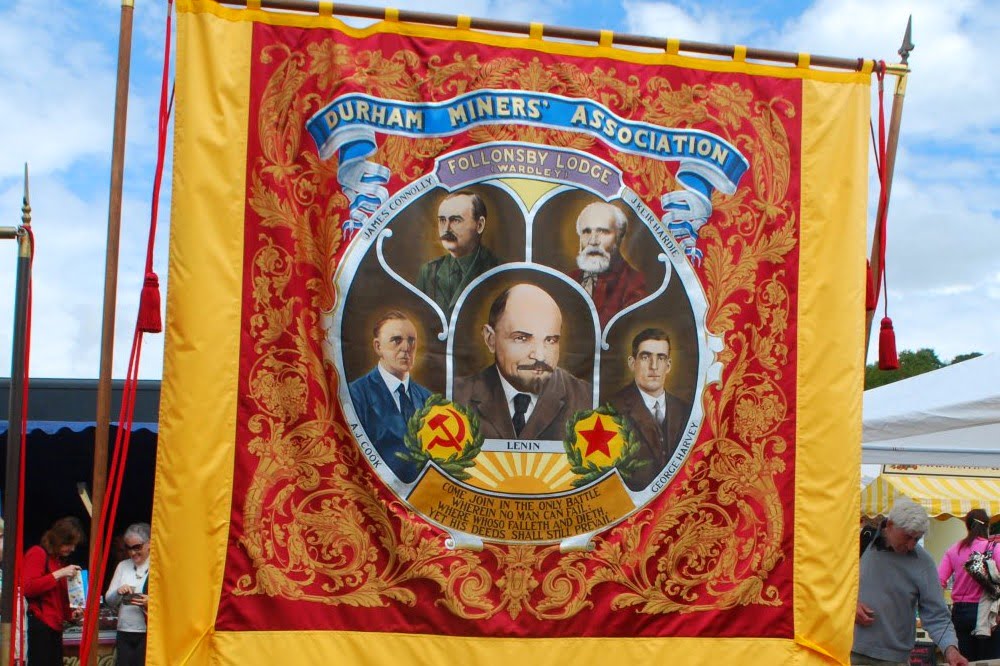

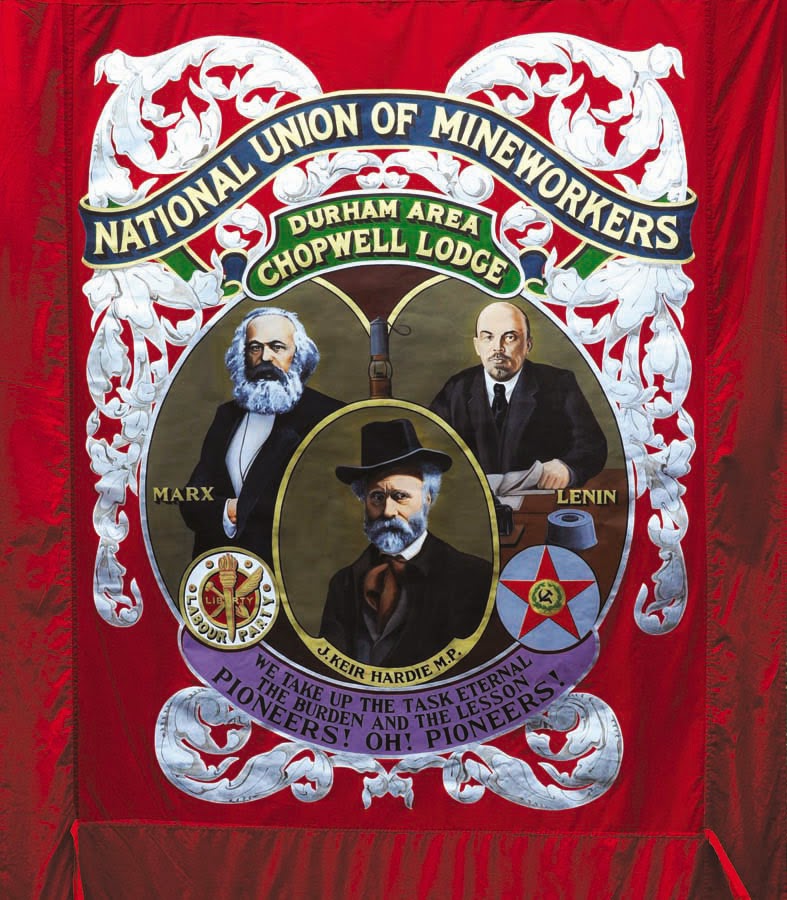

This year’s Durham Miners’ Gala takes place 35 years after the beginning of the Great Miners’ Strike of 1984-85. We celebrate the struggles and traditions of the miners and their families – both the historic struggles, and the struggles of workers and young people today.

