The English Revolution of the 17th Century stands as one of the first great bourgeois revolutions in history. In only a few decades, it shattered the rotting feudal system and paved the way for the development of capitalism worldwide. For Marxists, these events are full of lessons.

We are often told that English democracy is the product of a peaceful, gradual agreement between King and Nation. And indeed, that the English Revolution was no revolution at all, simply a bloody squabble over religion that went too far (and was nicely resolved a decade later in the Restoration).

But the truth is, as Trotsky wrote, that Parliamentarianism was not “born on the Thames by a peaceful evolution”, nor was it the fruit of the “free foresight of a single monarch”, but in fact was “the result of a struggle that lasted for ages, in which one of these kings left his head at the crossroads”.

The Parliamentarians waged a revolutionary war against the King, driven forward by and clad in religious zeal. Their victory resulted in the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, as well as the establishment of a republic: the Commonwealth.

The defeat of the Crown was a historical necessity; the inevitable outcome of the rottenness of the old feudal order. And yet, even as Charles’ head was struck from his shoulders, his executors had no clear idea of what they would put in place of the absolutist monarchy. This would have to be worked out in the years and decades to follow.

Presbyterians, Puritans, and Independents within the Long Parliament – the parliament that sat during the years of the war – would find themselves at loggerheads around this question. Some sought a compromise with the king, and indeed all the institutions of feudalism. Some sought to go further, advocating for the establishment of a radical, puritan republic.

Weaving through these events is Oliver Cromwell, a cavalry commander who ended up playing the role of both stalwart leader of the revolution, and defender of private property.

World turned upside down

Britain during Charles’ repressive reign was a hotbed of dissent. Those found guilty of ‘sedition’– religious or otherwise – were publicly flogged and imprisoned. This only spurred on radicals of all stripes, who put up with any humiliation in their quest to establish the ‘Kingdom of Heaven’ on earth. The whole nation was a tinderbox waiting to explode.

Lenin once described revolutions as “festivals of the oppressed and the exploited”. This certainly holds true for the English Revolution.

Radical religious sects flourished in this period. The streets were awash with pamphlets and preachers detailing utopian societies that should be constructed. They identified the struggle for the right to freedom of religion with the struggle against aristocracy, the king, the church, and the whole rotten order.

In the white heat of the revolution, the bourgeoisie was able to place itself at the head of the masses, in the fight for what they coined the ‘Good Old Cause’. But when Charles was captured in 1646 and the dust settled, the class divisions within the revolutionary camp began to sharpen. The question now posed was what society should be built, and who should run it?

Centuries of religious dominance in society meant that the class antagonisms of the revolution were cloaked in the guise of religion. Religious factions can be understood as early political parties, each expressing varied class interests.

The idle aristocracy predominantly associated with the Catholic-lite High Anglican Church. Fighting against this in Parliament were the Presbyterians, representing the conservative big bourgeois, as well as the Puritans and Independents, representing the radical layers of the petty bourgeoisie.

