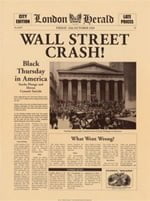

The Great

Depression: then and now

The 1920s were good years for the world economy. They were years of

boom. Boom and speculation go together like strawberries and cream, and there

was speculation aplenty as well. In such a period of ‘irrational exuberance’

the illusion spreads that the good times will go on for ever. Sound familiar? On the eve of the great 1929 stock exchange

collapse, a journalist asked a speculator how so much money was being made on

the market. This was the reply: "One investor buys General Motors at

$100" (he meant a GM share) "sells to another at $150, who sells it

to a third at $200. Everyone makes money". This seems pure magic, but for

a while it can work. In a ‘bull market’ as in 1925-29 nearly all share prices

go up and up. Over those years US industrial shares trebled in price! We all know what happened next.

Another feature

of the 1920s boom was the massive global imbalances. Briefly Anglo-French

imperialism had emerged militarily victorious from the First World War, but

economically wounded and forced to borrow from the USA to cover their war

debts. The only real victor was the USA, which had showed itself to be the

mightiest economic and military power in the world. American bankers, as creditors

to the British and French, demanded their pound of flesh. These governments in turn decided the only

way to pay the USA was by squeezing defeated German capitalism, demanding war

reparations from the stricken German economy.

Reparations

flowed out from Germany, and then flowed straight out of Britain and France to

the USA. So the upshot was that the poor subsidised the rich.

The Great

Depression of 1929-33 produced male unemployment at one time of more than 30%

in Germany whose economy was totally dependent on the health of the world

economy. But if Germany could not pay reparations, how could Britain and France

pay their debts to the USA? So the Depression destroyed this mad flow of money,

and with it the delicate balance of the global economy. The collapse of world

trade (falling from a factor of 10 in 1929 to 3 in 1933) in turn further

impacted on the major national economies. But as ever it was the small and poor

nations that fared the worst. This remains the case today – as we shall see.

Bubbles

There are

startling similarities between the boom of the 1920s and its inevitable sequel

in bust from 1929 to 1933 and the present decade. As we all know the boom in

the advanced capitalist countries was fuelled by a housing price bubble – a

situation where prices go up because people are buying and people are buying

because prices are going up. Huge amounts of fictitious capital, pure paper

wealth, were created. For instance the annual output of the world in the year

2007 at the end of the boom was about $64trn. At the same time the amount of

financial assets in the world was $196trn. And the amount of total trades in

that year was $1,168trn – seventeen times as much as was produced. This was

literally a paper merry-go-round.

These pieces of

paper were ‘valued’ at what they were likely to deliver in the future. As

anyone who knows that what goes up must come down would realise, these

expectations of ever-expanding wealth were impossible to achieve since this

wealth ultimately had to be generated in the real capitalist profit-making

economy. So the unstable boom eventually came to an end with a sickening

crunch.

That much of the

capital built up over the boom was fictitious is shown by one stark fact. The

total value of quoted shares on the global stock exchanges was $63trn in

October 2007. A year later in November 2008 it was $31trn. More than half the

value of the world’s bourses had gone up in smoke! Though we have seen a ‘bull’

market in shares since March 2009 on most exchanges, this fact illustrates the

phantom nature of this wealth. The same applied to the price of houses. In the

early years of this millennium they were seen as not bricks and mortar but

appreciating assets. Not any more. All kinds of other paper assets, created by

financial ‘innovation’ during the boom, were also on the slide.

Financial Crisis

This in turn hit

the banks and credit institutions. Their lending was based on holding assets

which turned out not to be assets at all. This was catastrophic, particularly

since the financial institutions, in order to fill their boots in time of boom,

had ‘leveraged’ themselves by thirty times or more. This technical expression

means that they had lent thirty times more money than they actually had. Rather

than holding the loans on their books the official banks bundled them up and

passed them on as fantastically complex financial assets.

But these assets

were by no means ‘out of sight, out of mind.’ They passed into the hands of the

secondary banking sector. The central institutions of this shadowy nether world

of finance are the hedge funds. Hedge funds are melting away. Those that

handled more than $1bn (small change to them!) fell by 40% last year. They are

disappearing because they are losing money on the recondite financial

institutions they bought from the main banks. And their losses mean the

official banking sector has to take a heavy hit. Lehman Brothers went under in

2008 because they were more exposed to the dodgy dealings and had more links to

the secondary banking sector than the other major players

Inter-bank lending,

the essential oil of the world’s monetary system, ground to a halt. No bank

would lend to any other because they didn’t know what their own assets were

worth, if anything, and they realised that all the other banks were in the same

position.