In the late 1970s and early 80s, NUM (National Union of Minerworkers) members could often be seen wearing Saltley Gate ties. This was to celebrate their victory over the Heath Tory Government in 1972, when miners successfully closed down Saltley Gates coking depot in Birmingham by the use of mass picketing. Miners from Wales and Yorkshire were joined by trades unionists from the West Midlands. Little did anyone know that the Tories were planning a wide-ranging revenge.

Thatcher was elected in 1979. She went on to use the ‘Ridley Report’ as her blueprint for a new attack on organised labour. Written by a then right-wing Tory MP, Nicholas Ridley, the report was designed to break the coherence and resilience of the trades unions. This, in turn, was to prepare the ground for an economic policy called ‘monetarism’.

The aim was to shift economic power and control from nationalised industries to the private sector, and to make the hiring and firing of workers easier for the bosses. All of this was designed to boost the profits of big business.

The Ridley Report suggested that a ‘weaker’ trade union be targeted first. And so a national steel strike began in early 1980. I can well remember the seemingly endless picket lines along the Don Valley between Sheffield and Rotherham. Despite the strike becoming increasingly effective, the ISTC (Iron and Steel Trades Confederation – steelworkers trade union) leadership capitulated and the strike was lost.

Preparation

Having practiced on the steelworkers, the NUM were next on the list for Thatcher. Historically, mining unions were strong as a result of collective working conditions underground. In Britain, the NUM were seen by all as the vanguard of the trade union movement.

Having practiced on the steelworkers, the NUM were next on the list for Thatcher. Historically, mining unions were strong as a result of collective working conditions underground. In Britain, the NUM were seen by all as the vanguard of the trade union movement.

The government prepared in advance of taking on the miners. Coal stocks were built up; power stations were changed to burn fuels other than coal. Police numbers were increased and police pay and conditions were improved. Although it was considered illegal at the time, a de facto national police force was set up. Seamus Milne, in his book The Enemy Within, suggests that the NUM was infiltrated at the highest level by the forces of the state.

Then, early in 1984, a dispute was manufactured by the government, commencing at Cortonwood Colliery in South Yorkshire. The Tories announced plans to close a number of pits. The NUM resisted. And so the Great Strike began.

Initially the NUM concentrated its efforts at shutting down pits that were working in the Nottinghamshire coalfield. The police, using intelligence from all over Britain, were able to stop miners from getting to pits in Nottinghamshire. Many were stopped outside Nottinghamshire. Indeed, Kent miners were stopped by the police at the Dartford Tunnel, in order to keep them from getting to Nottinghamshire.

