Why

the Kremlin invaded

The movement in Czechoslovakia

was nowhere as highly developed as the

movement in Hungary or Poland

in 1956. There were no workers’ councils, nor were the workers armed, as in Hungary, where

the Russians intervened.

But even in Poland

in 1956, there was a general strike and an insurrection in Poznan!

Yet the Russians allowed Gomulka to control the situation by means of reforms in Poland in

1956, but could not allow Dubcek to do the same thing in Czechoslovakia

in 1968. Why?

The answer is to be found, partly, in the changed international balance

of class forces since 1956. The intervening period has seen the

monolith of world Stalinism shattered into pieces by a series of splits

along national lines. In a very striking manner, Trotsky’s prognosis of

1923 has been

confirmed in the 1960s: that the theory

of "socialism in a single country", which substituted the narrow,

national interests of

the Russian bureaucracy for those of the international working class,

would inevitably

result in the nationalist degeneration of the Communist International.

Since the events of 1956, the Stalinist bloc has suffered the split-off of China,

which has led, not to the

creation of two Stalinist

camps, but to the opening up

of a whole spectrum of

"national roads to socialism".

With the Sino-Soviet split, the policies of the Rumanian and

Yugoslav bureaucracies, Gomulka’s "Polish Road", etc. the stranglehold

of the

Russian bureaucracy

over the other bureaucracies

and also over the CPs of

the West has greatly weakened.

The extent of the degeneration

can be gauged from the

frantic attempts of the

Russian

bureaucracy to drum up support for

a world meeting of CPs for the

purpose of a solemn excommunication

of China.

Compare this to the ease with which Stalin was able to expel Yugoslavia from

Cominform and the

difference is clear. Nowadays,

even the Castro bureaucracy

in Cuba,

resting on the

narrowest basis of any Stalinist

state, can afford to assert its

"own" road to "Socialism",

as can be seen from the

purge of the pro-Moscow wing of the Cuban CP in January of this year.

Even more significant was the Budapest Conference of CPs in March.

Only 67 Parties even bothered to attend, as against 81 in 1960.

Cuba, Yugoslavia, N. Korea and N. Vietnam

were absent. Rumania walked

out; of the Asian

Communist Parties only the

pro-Moscow Indian Communist Party attended.

In the past decade, Stalinism has suffered a series of blows which have undermined its power

and prestige internationally.

No longer can the "Moscow

Line" command the blind

fanatical

adherence it had before

the

war.

But far more important even than this fact have been the developments amongst the masses of

Eastern Europe and Russia itself.

The ferment

among the Russian writers

is

only the tip of the iceberg as far as the discontent of the masses in Russia itself is

concerned.

It is an amazing comment on the weakness of the bureaucratic regime in Russia

that 50 years after the revolution

a whole period of so-called

"de-Stalinisation" and "Thaw",

after all the promises about

"building Communism in 20

years",

it has to sentence writers to hard labour for the crime of demanding the implementation of the Soviet Constitution. But far more significant than

the writers’ trial

earlier this year was the stream of protests by Soviet intellectuals that followed the sentences.

The grandson of the famous Soviet diplomat Litvinov issued an open letter condemning the trial, and signed his own name

and address in

open defiance of the secret

police. The son of the Soviet general Yakir, murdered by Stalin in the

infamous purges, issued a

similar

protest, in which he warned that Stalinism still existed and called for the re-habilitation of Leon Trotsky.

Yakir also signed his name and address. After the protests, the Bureaucracy clamped down hard in an attempt to gag the

intelligentsia. The works

of Alexander Solzhenitsyn who only a few years ago was hailed by the Soviet press as "a new Dostoevsky" have been

banned. Solzhenitsyn

had been leading the campaign

against censorship and for freedom

of the arts in Russia.

The developments in Czechoslovakia

could not be tolerated because of the effect they would have upon the Soviet people, starting with the intelligentsia. The

effect upon the Ukraine, which borders on Slovakia and which has been seething with discontent in the last

eighteen months,

would be particularly serious.

The abolition of the censorship in Czechoslovakia would

leave the Russian

bureaucracy without any

grounds

to resist the insistent

clamour

of a growing number of Soviet

intellectuals to remove the dead hand of bureaucratic control from literature and the arts. But far more serious would be

the effect on the working

class itself.

The free airing of opinions in the press would provide a focal point for organised expressions

of discontent, leading

inevitably in the direction of a new programme and a new party. Already in Russia

there are hundreds

and thousands of underground study circles, where workers read and draw their

own conclusions from the

works of Lenin, which are

still

distributed in editions of hundreds of thousands in the Soviet Union.

