill and Nottingham. A year later, Kelso Cochrane was brutally murdered in a racially motivated attack.

The police, however, took a lax approach to dealing with the Teddy Boys, dismissing reports of racial assaults from the black community. In Cochrane’s case, the detective investigating the murder initially downplayed the racial motive, suggesting robbery was the cause instead.

These two tragic events led the black community to organise and protest against these injustices, with over 1200 turning up for Cochrane’s funeral in solidarity. In turn, Communist Party member Claudia Jones organised the first Caribbean carnival at St Pancras Town Hall, the forerunner to today’s Notting Hill carnival.

Black workers faced limited opportunities to progress their careers, often relegated to poorly paid and unfulfilling jobs. Princess Campbell, one of Bristol’s first black ward sisters, reflected on the discrimination she faced in nursing:

“The English nurses would have the easiest jobs; we, the black nurses, would be in the sluice cleaning bedpans and vomit bowls. You couldn’t complain because the ward sister would make a report. You had to put up or shut up. But there was a problem in that hospital – they didn’t accept black nurses as ward sisters. I was told time and time again, ‘You’re wasting your time staying here because you won’t be a ward sister.’”

When she asked why, she was simply told: “The white nurses won’t work under a black sister.”

At the same time, there were no laws against racial discrimination. Many racist employers took advantage of this to avoid hiring black workers. By 1958, black unemployment in Bristol stood at around five percent, more than double the rate for white workers.

How the boycott began

The Bristol Omnibus Company gained particular attention in 1961, after the Bristol Evening Post published a series of articles accusing the state-owned company of operating a colour bar in the midst of labour shortages on the buses.

General manager Ian Patey refuted this, arguing that the company employed black people in the garages and canteens. In other words, he was happy to employ them in menial positions where they would not be facing the general public.

He later defended the policy to the city council in March 1962 at a Joint Transport Committee, stating that there was “factual evidence that the presence of black crew on the buses would downgrade the job and would drive existing staff away”.

Efforts were made by a group of Jamaicans to make the council aware of their grievances to no avail. The council instead endorsed the views of Patey:

“Views were expressed by several members of the Committee and in making reference to Mr Patey’s statement and appreciating the difficulties in this matter, it was advocated that there should not be any change in the existing employment policy.”

The racist policies of the bus company were also actively promoted by a significant section of white unionised workers.

In 1955, a local Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU) branch that represented bus crew actively went on strike to oppose the employment of non-white bus crew in the West Midlands. The union had even imposed a cap on non-white bus workers. This was despite the official position of the union opposing colour discrimination.

Then, as now, racist poison was being poured into society by the ruling class and its representatives, in order to divide the working class.

No lead was taken from the right-wing union leaders to fight the scourge of racism. They had a completely class collaborationist outlook. Their passivity and inaction, whether consciously or unconsciously, led them to defend racist ideas spewed out by the bosses and the ruling class as a whole.

TGWU, the forerunner to Unite, was no exception. Led by right-wing leader Arthur Deakin up to 1955, he explicitly denied racism as an issue, and stated the strikes were over fears of economic issues.

Therefore even in the union ranks, there were those who aped racist ideas, justifying their behaviour by repeating racist caricatures that black men “were dangerous to white women”.

In Bristol, the bus company’s management claimed they had no objection to employing black people, but “were not prepared to face a showdown [with the unions] which would have led to strike action”.

Both the Conservative-run city council and the TGWU leadership showed that they were unwilling to act to fight against racism. On the contrary, they actively supported it.

Isolated, with no other avenues to fight back, Roy Hackett, Owen Henry, Audley Evans, and Prince Brown established the West Indian Development Council (WIDC) as an action group to organise West Indian Bristolians against the colour bar.

The group gained momentum after meeting a talented, young communicator called Paul Stephenson, Bristol’s first black social worker, who was elected WIDC spokesperson.

Stephenson recognised that the bus issue would expose racism, and serve as a lightning rod for the anger felt within the black community.

The WIDC organised for Guy Reid-Bailey, a young Jamaican immigrant to Britain, to apply to the Bristol Omnibus Company as a conductor, in order to establish that there was a colour bar.

All the preparations had been made to ensure that a vacancy existed for which Reid-Bailey was qualified. When he arrived for his interview, he was told by the manager that “the vacancies are full” and that “there’s no point having an interview, we don’t employ black people”.

On 29 April 1963, a press conference launched the bus boycott, consciously adopting the successful tactics of the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott.

It was unclear at first how the boycott would be received among other West Indians. They depended on the buses to get to work.

Roy Hackett understood their concerns: “They think because they are few in numbers, if their bosses see them on TV or in the paper…they think they would have had the sack.”

This was their first experience of political struggle in Britain. And while many sympathised with the boycott, many remained passive.

Leadership played a key role. The WIDC rallied 3000 black Bristolians, of whom a significant section were prepared to make the necessary sacrifice to fight for their interests.

Hackett boldly asserted: “If somebody’s not prepared to do something so that the rest can benefit, then life would never be worth living at all.”

Subsequently, on 6 May 1963, a 200-strong protest of black people was organised in Bristol against racial discrimination, one of the first black-led marches in Britain.

Colour bar falls

The boycott’s strategy aimed to raise awareness of the issue, applying mass pressure on the bus company to end the practice. It didn’t take long for the boycott to gain wider support across the city.

The campaign even made waves across the country – and internationally, in the West Indies. High Commissioner for Trinidad and Tobago, Sir Learie Constantine, used his diplomatic position to apply pressure on the Bristol Omnibus Company.

Stephenson engaged the press, who eagerly showcased bus workers openly expressing racist views. This undermined the TGWU’s official stance on the matter, as they were not doing enough to get the “race virus out of the systems of their rank and file”.

