Introduction

The initial

trigger for the writing of this document was the Sino-Soviet split, its

importance for the world Communist movement at the time, and its significance

for the forces of genuine Marxism, the Trotskyists. In the first place Ted

declares that the split confirms Trotsky’s brilliant prediction, “That the

theory of ‘socialism in one country’ would lead inevitably to the degeneration

on nationalist lines of the parties of the Communist International.”

Secondly the

split was important for the course of the colonial revolution, a huge movement

shaking the world at the time. This was a movement whose course Marxists had to

analyse and understand. It produced an entirely new world situation, not

predicted by Trotsky. Here are the new features identified by Ted.

“The failure

of the revolution in the West, the degeneration of Stalinism, the failure of

successive waves of the social revolution in Western Europe, the thwarting of

the social revolution in the West and the expansion and consolidation of

Stalinism in the East, have been the world background on which the

revolutionary awakening of the colonial peoples has been taking place.”

Ted

naturally looked at the colonial revolution in terms of Trotsky’s theory of

permanent revolution. The core of the theory of permanent revolution is the

recognition that the bourgeoisie in the colonial and ex-colonial countries are

incapable of taking society forward and establishing genuine independence from

imperialist domination. Yet this was the central task posed by the colonial

revolution. These tasks, Trotsky predicted, fell to the working class to carry

out. Unfortunately the working class was under the influence of reformists and

Stalinists, who urged them not to take the power but mobilise behind the

non-existent ‘revolutionary national bourgeoisie.’

The impasse

in society produced by this paralysis allowed the state to apparently rise

above the classes and assume a certain independence. Marxists call this

bonapartism. Nevertheless in the last analysis the state always defends a

certain form of property relations. So we can have bourgeois bonapartism defending

capitalism or proletarian bonapartism – regimes in the image of Stalinism.

| Gamal Abdel Nasser |

In the document

Ted speculates as to whether Nasser would embark on the path of proletarian

bonapartism. It is now known that Nasser wanted Egypt to go down that road, but

was dissuaded by Brezhnev, who feared that the appearance of Egypt in the

Stalinist camp would upset the global balance of forces with the USA and the

West.

In Algeria,

Ben Bella was also very close to the Russians. This called the class nature of

Algerian society into question. In 1964 he was made a Hero of the Soviet Union.

But in 1965 Ben Bella was overthrown by Boumedienne. Though the significance of

this was not immediately apparent, over time Boumedienne was able to lead

Algeria firmly into the capitalist camp.

The collapse

of the Soviet Union led inevitably to the collapse of its satellite countries

in what is called the ‘third world.’ On August 12th we published an

article by Matt Wells, which analysed precisely the distorted development of

the colonial revolution in the case of Ethiopia (Ethiopia: which way forward?). Today we publish a short article on

the case of Benin. Ted Grant identified Benin as a case of proletarian

bonapartism in another document, ‘The Colonial Revolution and the Deformed

Workers’ States’ 1987.

In Benin, Kerekou certainly seems to have had a fine

instinct for the art of self-advancement and self-preservation. From a not very

radical background in 1972 he suddenly embraced Stalinism in 1974. Just as

smoothly, he foresaw the breakup of his mentor country and led the way back to

capitalism in 1989. Finally he took over as President of Benin again from 1996

to 2006, this time as ‘capitalist statesman’..

The two countries we have carried articles on serve as

examples of the distorted development of the colonial revolution addressed in

theoretical terms by Ted Grant in this 1964 document.

The Colonial Revolution and the Sino-Soviet Dispute

By Ted Grant, 1964

The Second

World War ended with a revolutionary wave in Western Europe which, thanks to

the aid of Stalinism and social democracy, capitalism survived. Stalinism in

the Soviet Union, temporarily for a whole historical period, emerged

strengthened.

In the

history of society there have been many methods of class rule. This is

especially true of capitalist society, with many peculiar and variegated forms:

republic, monarchy, fascism, democracy, Bonapartist, centralised and federal,

to give some examples.

In a period

where the revolution (apart from Czechoslovakia) has taken place in backward or

undeveloped countries, distortions, even monstrous distortions in the nature of

the state created by the revolution are inevitable, so long as the most vital

industrialised areas of the world remain under the control of capital.

A decisive

cause of the developments is the Bonapartist counter-revolution in the Soviet

Union. The malignant power of the state and the uncontrolled rule of the

privileged layers in the Soviet Union have served as a model for “socialism” in

these countries. Bourgeois Bonapartism reflects a society in a state of crisis,

where the state raises itself above society and the classes and obtains a

relatively independent role, only in the last analysis directly reflecting the

propertied classes, because of the defence of private property on which it is

based.

The

proletariat is not a “sacred cow” to which analogous processes cannot take

place. Proletarian Bonapartism represents a most peculiar form of workers’

rule. Contradictions in a largely backward society in which the proletariat

represents a small minority, as Lenin pointed out, can lead to the dictatorship

manifesting itself through the rule of one man.

A

proletarian form of Bonapartism by its very nature represents a caricature of

workers’ rule. In a society where private ownership has been abolished and

there is no democracy, the powers of the state gain enormous extension. The

state raises itself above society and becomes a tool of the bureaucracy in its

various forms: military, police, party, “trade union” and managerial. These are

the privileged strata within the society. They are the sole commanding stratum.

In the transition from capitalist society to socialism the form of economy can

only be state ownership of the means of production, with the organisation of

production on the basis of a plan. Only the democratic control of the workers

and peasants can guarantee such a transition. That is why political revolution

in these countries is inevitable before workers’ democracy is instituted as an

indispensable necessity if the state is to “wither away”, but such “transition

regimes” can only be workers’ states—deformed workers’ states—because the

economy of these states is based on nationalisation of the means of production,

the operation of the economy on the basis of a plan.

Marx never

considered the problem of revolution in backward countries as he considered the

revolution would come in the advanced capitalist countries first. These

Bonapartist regimes—regimes of crisis—reflect the unresolved economic and

social problems, both on the narrow national plane and internationally—crises

which can only be resolved by world revolution, especially in the advanced

countries.

The

development of the Chinese revolution, next to the Russian revolution the

“greatest event in human history” as the documents of the Revolutionary

Communist Party proclaimed in advance, took place with a mighty deformed

workers’ state at its back, plus the frustration of the revolutionary tide in

the West. Without the existence of the monstrously deformed workers’ state in

the East, and the paralysing of the hands of imperialism by the radicalisation

of the workers in the West, the Chinese revolution could not have taken the

form which it did.