The

tragedy of Czechoslovakia

was that the Czech people found themselves leaderless, disarmed and unprepared.

The Dubcek clique preferred to see the country occupied rather than arm the

working class. For all his brave words, Dubcek was prepared to eat dirt, rather

than risk sparking off the spontaneous mass movement of the working class.

None of Lenin’s safeguards remained

The glaring contrasts between Soviet reality and the ideas of Lenin

is becoming clear to all. The 1919 Programme of the

Bolshevik Party, drawn up

mainly by Lenin, laid down the

following basic pre-requisites for workers’ power, not "under

Socialism", not "under Communism"-but in the very first stages of

Soviet power, in the period of transition from capitalism to socialism:

-

Free and democratic

elections, with the right of recall -

No official to receive a

higher wage than a skilled worker -

No standing army, but the armed people

-

No permanent bureaucracy: "Every cook should be able to be Prime Minister".

Of these

elementary safeguards of workers’ democracy, not one remains in force in Russia

and Eastern Europe today. That is why the movement of the

workers in the East inevitably takes up the demand for a return to Lenin, not

back to capitalism, but for the purging of the Soviet state of bureaucrats,

careerists and parasites, for a genuine socialist workers’ democracy.

In Czechoslovakia, as in Hungary in 1956 (where the workers

actually set up workers’ councils to rule the country, Soviets in all but name)

the working class would undoubtedly have moved in this direction. Already, in

at least one Czech journal, the idea of Soviets (i.e. genuine, democratic

organs of workers’ power) had been put forward. In the course of events, the

workers would have learned by their own experience the need to by-pass the

limitations imposed on them by the Dubcek clique.

The

Hungarian workers in 1956 came late on the scene, after the stage had been set

by the movement of the students and intellectuals, but when they did intervene,

they went farther than the "liberal" bureaucratic Nagy and Kadar had forseen.

The movement transcended the "calm", "dignified", "constitutional" nonsense of

the Nagys and Dubceks and became a genuine workers’ revolution; not a social counter-revolution to overthrow

the Socialist property relations, but a political

revolution to oust the bureaucracy and establish a healthy democratic workers’

state.

That

movement of the Hungarian workers was only crushed by the tanks of the Russian

bureaucracy at tremendous cost and effort. Now, in 1968, they were faced with

an awkward choice: to intervene would mean yet another terrible blow to the

power and prestige of world Stalinism; not to intervene would probably lead to

an even more dangerous situation for the bureaucracy, and one which will not

stop at the borders of Czechoslovakia.

The

invasion bears all the hallmarks of a sudden, panic move. The behaviour of the

Russian leaders over the past months has been inconsistent, vacillating,

dilatory. There may even be some substance to the speculation of bourgeois

commentators about a split in the bureaucracy.

At all

events, the invasion of Czechoslovakia

must not be seen as proof of the strength of the Russian bureaucracy but as a

move dictated by fear, a move that demonstrates beyond doubt the extremely

shaky basis upon which Russian and East European Stalinism exists.

On the face

of it, the appearance of Russian tanks in the streets of Prague

spelt immediate and inevitable defeat of the movement in Czechoslovakia.

But such a conclusion is fundamentally false. Of course, if one approaches the

question from a purely military angle, then all talk of resistance by the

Czechs to the mighty army of Soviet Russia, with its overwhelming superiority

of men and resources, would be ridiculous.

But for

Marxists, military factors by themselves cannot be decisive in war. If that

were the case, then the young Soviet republic, which at one stage was reduced

to two provinces, around Moscow and Petrograd, would have been crushed by the twenty-one

armies of intervention. But this did not happen.

Why were

Lenin and the Bolsheviks able to emerge victorious from the Civil war against

overwhelming odds? The answer lies in

the clear internationalist position of the Bolsheviks and the class appeals

that were made to the workers in uniform of the foreign armies of intervention.

The result of the Bolshevik propaganda and fraternisation on the already

demoralised troops led to mutinies in the armies of intervention which became

"infected" with "Bolshevik influenza".

A genuine

Leninist leadership would have prepared the Czech people for the eventuality of

an invasion, both politically and militarily. The confrontation of the Red Army

by an armed working class, organised in Soviets, would have had a tremendous

effect on the Russian workers in uniform.

As it was, numerous eye-witness accounts told of the bewilderment

and demoralisation of the Warsaw Fact troops, as the realisation dawned on them

that they had been duped by their leaders. There were instances of Russian

troops breaking down and weeping in the streets, protesting that they did not

even knew they were in Czechoslovakia,

that they did not wish to fight the Czech workers, etc. In such circumstances,

fraternisation based on clear class, internationalist lines would undoubtedly

have led to massive disaffection in the Red Army.

