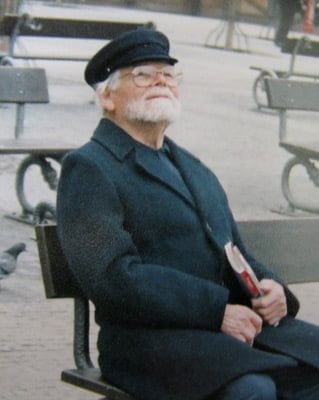

Comrade George McCartney passed away in November 2007 at the age of 90.

Comrade George McCartney passed away in November 2007 at the age of 90.

George was active in the trade union movement and Labour movement for

most of his life and it is fitting that we remember him a year after

his death. We are reproducing the tribute given at his funeral service

by his sons Sean and Neil in Cambridge last December.

Sean McCartney: We are here to mark the passing of George McCartney – it seems very odd to call him George – and if what I have to say is mostly political, that’s because he was always an intensely political person. He born in Liverpool, very appropriately, in the year of the Russian Revolution, and from his early 20s was loyal to the ideas that inspired it.

When he left school he was apprenticed as an electrician and became an engineer in the new and growing telephone industry. As soon as he started work he became involved in the trade union movement. He believed firmly in the ability of ordinary people to group together, fight for their interests, and change society – they only lack the necessary confidence in themselves. He used to say that the key to the power of the officialdom in the union movement lay in their ability to persuade the members to ‘leave it to us’ – the leaders, the experts – and not to take action on their own behalf. Because once people do take action, and achieve things, and realise their power, well, where would it end? One of his favourite sayings, was ‘appetite comes with eating’. That’s how revolutions start.

He was in the Post Office Engineering Union for a period, and then joined the Electrical Trades Union in 1940, remaining a member for the rest of his life, through its various transformations. In 2001 he was presented with a medal to mark 60 years of membership, and altogether he had a remarkable 67 years membership of the ETU. And he was a very active member of the trade union movement – as a shop steward, branch officer, delegate to conferences and so on. And for many years he was Treasurer of Liverpool Trades Council.

But even more important for George was politics. His first involvement was as a member of the Independent Labour Party. But a crucial turning point for him came just before the War, when Ericssons, the firm he was working for, sent him to Leeds. There he came into contact with Marxism for the first time, in the form of the Workers’ International League, always known as the WIL, then a tiny group of a few dozen people.

Attitude to War

What seems to have crystallised his change of view was the attitude to the War – it hadn’t started but everyone could see it coming (George used to mention an episode in an American film of the time, set in a newspaper office, where someone goes to the editor and says, we don’t have a headline story for the front page tomorrow. The editor thinks for a moment and says – put "War Looms in Europe."). The ILP’s position was a pacifist one – they were opposed to war. War was evil. So when the government introduced conscription and began to register men of military age, its members registered as conscientious objectors. George was rather unhappy about this, but went along with it. The WIL had a completely different view. The labour and trade union leaders supported the war, most workers accepted this and were prepared to go into the army. The WIL’s position was very different from the nationalist position of the LP and TU leaders. But its view was that making a personal protest – war is terrible, I won’t join in – was pointless. In order to influence people you have to be where they are. As the WIL put it, "follow your class."

So he joined the WIL and for the rest of his life supported its ideas, which were chiefly articulated by its leading theoretician Ted Grant, for whom he always had a tremendous admiration. Ted, who died last year, was born only three or four years before George, but George said he seemed so much older, because he knew so much. Ted’s ideas were of course the ideas of the ‘old man’ as he was referred to in the WIL, Leon Trotsky, then living in exile in Mexico, but soon to be assassinated by Stalin’s secret police.

Deane Family

In Liverpool the unofficial HQ of the WIL was the Deane family home at 99 Hurlingham Road. He knew all the family, and frequently visited ’99’ as it was always known, not just for political purposes. In one of his letters to Jimmy Deane, after he had been called up, he refers to the ‘Bacchanalian orgies’ at 99, which seemed to have involved Gertie Deane, Jimmy’s mother, playing Abdul Abulbul Emir on the record player, and people doing their party pieces. George used to sing Miss Otis Regrets, and he and Gertie became well known for their rendition of the Beaux Gendarmes.