The Chinese

revolution unfolded as a peasant war (see documents where this is developed)

led by ex-Marxists. Thus as in Eastern Europe the revolution from the beginning

assumed a Bonapartist character, with the classical instruments of Bonapartism,

the peasant army. It was the complete incapacity of the Chinese bourgeoisie to

solve a single one of the tasks of the bourgeois-democratic revolution, which

resulted in the revolution taking the form which it did.

Trotsky in

the pre-war period had posed the problem of what would happen in the case of

the Chinese “Red” Armies emerging victorious in the civil war against Chiang

Kai-Shek. He had tentatively forecast that the tops of the Red Army would

betray their peasant base, and in the cities, with the passivity of the

proletariat, would fuse with the bourgeoisie, leading to a classical capitalist

development.

This did not

take place because on the road of capitalist development there was no way

forward for China. With the model of Russia, the Stalinist leadership of the

peasant armies manoeuvred between the classes, at one time resting on the

“national” bourgeoisie, or the peasants, and at others on the working class and

constructed a strong Stalinist leadership in the image of Moscow. At no time

was there a period of workers’ rule such as in Russia in 1917, when the workers

through their Soviets controlled the state and society.

Just as

bourgeois Bonapartism, manoeuvring between the classes, nevertheless in the

last analysis, defends the basis of capitalist society, so in the same way

proletarian Bonapartism rests in the last analysis on the base created by the

revolution: the nationalised economy.

The Chinese

revolution solved all those problems which bourgeois society was incapable of

solving. The three decades of rule by Chiang Kai-Shek, the Bonapartist

representative of finance capital, revealed the complete incapacity of the

bourgeoisie to unify China, to carry through the agrarian revolution, to

overthrow imperialism. It could only usher in a new period of decay for Chinese

society. It was this which gave the impulse to the leadership of the peasant

armies to overthrow the bourgeoisie and, thanks to the model of Russia at her

back, construct a state on the Stalinist model.

The

leadership was without international or Marxist perspectives. The conscious

role and leadership of the proletariat, without which socialism is impossible,

was absent. The Stalinist leadership, in the conquest of the cities, used the

passivity of the proletariat, and where elements of proletarian action emerged

spontaneously, met these with the execution of the leading participants.

However, the

welding of the atomised and separate provinces into a single unified national

state on modern lines, for the first time in the history of China; the agrarian

revolution; the nationalisation of the means of production: all these gave a

mighty impulse to the development of the productive forces. China advanced as

no colonial economy has advanced for decades.

The Chinese

bureaucracy, like all bureaucracies of a similar character, is interested

mainly in advancing its own power, privileges, income and prestige. It defends

the base of nationalised property on which it rests, because this is the basis

of its income and power.

As predicted

in advance, before the Chinese bureaucracy came to power, the possibility of a

conflict between it and the Russian bureaucracy, was inherent in the situation.

The attempt of the Russian bureaucracy to arrive at an agreement with American

imperialism, without giving consideration to the needs and interests of the

Chinese bureaucracy, precipitated the split between the two tendencies.

The

rationalisation of the split by “ideological” considerations was a means to try

and gain support within the Communist Parties, on a world scale. The Chinese,

for the moment, have used radical slogans as a means of mobilising support in

the Stalinist world movement against the Russians, especially among the

colonial peoples. Their open support of Stalin, repelling the workers in the

Soviet Union and the West, among other calculations, is intended to draw a line

of blood and confusion between the Communist workers looking for a Marxist

solution, and “Trotskyism”, ie genuine Marxism-Leninism.

Because of

their radical slogans, at this time, the Chinese appeal to the cadre elements

in the Stalinist parties looking for a revolutionary road. In that sense, every

nuance, every cranny, must be utilised by the Marxist tendency for the purpose

of finding a way to the sincere Stalinist workers.

The real

face of Chinese Stalinism is revealed in the opportunism of the leadership in

the colonial world, where they have given support to the rotting, feudal,

bourgeois upper strata in many countries. The support of the Imam in the Yemen,

the loans to Afghanistan, to Sri Lanka, to Pakistan, support of Sukarno in

Indonesia, etc. Without being able to compete in resources, they have used the

slender means of the Chinese economy in competition with the Russian

bureaucracy and with imperialism. Their ideology, their conceptions, cannot

rise above the narrow national interests of the Chinese bureaucracy.

Their

“internationalism” consists in trying to build an instrument of support similar

to that possessed by the Russian Stalinist bureaucracy. Their ideology, methods

and attitudes are a counterfeit of Marxism, as much as that of the Russian

bureaucracy, at various stages of its development.

The

idealisation of Stalinism in its crudest and most repressive form, is for the

above-mentioned reason of the need to prevent any tendency of the militant

workers to drift towards “Trotskyism” and because of the nature of the Chinese

economy. Like the Russian before it, such a regime, on the basis of the Chinese

economy alone, may endure for decades, with its slender base in industry, in

comparison with the hundreds of millions of peasants. Only the socialist

revolution in the West, or the political revolution in the Soviet Union, could

alter this perspective.

The

viciousness with which the bureaucracy of the Soviet Union supported India in

the conflict with China, withdrew their technicians and destroyed plans and

blueprints in their endeavours to weaken China, is an indication of the real

character of the bureaucracy in the Soviet Union. They have been ready to

lavish loans and aid on the bourgeoisie and parasitic upper layers of the

colonial countries, in order to prop up these regimes in competition with

imperialism. But to the bureaucracy of another workers’ state coming into

conflict with them, they demonstrated their selfish national aims.

Similarly,

China—as with the diplomatic agreement with Pakistan and the tour of Prime

Minister Chou En Lai, in Africa—apes the Russian bureaucracy in its endeavour

to find friends. In Zanzibar they came to an agreement with the Sultan, before

he was overthrown; they made no criticism of the governments of Tanganyika,

Uganda and Kenya for calling British troops against their own mutinous troops.

The Chinese

Stalinists, not accidentally, advised the Algerians to “go slow” with their

revolution. This was because of the forthcoming diplomatic agreement with

French imperialism. The basic perspectives of Chinese Stalinism are determined

by their national aims of obtaining a seat in the United Nations, and for

strengthening the Chinese national state through whatever means possible,

agreement with imperialism for trade etc. They have attempted to mobilise the

Afro-Asian bloc with this in mind and not at all with the international perspectives

of socialism and the social revolution.