Martin Wolf sums up the

present imbalances in the world economy (Financial Times 08.03.09):

“How did the world

arrive here? A big part of the answer is that the era of liberalisation

contained seeds of its own downfall: this was also a period of massive growth

in the scale and profitability of the financial sector, of frenetic financial

innovation, of growing global macroeconomic imbalances, of huge household

borrowing and of bubbles in asset prices.

“In the US, core of the global market economy and centre of the current

storm, the aggregate debt of the financial sector jumped from 22 per cent of

gross domestic product in 1981 to 117 per cent by the third quarter of 2008. In

the UK, with its heavy reliance on financial activity, gross debt of the

financial sector reached almost 250 per cent of GDP…

“These huge flows of capital, on top of the traditional surpluses of a

number of high-income countries and the burgeoning surpluses of oil exporters,

largely ended up in a small number of high-income countries and particularly in

the US. At the peak, America absorbed about 70 per cent of the rest of the

world’s surplus savings.

“Meanwhile, inside the US the ratio of household debt to GDP rose from 66

per cent in 1997 to 100 per cent a decade later. Even bigger jumps in household

indebtedness occurred in the UK. These surges in household debt were supported,

in turn, by highly elastic and innovative financial systems and, in the US, by

government programmes.

“Throughout, the financial sector innovated ceaselessly. Warren Buffett, the

legendary investor, described derivatives as ‘financial weapons of mass

destruction’. He was proved at least partly right. In the 2000s, the ‘shadow

banking system’ emerged and traditional banking was largely replaced by the

originate-and-distribute model of securitisation via constructions such as

collateralised debt obligations. This model blew up in 2007.”

Eastern economies ‘emerging’

– into ruin

How has the

world recession impacted on the poor nations? We shall examine the fate of the

former Stalinist countries in particular. These Eastern European economies saw

an unprecedented economic collapse with the downfall of the Stalinist regimes

after 1989. Russia, for instance, saw the biggest fall in production since the

invasion of the Mongols, who left pyramids of skulls in their wake. In the

early years of the present millennium these countries reached rock bottom and

began to bounce back. They re-emerged as hapless client states of the major

capitalist powers.

Most of the East

and Central European economies have been growing at around 5% a year since the

past boom gathered speed in the early years of the century. As a result many of

their political leaders have developed a cargo boat cult of capitalism and

tried to pass it on to the population. They have seen their future as

‘emerging’ capitalist economies. They have copied the worst excesses of the

advanced capitalist economies. And the present world recession has brought them

to their knees.

Accepting that

their fate lies with capitalism, these economies have relied on trade with the

West. Their ‘comparative advantage’ lies in wage differentials with the North

American and Western European economies of the order of 7:1. Canny capitalists

in Western Europe located more and more production processes in the East,

hollowing out manufacture in the West as a result.

Basic

manufacturing processes are being transferred to the East. The Ukraine, for

instance is a massive exporter of iron and steel to Western Europe. You might

have thought that the Eastern countries would enjoy an export surplus with the

West. The opposite has been the case. They were on a treadmill – running fast

and going nowhere. East and Central European countries have run deficits of the

order of 5-10% of GDP with the West. Latvia managed 23% at one time and

Bulgaria 27%. This means these countries were spending about £5 for every £4

they were earning. This can not go on! These current account deficits were only

covered by capital inflows from the imperialist heartlands. Capital inflows

were as much as 5-8% of GDP and funded about 70% of East and Central Europe’s

deficit.

So corresponding

to the outflow of basic industrial production from the East has been vast

capital inflows. In effect the Eastern countries have been borrowing the money

from the West – to buy the West’s products! Suddenly, just when the money is

needed most, the tap has been turned off. Capital inflows have collapsed.

According to the Financial Times (28.01.09) “The Institute for International

Finance predicts that net private sector capital flows to emerging markets will

be no more than $165bn this year, less than half the $466bn inflow in 2008 and

just one fifth of the amount sent in the peak year of 2007.” In the case of the

Central and East European six nations inflows will fall from $161.9bn in 2008

to $59.5bn this year.

