This year sees the 40th anniversary of the May events of France 1968, which culminated in the biggest general strike in history, involving more than 10 million workers. TV programmes and newspaper columns will mark the occasion but few, if any, will give a real reflection of the role played by the main actors and actresses, the working class.

The movements of workers in 1968 shook capitalism and Stalinism to their very foundations, after many years in which ‘official society’ had poured scorn on the ideas of Marxism and revolution. Yet within a few weeks the contradictions riddling French society had erupted to the surface, so that all the conditions for a peaceful socialist transformation of society existed, except for one – a leadership capable of understanding events, explaining their implications and guiding the French workers to taking power into their own hands.

In 1958, President Charles De Gaulle came to power posing as the saviour of France, promising to cure France’s economic ills and win the war against the Algerian independence movement.

Claiming to stand ‘between capitalism and communism’ as a ‘third way’, De Gaulle, in reality, instituted a form of ‘parliamentary bonapartism.’ Lacking any real social base, he balanced between the classes.

Using state intervention in industry to benefit big business at the expense of the petty bourgeoisie, imposing strict censorship of the press and media, disregarding parliament and ruling by decree, he sought to save France for capitalism. The post war boom had been delayed in France, not least by the conscious policy of French capitalism to hold back the development of a strong working class. Nevertheless, the economy had developed significantly under De Gaulle. The working class had recovered from the defeats of the pre-war and immediate post-war periods. But economic growth had exacted a tremendous price. Unemployment had risen to 700,000 by 1968. The introduction of Value Added Tax, the deregulation of rents and a 45% rise in prices over the previous decade had eroded living standards. Low wages and an average 45-hour week imposed further strains, while three million lived in slums. The Economist described the interior of the Renault Billancourt Plant as "a sight from hell." Capitalist ‘progress’ meant intense pressures on the minds, sinews and nerves of workers.

Likewise, in the universities, the conditions faced by students were growing intolerable. A fourfold increase in student numbers over the previous 20 years, coupled with repressive college regimes, resulted in 75% of students failing to complete their courses. The social base on which De Gaulle’s regime rested was weak, indeed the social base for capitalism was growing rickety. The evidence for this was first demonstrated in the movement of the students – the ‘gilded youth’.

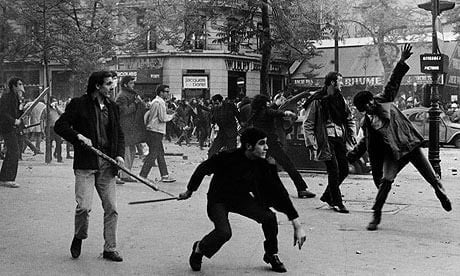

1968 saw student movements throughout the world. What tipped the balance in France, detonating the general strike, was the brutal response of De Gaulle. In early 1968 demonstrations against the outdated and restrictive education system resulted in the authorities calling in police and riot squads (the notorious CRS) to ‘put down’ the discontent.

Brutal Clampdown

In early May, a number of students from Nanterre University were to be tried for ‘disruptive behaviour’ in the University Courts. On May 2nd, the University Director closed the faculty, expecting trouble. The following day, a peaceful demonstration outside was attacked by the CRS. Lectures were suspended at other Paris universities fearing a repeat. As the temperature rose the university teachers’ union called a strike which was banned by the Education Minister, Peyrefitte.

On May 5th students arrested on previous demonstrations were jailed and fined. The strike in the universities spread to secondary schools. Each attempt to smash the movement by repression resulted in more anger and wider participation.

The next day a 60,000 strong demonstration through the Latin Quarter was brutally attacked by the CRS. Students were forced to set up barricades. Not since the rising of Parisian workers against the German army in 1944 had these defences been seen on the capital’s streets. The actions of the CRS provoked widespread anger, and support for the students. That night, 739 lay injured in Paris hospitals, while hundreds more found refuge in local residents’ homes.

The unease of the middle classes was reflected in the press. Polls showed 80% support for the students. Peyrefitte blamed a "handful of troublemakers". The Communist Party (CP), the biggest workers’ party at that time, denounced "groupuscules, Trotskyists, anarchists and CIA agents" in a disgraceful show of mimicry.