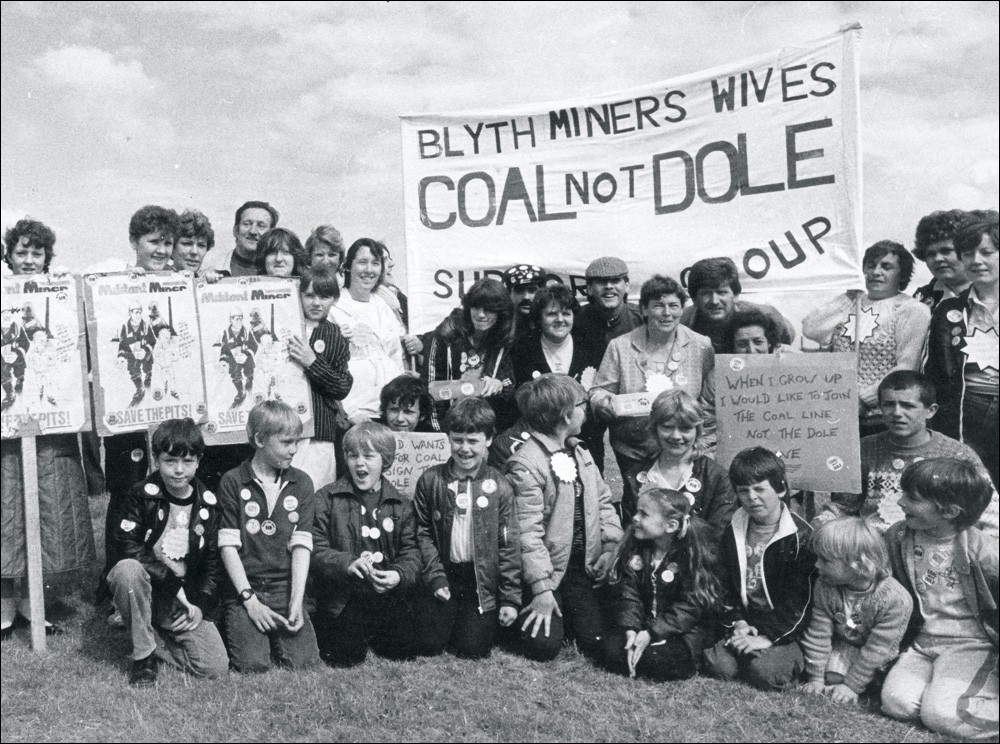

The miners received massive support and solidarity from other workers during the strike. Collections of food and money kept the strike going. Soup kitchens were set up to feed striking miners families. From these came a mass movement of working class women: the miners wives.

Orgreave

The Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign rightly campaigns against the violence and excesses of the state during the Battle of Orgreave. The BBC coverage of Orgreave at the time showed miners throwing rocks and bottles at police, followed by a charge by mounted police at the miners. A year or two later, the BBC quietly admitted that they had shown these events in the wrong order.

The Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign rightly campaigns against the violence and excesses of the state during the Battle of Orgreave. The BBC coverage of Orgreave at the time showed miners throwing rocks and bottles at police, followed by a charge by mounted police at the miners. A year or two later, the BBC quietly admitted that they had shown these events in the wrong order.

As well as batons, riot shields, and protective helmets, police horses were repeatedly driven into lines of unprotected miners. This police brutality was not confined to Orgreave, but also happened in a number of mining villages in Yorkshire – Fitzwilliam and Stainforth being just two.

The NUM leader Arthur Scargill, who had risen to prominence during the strikes in 1972 and 1974, was hoping for a repeat of the victory at Saltley Gates. He was not able to achieve it, as the state had prepared meticulously to prevent this from happening. As Scargill said at the time, miners in t-shirts and trainers were faced with thousands of well-armed and well-protected police.

Much more recently, it has been revealed that the Tory government was willing to consider deploying the army against the NUM, as well as using live bullets.

Determination

The miners and their communities stood firm for a year, in a magnificent show of determination. Thanks to the soup kitchens and the support of other workers, the miners were kept fed. And many local businesses deferred payments for goods and services.

The miners and their communities stood firm for a year, in a magnificent show of determination. Thanks to the soup kitchens and the support of other workers, the miners were kept fed. And many local businesses deferred payments for goods and services.

The response from the majority of the leaders of the labour movement – and particularly miner’s son and leader of the Labour Party, Neil Kinnock – was not to support the miners but to undermine them. Arthur Scargill was subjected to press vilification and attacks by leaders of the right wing of the movement.

There were weaknesses of the NUM ‘left’ prior to the strike, particularly in Nottinghamshire, as well as divisions over the question of a national ballot for strike action. But despite this, there is no doubt that the leaders of the NUM knew about the Ridley Report and knew what was likely to happen. As such, they prepared as best they could.

It is to the eternal shame of the labour and trade union leaders at the time – with a few honourable exceptions – that, as in 1926, the miners were left to stand alone.

Struggles

This defeat cleared the way for the onset of privatisation, anti-union legislation, and, ultimately, Thatcher’s proudest creation: Tony Blair and New Labour. Barnsley, which had 18 mines and depots in its metropolitan area in 1984, was rapidly reduced to none. It became the drug capital of Yorkshire, as narcotics filled the economic wasteland caused by the destruction of Britain’s deep-mined coal industry.

This defeat cleared the way for the onset of privatisation, anti-union legislation, and, ultimately, Thatcher’s proudest creation: Tony Blair and New Labour. Barnsley, which had 18 mines and depots in its metropolitan area in 1984, was rapidly reduced to none. It became the drug capital of Yorkshire, as narcotics filled the economic wasteland caused by the destruction of Britain’s deep-mined coal industry.

Today, at events such as the Durham Miners’ Gala, we remember these struggles of the past. But we also prepare for the struggles that lie ahead – in particular, the fight for a Labour government with a socialist programme. Only the socialist transformation of society can offer a real future for working-class communities and our young people.