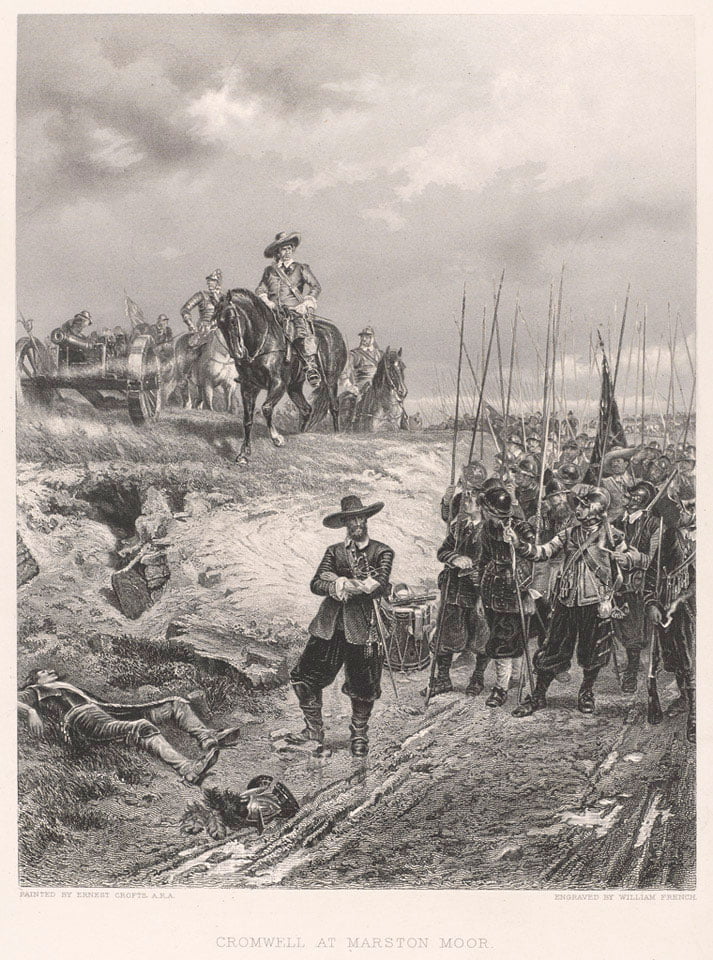

New Model Army

In order to win the war, Parliament had raised the first genuinely professional standing army seen in Britain in a thousand years, the New Model Army (NMA).

In the feudal period, all armies had been militias raised by local lords, and paid mercenaries. But now a single army, under one flag and with one uniform, was raised up and trained.

They were recruited from the most radical layers in society, and were all the more dangerous because they were fighting for something. As Cromwell once said: “I will raise such men as have the fear of God before them and make some conscience of what they do; and I warrant you they will not be beaten.”

Bringing together these layers into a tight-knit unit of collective struggle, which promoted freedom of debate, turned the army into a hotbed of radical democratic ideas. This was the first genuinely revolutionary army in history, combining radicalism with military prowess.

Undoubtedly this army was decisive in the Parliamentarian victory. But under conditions of peace, this now became very dangerous for the conservative Presbyterians in the Long Parliament. Having been the force that crushed the Royalists through waging a revolutionary war, the army naturally began to assert its own radical interests.

This clashed with the Presbyterians, who sought compromise with the King. Having slapped the King on the wrist, the big bourgeois were keen to put the whole conflict to bed in order to focus on their own landed properties and commercial interests. As we shall see, they saw danger to their property in pressing further with the revolution.

Cromwell’s army of radicals was an imminent threat to their authority. Having served its purpose in winning the war, they now needed it disbanded, at any cost.

Deadlock

The question of ‘which way forward’ was posed all the more sharply when Charles escaped from custody. This prompted a second (shorter) civil war, which ended in another parliamentary victory in 1648. The old ruling class had been defeated; its system shattered. And yet the new ruling class was totally split.

As it became clearer that compromise with Charles was not on the table, the majority in the Long Parliament still sought some kind of deal, creating a stalemate.

The paralysis of the Long Parliament revealed that what seemed to be the new state, set up to govern the country, turned out to hold no power at all.

Engels once explained that, in the final analysis, the state can be reduced to special bodies of armed men in defence of definite property relations. Nothing reveals the truth of this more than the events that followed.

Only the NMA, and its de facto leader, Oliver Cromwell, held such power. Cromwell understood this perfectly, and so was sure to purchase the soldiers’ loyalty by agitating around the issue of pay. Meanwhile, the Long Parliament was fighting a rearguard battle, trying desperately to disband the NMA.

This backfired. At the end of 1648, Colonel Pride of the NMA surrounded the Parliament and barred the Presbyterian MPs from entry, essentially banishing the big bourgeois from political power.

What was left would be termed the ‘Rump Parliament’. The big bourgeois and landowners, who were naturally conservative, needed to be taken out of power for their own good, in order to carry the revolution to its logical conclusion.

Just months after Pride’s Purge, on 30 January 1649, King Charles I was executed. With this, the stage had been set for the domination of the sword over parliament.

It was necessary to use the power of the army to break the deadlock and move the revolution forward. It would not be Colonel Pride that would pick up that mantle, however, but Oliver Cromwell.

Over the next decade, Cromwell was to blaze a trail of bourgeois reformation, completely upending the old order. He used the army to strike blows against both the conservative elements of the bourgeois and the old aristocracy – but also the radical elements who got too big for their army boots. England would never be the same.

Bonapartism

This phenomenon, the domination of the sword over society – emerging from a deadlock in the class struggle – represents what Marxists describe as ‘Bonapartism’, where the state balances between the classes and strikes blows on both sides.

But, as Trotsky explained: “The sabre has no independent programme… [and] represents in the social sense, always and at all epochs, the government of the strongest and firmest part of the exploiters.”

The NMA, under Cromwell, represented the tool of the most clear-sighted and decisive elements of the revolutionary bourgeoisie.