Dependent growth

Now comes the

collapse of this dependent growth. To take just one statistic – Russian

industrial production fell by 20% in the month of January 2009 alone. These are

figures only matched by the economic wipe-out of 1929-33.

In the meantime

nations such as the USA and Britain have been in effect living at the expense

of the rest of the world, running trade deficits with other nations and

borrowing from them in order to maintain consumption levels. For instance the

American trade deficit with China is closely matched by the inflow of Chinese

money into the USA. So China is lending America the money to buy its exports –

but China is a much poorer country than the USA. This daisy chain of payments

is remarkably similar to the pattern of monetary flows of the 1920s. The

destruction of these capital movements in the Depression did much to make the

slump deeper by drying up world trade.

Could this happen again? Sure it could.

In recent years

the deficits in the household sector, government sector, financial sector and

with the rest of the world run by countries such as Britain and the USA have

spiralled as the world boom became more and more obviously based on

speculation. Similar deficits and speculation is mirrored in the Eastern

countries. There has been a housing bubble in the Baltic countries. Banks,

learning from the West, have invented exotic financial instruments and floated

such deals as mortgages denominated in yen, since Japanese interest rates were

low. In Hungary they preferred mortgages in Swiss francs

All this was

fine as long as the exchange rate remained stable. But instability in

capitalism means instability in exchange rates. This instability in turn is a

product of the unevenness that is an inevitable feature of capitalist

development. These imbalances are ultimately unsustainable. Their ‘resolution’

is having catastrophic consequences for the people of the region

Imbalances

All this is a

repetition on a larger scale of the imbalances of the interwar period. So the

Chinese have been kind enough to lend the Americans the money to keep on buying

Chinese goods in the form of acquitting US government securities. Clearly this

can’t go on for ever! But the situation is likely to persist until the Chinese government

foresees a wholesale depreciation of the dollar. Yet, as long as the American

economy runs these huge deficits, the counterpart is bound to be a net outflow

of dollars to buy foreign goods. And if speculators perceive that the USA is

living at the expense of the rest of the world by printing dollars, a flight

from the US currency is inevitable.

Once again

imbalances become causes of contention in a crisis. The flashpoint of national

conflicts, as capitalist nations try to unload the effects of the crisis on to

other nations as well as their own working class, is bound to be the exchange

rate.

The ECE

countries are small economies. That means that they are dependent on the fate

of the major imperialist powers. The same is true of their currencies. After

all, who in Britain but a pub quiz nerd has heard of the Ukrainian Hyrvania?

Usually these nations have fixed their currencies against the dollar or the

euro. The transmission mechanism of crisis from one country to another works

through trade and monetary flows. These currencies naturally are a flash point

of the stresses and imbalances that are tested to the limit in the recession.

These fixed

rates of exchange can be washed away by a giant wave of global money, with

catastrophic effects on the economy. While their exports are cheaper as a

result of the depreciation, each good sold abroad earns less foreign currency

and their debts become more and more expensive to service in the national

money. And those exotic mortgages denominated in Japanese yen and Swiss francs

don’t look such a bright idea when the local money tanks against the major

trading currencies of the world.

Financiers are

essentially gamblers. They would bet on two flies climbing up a wall. And they

also bet on the prospects of countries going bust. These bets are called

sovereign credit default swaps. From this point of view Ukraine looks like a

derby winner. Their CDS rate is 3,700 base points (these are in effect the odds

on a default) compared with 1,000 for Latvia and 560 for Hungary, two other

high risk economies. The money men (and women) are gambling that a whole nation

is unable to pay its bills. And they complacently await a sovereign default – a

whole country going under – so they can collect their winnings.

Iceland has

already in effect defaulted as a nation. Last October it was discovered that

the wizards of high finance had produced a situation that Icelandic banks owed

six times as much as the people of Iceland produce in a year. In Western

countries when the banks turned up their toes, finance ministers rushed to save

them on the grounds that they were ‘too big to fail.’ But the Icelandic banks

were ‘too big to save’! Naturally the people of Iceland are to pay for the

crimes and stupidities of their bankers.

The knock-on effects

of the crisis have already hit Hungary, Lithuania and Latvia. Other countries

in the region are also in the firing line. Governments are going down like

ninepins. There is no end in sight to the economic and political turmoil. In

Iceland the left has been swept to power by a ‘pots and pans’ revolution, but

they have been given the job of pulling the chestnuts out of the fire for

capitalism and making the cuts demanded by the International Monetary Fund.