The split

between Russia and China, as with the split between Yugoslavia and Russia and

now the development of new national Stalinism in the countries of Eastern

Europe, Poland, Rumania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, etc., is a symptom of

Stalinist decay and, simultaneously, of the weakness of the revolutionary

forces of Marxism on a world scale at the present time. Had there been in

existence mighty Marxist revolutionary forces of the proletariat, consciously preparing

the revolution in the industrially advanced countries of the world, such a

phenomenon would have been impossible. As at the time of the Hungarian

political revolution of 1956, before which the bureaucracies of these countries

trembled and drew together for mutual protection and support, the Chinese

bureaucracy would not have dared to launch the campaign against Russian

“revisionism”. All these bureaucracies would have been facing collapse and

overthrow.

The split

between the Stalinist bureaucracies on national lines adds further confusion

among the broad masses throughout the world. Even among the advanced workers,

while creating certain opportunities for the ideas of Marxism, it further

complicates the task of revolutionary Marxism. However, in the long term, it

undermines completely the former monolithism of Stalinism and its hold on the

masses. The way is prepared for, on the basis of great events, tens and

hundreds of thousands of workers to enter the revolutionary road. In the next

great upheavals, both East and West, of social and political revolutions,

Stalinism will crumble away.

Nevertheless,

one of the basic tasks of the period is the education of the most conscious

workers not to be infected by any of the variants of Stalinism. There is as

great a gulf between Stalinism in its various forms, both of state and ideology

and real workers’ democracy and Marxism as there is between Bonapartism,

fascism and bourgeois democratic state and ideology.

While

defending the progressive aspects of the economy in Russia, China, Cuba and

Eastern Europe, at the same time it is necessary to draw a fundamental

distinction between the rotten nationalist bureaucratic ideology of Stalinism

and its states, and the conscious control of the economy and of the movement

towards socialism of the working class as explained in the methods and

conceptions of international socialism.

The Colonial Revolution in Asia, Africa and Latin

America

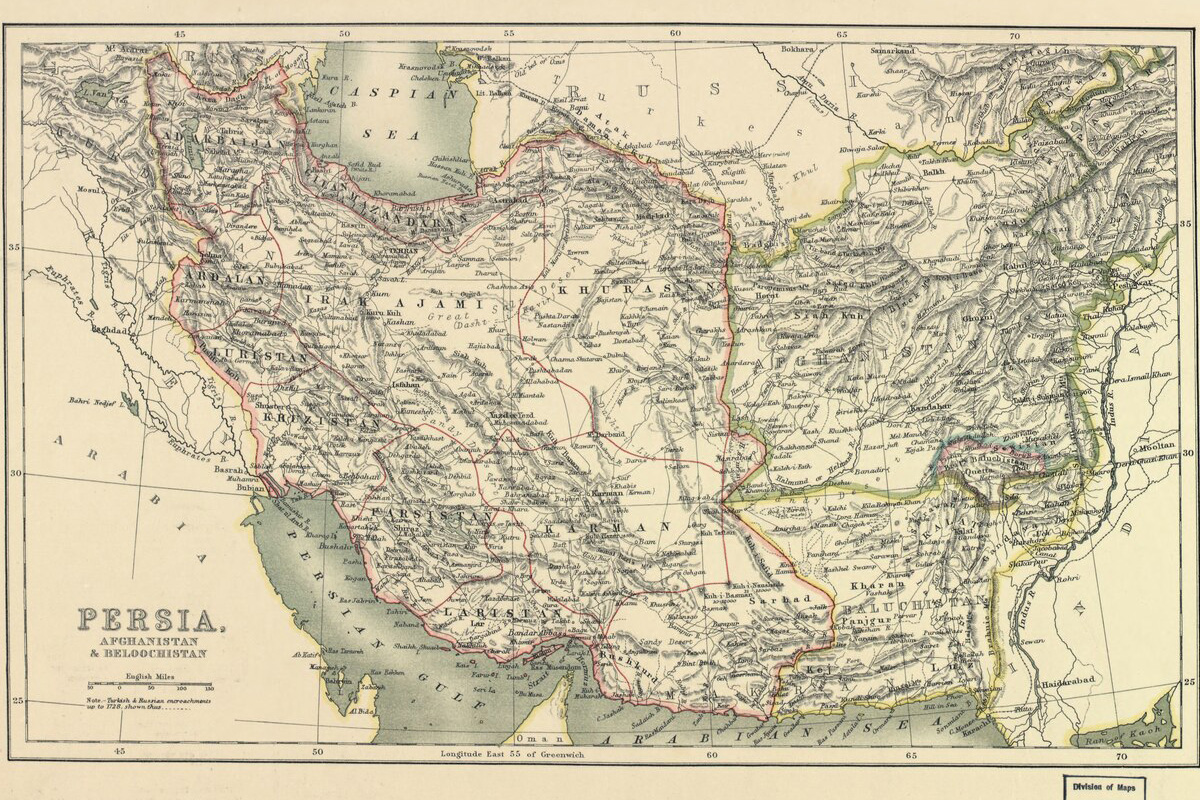

Following

the failure of the post-war revolutionary wave in the West, capitalism succeeded

in stabilising itself for an entire epoch. Consequences became cause. A new

period of capitalist growth was ushered in for all the metropolitan countries,

of greater or lesser strength. The increasing power of the Soviet Union with

its far faster tempo of industrial growth, together with the growth of the

workers’ states and the stabilisation of a mighty China, resulted in a new

balance of forces on a world scale between the capitalist forces of the West

and the workers’ states of the East.

This is the

background on which, in one country after the other, there has been the

continual upheaval of national upsurge and revolution against imperialist

domination and national oppression. At a time of rapid growth of productive

forces in the metropolitan countries the gap between the industrially developed

countries and the so-called “undeveloped” areas of the world has become twice

as great as before the Second World War. The growth of industry on a modest

scale in these latter countries has exacerbated the social contradictions.

In all these

countries, the problems of the national revolution, the agrarian revolution,

the liquidation of feudal and pre-feudal survivals, could not be solved on the

old basis. This has been the period of national awakening of the oppressed

peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Faced with

this upsurge of the colonial masses, the imperialists have been compelled to

retreat. A century ago, Marx explained that only the lack of national

consciousness among the peasant masses allowed the imperialists to conquer and

dominate the East and Africa. Once they were aroused, it was practically

impossible to hold a whole nation in chains. Trotsky in the year prior to the

Second World War, had observed that the task of “pacification” of the colonial

revolts had become far more expensive than the fruits of the exploitation of

the colonies. And this in a period when colonial uprisings were at an early

stage.