In order for Cromwell to use the army in this way, however, he first had to purge it of its dangerous elements. The most radical of these were the Levellers, a revolutionary democratic current with a lot of influence amongst the rank and file.

Led by ‘Agitators’ (their elected representatives) in the army, they had drafted the Agreement of the People, calling for: freedom of worship; legal equality for all men; and the right to vote for all men aged 21 and over.

Many of the demands first put forward by this agreement would later be replicated in the People’s Charter of 1838.

But Cromwell did not intend to enfranchise every man in England – only the bourgeois in whose interests the revolution had been made. And he understood the risks of letting the revolutionary tide run out of his control. A crackdown followed, with leaders either executed or shipped out to Ireland.

The resulting Leveller rebellion (the Banbury mutiny) was swiftly crushed by a force led by Cromwell personally.

To a bourgeois historian, such an apparent change of heart may seem nonsensical, perhaps attributed to Cromwell simply being a megalomaniac. Such a superficial analysis tells us nothing.

This was precisely Cromwell’s historic role, to carve out a path between the classes in order to clear away any obstacles to the bourgeois revolution.

Kingdom of the bourgeoisie

With the radicals put to heel, the Rump Parliament, under Cromwell’s watchful eye, carried out many of the tasks of sweeping away the old feudal fetters that were blocking the development of capitalism. One of the first acts of the Rump in 1649 declared that:

“You are to use all Good wayes and meanes for the securing advancement and the encouragement of the trade of England and Ireland, and the dominions to them belonging.”

Royal monopolies were broken up, and merchants allowed to invest wherever they saw fit. The feudal particularism that had long acted as a straitjacket to the nascent bourgeoisie was cast aside.

Vast tracts of land that were expropriated from Royalists and the Church during the war were auctioned off, often to wealthy merchants and rich landlords who would then carry out enclosures and develop capitalist agriculture on the freed-up land. This was a deliberate policy, a key element in the development of capitalism.

The 1651 Navigation Act asserted the Commonwealth’s monopoly over its shipping and trade, bringing it to war with the Dutch Republic. The Commonwealth’s victory would act as the central plank of the future British Empire, allowing for the unbridled expansion of capitalism across the seas.

The 1649 conquest of Ireland saw the country fully subjugated in just four years, with Cromwell returning after the first. It was here that Britain consolidated its domination over its first colony, and honed the brutal means of divide and rule that it would export across the globe and use to dominate its colonies with an iron fist.

In reality, the ‘Kingdom of Heaven’ that the revolutionaries were building proved decisively to be the kingdom of the bourgeoisie.

Crisis in the Rump

Whilst Pride’s Purge cleared the most obstinate layers of the Parliament and allowed for many of the tasks of the revolution to be achieved, the political crisis of the past would soon rear its head once more.

The Rump proved to be notoriously corrupt, with the war offering a plethora of opportunities for profiteering and plundering of the state. It was immensely unpopular amongst both the public, who read all about the various scandals in the press, and the army, who were frequently shortchanged when it came to pay.

The army demanded that a new parliament be called, elected on a broader suffrage than before. To maintain his balancing act, Cromwell was keen to oblige.

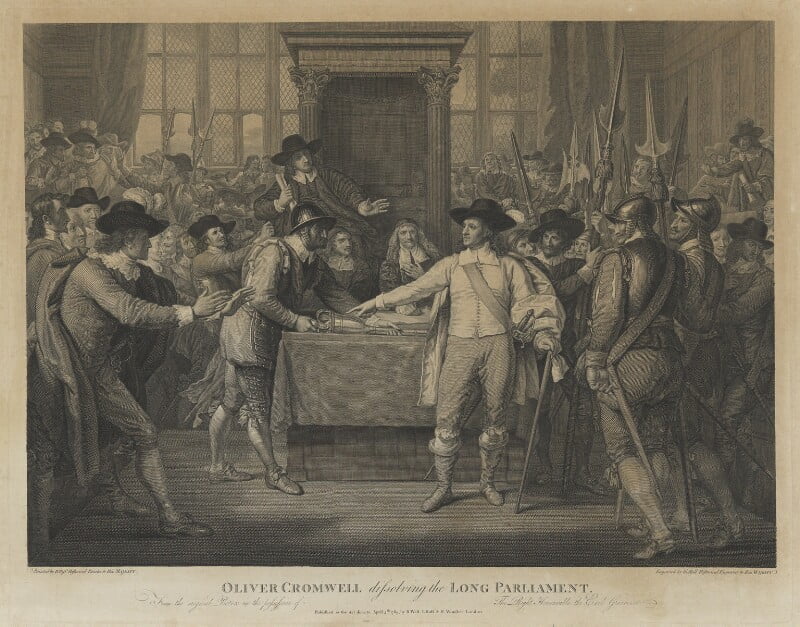

The Rump was always intended to be a temporary solution, promising to produce a new constitution and then dissolve itself. But, on 20 April 1653, it resolved not to dissolve and decided that it would oversee its own re-election.