The next few days saw demonstrations, street fighting and more barricades. Young workers began to mingle with the growing student numbers. The CP leaders were taunted by demonstrators and banners demanded "police out of the Latin Quarter," "reopen the universities," "free our comrades" and "students’ and workers’ solidarity".

The Communist Party leaders expounded the theory that socialism was impossible in France until the living standards of workers in Stalinist Russia rose to the levels of Western Europe.

On the night on May 10th, the ‘Night of the Barricades’, 60 or more were built. Students tore up the cobbles, assisted by workers with pneumatic drills. The demonstrators were met with tear gas, CS gas and smoke bombs. Angry residents poured buckets of water out their windows so the students could wash their stinging eyes and skin. Gas seeped into the Metro, affecting passengers. In the aftermath, angry doctors demanded the police be prosecuted. A wave of revulsion and disgust pressured the leaders of the workers parties and the unions to call a one-day general strike for May 13th. Prime Minister Pompidou’s announcement of the reopening of the Sorbonne University and withdrawal of the police couldn’t stem the tide. The scene was set.

It is vital to understand that the one-day general strike and the titanic movement which followed did not drop from the sky, but was rooted in the conditions pertaining.

The trade union leaders hoped to dissipate workers’ anger and called the one day general strike to let off steam.

Although the initial response of French workers to the students’ call for support had been muted, deep discontent flowed through the working class. During late 1967 and early 1968 strikes and lock-outs had occurred in engineering, the car plants, steel industry, shipbuilding and the public sector. An estimated 80% of workers involved were outside of the trade union movement.

At the Renault Billancourt factory, there had been 80 cases of trade union action between March and May ’68. On Mayday, 100,000 had marched through Paris. A tense mood gripped the factories.

During the first week of May a printers’ strike threatened, Paris bus workers struck, sugar factory workers walked out, taxi and post office workers planned strike action. By May 7th the police trade unions were drawing up a list of demands, air traffic controllers threatened action, and a 24-hour strike took place at the Berliot lorry factory over bonus payments. Workers at the Weather Centre discussed taking action, striking iron ore miners blocked the Route Nationale motorway for an hour and occupations took place at a foundry and clothing company.

Mounting Pressure

Mounting pressure from the workers’ movement and widespread disgust with the activities of the police and CRS in trying to suppress the students had forced the workers’ leaders to shift their position. The CP leaders, who days previously had sniped at "groupuscules", were forced on May 11th, to call a 24-hour general strike around the demand for an end to repression.

Mitterand, then President of the Left Federation, after initially offering half-hearted support for the students, was calling for the creation of a provisional government by the end of May. The trade union leaders hoped to dissipate workers anger and called the one day general strike to let off steam.

But the general strike of May 13th, instead of heading off the movement, crystallised the workers’ anger and carried the struggle forward onto a higher level. One million marched through Paris with 20,000 stewards around the march from the CGT (Communist trade union federation) alone. 50,000 demonstrated in Marseilles, 60,000 in Lyons, 40,000 in Toulouse and 50,000 in Bordeaux. Yet only 4 million were organised in the trade unions. In Paris, the police stood aside; there was no rioting, no looting just a tide of angry workers, becoming aware of their power. The students left the march and occupied the Sorbonne and the Censier Annexe. The doors were flung open to workers; a no-holds barred discussion developed. A huge experiment in democracy began. Endless debates ensued, numerous committees sprang up. Soon most French universities were occupied. The students began to feel a sense of power, that they were leading a revolution. But real power lay in the movement of the working class, the decisive force in society.

The day after the general strike, 200 workers were on strike. Five days later on May 19th, two million were out. By May 21st, strike movements encompassed 10 million workers. Young workers at the Sud Aviation plant provided the spark. After a long running dispute with management, they became infected with the mood of the students’ struggle and the spectacle of the Paris demonstration. Beginning by spreading the strike to other parts of the factory, they then moved on to call for other factories’ support. Twenty managers were locked in their offices at the plant as loudspeakers played them the Internationale, so they might learn how to sing it!

On the 18th, strikes and occupations spread to Renault, the shipyards, the national theatres and the hospitals. The day after, all 60,000 Renault workers had downed tools and the six factories were occupied, guarded by mass pickets – with 3,000 at one plant. Marseilles and Le Havre ports were closed and 3,500 were attending daily strike meetings at Orly-Nord airport.