Already in

1945, Britain had drawn the conclusion from the revolt of the Indian people, of

the necessity to arrive at some sort of compromise with the Indian bourgeoisie

and landlords. Partly this was due to the impossibility, because of the radical

mood of the soldiers of Allied imperialism and of the working class in Britain,

of waging a large scale war of conquest or re-conquest of India and partly for

fear of the upsurge of the Indian people.

French and

Dutch imperialism had to learn the lessons after the squandering of blood and

treasure in Indonesia, Indo-China, Algeria, etc. The Bourbons(1) of Portugal are in the process of learning

the lesson at the present time.

Thus the lag

of the revolution in Europe and other metropolitan countries has pushed the revolution

to the extremities of the capitalist world, to the weakest links in the chain

of capitalism. However, the development of Stalinism in Russia and its

extension to China and Eastern Europe, the frustration of the revolution in the

industrially decisive areas of the capitalist world, has meant that the

development of the permanent revolution in these underdeveloped countries has

taken a distorted pattern. The degeneration of the Russian revolution, the

Bonapartist form of the Chinese revolution, in spite of its splendours, has

meant in its turn that the revolution in the colonial countries begins with

nationally limited perspectives and with fundamental deformations from the very

beginning.

The

revolution in Russia, which began as a bourgeois-democratic revolution, ended

in a proletarian revolution of the most classic proportions, with the

dominating role of the proletariat as the main decisive force of the

revolution. It culminated in the October insurrection of the working class, which

throughout was based on internationalist and Marxist perspectives. The Chinese

peasant revolt, which culminated in the peasant war of 1944-9, was in a sense

derived from the defeated revolution of 1925-7, but entirely different from it

in the role of the working class. It was a peasant war carried out first

as a guerrilla war, and culminating in the conquest of the cities by the armies

of the peasants.

The

socialist revolution, in contrast with all previous revolutions, requires the

conscious participation and control of the working class. Without it, there can

be no revolution leading to the dictatorship of the proletariat as understood

by Marx and Lenin, nor can there be a transition in the direction of socialism.

A revolution

in which the prime force is the peasantry cannot rise to the height of the

tasks posed by history. The peasantry cannot play an independent role; either

they support the bourgeoisie or the proletariat. Where the proletariat is not

playing a leading part in the revolution, the peasant army, with the impasse of

bourgeois society, can be used, especially with the existence of ready-made

models, for the expropriation of bourgeois society in the Bonapartist

manoeuvring between classes and the construction of a state on the model of

Stalinist Russia.

The bourgeoisie

of the colonial areas has come too late on the world arena to be enabled to

play the progressive role which the Western bourgeoisie played in the

development of capitalist society. They are too weak, their resources are too

narrow to hope to compete with the industrial economies of the capitalist West.

The disparity between the weak and underdeveloped economies of the colonial

world and the metropolitan areas, far from being ameliorated, is gathering

speed. It has been further emphasised during the last two decades by the

upswing of capitalist economy in the metropolitan areas. Whereas in the

capitalist economy in the West, the standard of living of the masses has

increased in absolute terms, even though the rate of exploitation has

increased, there has been an absolute decline in living standards in the East.

By the peculiar dialectic of the revolution, the colonial revolution itself has

actually helped the economies of the metropolitan countries by creating a

market for capital goods.

The imperialists,

except for the Portuguese, were forced to abandon the old method of direct

military domination in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Economic domination

with nominally independent states became the norm.

The [period

since the] Second World War has seen unprecedented upheavals in the colonial

areas. The period of national awakening of all oppressed peoples has been on a

scale and in a measure that military means are doomed to failure, as evidenced

by the British in even such as small island as Cyprus, the French in Algeria,

and tomorrow the collapse of the attempt to pacify Angola.

All these

revolutions and national awakenings have taken place with a lag and delay of

the revolution in the West. However, the greatest force for change in society,

which must always be regarded from an internationalist perspective, still lies

in the decisive areas of Western Europe, Britain, Japan and the United States

in the capitalist world, and Russia and Eastern Europe in the deformed workers’

states. From the point of view of the change from one society to another, while

of fundamental importance to revolutionaries involved in the actual struggle, a

decade or two in the development of society is of secondary significance. The

very growth of the capitalist world, the very development of the economy in the

underdeveloped areas of the world, are all drawing together the threads of

change on a world scale. In the endeavour to compete with the advancing

economies of the Stalinist countries, capitalism has been compelled to use up a

great part of its social reserves. Direct domination and colonial tribute as a

consequence of a military overlordship, have disappeared or are in the process

of disappearing.

Economic

domination and the crushing preponderance of the metropolitan economies over

the frail economies of the colonial or ex-colonial states is even greater and

further increasing than in the past. At the same time, in the metropolitan

countries themselves, the very growth of the productive apparatus has led to a

situation where the social reserves of the ruling class are becoming narrowed.

The growth of monopoly, the growth of industry, the industrialisation of

agriculture, have all led to the contraction of the peasantry and the

petit-bourgeoisie and a further increase in the decisive weight in society of

the proletariat.

From the

point of view of Marxism, no more favourable situation could be envisaged. The

potential power of the proletariat in both the deformed workers’ states on the

one side, and the capitalist countries on the other, has never reached a

greater scope than in the present epoch. From this point of view, a

tremendously optimistic perspective opens out for the future. The tremendous

upsurge of productive forces will inevitably reach its end and result in a new

period of paralysis and decay, such as the inter-war period, in the capitalist

countries. In the Soviet Union and the East, the further development of

productive forces will come increasingly into collision with the stranglehold

of bureaucratic control. The bureaucracy will become more and more incompatible

with the development of society. A new period of social revolution in the West

and of political revolution in the East will be opened out.

It is on

this background and with this perspective constantly in mind that the colonial

revolution in Asia, Africa and Latin America must be regarded. Had Russia been

a healthy workers’ state, or even a state with the relatively mild deformations

of the era of Lenin and Trotsky, then undoubtedly the revolution in all backward

countries would most likely have taken a different form. As Lenin had

optimistically declared with the first wave of revolutionary awakening in the

backward countries of the world, it would have been possible for even tribal

areas of Africa to “go straight to communism” without any intervening period

whatsoever. This could only have been, of course, on the basis of the

integration of the economies of these countries with that of the mightily

developed Soviet Union, on the basis of a genuine and fraternal federation, for

the benefit of all. Of course, in any event, the problem would have been posed

entirely differently; a healthy workers’ state in Russia would have led to the

victory of the revolution in Europe and the industrially advanced countries of

the world, thus posing the problem for undeveloped areas in an entirely

different way. That was the scheme of Marx, who had thought that with the

accomplishment of the revolution in Britain, France and Germany, the rest of

the world (with the crushing industrial preponderance of these areas at the

time) would have been compelled to follow willy nilly.