Hackett organised groups of people to stage road blockades and sit-down protests: preventing the buses from going through the city centre, and enabling activists to fraternise with passengers, encouraging them to join in the boycott.

The TGWU had grown hostile towards the WIDC, blaming their disruptive tactics for creating the conflict. But this did not distract Stephenson, who kept the pressure on the Bristol Omnibus Company throughout, seeking to drive a wedge between management and the bus workers.

“The ordinary workers took their cue from the Bristol Omnibus Company,” Stephenson correctly stated.

At a May Day rally, the Bristol Trades Council organised a demonstration outside the TGWU office, highlighting the hypocrisy of the union’s officials, who condemned racism in South Africa while overlooking it at home. Bus workers were heckled by students and other trade unionists. This was an important turning point.

The TGWU became increasingly isolated within the labour movement, as other leading figures like Bristol MP Tony Benn and Labour Party leader Harold Wilson publicly supported the boycott. This pressure pushed them to go into negotiations with the bus company.

The media drew parallels to the US Civil Rights Movement. This alarmed the ruling class and prompted calls for action. The editor of the Bristol Evening Post cautioned: “This is time for Cool Heads. We want no Little Rock in Bristol” – a reference to the civil unrest following the desegregation of schools in the American South.

The Telegraph noted how the struggle against racism was gaining an international character. “The dark races are conscious of a common interest and will support one another’s struggles for emancipation,” the reactionary paper asserted.

By coincidence, on 28 August 1963, the day of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, both the TGWU and Bristol Omnibus Company came to an agreement to overturn the colour bar.

Pressure from all sides, the loss of revenue on the buses, the isolation of the TGWU within the labour movement, and the fear of the boycott escalating into a wider uprising had forced the hands of both the union and bus company.

Legacy and lessons

The bosses explicitly used racism to divide and rule, enriching themselves by appealing to white bus workers and emphasising their ‘special role’.

Cyril Buckley of the Bristol Omnibus Company claimed: “Once you change this job over, and it becomes known as a coloured man’s job, well then the white man does not take any further interest in it.”

Bus wages in Bristol had sharply declined since pre-war levels, when they matched those of skilled workers. After the war, bus crews had to work up to 100 hours a week just to earn the average weekly wage of £20.

Just as complicit was TGWU regional secretary, Ron Nethercott, who later excused himself of any blame, claiming that economic pressures, not racism, were the reason bus workers supported understaffed rotas.

In fact, Nethercott had co-opted a black TGWU union member – Bill Smith – to sign a public statement to undermine the boycott for causing harm to racial unity!

TGWU union bureaucrats were utterly detached: concerned with securing their own positions and careers; defending management’s racist policies, rather than actively confronting these issues head-on.

The opportunity existed to strengthen the TGWU, by uniting workers of all colours, some of whom were already TGWU members, and exposing how racism was being used to distract white workers from their declining conditions.

In order to wage an effective fightback, racism had to be rooted out of the union, with unity between black and white workers forged through a struggle against their common enemy, the bosses, who were the real reason for workers’ poor wages and conditions.

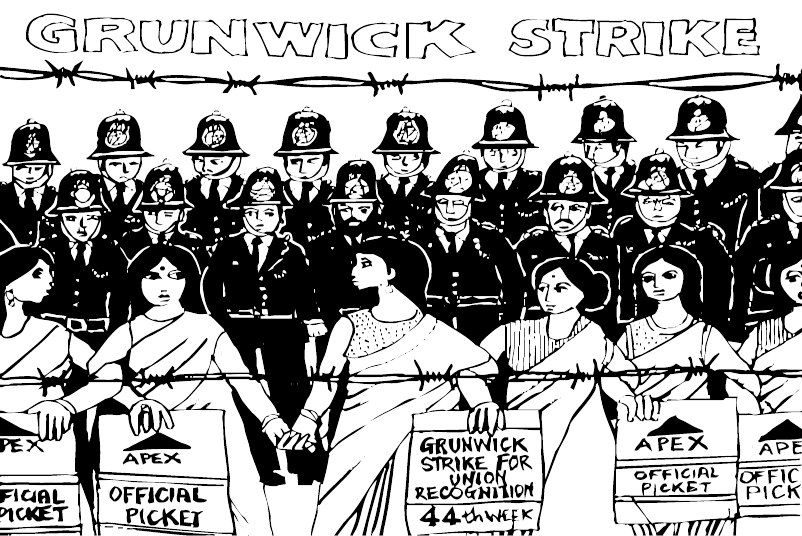

Instead, it would take many struggles from black and Asian workers over two decades to force themselves into the British labour movement.

The bus boycott was the first major victory in the struggle against racial discrimination in postwar Britain. The pressure on Harold Wilson to support the boycott led his government to implement the 1965 and 1968 Race Relations Act, banning discrimination in public places and in employment.

Legislation was a partial victory. But it did not end racism – rooted in centuries of colonial brutality, and proven to be a powerful weapon in the hands of the ruling class to divide the working class.

Nevertheless, this was a turning point. Migrants to Britain, who had put up with discrimination and bigotry since their arrival, were now beginning to fight back.

The Bristol bus boycott was one of the first times black people actively took on the fight against racism in Britain – expressing their discontent en masse, and consciously taking on the fight against discrimination – and won.

This landmark victory was the beginning of a long and ongoing struggle against racism, which shaped the proud traditions of black Britons and the wider working class in Britain.

The importance of militant mass action in combating racism and discrimination, alongside the treacherous and class-collaborationist role of the trade union leaders, remain as lessons of utmost importance to this day.

We will continue to explore how the struggle against racism in Britain developed in our series. Next up: immigrants strike back in Preston.