Even

without this, it is a measure of the complete demoralisation of the troops that

whole units had to be withdrawn after one week of occupation. But no army, no matter how demoralised, can

be expected to mutiny unless a strong alternative is clearly posed.

The Czech workers and students showed their

instinctive grasp of the need to fraternise. But mere passive resistance is not enough. The interventionist

troops should have been made to feel the absolute determination of the Czech

people to fight to the death if necessary to defend their gains. They should

have been confronted with a force so implacable as to encourage them to disobey

the officer with his pistol at their back. Without such a confrontation, the

officer caste can always force the workers in uniform into line with the threat

of the firing squad.

Also, in

relation to the propaganda used by the Czechs, much of it was of a nationalist

kind that would have no appeal to the Russian troops. Slogans like "Ivan go

home", while undoubtedly having a demoralizing effect, would not be capable of

winning the foreign workers in uniform as did the internationalist propaganda

of Bolshevism.

The tragedy

of Czechoslovakia

was that, at the crucial moment, the Czech people found themselves leaderless,

disarmed and unprepared. The perfidy and cowardice of the Dubcek clique which

preferred to see the country occupied rather than arm the working class, is a

clear indication of the real interests of this group. For all his brave words,

Dubcek was prepared to eat dirt, rather than risk sparking off the spontaneous

mass movement of the working class.

The workers will grasp the lessons of 1968

It is a

measure of the cowardice of the Czech bureaucracy, and its fear of the workers,

that even industrial action was ruled out, except for a one-hour stoppage. The

French events demonstrated how quickly a "calm", "dignified" strike (i.e. a

strike controlled and restricted from above) can develop into a revolutionary

movement.

In the

course of a general strike, workers’ councils emerge, embryo organs of workers’

rule, and that eventuality could not be allowed by the bureaucracy. It is

characteristic of the ‘liberal’ bureaucracy that they used the only remaining

weapons in their hands-the so-called "free" radio stations, as a means of

appealing for "calm" and "dignity"-i.e. as a means of preventing all resistance

to the invasion.

Undoubtedly

the Soviet intervention is a defeat for the Czech working class and for the

whole movement in the direction of political revolution in the East. The

Russian bureaucracy clearly realises that it is impossible to put the clock

back completely and restore the Novotny clique, and is prepared to permit the

continuation of "liberalization"-from above, and strictly under control. Dubcek

was dragged off, manacled to Moscow

and grilled by his "fraternal Soviet comrades", who presented him with an

alternative: do a deal or go to jail.

And Dubcek,

that courageous ‘liberal’, who solemnly swore to his people that there was no

question of going back on the gains that had been made, took the only

‘honorable’ solution-and returned to Prague! All talk of withdrawing Soviet

troops is so much dust thrown in the eyes of the Czech workers. In fact, all

that will happen is that troops will disappear from the public eye-perhaps from

the cities altogether. But they must remain, as safeguard against the

Czechoslovak workers.

Already there are reports of some 800 Russian agents operating in government offices in Czechoslovakia,

as they did formerly under Stalin. A tight rein will be kept on Dubcek and friends, in case they give way to pressure

from below once more.

A number of "reformers" who have been compromised by their statements in recent months have been sacked.

Censorship has been restored. Ominously Pravda has called for the arrest of some 40,000 ‘young counter-revolutionary

thugs’. Doubtless, the arrests and deportations have already begun. Crowds of intellectuals have

fled the country. Unfortunately,

the workers, as always,

have no such easy escape

routes;

they must stay and suffer the consequences.

The immediate effect of the invasion on the Czech workers will

clearly be one of demoralisation and disillusionment. With

all the strategic points occupied, with all the levers of power in the

hands of Soviet officer caste,

no resistance is possible at

this stage, although the

series

of provocations staged by the Russians may provoke clashes in which the

Czech workers, leaderless and unorganised, will suffer a bloody defeat.

But in spite of the temporary demoralisation, the Czech workers will have learned important lessons from the present

events. The experience

of the reality of Dubcek’s "reforms" will push the workers in the direction of a new alternative.

