As part of the recent Annual Budget, George Osborne, the Tory Chancellor, announced government plans for a new “Help to Buy” scheme, aimed at increasing the number of residential property purchases. Far from solving Britain’s housing crisis, Osborne and the Coalition have helped to create the conditions for yet another bubble that will undoubtedly burst. Adam Booth looks at the housing question in the UK and latest government policy.

As part of the recent Annual Budget, George Osborne, the Tory Chancellor, announced government plans for a new “Help to Buy” scheme, aimed at increasing the number of residential property purchases. Far from solving Britain’s housing crisis, Osborne and the Coalition have helped to create the conditions for yet another bubble that will undoubtedly burst.

For the last thirty years, the ruling class attempted to delay the outbreak of a crisis of overproduction by artificially maintaining demand and expanding the market through the use of credit. With the one hand the capitalists took from the workers, and thus reduced demand, by cutting wages in order to increase profits; whilst with the other hand, the capitalists lent to the very same workers, encouraging ordinary people to borrow and spend like there was no tomorrow. But eventually the day of reckoning came: ordinaries families couldn’t pay back their debts; the bubble burst; and the crisis erupted.

Hegel, the great German dialectician, once wryly commented that the only thing one learns from studying history is that nobody has ever bothered to learn from history. Now, with this latest policy announcement from Osborne we have another perfect example of Hegel’s aphorism: despite the dire effects of the recent housing bubbles, sub-prime mortgage scandals, and credit crunches in the US, Spain, Ireland, and elsewhere, Osborne and company have decided that the best way to get Britain out of recession is to…re-inflate the bubble!

As the Financial Times comments:

“It is as though the chancellor has learnt no lessons from the financial crisis itself. After all, the whole blow-up stemmed from years of excessive US subprime lending to people who could not afford it, and was aided and abetted by the very existence of a government-sponsored structure in Fannie and Freddie that gave the banks excessive scope to expand business.

“The programme that arguably sowed the seeds for those abuses – Bill Clinton’s 1995 National Homeownership Strategy – now looks like an eerie precursor of Mr Osborne’s new plan. Help to Buy is the precise opposite of what sensible economists believe the UK needs to do.”

“Help to Buy” – but does buying help?

The main focus of the new Help to Buy scheme is to encourage banks to lend again to potential homeowners, with the government promising to protect banks against any losses on high loan-to-value mortgages.

This is yet another desperate attempt by the Coalition to artificially stimulate demand in the economy without actually having any government spending and accumulation of additional public debts. The Financial Times described the policy as an “off-balance sheet trick”, a “straightforward accounting wheeze”, and a “little political trickery”.

Such an attempt follows on from other desperate measures such as quantitative easing – and the talk of a “helicopter drop” of money – which equally demonstrate both the failure of austerity and the impossibility of Keynesianism; in other words, which demonstrate the impossibility of a solution to the crisis within the confines of capitalism.

Like all the other desperate attempts to solve the crisis, the Tory-led government have merely sown the seeds for a bigger crisis in the future – in this case by making already overly-inflated house prices even higher and by creating a tremendous risk of default that a future government will have to deal with. According to Robert Peston, the BBC business editor:

“If house-buyers were to take up all the guarantees on offer from the Treasury, some £130bn of new mortgages would be created – all of them with the home owners providing only a sliver of equity, and taxpayers on the hook for a little less than three quarters of losses, in the event that the price of the relevant houses were to fall 20%.

“The Treasury estimates the potential or contingent liability for taxpayers at some £12bn.

“Now to put all this into some context, that £130bn represents well over 10% of the stock of existing residential mortgages at the moment. And it is equivalent to a whole year’s supply of gross mortgage lending by our big banks and building societies.”

