In 1972, the Conservative government of Ted Health introduced the ‘Fair

Rents Act’ which sought to push up rents for council house residents.

Labour councillors in Clay Cross knew that working class people could

not afford to pay the new rents and voted to refuse to implement the

increases. As a result, the councillors were taken to court, surcharged

and disqualified from office. Their stand became a symbol of resistance

to Tory attacks, attracting solidarity from all over the country. Rob

Sewell talked to one of those councillors involved, John Dunn, about

the struggle and the lessons it has for those fighting the Tory cuts in

2011.

In 1972, the Conservative government of Ted Health introduced the ‘Fair Rents Act’ which sought to push up rents for council house residents. Labour councillors in Clay Cross knew that working class people could not afford to pay the new rents and voted to refuse to implement the increases. As a result, the councillors were taken to court, surcharged and disqualified from office. Their stand became a symbol of resistance to Tory attacks, attracting solidarity from all over the country. Rob Sewell talked to one of those councillors involved, John Dunn, about the struggle and the lessons it has for those fighting the Tory cuts in 2011.

What happened in Clay Cross back in 1972?

It seems ridiculous now, but the whole thing revolved around an increase of 60p on council house rents. The Tory government of Ted Heath had introduced something perversely called the Fair Rents Act, which obliged local councils to jack up rents where it was felt they were too low. In reality this was a crude attack on council housing and the principles that lay behind them of providing affordable housing for all. Clay Cross Urban District Council, as it was called at the time, took a decision – along with a number of other Labour councils, that they would not implement the increases and indeed we never did. As a result, two sets of councillors were surcharged (based on the amount that was deemed to be ‘lost’ by not implementing the increases) and one set were made bankrupt, Two sets of councillors were disqualified from holding elected office and we had a housing commissioner put in, by the government, who’s job it was to now run the housing functions and implement the Act. However, due to the community campaigns, which followed the suspension of the councillors and the affects of the rent strike by local tenants, he was never able to collect an extra penny in rent. This continued until Clay Cross UDC was abolished in 1974 as part of local government reorganisation and made part of North East Derbyshire Council.

At the time Clay Cross was something of a ‘cause-celebre’ in the Labour movement. It became a focal point of the struggle against the Tory government.

Yes, Clay Cross ended up fighting on their own as other councils caved in under pressure but Labour Party conferences passed resolutions in support of our stand, calling on a Labour government to review the disqualification and reinstate us as soon as they were in office. However, the Party leadership made sure that this decision was never carried out. Still, there was fantastic support from around the country. Fighting funds were set up to help pay off the surcharges that had been imposed on us. People toured the country raising funds, presenting our case and always a good response.

Was it true that the Lord Mayor’s chain got melted down to cover the costs incurred?

No, the chain of office was later donated to a Labour history museum. The melting down story is what they call an urban myth – an Urban District Council myth!

What Clay Cross UDC did was recognise that council housing wasn’t just about providing housing in the area but was also about dealing with a social need. We didn’t just not put rents up; we also built new council houses on what was a massive scale. Had this been implemented at the same scale around the country then we would have seen a million new council houses in the UK. We had a fulltime warden scheme to provide support for elderly tenants and we paid those wardens decent wages for the time – a far cry from the scandalous payments made to privatised support staff doing similar work now. Indeed one of the sets of councillors involved got taken to court and surcharged for that as well – apparently it was illegal to pay people a proper wage!

The Clay Cross fight was in many ways an anticipation of the Liverpool fight a decade later.

Yes, there were many similarities. Obviously they were standing up to a Tory government as part of a major city whereas we were just a small local authority with just eleven members and a population of ten thousand – a mining town in Derbyshire. However, like Liverpool, we had a political campaign that ran alongside the physical stand of the councillors. We had public meetings, meetings inside peoples’ houses, street meetings and so on. These were tremendous times. It seemed as though the whole town was involved in one way or another.

John, you were one of the second round of councillors to be taken to court for refusing to implement the Tory Act.

Yes, I can at least say that, hand on heart, I am still the youngest person in the country to be surcharged and disqualified as a councillor – a badge of honour! We took our case through all the levels of the legal system, ending up in the High Court. The first eleven of us had been finally confirmed as surcharged and barred and the Master of the Rolls, Lord Denning, said it was time for the people of Clay Cross to find some just and honest men to take their places – and that it what they got. So I can claim to have been endorsed by Lord Denning no less, although I don’t think he intended us to also make the same stand.