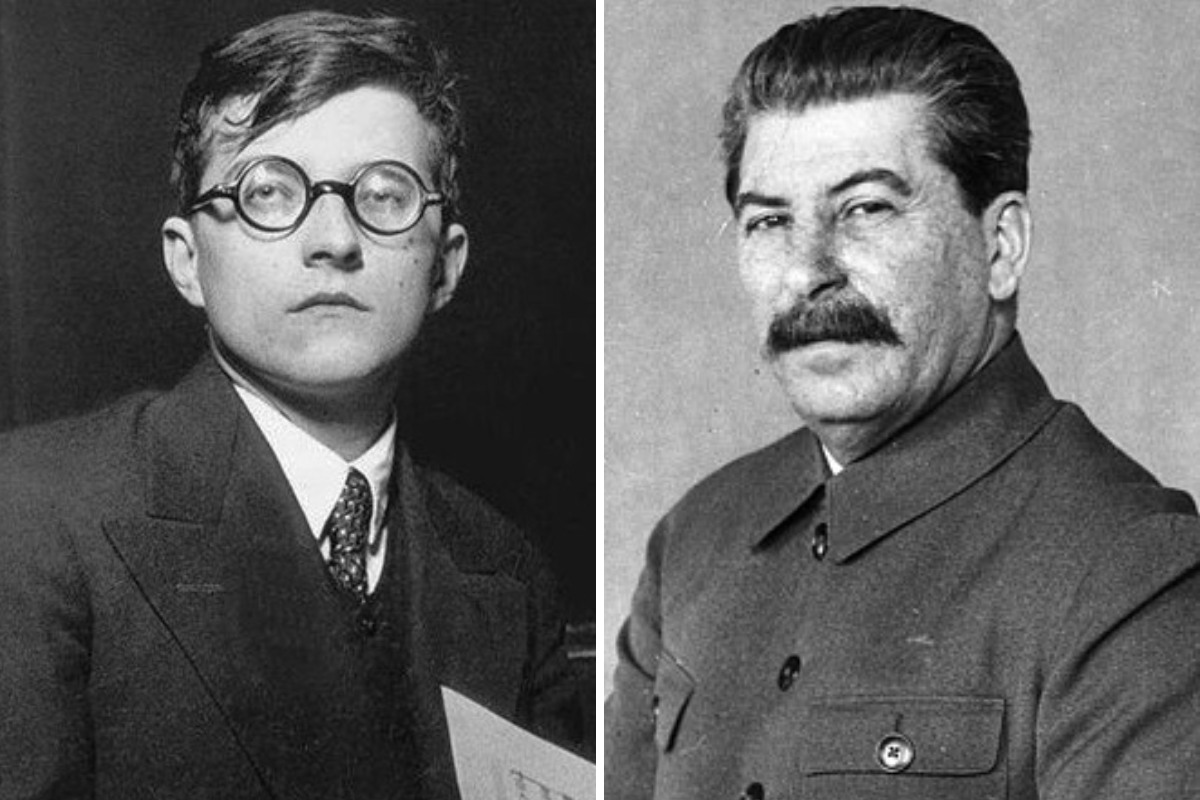

Already, during the invasion itself, slogans appeared such as "Lenin wake up, Brezhnev has gone mad". In one

demonstration in Yugoslavia, two

placards were carried,

one of them with a portrait of Lenin and a caption: "He would never have done this", the other of Stalin, which read:

"This is what he would have

done".

Without doubt, certain sections among the workers and students of Czechoslovakia will

already be groping

forward to a new anti-bureaucratic programme, a programme which can only be

based on the

democratic ideas of Lenin and the Bolsheviks. The present mood of defeat will give way to a new movement on a higher

level.

Even bourgeois commentators understand that the decisive force in

Czechoslovakia has not

yet had its say. A

recent article in the Sunday Times (4 September) summed up the

situation well: "Paradoxically intellectuals began the liberation

movement with little

worker support and now the

workers are showing the

strongest determination while the intellectuals run for the border with

their prudently acquired exit visas. Maybe there

will be a government

in exile, but it will be

less

relevant than a campaign of resistance launched and conducted by the

workers."

[To be continued …]

See also:

Czechoslovakia (1968): Stalinism rocked by crisis – Part One by Alan Woods (June 9, 2008)

Czechoslovakia 1968: ‘Lenin wake up, Brezhnev has gone mad’ by Alan Woods (May 18, 2000)

Dual power in France – A Militant leaflet, May 1968

Revolutionary days – May 1968, a personal memoir by Alan Woods (May 13, 2008)

The French Revolution of May 1968 – Part One by Alan Woods (May 1, 2008)

The French Revolution of May 1968 – Part Two by Alan Woods (May 1, 2008)

The French revolution has begun by Ted Grant (August 1968)

[Audio] 1968 – Year of Revolution by Alan Woods (May 21, 2008)

[Audio] Italy 1969: the Hot Autumn by Fred Weston (May 13, 2008)