As The Economist, and many other commentators, have pointed out, the Help to Buy scheme does nothing to even solve the fundamental problem at the heart of the UK housing crisis: the complete lack of housing, particularly at any affordable level:

“Help to Buy protects banks against losses on high loan-to-value mortgages. This is politically savvy: it should boost lending without emptying the Treasury’s coffers (the government only pays out if the loans go bad). But the economics are dubious. It may have no impact on supply, and merely inflate house prices. It is not at all clear that making it easier for people to take out big mortgages is economically or socially beneficial. And by exposing the government to the housing market it could lead to losses, or American-style long-term backing of mortgages. Unwinding Help to Buy could be painful.”

The new housing policy may help people to buy, but buying property does not necessarily help resolve the fundamental lack of affordable housing; indeed, the increased demand that the Help to Buy scheme artificially creates will – in the absence of any increased supply – simply lead to an increase in house prices, which are already too high for ordinary families.

Robert Peston continues:

“It is an intriguing policy for a number of reasons, not least because some would say it is counter-intuitive to tackle the problem of housing that’s too expensive for young people by stimulating prices.

“Also, there is a reasonable argument that in the boom years, the economy was too dependent on consumer spending, which in turn was generated in part by an over-heated housing market.

“So although we may all be fed up with the economy’s torpor, and would be keen for a bit of renewed growth, it is not clear that any growth sparked by a new housing-linked consumer boom would be altogether healthy.”

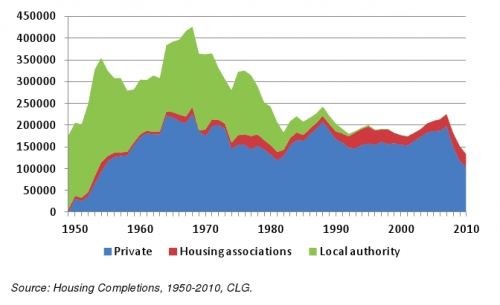

Housing completions, 1950-2010According to statistics, building rates of new housing are at an historic low. In 2007 the New Labour government set a target of increasing the supply of housing by 240,000 additional dwellings per year by 2016, including a commitment to deliver at least 70,000 affordable homes per year by 2010-11. Even this level of construction pales in comparison to historic levels: during the post-war boom of the 1950s, 60s – and even into the 70s – the UK housing stock would regularly see an additional 300,000 dwellings per annum, with highs of over 400,000 in the late 1960s. Local authorities were responsible for regularly adding over 150,000 new homes per year throughout this period; this source of new dwellings was lost by the early 1990s, however, thanks to Thatcher’s policies of Right to Buy, taking away spending powers from local authorities, and promoting the role of arms-length housing associations.

Housing completions, 1950-2010According to statistics, building rates of new housing are at an historic low. In 2007 the New Labour government set a target of increasing the supply of housing by 240,000 additional dwellings per year by 2016, including a commitment to deliver at least 70,000 affordable homes per year by 2010-11. Even this level of construction pales in comparison to historic levels: during the post-war boom of the 1950s, 60s – and even into the 70s – the UK housing stock would regularly see an additional 300,000 dwellings per annum, with highs of over 400,000 in the late 1960s. Local authorities were responsible for regularly adding over 150,000 new homes per year throughout this period; this source of new dwellings was lost by the early 1990s, however, thanks to Thatcher’s policies of Right to Buy, taking away spending powers from local authorities, and promoting the role of arms-length housing associations.

Following the beginning of the crisis in 2007-08, mortgage lending collapsed as the scale of the global housing and credit bubble became evident, leading to a parallel collapse in construction of new-builds. The UK construction sector now struggles to maintain rates of 100,000 new homes per year, whilst the number of households is predicted to grow by around 230,000 per year for the next 20 years.

Housing and speculation

The need for new housing, therefore, far outstrips the ability of capitalism to provide, and the problem is even more acute in areas of the UK such as London and the South East, where, in truth, the housing bubble never really burst. This regional disparity also highlights the uneven nature of how the crisis has impacted upon the UK: cuts to the public sector – following on from cuts to industry and mining in the 1980s – have destroyed whole communities, towns, and regions in the north of England and in Scotland, whilst certain (wealthy) areas within London and the South East – thanks to the government’s determination to rescue the bankers – have continued to see investment.