The

explanation for the way in which the revolution is developing in the colonial

countries lies in the delay and over-ripeness of the revolution in the West, on

the one side, and the deformation of the revolution in Russia and China on the

other side. At the same time, it is impossible to continue on the old lines and

old pattern of social relations. If, from an historical view, the bourgeoisie

has exhausted its social role in the metropolitan capitalist countries, in the

present stage of world society, it is even more incapable of rising to the

tasks posed by history in the colonial areas of the world.

The rotten

bourgeoisie of the East and the nascent bourgeoisie of Africa are quite

incapable of rising to the tasks solved long ago by the bourgeoisie in the

West. Meanwhile the bourgeois-democratic and national revolution in the

colonial areas cannot be stayed. The rise in national consciousness in all

these areas imperatively demands a solution to the tasks posed by the pressure

of the more developed countries of the West.

The decay of

world imperialism and the rise of two mighty Stalinist states, of Russia in

Europe and China in Asia, has resulted in a peculiar balance of world forces.

The bourgeoisie and to a certain extent the national petit-bourgeoisie and

upper layers of colonial society, was allowed a role which would have been

impossible without the world relationship of forces which emerged as a result of

the Second World War. Even the heightened role which the Afro-Asian bloc plays

in the United Nations (albeit on secondary questions—they cannot play the same

role when it comes to a fundamental issue) is an indication of this change. The

competition between the West and Russia—and now China, Russia and the West—for

the aid and support of the ruling circles in Africa and Latin America and Asia,

is an indication of the result of this precarious balance of forces.

The

degeneration of the Russian Revolution and the strengthening of Stalinism for a

whole historical epoch was the main reason why the revolution in China began

right from the start on Bonapartist lines. This in its turn has meant that the

revolution in other countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America had a

ready-made Bonapartist model – which is associated in the minds of the

leading circles of the intellectual strata as “socialism”. Whilst the Chinese

revolution was accomplished largely through a peasant war, and a peasant army

as an instrument of proletarian Bonapartism, at least lip service was given in

the later stages of the revolution, after the conquest of power, to the rule of

the proletariat. This was the case in Cuba also, where the peasant army and the

guerrilla war played the dominant role in the revolution, until the uprising of

the proletariat in Havana. After the transformation of the bourgeois-democratic

revolution under Castro’s leadership into a state on the model of Yugoslavia,

China and Russia, also a dominant role of the proletariat was conceded, but

again in words.

All history

has demonstrated that the peasantry by its very nature as a class, can never

play the dominant role in society. It can support either the proletariat or the

bourgeoisie. Under modern conditions, it can also support the proletarian

Bonapartist leaders or ex-leaders of the proletariat. However, in doing so,

a distortion of the revolution is inevitable. A distortion in one form or

another on the lines of a military-police state.

Every

Marxist who claims to base themselves on the scientific theory of Marx and

Engels, with its deepening and extension in the ideas of Lenin and Trotsky, has

explained the necessary role of the proletariat—and in the role of the

proletariat of socialist consciousness—as the driving force of the changeover

from capitalism into the new society. Without socialist consciousness, there

can be no socialist revolution and no transition of society to socialism.

Marxists like Lenin and Trotsky have not emphasised the role of socialist

consciousness and the conscious participation of the proletariat in the course

of the socialist revolution in the overthrow of the old society for idealist or

sentimental reasons. They did so because without the participation of the

proletariat in the socialist revolution (in the West, the success of such a

revolution is impossible without the mobilisation of all the forces of the

proletariat) and its conscious control and organisation of the transitional

society, a development towards socialism is absolutely impossible.

There is no

automatism of the productive forces without the control [by the workers of the

state]—even in a highly industrialised state like Britain or America, the very

existence of a state would be a capitalist survival from the past. Without conscious

control on the part of the proletariat, whose dictatorship is intended to

speedily dissolve all elements of state coercion into society, the state as

evidenced in Russia and China, inevitably gains an impetus and a movement of

its own.

If in China

the bourgeoisie revealed its utter incapacity to solve a single one of the

tasks of the bourgeois-democratic revolution, events will demonstrate the even

greater incapacity of the Indian, still less of the other Asian and African,

bourgeois elements to solve a single one of the problems posed in front of

these countries by history.

It is the

incapacity of the bourgeois, semi-bourgeois, upper middle class, landlords and

petit-bourgeois to solve these tasks, that poses the problem of the permanent

revolution in a distorted way. Had there been in existence strong Marxist

parties and tendencies in the colonial areas of the world, the problem of power

would have been posed somewhat differently. It would have been posed with an

internationalist perspective. But even then a prolonged isolation could only

have had the same effect as in Russia and China. Even more than in the

industrially developed countries of the West, socialism in one country, or, one

might add, in a series of backward countries, is an impossible chimera.

Nevertheless, the tasks of development in these countries are imperiously

posed. With the world balance of forces, with the delay of the revolution in

the West, with the lack of Marxist parties in these countries and with the

balance of social forces between West and East, between imperialism and these

countries, and with the social classes in these countries themselves, new and

peculiar phenomena are inevitable.

For example,

with a mighty Chinese revolution on its borders, developments in Burma have taken

a peculiar form. Since the end of the War Burmese society has been

disorganised. The national minorities have waged a constant struggle for

self-determination and national autonomy in their own states (Kachins, Shans,

etc.) and at the same time, different factions of the Stalinist party have

waged a terrific guerrilla war. One government has succeeded another, but each

has been incapable of solving the problems of Burmese society. The weak

bourgeoisie has been incapable of putting its stamp on society. Like the

Chinese bourgeoisie before it, it has been incapable of unifying society,

giving it social cohesion and satisfying the land hunger of the peasants, or

breaking the economic power of imperialism. It is a striking symptom of the new

developments in these backward countries that all the factions in Burma claim

to be “socialist”. Imperialism dominated the economy, by its ownership,

largely, of whatever industry existed and [of] the main economic forces such as

teak plantations, oil and transport.