Cromwell responded with a fiery speech, followed by a troop of musketmen who escorted out the MPs. As they passed by Cromwell, he insulted each one for their sins, saying to one that “ye have no more Religion than my horse!”

Once more Cromwell would wield the sword decisively – this time to sweep away a rotten parliament that had outlived the progressive role that it once held.

Despite the theatrics of the event, it did little to solve the underlying issue: the new class contradictions which had been unleashed by the revolution.

Praise God!

What came next was a nominated assembly of 140 people, selected by the army grandees on Cromwell’s request. This would be known as the ‘Barebones Parliament’, named after one of its members, Praise-God Barebones, notable for his intense religious fervour.

Whilst the majority of the assembly was conservative, there was a very energetic minority that quickly got carried away with its radical bourgeois programme. The most notable debate was around the question of tithes, the tax levied to fund the clergy, a key pillar in the maintenance of the feudal system.

Despite the abolition of the episcopacy, the hierarchical power of the bishops over the church, tithes remained. The most radical of the Puritans wished for them to be abolished and for complete freedom of religious association to be established.

When leaning on the radicals, Cromwell had alluded to this in the past. However, to abolish tithes proved a step too far.

The bourgeoisie saw in the prospect of the abolition of tithes a threat to all property. The conservatives accused the Barebones faction of “endeavouring to take away their properties by taking away the law, to overthrow the ministry by taking away tithes and settling nothing in their rooms”.

The familiar splits quickly paralysed the Barebones Parliament. This time, it would be the conservative majority which would march to Whitehall to relinquish powers back to Cromwell.

And so, on 12 December 1653, for the second time that year, Cromwell would utilise the army to dissolve the gridlocked parliament.

Oliver Cromwell, saviour of property

By 16 December 1653, Cromwell had been proclaimed Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. When being sworn in, he pledged to rule “upon such a basis and foundation as by the blessing of God might be lasting, secure property, and answer those great ends of religion and liberty so long contended for”.

The dissolution of the Barebones Parliament and the establishment of the dictatorship of one man shattered any remaining illusions as to what the ‘Good Old Cause’ was really about. Cromwell had taken the revolution through all barriers. Now it was time to hold it back.

Commenting on this, Engels would remark that “Cromwell is Robespierre and Napoleon rolled into one”.

His personal dictatorship, in which he, as Lord Protector, assumed more powers than any King, marked the end of the English Revolution.

Cromwell was not ‘consciously’ a bourgeois revolutionary. Like everyone else, he thought in terms of religion. Regardless of this, he was able to best embody the historic necessity of capitalist development – answering decisively a question that had been posed many times over the previous 100 years.

Despite the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, following Cromwell’s death two years before, things could never go back to how they were. The bourgeoisie remained firmly in the driving seat.

Two traditions

Despite attempts to downplay the significance of the Commonwealth, it was an integral period in establishing the foundations of British capitalism. In just eleven years, the British bourgeoisie had hammered into it the traditions and methods that would allow it to dominate the globe. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that its dominant position would begin to crumble.

A second tradition also flourished in this period, however: the revolutionary tradition. Groups such as the Levellers fought heroically to push the revolution as far as they could.

These groups were crushed, not due to lack of courage, but due to the low level of the productive forces. They consisted of the lowest levels of the petty bourgeoisie. They did not hold the power of the whole economy in their hands, as the proletariat of today does. In fact, the proletariat existed only in an embryonic form, as was the case with industry.

The conditions for a higher form of society, for socialism, now exist in abundance. The proletariat has left its embryonic stage, and now exists as a truly international class, billions strong.

Whereas the revolution of the 17th century was – and only ever could be – bourgeois, the revolution of the 21st century will be firmly proletarian.

Rather than replacing one exploitative elite with another, such a revolution will shatter the foundations of class society altogether, laying the basis for a communist society.

The traditions of the English working class lie not with ‘reformism’, and pacifism of all stripes, but with the revolutionaries of the New Model Army. This will be proven in the coming decades, which will turn the world upside down once again.