We were only in office for a short period. A surcharge of £2,229 pounds was spread out between us – this may not seem like much but it was just enough to take us over the level at which we would be disqualified automatically. There was no next band of councillors to take our place as the local government reorganisation took place and Clay Cross ceased to exist as a council. The legal fight continued until 1976 when disqualification for a five-year period was confirmed.

At the time you were working as a miner. Did you get a lot of backing from the NUM?

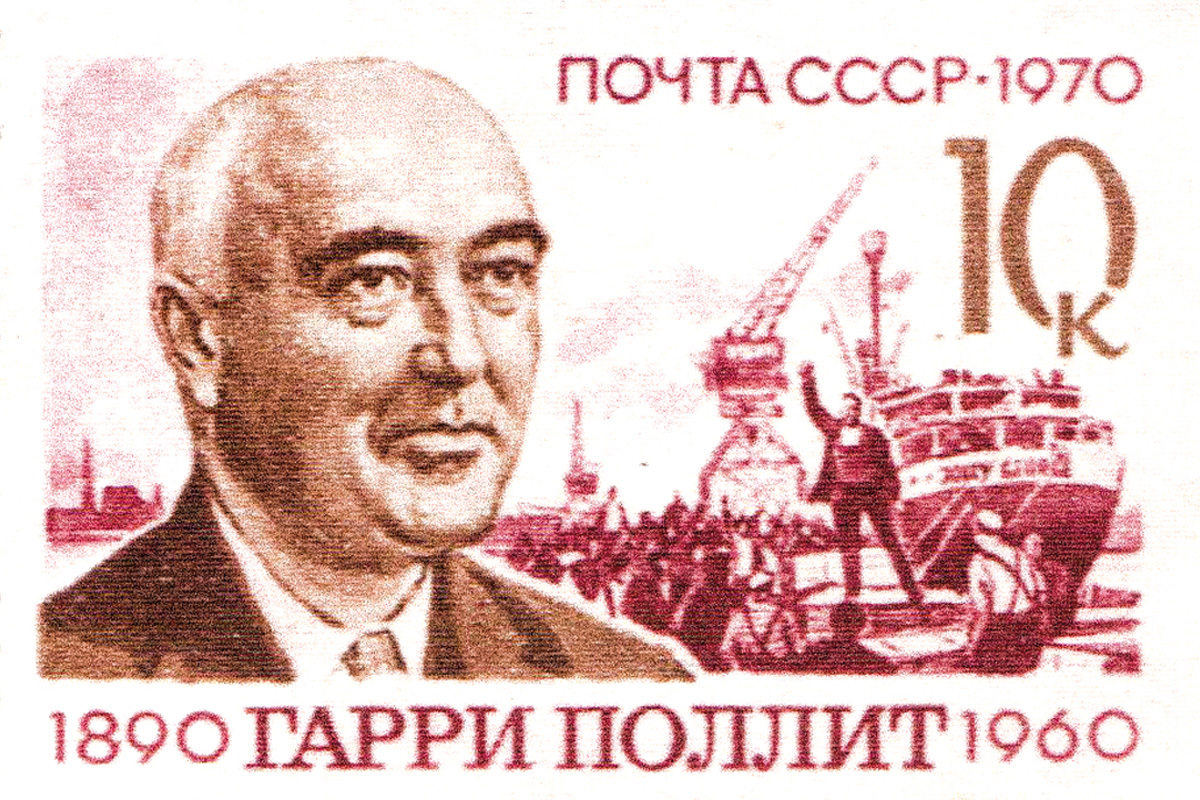

Yes, the NUM made donations and organised meetings at the Pits to get support for our fight. They supported us tremendously, as did many other unions both locally and throughout the country. We spoke at a lot of union conferences and met up with other workers in struggle such as the Upper Clyde shipbuilders, who stick out especially.

What are the key lessons to be learnt from the Clay Cross stand?

The lesson to be learnt for today is that where a council is prepared to stand up and fight and not roll over in the face of Tory bullying (of course, they cannot surcharge anymore), then you can get the support, people will back you. Workers came out and voted for us at record levels as new people came forward to replace those who had been removed.

The bosses pumped huge sums of money into the Ratepayers Alliance with a view to stopping Labour getting elected and supported every Labour renegade they could lay their hands on – people like Dick Taverne – to cut across the Labour vote. They failed. As a result, up to the abolition of Clay Cross UDC not an extra penny in rent was collected from workers’ pockets. This is an example we, in the Labour movement,