George spent most of the War in the Army, in North Africa and Italy. After demobilisation he came home and resumed political activity in the Revolutionary Communist Party, the RCP, as the Trotskyists were now called.

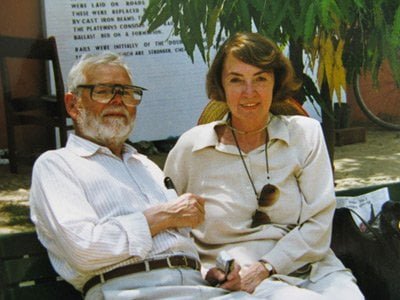

|

| George and Irene |

Despite the hard work of these comrades, the situation was too unfavourable, and in 1949 the RCP decided to wind itself up and told its members to join the Labour Party. George told the story of how on the day the RCP officially dissolved, a group of members went to see Laura Kirton, then and for many years the Secretary of the Labour Party in Walton. She answered the door. They explained why they had come, The RCP dissolved today, they wanted to join the Party, ‘Ah Yes’, she said, leaning against the door, ‘I understand, but what’s the hurry?’. Nevertheless Laura became a firm political ally and friend.

Not long after this, two members of the Labour League of Youth – Irene Proll and Beryl Smith – were invited to ’99’ by Brian and Jimmy Deane. Brian said that they had ‘some good records’ but the real purpose of the invitation was political. George was there and as Irene puts it now, ‘we just hit it off right away’. After that there was never anyone else for either of them.

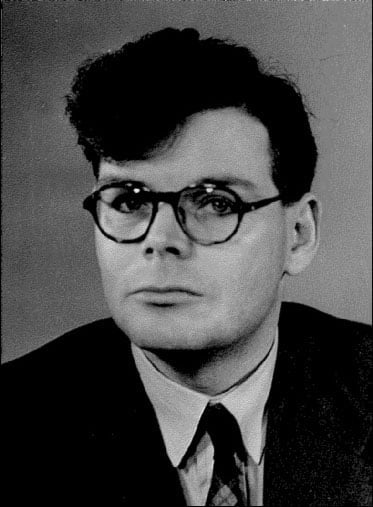

George and his comrades soon won leading positions in the Liverpool Labour Party, and 10 years later he was selected to be the Labour candidate for Walton in the General Election of 1959. The portrait taken for his election address is in front of you.

For Neil and I, aged three and five, that election campaign was very memorable, chiefly because – and it was rather ironic, given George’s occupation – when the campaign started, someone came to our flat and – marvel of marvels – installed a telephone. We thought this was wonderful – the election meant nothing, but a phone! But our excitement was as nothing compared to our disappointment when, after the election, they came back and took the phone away again.

I can also remember being taken to a Labour Party rally in St George’s Hall in Liverpool, given a teddy bear and told to go on the stage and present it to a strange man I had never met. Years later I was told that the strange man was the Leader of the Labour Party, Hugh Gaitskell – and that it was all Laura’s idea.

Neil McCartney: George had an interesting illustration of why it was even more important to be involved in politics than in the union. He would talk about Tate and Lyle plant, which he would say used to be the most unionised facility in Liverpool. As he would explain, "You couldn’t get into the place without a union card". But eventually, for various reasons, Tate and Lyle closed the plant and there was nothing the union organisation could do about it. And as George would conclude, "Where’s your union then?"

Ormskirk

Shortly after the election of 1959 the family moved to Ormskirk, and George and Irene again became active in the local labour party: in fact so active that when they moved to Cambridge in 1985 after George’s retirement the Ormskirk party presented them with a special certificate in recognition of all the work they had done.