IMF

The IMF is the

financial sheriff. It stabilises capitalist economies at the expense of the

common people. For instance Estonia’s deficit with the West has fallen to 15%

of GDP. In order to cut their coat according to their cloth, GDP must fall by

15%. That is the IMF’s remedy.

Like the spectre

at the feast the IMF always turns up when things look bleak, and helps make

them worse. What do they propose? They demand that countries at their mercy cut

government spending. Latvia has pledged to cut $913m (5% of GDP), a huge sum

for a country of only 2 million people. One country after another is now lined

up outside the head’s office for chastisement.

Readers will

notice that countries under the cosh of recession such as Britain and the USA

allow government deficits to balloon. They are reluctant to cut government

spending as they know it will make the recession worse. Yet that is exactly

what the IMF is insisting upon. The IMF is deliberately making unemployment,

and the plight of the poor, worse. What sort of medicine is that? It represents

the interests of the capitalist class in the dominant imperialist countries.

The Observer

(26.04.09) reports from the economists blowing the whistle on the IMF. “An analysis of the new wave of loans, by Mark

Weisbrot and colleagues from the Washington-based Centre for Economic Policy

Research (CEPR), finds that every one contains pro-cyclical policies.” (i.e. it

makes the slump worse) “While the IMF has led the argument for large-scale

fiscal stimulus in the rich world to kick-start economic growth, at the same

time, the CEPR argues it is still forcing the countries that come to it for

emergency loans to cut back on spending and reduce budget deficits.

For example, Pakistan had to promise to cut its deficit

from 7.4% of GDP last year to 4.2% this year. ‘While this might be a desirable

goal, it is questionable whether this reduction should all be done this year,

when the economy is suffering from a number of external shocks that are

reducing private demand,’ Weisbrot and his co-authors say…” But who cares about

the Pakistani poor? Not the IMF.

“Duncan Green, head of

research at Oxfam, says that whatever the message from HQ in Washington, IMF

staff on the ground can’t help handing out tough medicine: ‘It’s in their

DNA.’”

At the G20 in

the beginning of April the big capitalist nations pledged with great fanfare to

increase the IMF’s funding to ‘help out’ the poor nations who are at the sharp

edge of the crisis. Amid silent recrimination the rich nations have been unable

to agree as to who is to stump up the cash. It is a measure of the depth of the

crisis that the IMF, and the rich countries it represents, has lost control of

the situation.

Political Repercussions

All in all things look bad

for the ‘emerging economies.’ This is already having predictable political

repercussions. According to Jason Burke (Observer 18.01.09): “Eastern

Europe is heading for a violent "spring of discontent", according to

experts in the region who fear that the global economic downturn is generating

a dangerous popular backlash on the streets.

Hit increasingly hard by the financial crisis, countries such as Bulgaria, Rumania and the Baltic states face deep

political destabilisation and social strife, as well as an increase in racial

tension…

“According to the most recent estimates, the economies of some eastern

European countries, after posting double-digit growth for nearly a decade, will

contract by up to 5% this year, with inflation peaking at more than 13%. Many fear

Romania, which joined the European Union with

Bulgaria in 2007, may be the next to suffer major breakdowns in public order.

‘In a few months there will be people in the streets, that much is certain,’

said Luca Niculescu, a media executive in Bucharest. ‘Every day we hear about

another factory shutting or moving overseas. There is a new government that has

not shown itself too effective. We have got used to very high growth rates.

It’s an explosive cocktail…’

“Marius Oprea, security adviser to the last Romanian government, said the

economic crisis would mean ‘serious problems for the middle class.’” (and not

just them!) “He added: ‘There will be a fall in tax revenue which will lead to

major problems for state budgets. The numbers of state employees will also be

cut right back and their salaries will be worth less and less…’”

Dr Jonathan Eyal, a regional specialist at the Royal United Services

Institute thinktank in London, said eastern European countries were

ill-equipped to deal with the impact of the global downturn and risked ‘social

meltdown’.

‘These are often fragile economies … with brittle political structures,

political parties that are not very well formed and weak institutions. They are

ill-prepared for what has hit them," Eyal said. "Last year it was the

core western European countries which were shaky; now it is the weaker

periphery that are getting the full blast of the crisis.’”