Indeed, whilst house prices have been slashed in many parts of the country, prices in London have continued to increase, with a price-to-earnings ratio in London that is double that seen in the north of England. In other words, housing is twice as unaffordable for those in London as those elsewhere in the UK!

In this respect, the Financial Times described the Help to Buy scheme as “an accident waiting to happen”:

“The UK housing market – far from having collapsed amid the financial crisis – is still a bubble waiting to pop. While US house prices have fallen 35 per cent from their pre-2007 peak, the equivalent decline in the UK is barely half that. In some hotspots, prices have continued to rise.

“Affordability indices, relating house prices to earnings and loans to income levels, show virtually unchanged UK multiples since 2007 – a stark contrast, again, with the state of today’s US market, where the indices show housing has never been more affordable.”

A large part of the continually high price of London residential property is the speculative way in which this property is treated, with extremely wealthy individuals from abroad who are looking for a profitable investment opportunity flooding the London housing market with their money. According to the Financial Times, such individuals are, in particular, targeting the most valuable properties in the capital:

“Foreign purchasers ploughed £5.2bn on central London houses last year, £1.5bn more than in 2010, according to the think-tank IPPR.

“Jonathan Hewlett, head of London residential at Savills, said the capital’s position as a perceived haven from the turmoil in the eurozone and political unrest in the Middle East was outweighing the possible negatives of a tougher tax regime…

“…The appetite from overseas buyers has pushed up prices rapidly in London’s expensive housing market, which has decoupled from the wider UK housing market. Prices in the capital’s prime market – the top 5 per cent by value – have gained 11.3 per cent during the past 12 months, compared with 0.2 per cent for the rest of the country.”

According to a report by Savills, the estate agent company:

“Overseas investment into London real estate is running at £3.7 billion a year and at this rate, foreign buyers will own all residential property in Greater London by the middle of the next century.

“They are responsible for 34% of all London property transactions although most investment is channelled into high-value residential properties areas such as Mayfair, Kensington, Notting Hill and Chelsea.”

Although such expensive properties are out of range for any ordinary family, the influx of speculative investment in central London has pushed UK owners into inner-city suburbs, who in turn push other homeowners further out and contribute to rising rental prices across the board. As the Savills report continues:

“Inflows at the top end of the market are starting to spread into less central London locations, pushing UK property owners further out. Because the number of foreign investors buying in London has climbed since 1960 and UK owners tend to hold properties for less time than overseas investors, London’s property market is becoming increasingly international, with substantial ramifications.

“External property investment has been driven recently by upheaval across the Middle East; central London property has become a financial parking space for high net worth individuals in a period of low interest rates and high political and economic volatility. Increased purchases from Greece, Spain and Italy suggest a similar motivation.”

To add insult to injury – and to further prove the speculative nature of this investment in London residential property – many of these newly bought mansions lie empty, sitting idly in the hope of being sold for a tidy profit in the future.

Once again we see the crisis of overproduction manifested in the most absurd contradictions: on the one hand we see an enormous need for housing in society; on the other hand, we see enormous properties that are completely empty. Whilst consistently being told by the bourgeois politicians and media that large families of immigrants or “lazy benefit scroungers” are to blame for the lack of housing – and hence the “need” for policies such as the curb on immigration or the “bedroom tax” – we simultaneously see that there is tremendous amount of wealth in society that could potentially be used to build new houses, but which is instead used to speculatively buy up mansions that are left to gather dust.

Supply and demand

So, if there is such a great need for housing, why aren’t more homes being built? Surely if house prices are high, then this should act as a signal to investors to divert money into the construction of new homes? Shouldn’t supply increase to meet demand, and thus reduce prices? After all, this is how capitalism and the invisible hand of the free market work!