With the

example of China on the border, it became more and more apparent to the upper

layers of the petit-bourgeois that on the road of bourgeois society there was

no way forward for Burma. As in China, in the decades before the revolution,

the bourgeoisie was incapable of bringing the guerrilla war to an end and

ensuring the development of a stable society and the inauguration of

industrialisation and the creation of a modern state.

Each

succeeding government made only the feeblest attempts to try and develop the

economy. The weakness of imperialism, the balance of forces nationally and

internationally, led to a situation where the officer caste posed the problem

before itself of finding some stability within society. In all these countries,

the development of the bourgeois revolution, a bourgeois democratic state, and

a development towards a modern bourgeois democracy, given the existing

relationship of class and national forces and with the pressure of the world

economy, at any rate for any lengthy period is impossible.

Consequently,

some form of Bonapartism, some form of military-police state, was inevitable in

Burma. The army officer caste saw itself in the role of the only strata which

could “save” society from disintegration and collapse, as the feeble bourgeoisie

obviously offered no solution. Consequently, the officer caste which had

participated as one of the “socialist” factions, decided that the only way

forward was on the model of “socialist” China, but called a “Burmese model” of

“socialism”. They have moved rapidly on familiar lines—a one-party totalitarian

state, and the nationalisation of foreign-owned interests, including oil, teak,

transport etc. They have begun the expropriation of the indigenous

bourgeoisie. They even threatened the nationalisation of the small shops. They

based themselves on the peasants and the working class. But they do not have a

model of scientific socialism, on the contrary, their programme is one of

“Burmese-Buddhist socialism”.

Thus we see

the same process at one pace or another in all the colonial countries. At the

moment the process is becoming marked in the Arab countries, which have been in

a state of ferment for the last decade. In Egypt the revolution against the

incompetent and corrupt Farouk(2) regime, agency of imperialism, was led by

the officer caste. Over a period, Nasser has adopted the policy of “Arab

socialism”.

The monotony

with which such tendencies appear in all these countries is striking. Already a

great part of the economy of Egypt is nationalised. The Great Aswan Dam, from

the beginning, was owned by the state. During this year the Nasser regime has

nationalised the greater part of industry. Under the impact of economic crisis

on a world scale, it can be predicted that the ruling caste, with the support

of the workers and peasants, will nationalise the rest of the economy. The

bourgeoisie is so weak and impotent that they are incapable of resistance. The

officer caste which carried out the revolution, with the support and sympathy

of the masses undeniably, did so because there was no perspective of modern

development for the nation under the old system. There were no forces capable

of resisting such change. Imperialism is too weak and has learned the lesson in

the failure of the wars against the national revolutions in the post-war

period. With the model of Russia, China and now a whole series of states, with

the example of developments in Algeria, there is no doubt that the ruling

petit-bourgeois castes (as well as the basis that the Bonapartist regime of

Nasser has among the workers and peasants) will support the complete

nationalisation of the productive forces, stage by stage. Only thus can the

Egyptian state enter into world developments.

It is easy

for this caste to play this role because their [own] privileges and income,

their social role, can be reinforced and increased. The bourgeois system in

these areas is so effete and prematurely decayed that it can offer no perspective

of development.

The most

striking demonstration of the correctness of this thesis are the events in

Iraq. The Communist Party, through its cowardly opportunism and the policy of

Kruschev not to disturb the imperialists in this area, failed to take advantage

of the revolutionary situation provoked by the fall of the old regime. The

impulsion of the masses ended in disappointment and demoralisation.

Nevertheless, the Kassem (3) regime, while waging war on the Kurds, at

the same time was preparing measures of nationalisation.

The recent

counter-revolutionary coup of the army took place to prevent these measures.

But now to maintain themselves in power, and in view of the hopelessness of the

situation, this very caste which is carrying on the reactionary war

against the Kurdish people and which carried out the bloody

counter-revolutionary coup against the temporising regime, has itself now

announced measures of nationalisation, which embrace all important industry and

banks. A great part of these were foreign owned, but nevertheless this coup has

taken place. Like Algeria, for the present, the oil industry has been exempt

from these measures, for fear of reprisals from the powerful international oil

interests. But the tendency is there and will be further reinforced in the next

period.

In Asia the

remorseless peasant war of liberation in Vietnam, which has continued

uninterrupted for 20 years, is nearing success. The American position in South

Vietnam, tomorrow in South Korea, is becoming untenable. The attempt to prop up

the old semi-feudal landlord capitalist state is doomed to failure, especially

with the example of China in the near vicinity. The most far-sighted representatives

of capitalism are well aware of this process. De Gaulle, after his experience

in Algeria, has understood this problem clearly and wishes to take advantage of

it in the national interests of France. They understand that the American war

of oppression is as hopeless as the French stand in Algeria. They see that

landlordism and capitalism in this area are doomed. How to face up to this

problem? There is no question with a peasant war under Stalinist leadership and

with only limited nationalist perspectives of revolutionary contagion of the

West. The area is doomed to be lost in any event. Why not then try and ensure

the victory of a nationalist-Stalinist regime in Vietnam and the rest of

Indo-China, independent of China, like Yugoslavia is independent of Russia?

They want a

Vietnam—once the regrettable and inevitable end of capitalism in the area is

accepted as the perspective—which would look to France and even America for aid

and assistance, in order to prop it up as a force independent of Red China. The

perspective of America in relation to Yugoslavia, Poland and Rumania is their

perspective for South East Asia. Their policy is that of the lesser evil. Why

not make the best of a bad job and make the most of the contradictions of the

national Stalinist regimes? After all, they pose no direct social threat to the

metropolitan areas, no more than Algeria under nationalist leadership did to

France.

In Africa,

Nkrumah(4) in Ghana speaks of “African socialism”.

Under the impact of events it is not excluded that Ghana might take over all

industry. This would be so in the event of economic crisis on a world scale.

A similar

process is taking place in the Algerian revolution. Beginning as a national

revolutionary war against colonial oppression, Algeria finds itself in an

impasse. On the lines of capitalist society, there can be no solution of its

problems. With the result, step by step, that Ben Bella and the FLN (National Liberation

Front) are being pushed in the direction of a “socialist solution”.

Algeria

lacks an industrial proletariat at the present time. The war was waged largely

by the peasant-guerrilla army plus a large stiffening of rural proletarians and

semi-proletarians. Had the leadership of the French proletariat conducted

itself in a revolutionary way, it would have had its effect on the Algerian

struggle but the betrayal of the French Socialist and Communist Parties in

their turn pushed the struggle of the Algerian people through the FLN on to a

purely nationalist basis.