Shortly before the 1974 general election the constituency party chose its parliamentary candidate. George and Irene didn’t take to the successful candidate at all, regarding him as unprincipled careerist of a type that has all too often gained position in the movement whilst having no real commitment to it. Someone for whom the movement was simply the route to a good job. After the meeting, he came up to George and spoke to him, wanting to make sure that he was onside. ‘You didn’t vote for me did you?’ he began. ‘No I didn’t’, George replied. ‘But will you work for me?’ asked the candidate, thinking of the election (it was a Conservative-held marginal seat at the time). ‘No I won’t’, said George, ‘But I’ll work for the Labour Party’. He didn’t trust the candidate at all, but the party had chosen him, so everybody had to do their best to get him elected, send him to Westminster as part of a Labour majority, and then see.

The candidate was Robert Kilroy-Silk. George had seen through him straight away – unfortunately many had been taken in. In George’s view it was no use screaming and shouting about it. One had to accept the decision, put forward one’s ideas and hope people would learn from experience. It’s a slow process, and nothing is guaranteed, but there are no short-cuts.

The candidate was Robert Kilroy-Silk. George had seen through him straight away – unfortunately many had been taken in. In George’s view it was no use screaming and shouting about it. One had to accept the decision, put forward one’s ideas and hope people would learn from experience. It’s a slow process, and nothing is guaranteed, but there are no short-cuts.

Kilroy-Silk

Kilroy-Silk was of course elected that year. I can still remember seeing Harold Wilson, whose old seat it had been, announcing triumphantly that night "we have won Ormskirk". The first time I can remember the town being mentioned on television. The next day there was a special programme on Newsnight (or whatever it was at the time) in which they had a special item on Kilroy-Silk who said that he expected to be prime minister in 15 years.

Trades Council

Both elements remind me of the story of one of George’s fellow members of the Liverpool Trades Council, a Communist Party member who, when Wilson was elected leader of the Labour Party in 1963 after Gaitskell’s death, suggested they should send him a telegram of congratulations. Wilson at the time had the image of a left winger. "Let’s see what he does first" said George. Years later the same person’s opinion had changed. "I’m disillusioned with Wilson," he said.

"Everyone’s disillusioned with Wilson. Even George is disillusioned with Wilson". Talk about a red rag to a bull (and of course George was a Taurus). As he reminded his brother unionist "in order to be disillusioned, you need to have had illusions in the first place."

As George would say when people accused him of being a cynic, "I’m not a cynic. I’m a realist".

But there was much more to George than trade unionism or politics.

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

It was also appropriate that he was born on the same day of the year as William Shakespeare and he had a deep love and understanding of his works and of many other areas of theatre, music, opera, literature and art.

Much if not most of what I know about any of these is because of what I learned from him. Given his lack of formal education, a great deal of his knowledge was self-taught or gleaned from non-traditional routes such as the courses he took in the army at the end of the war, when the powers-that-be organised such things to keep the soldiers busy before demobilisation.

One of his favourite stories was about the Italian university lecturer who used to take them to visit churches and the like. On one occasion this was during the referendum on the future of the monarchy. When the lecturer started to lead his group through a crowded church while the priest was addressing the congregation, most of the soldiers hung back. "Come on" said the lecturer. "He’s only telling them which way to vote".

Pier Head

One of the key things about George was his humour and wit, which he would often use to make an important point. I remember one occasion during some Liverpool Trades Council celebration involving a march at the Pier Head by the River Mersey, organised by the then head of the organisation Simon Fraser, a man with rather grandiose ideas but no equivalent capacity to put them into practice.

Two Mile Long Cable

In order to play some music, Simon had brought along a mains-powered record player. "Ah", said George, "that’s just the thing. All you need now is a portable power point or a cable two miles long".

And although the present state and future of the world bothered George, his own part in it did not. He was not a person to look back and chew over past decisions. And though he could be cautious in small ways – as Irene will tell you, it was difficult to persuade him to go any distance on holiday – once he had decided to do something he would go into it wholeheartedly. "If you can get him to chance his arm," she would say, "he will enjoy it."