The simple answer presented by the bourgeois media is that there is a “supply-side” issue – i.e. the supply of new homes is restricted, primarily due to planning laws and restrictions, and thus the forces of the market cannot work to reduce prices. The picture painted by these sources is one of NIMBYism and individual interest, with homeowners in local areas putting pressure on councillors and politicians to restrict development, thus limiting supply, increasing house prices, and helping these same homeowners “gain wealth”.

To the extent that supply-side issues of planning permission and regulation may be to blame, this only demonstrates the decrepit nature of capitalism – an inherently anarchic system, in which the provision of needs is left to a handful of privately owned monopolies (and construction is no exception in this respect) that are producing blindly and independently of one another for an unknown market, competing for market share and greater profits – and the incompatibility of combining this senile and irrational system with any sort of plan.

Furthermore, the bourgeois commentators simple explanations contain two obvious errors. Firstly, a uniform increase of house prices does nothing to generate any real wealth. If the price of a homeowner’s property increases, how are they supposed to realise this supposed increase in wealth? This can only be achieved in one of two ways: either the increased price of the house can be used as a means by which to borrow more from the banks for consumption – a strategy that was used by capitalism to artificially increase consumer spending over the past few decades and which ended with the disaster of the current crisis; or the homeowner can try to sell the property and pocket the difference between the price the house was bought for and the price it is sold at – but then one would have to buy another house or begin to rent instead, and both of these options would be more expensive due to the general increase in house prices and the influence this has on rents.

In other words, a uniform increase in house prices due to a lack of supply does nothing to create any new wealth – i.e. new value. As Marx explained in his many writings on economics, new value is only created by the application of labour in the process of production. In the case of housing, this means the construction of new housing or the development and improvement of existing homes.

The impression of increased wealth due to an increase in house prices is illusory and fictitious, and any attempts to stimulate consumer spending through increased property prices are simply another form of credit bubble – artificially expanding the market today at the expense of tomorrow.

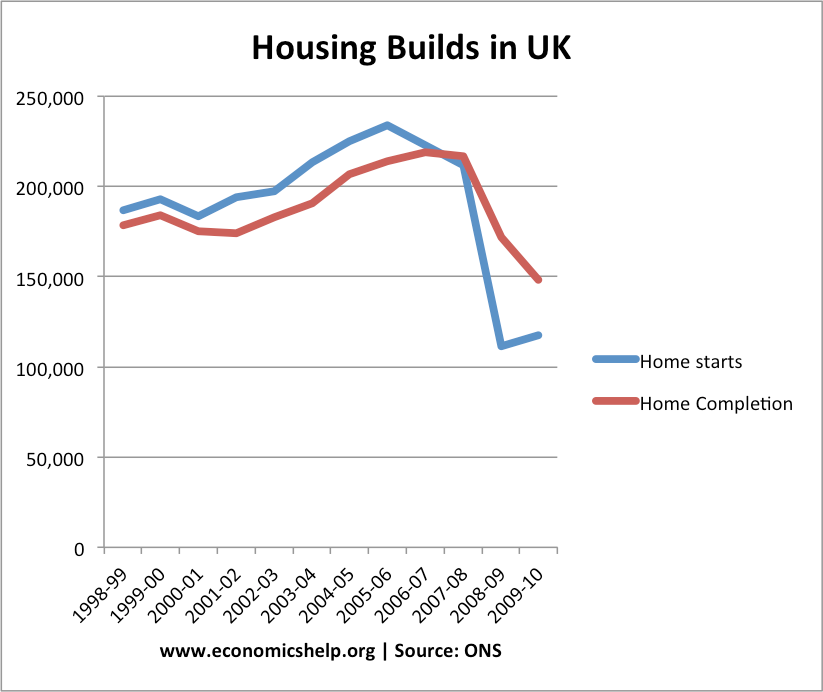

Secondly, in relation to the simple explanation that the lack of any new housing supply is due to planning restrictions, it should be pointed out that construction companies were happily building away before the 2007-08 crisis when the credit taps were still flowing – i.e. when mortgages were freely available to maintain demand. Following the outbreak of the crisis, construction of new builds fell as bank lending for mortgages – and for construction companies – froze up and demand slumped. These are shown in the figures for construction: between 2003-07, construction was going steady at over 200,000 new homes per year; after 2007-08, construction halved to just over 100,000 per year.