This in turn

led to the situation where the French workers, and technicians in Algeria,

small colons and shopkeepers were pushed into the arms of the fascist OAS

(Secret Army Organisation). The elements in Algeria supporting the Socialist

and Communist Parties deserted to the OAS. This in its turn exacerbated the

conflict. The victory of the revolution led to the fleeing of the French

technicians, artisans and skilled workers to France, creating exceptional

difficulties for the new Algerian state. Right from the start, the control of

Algeria has been on the basis of Bonapartism. If in the early stages, the

elements of a weak workers’ control existed in the enterprises and partially in

the estates expropriated from imperialism, these cannot be of decisive

significance in the future. Without an industrial proletariat and without a

conscious revolutionary party, with half the population unemployed, the regime

will assume a more and more Bonapartist character.

History will

demonstrate whether this will be a proletarian form of Bonapartism or a

bourgeois variant of Bonapartism. The development of events should push the

leadership of the FLN and the army in the direction of establishing the regime

of nationalised property and of state ownership. It can only be, with the

nationalist perspective of the leadership, with the social organisation of

Algeria, with the lack of a conscious proletariat and in the world setting of

the present time, a Stalinist dictatorship of the familiar model—a deformed

workers’ state.

Symptomatic

of the process is the development of the ideology as put forward by Ben

Bella—of Algerian “Muslim” socialism. This Buddhist socialism, African

socialism, Muslim socialism and various other aberrations of a similar

character sum up themselves the process as it has taken place in the backward

countries of the world. The difference between these revolutions and the

proletarian revolutions as conceived by Marx and Lenin, is summed up in the difference

between “Buddhist-Muslim-socialism” and conscious “scientific” socialism. Of

course, every revolutionary worth their salt would hail enthusiastically the

development of the colonial revolution even on bourgeois lines; every blow

against imperialism, every lifting of the chains of national oppression, marks

a step forward in the struggle for socialism and would even be welcomed by all

enlightened elements of society.

Thus in the

last 15 years the development of the colonial revolution in whatever form, is

an enormous step forward for the world proletariat and for the mass of mankind

as a whole. It marks the stepping onto the stage of history of peoples who have

been kept at the level of animal existence by imperialism, an existence hardly

worthy of being called human.

Thus if the

revolutionary working class would hail as a step forward the victory of the

colonial revolution and national independence, even in a bourgeois form, the

defeat of capitalism and landlordism, the destruction of the elements of bourgeois

and landlord society obviously marks an even greater step forward in the

advance of these countries and the advance of mankind.

In the

process of the permanent revolution, the failure of the bourgeoisie to solve

the problems of the capitalist democratic revolution, under the conditions of

capitalist society of modern times, is pushing towards revolutionary victory.

Even the

victory of a Marxist party, with the knowledge and understanding of the process

of deformation and degeneration of Russia, China and other countries, would not

be sufficient to prevent the deformation of the revolution on Stalinist lines,

given the present relationship of world forces.

Revolutionary

victory in backward countries such as Algeria, under present conditions, whilst

constituting a tremendous victory for the world revolution and the world

proletariat, to be enthusiastically supported and aided by the vanguard as well

as by the world proletariat, cannot but be on the lines of a totalitarian

Stalinist state.

Whilst constituting

an enormous step forward from the point of view of ending the stagnation and

restriction of productive forces imposed by imperialism, capitalism and

landlordism and bringing these countries onto the road of a modern

industrialised society, it cannot solve the problems posed in front of these

societies. New contradictions on a higher level will inexorably be posed. The

delay in the revolution in the West has, as a penalty for colonial peoples,

meant that the revolution against imperialism and landlordism, moving forward

to the proletarian revolution, takes place on the basis of Bonapartist

deformation.

It is a

striking indication of the weakness of “Marxist” theorists and their lack of

conscientiousness towards the problems of the socialist revolution, that

nowhere are the problems of the different countries considered from the point

of view of world revolution and world socialism. Even within the ranks of the

“Fourth International”, under the pressure of the great historical regression

in theory and ideas, panaceas are put in the place of Marxist perspective.

Of all [the]

historical tendencies, that of Bolshevism alone began with a clear

internationalist perspective. The Russian revolution was carried through

clearly and consciously as the beginning of revolution in Europe. This

internationalist perspective, an indispensable necessary basis for socialist

revolution, permeated not only the leading cadres but the masses of people led

by the Bolsheviks.

Internationalism

was not conceived as a holiday or sentimental phrase, but as an organic part of

the socialist revolution. Internationalism is a consequence of the unity of the

world economy, which was capitalism’s historical task to develop into a single

economic whole. If Russia, with all her immense resources, and a most

highly-conscious proletariat, with the finest Marxist leadership, could not

solve its problems despite its continental basis and resources, it is ludicrous

for Marxists even to think that in the present world conjuncture it would be

possible in any of these backward countries, in isolation from any healthy workers’

state to maintain anything but a Bonapartist state of a more or less

repressive character.

Internationalism

and conscious leadership—the two go together — are an organic part of Marxism.

Without them, it is impossible to take the necessary steps in the direction of

socialist society. Not one of these states is, in proportion to population,

even as industrially developed as was Russia at the time of the revolution.

Industrial development of a backward economy with the pressure of imperialism

and Soviet and Chinese Bonapartism, the pressure of internal contradictions

which a developing economy would mean, inevitably, in an economy of scarcity,

would lead to the rise of privileged layers.

The

independence of the state from its mass base, which all these countries possess

in common (even where they have had or have the support of the mass of the

population, either enthusiastically or passively), all indicate that on the

basis of backwardness, it is impossible to start the process of dissolution of

the state into society. The necessary dismantlement of the temporary structures

of the state, which would be involved in a society with real democratic control

and participation on the part of the population is in itself an indispensable

prerequisite of a healthy transition to socialism. Thus, the further

development of these states is dependent on the development of the world

revolution.

In those

colonial or ex-colonial countries where the bourgeoisie has been enabled to

maintain a precarious balance for a temporary period, such as India and Sri

Lanka, they have maintained a semblance of bourgeois democracy. In many of the

states in Asia and Latin America, bourgeois democracy in one form or another

has been maintained on the basis of the economic upswing developed since the

war. In India, which had perhaps the strongest bourgeoisie of all the

ex-colonial countries, this regime has succeeded in maintaining itself but the

bourgeoisie in the colonial world has no real perspective.

