Britain’s housing crisis has gone from bad to worse. Across the country, tenants are being pushed to the brink, as landlords engage in a feeding frenzy of extortionate rent increases.

Shelter recently reported that millions of private tenants in England were “stretched to breaking point”, with almost 2.5 million renters either behind or constantly struggling to pay rent – an increase of 45% since April 2022.

And for those who can’t make their rent, eviction is an ever-looming threat. Almost one million low-income households across Britain fear eviction in the coming months.

Instability and anxiety

The Guardian recently published an article featuring interviews with tenants facing the threat of eviction. One was a single mum from South Devon, who had been renting her house for six years when she was informed her rent would increase by 20%.

The Guardian recently published an article featuring interviews with tenants facing the threat of eviction. One was a single mum from South Devon, who had been renting her house for six years when she was informed her rent would increase by 20%.

She attempted to negotiate for a smaller increase. Instead, in January, she received an eviction notice, as the owner wanted to sell the house so that they could buy another one in the Cotswolds. As another tenant explained:

“We had problems with the flat and had been emailing about repair issues for six months – mould, a bathroom leak, a bathroom tap, a bedroom door handle and broken windows. Instead of fixing it, they have told us we need to leave so they can renovate the flat and sell it. The landlord is from New Zealand, and is selling the entire block, seven flats in total.”

Clearly, for landlords, these properties and their occupants are nothing more than a cash cow to be milked. For tenants, however, these are homes; the foundation for their entire life.

In this dog-eat-dog system, landlords have the power to sell-up or evict tenants at a whim. This produces an enormous sense of instability and anxiety for renters, who effectively have no say in the matter.

Interest rates

One factor behind these out-of-control rent increases is the soaring cost of servicing mortgage debt. This has hit levels not seen in more than a decade, following the Bank of England raising its base rate 10 times in a row. This effectively makes borrowing more expensive for homeowners and businesses.

These interest rate rises are in theory supposed to bring inflation down. But what this means in practice is that landlords and firms pass their extra borrowing costs onto ordinary people. The result is that workers’ living costs are going up, not down, leading to misery for millions.

One tenant in Bristol, for example, was given four months’ notice to leave. In this period, they had their rent raised by £100 per month. Their landlord’s reasoning was that, due to being “heavily hit by the interest rate hike”, she could “no longer afford the mortgage she had on the place”.

The owner in question has several properties, and has just sold another one. She claimed, however, that she just “can’t afford to keep being a landlord”.

Workers are facing attacks from all sides. Not only are the bosses attacking pay, but landlords are also passing on their costs to tenants – all while making a tidy profit!

This highlights that it is not workers seeking wage rises who are responsible for inflation. In reality, it’s the other way around: workers are forced to demand pay rises simply to afford the bare minimum for survival.

Privatisation and profit

But this housing crisis is not simply the result of short-term, recent policies from the Bank of England or the Tory government. This crisis has been decades in the making.

But this housing crisis is not simply the result of short-term, recent policies from the Bank of England or the Tory government. This crisis has been decades in the making.

Before the 1980s, a much larger proportion of Britain’s housing stock was owned and managed by local councils. The right to affordable housing was a concession won by the working class after the Second World War, through struggle.

Council housing was far from perfect. But at least there was still some degree of public control over the quality and cost of housing.

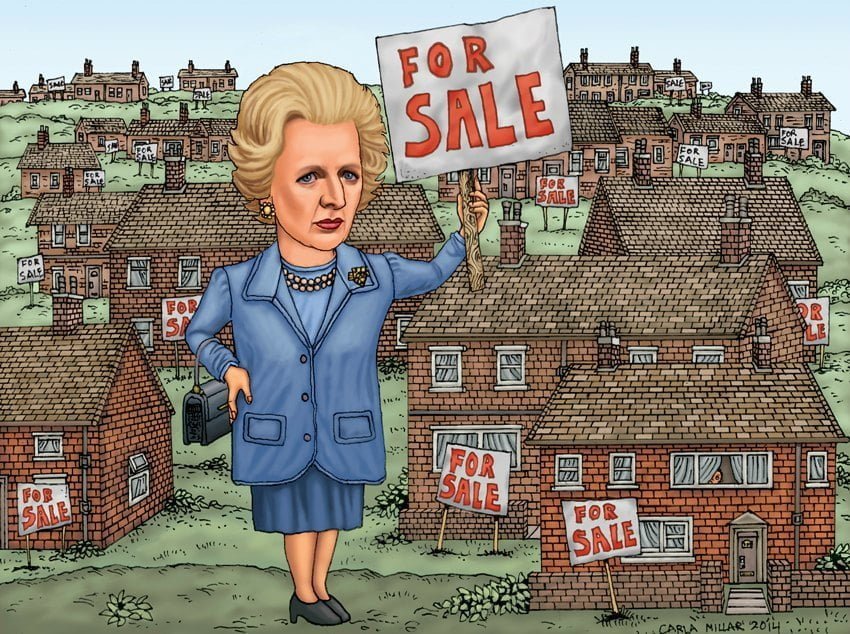

But under Thatcher this housing supply was sold off, as part of the transformation of Britain into a get-rich-quick rentier economy. Alongside this, housing regulations were loosened in favour of landlords and property developers. And schemes like ‘Buy to Let’ accelerated the privatisation of the UK housing stock.

It is precisely this – privatisation and profiteering – that is to blame for skyrocketing rents and prices, declining property standards, illegal subletting, and the spread of slum housing.

Rent controls

Local leaders in England – including those in London and Bristol – have been calling for central government to grant them powers to set rent controls in their areas. But Tory ministers have insisted they will do no such thing.

In response to this suggestion, housing minister Felicity Buchan stated categorically that: “The government does not support the introduction of rent controls in the private rental sector.”

She went on to say that rent caps would “discourage investment, lead to declining property standards, and may encourage illegal subletting”.

Considering at least a quarter of Tory MPs are landlords, their opposition to rent controls shouldn’t come as a surprise. These ladies and gentlemen are looking out for themselves and their rich backers.

With millions fearing eviction, having to choose between heating or eating, a rent freeze would be a welcome and necessary immediate step to alleviate the pressure on working-class tenants.

We must stress, however, that such a measure can only offer a temporary reprieve, as long as housing remains in the hands of private landlords and big management companies. This has been highlighted in Scotland, where the government announced a total rent freeze and ban on evictions last September.

Even though the scheme has been extended to September this year, from this month it will allow landlords to increase rents by up to 3%, and to carry out evictions in extreme circumstances.

Socialist policies

These attempts to tinker around the edges, and to curb the worst excesses of parasitic landlords, are not enough. Only bold socialist policies can address the misery and destitution facing tenants across the country.

These attempts to tinker around the edges, and to curb the worst excesses of parasitic landlords, are not enough. Only bold socialist policies can address the misery and destitution facing tenants across the country.

To genuinely solve the crisis facing renters, we must expropriate the big landlords, management firms, and property developers as a matter of urgency. Empty properties owned by speculators and investors should be requisitioned. And housing associations and their stock must be brought back under public ownership and democratic control.

Furthermore, we should nationalise the banks and major construction companies, in order to implement a crash programme of house-building, and to bring existing homes up to a decent standard.

On this basis, millions of new council houses could be built; the scourge of landlordism eliminated; and a decent home could be guaranteed to everyone.