Secondly, in relation to the simple explanation that the lack of any new housing supply is due to planning restrictions, it should be pointed out that construction companies were happily building away before the 2007-08 crisis when the credit taps were still flowing – i.e. when mortgages were freely available to maintain demand. Following the outbreak of the crisis, construction of new builds fell as bank lending for mortgages – and for construction companies – froze up and demand slumped. These are shown in the figures for construction: between 2003-07, construction was going steady at over 200,000 new homes per year; after 2007-08, construction halved to just over 100,000 per year.

If it was simply a supply-side issue of planning restrictions and a lack of land, then one would expect construction of homes to have been consistently low for some time. It is true that the pre-crisis construction of new houses was low by historic standards (due to the policies introduced by Thatcher in the 1980s), but this does not explain the current lack of supply.

This highlights that the problem is not simply due to supply-side restrictions, but also due to demand. In this sense, it is important to clarify what is meant by “demand”. The demand within the market under capitalism does not represent the actual needs and wants in society, but rather the ability to purchase what is produced. Demand in this sense is therefore often referred to more precisely as “effective demand”. This divergence between demand in terms of needs and demand in terms of the ability to buy is a reflection of the contradiction between the use-value and the exchange-value, as discussed by Marx in Capital and elsewhere. In turn, this contradiction is ultimately a reflection of the capitalist system itself, whereby the means of production are privately owned and production itself is only for profit and not for societal needs.

To put it simply: of course there is a need for new housing in society; the problem is that ordinary people do not have the ability to buy it! Whilst there may be a need for over 200,000 new homes per year, unfortunately there are not 200,000 families per year who can afford to become homeowners.

Marx himself never denied the role of supply and demand – i.e. of “market forces” under capitalism. However, Marx explained – for example in “Wages, Prices, and Profits” – that the market forces of supply and demand would express themselves through price signals in order to divert investment in the economy. High supply and low demand would result in depressed prices, meaning that capitalists would be producing at a loss in order to sell; thus future investment would be put elsewhere, production would be wound down, and supply would decrease to match demand. Low supply and high demand would produce inflated prices, resulting in super-profits for the capitalists in that sector; thus other capitalists would divert their money to this sector in order to gain a slice of the pie, new production would come online, and supply would increase to meet demand.

All of this assumes the free movement of capital from one sector to another, i.e. a free market with no restrictions on any increases in supply, as may be the case with housing. However, the bourgeois economists who talk about the wonders of supply and demand, the free market, and the invisible hand do not see that even the freest market will suffer from the contradiction of overproduction.

Marx also made an important contribution in explaining that ultimately the market forces of supply and demand could explain prices, but could not explain the actual value of commodities. In other words, what determines the price of a commodity when supply is equal to demand and these market forces cancel out and are in equilibrium? For example, why is a house more valuable than a car, or a car more valuable than a pen?

In this equilibrium case where supply and demand are equal, the value of a commodity must be determined in some other way, which Marx identified as being due to the socially necessary labour time crystallised within the commodity. Wealth, in other words, cannot simply be conjured out of thin air, like a magician pulling a rabbit out of a hat, but can only be created through the application of socially necessary labour in the production process. Hence why a uniform increase in house prices does nothing to create any real new wealth, as explained above.

Contradictions reflected

The prevalence of empty residential properties – owned simply as investment vehicles for international billionaires who are awash with cash, but with very few profitable opportunities available to them – has led to even more perverse contradictions: such buildings, as well as commercial properties that have become empty due to the recession, are now filled by “resident guardians”, who pay discounted rents to specialist “protection firms” in order to live in empty properties on a temporary basis. As The Economist reports:

“One booming industry is providing ‘resident guardians’ to landlords—workers who pay a token rent to live in empty buildings and keep watch on them. Many businesses are worried about leaving their properties empty, says Steven Davies, an executive at Camelot, the biggest protection firm, as their fear of squatters has intensified.”