Thus, on the

onset of the first deep economic crisis, if capitalism maintains itself in

India, bourgeois democracy will be doomed. To maintain itself, the bourgeoisie

will launch on the road of capitalist Bonapartism. The process was clearly

demonstrated in Pakistan(5). In the other countries of Asia and in

practically all the countries of Africa, the upper layers of that society have

only been able to maintain themselves on the basis of a one-party Bonapartist

state—Ghana, Egypt etc.

On a

bourgeois basis, such countries will be condemned to decay and degeneration.

Economically, politically, socially, the bourgeoisie can only develop and aggravate

the problems of society. In India, the bourgeoisie has not solved the problem

of landlordism, the national problem or even the problem of caste. The standard

of living, despite the industrial construction that has taken place, has

actually declined relative to the increase in population. Of all these states,

the Indian bourgeoisie had possibly the best opportunity of taking the road of

the development of a modern economy and a modern state.

Imperialism

with one hand has rendered assistance to India and with the other hand, through

terms of trade and tribute extracted from investments, has undermined the

position of the Indian bourgeoisie. If there has been a certain development in

industry, the exports of such countries have been of light goods such as

textiles, while the imports have been of heavy machinery. With the enormous

development of trade through the division of labour between the metropolitan

countries themselves, the imperialists could allow a certain latitude in the

import of light goods from the colonial countries.

However, the

last couple of decades have been the best economic circumstances under

which these countries could function within the world market, to which they are

bound like Prometheus to the rock, and from which there is no escape. Even in

this most favourable period for capitalism as a whole, the colonial countries’

economics, relative to those of the advanced countries, have suffered an even

greater deterioration than in the period of colonial dependence in the years

before the war. When it will be a question of the mighty imperialist states

looking to find a way to save themselves from the crisis which the economic downswing

will bring, the “concessions” which they give to the colonial countries,

because of fear of revolutions within them, will be terminated in an endeavour

to prevent the mighty social explosions which impend in their own metropolitan

areas. Thus new convulsions and new storms will develop in the metropolitan

areas and certainly in all the colonial countries.

No one,

neither Marx nor Lenin nor Trotsky, could put forward a blueprint for the

development of society. Only the basic and broad perspectives could be

outlined. The failure of the revolution in the West, the degeneration of

Stalinism, the failure of successive waves of the social revolution in Western

Europe, the thwarting of the social revolution in the West and the expansion

and consolidation of Stalinism in the East, have been the world background on

which the revolutionary awakening of the colonial peoples has been taking

place.

In Asia, the

Chinese revolution has imposed its imprint on the development of events.

American imperialism’s endeavours in Vietnam, in South Korea and other areas

adjacent to China, has merely underwritten the rotting social formations of the

past. They have endeavoured to step into the vacuum caused by the expulsion of

Anglo-French and Japanese imperialism from these areas. The military police

states in Vietnam and South Korea and other areas in South East Asia can only

be compared to the rotting regime of Chiang Kai-Shek in the period before the

Second World War.

The weak

bourgeoisie in these countries cannot solve the problems of the bourgeois

democratic revolution. Without the intervention of American troops and money in

Vietnam and South Korea, these regimes would collapse overnight. Even with the

support of American imperialism, the implacable peasant war in South Vietnam,

which has continued uninterrupted since the end of the Second World War, is

undermining the regime and making the victory of the peasant armies, in the

long run, certain. South Vietnam is as much a liability as was Chiang Kai-Shek.

Only the resources of American imperialism permit the throwing of dollars down

a bottomless sink.

In the

immediate post-war period, only the treacherous policy of Stalinism, above all

of the Russian bureaucracy, helped to maintain the precarious balance of forces

in Asia especially in the South East. But the impossibility of finding a road

to the development of modern society in these areas dooms these regimes to the

dustbin of history. Consequently, at any stage, when the pressure of American

imperialism will be relaxed, for whatever reasons, and even in spite of this,

the collapse of all these regimes is certain.

Developments

in Burma, in Laos, in Cambodia [Kampuchea], are all indicative of the way in

which the process will develop. On the road of capitalism there is no way

forward, for all the countries of Asia. In one form or another, there will

be an impulse in the direction of social revolution. In India and Sri

Lanka, particularly the former, with a developed proletariat, it is possible

that the bourgeois democratic revolution could be transformed into the

socialist revolution on the basis of the classical idea of the permanent revolution.

The installation of a workers’ democracy would be its crowning achievement,

once the bourgeois democratic revolution has been accomplished, with the

proletariat, directly through a revolutionary party, leading the struggle for

power.

However, in

these countries, even under the leadership of a Trotskyist party, such as that

of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party(6) in Sri Lanka, the conquest of power by the

proletariat and the firm establishment of a workers’ democracy could only be an

episode, to be followed by deformation or counter-revolution in the Stalinist

form, if it were not followed, in a relatively short historical period, by the

victory of the revolution in the advanced capitalist countries. It would, of

course, even as an “episode” be of enormous historical significance for the

proletariat of the advanced capitalist countries as well as the peoples of the

underdeveloped areas of the world. But even the greatest revolutionary theory

cannot solve the problem without the necessary material base.

It is only

the complete incapacity of outlived capitalism to solve the problems on its

periphery which could allow the conquest of power in these countries. Of

course, with a sub-continent such as India, the victory of the proletariat

would have enormous consequences in Britain and other European countries as

well, if it developed on the lines of China of 1925-7, with the proletariat

playing the decisive part. On the other hand, any development of revolution on

the lines of the Chinese revolution of 1944-9, with the peasantry playing the

decisive role through guerrilla war, would unfold in the same way as the

Chinese revolution of 1944-9.

However, the

development of industry in India, the different traditions of the country, give

the proletariat a preponderant weight in the social life of the country. Given

that Indian Marxists should create a revolutionary party in time, then they

could lead the working class to power, with the aim of creating a workers’

democracy; with the aim of leading the peasantry to the overthrow of the

landlord regime in the countryside; with the aim of unifying the country as a

step towards the international socialist revolution.

Stalinist

China, in its whole outlook, in its methods, in its ideology, [is] not

accidentally saturated with the narrow nationalism of a bureaucratic caste. If,

in the transition from feudalism to capitalism, a whole variety of regimes in

all the kaleidoscopic colours have revealed themselves historically, it is

because in this transition the development of productive forces themselves has

assured a certain autonomism of progress; once the decisive [bourgeois] revolution

had been accomplished in Britain, France and