Despite the trade union leaders not calling a general strike, it grew like wildfire, touching every sector of industry and every corner of France, even to the women of the Folies Bergere. France was on the brink of revolution.

The Communist Trade Union Federation (CGT) leaders began to realise what was going on. 300,000 extra copies of Communist paper L’Humanite had been printed for the demonstration of May 13th. Now the official leaders tried to impose their own strike committees over the heads of the radicalised workers and youth. On May 17th L’Humanite saluted "the workers who have followed our call." But they had made no call to action. A clear attempt was being made to steer the movement into a ‘safe’ direction and pour cold water on the strike. Attempts were even made at strike-breaking. The CGT leaders talked of the movement as a "great tranquil force" arguing that "any talk of insurrection would change the character of the strike", which amounted to a recognition of the seismic shifts in society taking place.

Meanwhile the government hung suspended in mid-air. De Gaulle, on a state visit to Romania, was taunted as "leading a government in exile." The virus had even begun to infect the CRS (riot police) whose representatives warned they might not be able to prevent industrial action.

The Communist Party was in turmoil, reflecting the pressure of workers on the party which had traditionally been seen as the main workers’ party. 55,000 new members joined in 1968. Paradoxically, at a time when a genuine Marxist tendency could have developed rapidly in the CP and particularly in the Young Communist League, the so-called Trotskyists around Ernest Mandel had recently walked out of the YCL and set up their own little organisations, the PCI and JCR, in competition to the CP.

Bolshevik Party

The programme of the CP revolved around the call for democracy, harking back to the Popular Front policies of 1936. ‘Democracy first, socialism in the far distant future.’ Probably the most rigid, most Stalinist CP in Western Europe, the French CP had nothing in common with the Bolshevik Party of 1917. Decades of reformist degeneration stilted the leaders at a time when a decisive revolutionary leadership was vital. The pressure from below was manifested in an uncharacteristic call from CP General Secretary Waldeck Rochet for the "nationalisation of the big banks and monopolies", but no perspective or programme of campaign as to how this might be achieved was presented.

As the workers movement escalated, layers of the middle classes began to follow their lead. Theology students, magistrates, lawyers, museum curators and many others demonstrated, threatened strikes and began to question their role in society.

The action committees in the factories, offices and neighbourhoods began to link together. In Nantes, the strikers ran the city and introduced price controls and other reforms. Elements of ‘dual power’ developed. On one side the government and state apparatus, on the other the action committees led by the workers. The defenders of the old system were fighting against the workers struggling to find a way to the new – and forced to begin to reorganise society to meet their needs.

Scandalously, the CP and CGT leaders refused to call for national co-ordination of these committees. De Gaulle arrived back from Romania demanding action. In discussion with the police chief he called for the police to take the universities back from the students, but was warned sharply of the dangers of this action. "Blood will flow" was the reply.

French capitalism was looking into the abyss. Three of the four conditions outlined by Lenin for a successful revolution existed. The ruling class was split, unable to govern by the old methods and divided as to what policy to adopt. The working class was demonstrating a tremendous capacity to struggle. The strike grew day by day drawing in wider and wider layers.Thirdly, the middle classes were beginning to move behind the workers and could not be relied on as a social base for the regime or indeed capitalism. The fourth condition however was lacking – a revolutionary leadership of the working class, capable of explaining the tasks that the workers movement required to transform society.

De Gaulle’s Referendum

The leadership of the workers’ movement was hopelessly out of touch. The Wall Street Journal commented that "they were all part of the establishment, faced with a popular tide they had cause to fear." Whilst they sought an "acceptable solution", the Cannes Film Festival was stopped by strike action as were horse and motor racing and even golf competitions. The news was partly under the control of radio and TV journalists. All that was required in France ’68 was a Marxist leadership with a clear understanding of the way forward.

In true Bonapartist fashion De Gaulle called for a referendum on "participation". After narrowly surviving a censure motion in the French parliament two days before, De Gaulle faced a split party, sections of which demanded his resignation.

Then the government gave the order to storm the barricades. The night of May 24th was the most violent yet. 800 were arrested, 1500 injured. With this backdrop the trade unionleaders entered tripartite talks with the employers and government. In reality, the trade union leaders were negotiating with ghosts. Power lay in the lap of the workers’ leaders, whose hands were shackled to the old society.