Here we have the most absurd of situations, which is only possible due to the completely anarchic and irrational nature of capitalism itself: billionaires park their money in high-value properties as speculative investment; these purchases drive up house prices, and thus rents also, across the region; said properties are then left empty; and the wealthy owners then pay “protection firms” and “resident guardians” even more in order to ensure that these properties are kept empty over the long term.

Latest figures from the English Housing Survey – an in-depth government study of housing – estimate that almost 5% of the English housing stock is actually vacant, equating to a total of over one million homes. Some of these properties will be empty mansions bought up as an investment by billionaires; others will be derelict social housing that local authorities and housing associations do not have the money to renovate; and some of these vacant homes will be repossessed properties, now officially owned by the banks due to mortgage defaults during the crisis. In addition, these one million vacant houses do not even include second (or even third) homes, such as holiday homes for the rich.

Such figures only further demonstrate that the housing crisis is not simply a supply-side issue, as the bourgeois media – who wish to paint the problem as the fault of “government meddling” and “state intervention” – try to say. Rather, the lack of affordable housing and the absurdity of empty homes show the degenerate nature of capitalism, which is no longer able to develop the productive forces and provide even the most basic of necessities for the vast majority of people. For example, if the global rich are so awash with money, why can’t they invest this in the construction of new homes?

The problem lies in the nature of capitalism and the fact that it is a system where production is for profit; where investment by capitalists is only done in the name of making profit, not for societal need. The reason that these wealthy individuals don’t invest their money into constructing new buildings and thus ease the housing crisis– instead choosing to invest speculatively in existing mansions – is the same reason that the capitalists in all industries do not invest, but instead choose to sit on mountains of cash: capitalism is in the middle of a deep, organic crisis resulting from the contradiction of overproduction, in which the expansion of the productive forces comes into conflict with the limits of the market – i.e. with the ability for people to buy commodities and thus enable the capitalists to realise their profits through the act of selling.

In other words, workers cannot afford to buy back the very goods that they produce, and this includes housing. As mentioned above, the capitalists were able to temporarily get over this contradiction in the past through the use of credit. In the case of housing this reflected itself in the use of “sub-prime” mortgages – lending people the money to buy homes, but were never likely to be able to pay back. Again, the effect of this was to artificially expand the market in the short term, but only at the expense of sowing the seeds for an even greater crisis in the future – a crisis we are living through now.

The housing crisis – including the contradiction of empty mansions alongside homelessness – is ultimately a reflection of the contradictions of capitalism itself: the contradictions of an anarchic and irrational system, where production is for profit and not for social need.

Certain figures in the labour movement have put forward a Keynesian solution to the housing crisis, which essentially boils down to the government instigating and funding a mass programme of residential construction. Such a programme, it is said, would also act to stimulate the economy, reducing unemployment and increasing demand. If the idea is to sell any publically constructed homes, then the question must again be asked: who will be able to buy these new houses? If the proposal is for such homes to be publically funded and owned, then the question becomes: where does the government get the money from for such a large scale programme of housing, given that the financial markets and credit rating agencies are telling the government to do the precise opposite and cut back on public spending?

The truth is that this crisis of housing will not be solved by Osborne’s latest scheme, nor can it be solved at all within the confines of capitalism. It is the task of the labour movement leaders to fight for a socialist solution to the housing crisis: to take empty homes into public ownership and to nationalise the banks and the major construction companies in order to fund and undertake a mass public programme of council housing. Only the abolition of this rotten capitalist system and the socialist transformation of society can provide a roof over the head for all.

[For further analysis on the state of UK housing, see “The Housing Question” parts one, two, and three.]