The union leaders emerged delighted at their success. All workers would receive a minimum 7% pay rise. The statutory minimum wage was raised 33%. Some shop workers received 72% increases. Strikers were even given 50% of their salary for the periods they were occupying the factories. But when the leaders went to the factories they were booed and jeered. The workers understood the situation far better than their leaders. The CP leaders argued the movement was a struggle for wages, that the workers were not ‘ready for socialism.’ The movement had gone beyond merely economic demands – the question now was ‘who ran society’?

De Gaulle understood the situation. On May 29th, fleeing Paris he said, "The future depends not on us but on God." The strong man of France sought out the army commanders at Baden-Baden and demanded their support. At the same time half a million workers demonstrated in Paris, many carrying placards calling for a ‘people’s government’.

On May 30th De Gaulle returned, having been comforted by the army commanders. He called a general election for the 3rd week in June around the slogan, "me or chaos". A demonstration in his support was organized in Paris bringing contingents from all over France, the composition of which was overwhelmingly middle class and elderly, representing all the reactionary elements of French society. A bourgeois commentator wrote however, that, despite this demonstration, the balance of forces lay decisively in favour of the workers’ movement.

Tanks

Tanks and lorry loads of soldiers descended on the outskirts of Paris. De Gaulle had demanded army support for a rival government in the event of a revolution. But the events of the previous period had not left the army untouched. The army was made up of conscripts. A Times editorial asked, "Can De Gaulle use the army?" The answer it gave was yes, "But only once". Even this was not guaranteed since there are many examples of an army crumbling in the face of revolution.

De Gaulle had a gamble on his hands. By May 31st even the London Evening Standard was forced to recognise the CP had "all the levers of power in its hands" but lacked the intention to take power. A revolutionary situation does not last forever and the tide was beginning to turn.

Election Campaign

De Gaulle entered the election campaign leaving behind him a trail of sacked ministers and using the "red scare". On their part the CP leaders argued workers should return to work and negotiate with management. Their election platform failed to give a socialist position and amid disillusion with their role they lost 605,000 votes, the Left Federation of Mitterand lost 570,000 whilst De Gaulle gained 1,200,000. Despite the gerrymandering of electoral boundaries, which played a role in the defeat of the lefts, the major reason for their defeat was their political position. The CP even claimed the clothes of De Gaulle, portraying themselves as the ‘party of law and order’.

Many workers remained out on strike until the end of June but by then the movement was subsiding. A tremendous opportunity had been missed. Victory in France and the development of a healthy workers’ state would have been a shining example to the workers of the Stalinist and capitalist countries. The movement sent ripples internationally. Students throughout the world watched the events in France, sparking protests in Britain, Argentina and Italy among others.

In France, the employers attempted over a period of time to turn the screw back down on the workers. Victimisations and reprisals resulted in thousands of workers being sacked. But for De Gaulle victory was hollow. Wounded by the strike movement, he was eventually defeated in his referendum on ‘participation’ and regional government and resigned less than a year later.

The defeat of the movement had a marked effect on the French labour movement. Not until 1981 was Mitterand elected as president with a majority socialist government. The Socialist Party, formed shortly after the great strike, failed to carry through a fundamental change in French society, despite an ostensibly left programme on assuming office.

The events of May 1968 demonstrated the colossal potential power of the working class and the potential which exists on a world scale for the construction of a society freed from capitalism in which hunger, poverty and inequality could be abolished in France and internationally. As such it is not sufficient to ‘celebrate’ the events of 1968 but to learn from them in preparation for the movements of workers which will spring forth from the decay of capitalism on a world scale.

See also:

Audio File: 1968 – Year of Revolution (part 2)

By Alan Woods,

Friday, 16 May 2008

Audio File: 1968 – Year of Revolution (part 1) by Fred Weston,

Tuesday, 13 May 2008

1968: Remembering the Spirit of Revolution

By Rob Sewell,

Friday, 25 April 2008

The French Revolution of May 1968 – Part One

By Alan Woods,

Monday, 05 May 2008

The French Revolution of May 1968 – Part Two

By Alan Woods,

Friday, 02 May 2008